Who is Elena Kagan?

She never served as a judge. So how did she get a seat on the highest bench in the land?

Elena Kagan’s heart was pounding as she stood in front of the nine justices of the Supreme Court.

It was March 24, 2009. Earlier that year, Kagan had become the first female US Solicitor General, and this was Kagan’s first time arguing a case in front of the Court. In fact, it was her first time arguing a case in any appellate court at all.

The Solicitor General represents the United States in matters before the Supreme Court, and this case had the potential to be pivotal. She was arguing for a campaign finance law in Citizens United v FEC.

Kagan just couldn’t shake the nerves. She had gone to the movies the night before to try to forget about the case for a few hours, but couldn’t even remember what movie she’d seen.

When she did begin, Kagan got out less than two sentences of her argument before Justice Antonin Scalia leaned over the bench and boomed, “No, no, no, no, no!” She stopped mid-sentence.

Scalia told her that what she just said was wrong.

Surprisingly, this helped. His interruption banished her nerves and she used his line of questioning to lay out her argument. Later, Kagan found out that she lost the case, in which the court decided that corporations are people with free speech rights and that money = speech. It set the stage for unlimited dark money in politics.

Just one year later, Kagan found herself walking back into the Supreme Court. This time, it was to take a seat on the same bench as Scalia.

She had never been a judge. So how did someone with no judicial experience become a Supreme Court justice?

Welcome to our series on the nine Supreme Court Justices. This week is focused on Elena Kagan. Join us each week for another installment.

Law was a part of Kagan’s life from the start — her father was a housing attorney who represented tenants in lawsuits involving their landlords. But Kagan, who was born in 1960 and raised in New York City, didn’t think his job seemed particularly thrilling.

Kagan’s grandparents had immigrated to the states from Russia, and Kagan grew up as the middle of three children in a Jewish household on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. They belonged to Lincoln Square Synagogue, and she was a top student at her Hebrew school.

When she was 12, she wanted to host a bat mitzvah, but at the time, only boys were allowed to observe bar mitzvahs in her synagogue. Other synagogues had started allowing girls to hold ceremonies in the early 1970s, and Kagan decided to fight for her right to do the same.

She ultimately “negotiated with the rabbi and came to a conclusion that satisfied everybody,” according to a friend of Kagan’s. Her service took place on a Friday evening, marking the first formal bat mitzvah at Lincoln Square Synagogue. It was her earliest taste of arguing a case and winning.

Her second winning argument took place in high school, when she lobbied the school president to allow smoking in the girl’s bathroom, so that students (it was an all-girls school at the time) wouldn’t be late for taking a smoke outside. Kagan won again.

One of four bathrooms became a “legal” smoking area, and also, the most popular place to be. With a cigarette in hand, Kagan and friends would exchange fashion tips, talk about schoolwork, and discuss weekend plans.

After high school, Kagan studied history at Princeton and then got her Masters in Philosophy at Oxford University. But then, Kagan felt stuck. It was something she would feel again and again throughout her life. She really wasn’t sure what she wanted to do with her future.

Unlike many of the other Supreme Court justices I’ve written about in this series, like Chief Justice John Roberts or Justice Samuel Alito, she didn’t dream of one day sitting on the Supreme Court. She considered becoming a history professor or a doctor, but neither felt like her calling.

So she applied to Harvard Law School, and got in.

During her first year coursework, Kagan learned that she could use law to impact social change, and after school, her work experience only reinforced this notion. The first was with Judge Abner Mikva on the United States Court of Appeals for the DC circuit.

Mikva, who served as a congressman before becoming a judge, and as White House counsel after, is one of the few people who has served in all three branches of government. To Kagan, Judge Mikva’s varied career represented “the best in public service.”

Kagan said Mikva “had a feel for the way in which government actors worked, how you could expect them to work, what was within the realm of possibility, what you could demand, what you couldn't. And that proved extremely valuable to me in other parts of my career.”

Mikva called Kagan the “pick of the litter” because she was one of the “best and the brightest.”

When her clerkship was over, Kagan was at the next crossroads, asking herself again, “what now?” but this time, Mikva was there with the answer. The first thing he did was recommend her to Justice Thurgood Marshall for a clerkship. Marshall told Mikva, “If she suits you, she’ll suit me.”

By this point, Marshall was in the very late stages of his time on the court, and he was prone to telling stories about his life fighting for civil rights in the South. He’d use facial expressions, throw his voice to imitate different people, and often, clerks were reduced to laughter or tears. Kagan said it was “an education in 20th century history that I will be forever grateful I got.”

She said, “Clerking for Marshall reminded you that you should always be cognizant of not just the intellectual challenge of the law, but the power and ability that the law has to improve or worsen people’s lives.”

Kagan had the utmost respect for Marshall (he, in turn, fondly called her “Shorty”), saying “...at least part of the metric is how much have you done to advance justice? And nobody did more than he did.”

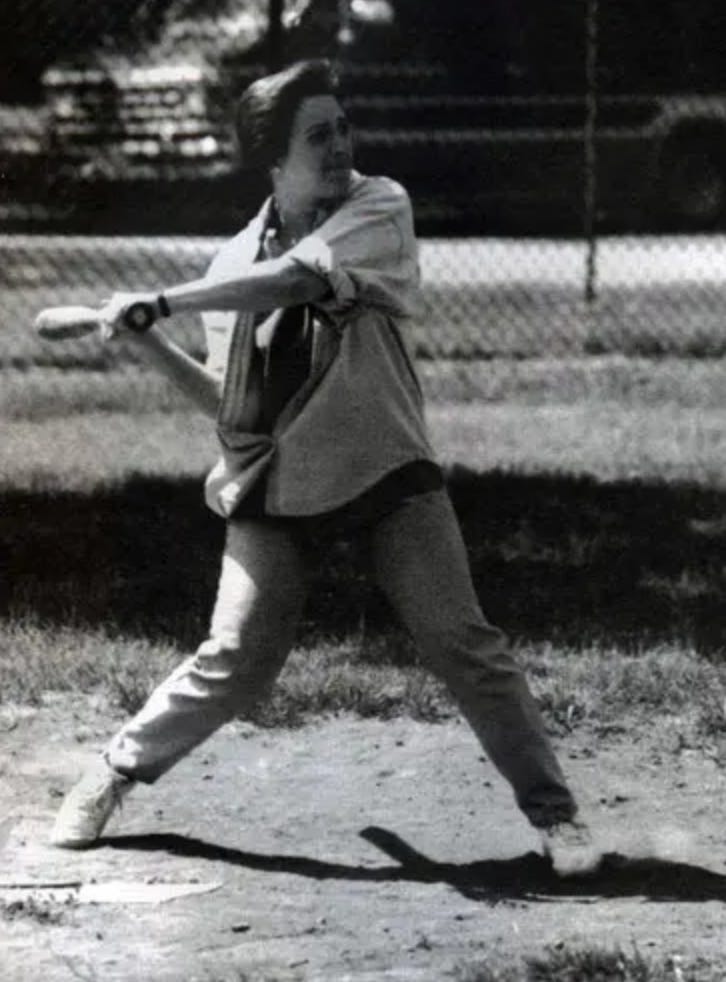

The group of clerks she served with was close knit, and Kagan would join the all-male pickup basketball games in the court’s top-floor gym (it’s jokingly called “the highest court in the land"), despite her short stature. She was a “plucky” guard, who didn’t dominate the court, but was there to be a part of the team.

Kagan learned two things from these clerkships: first, she knew now that she wanted to continue Marshall’s work of advancing justice. And second, from Judge Mikva, she learned that her career did not have to follow a straight line. She could weave her way through government, academia, and law, before settling on what was right for her.

She worked in politics and at a private law firm, but didn’t truly love any of it, so she decided to try teaching, successfully applying for a position at the University of Chicago Law School in 1991.

Kagan enjoyed teaching, and she was often so focused on being a good teacher that she would forget about small life tasks — more than once she parked her car and forgot to turn it off, leaving it running overnight. She was known as a decent poker player, a skill she picked up from regular games while a student at Princeton.

But something was still missing. After Kagan received tenure in 1995, she felt stuck, knowing this wasn’t it for her.

That’s when she turned to Judge Mikva once again. He had left the bench the year before, when President Bill Clinton asked him to serve as White House counsel. Kagan’s interest in government had been sparked by Mikva years before, and she called him to congratulate him. In his telling of the story, Kagan said to him, “You know, I’ve never worked in the White House.”

Mikva didn’t need more of a lead than that. He said, “Would you like to work in the White House?”

The answer was yes. She joined Mikva as a lawyer in the White House Counsel’s office in 1995 and was later offered an opportunity to be a part of the Domestic Policy Council (which researches, creates, and implements the president’s domestic policy ideas).

In both roles, other lawyers frequently sought out her advice, but she rarely offered strong political opinions. She often urged President Bill Clinton to take centrist stances in big battles, including abortion, gun control, family leave, and even smoking (at this point, she was a “reformed teenage smoker who confessed to the occasional cigar”).

White House staffers at the time remember Kagan as someone Clinton frequently pulled aside for hallway conversations. So it wasn’t a surprise when, in 1999, Clinton nominated Kagan to become a judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC circuit. However, the Republican-run Senate blocked the confirmation because they believed she was too liberal, based on her time working in a Democratic White House.

By this point, she had stayed in Washington so long that her tenured spot at the University of Chicago was long gone, and she didn’t get approved by the faculty to return.

She moved on to Harvard in 1999, where she rose to become the first female dean of the law school in 2003. Though she was originally disappointed not to get the job as a judge on the appeals court, Kagan believes that she “learned more things staying in academia and in academic administration than I would have had going onto the D.C. Circuit.”

She had shown signs of being a bridge builder her whole life, but that skill was really honed while dean. Kagan expanded the staff and focused on hiring conservative thinkers in response to criticism that the school was getting too liberal. She also reduced class size to build community. When the faculty would butt heads or was in major dispute, Kagan would offer to host free lunches as a way to get them talking.

Kagan’s work at Harvard, especially with the faculty, was noticed by scholars and legal experts around the nation. It showed that she could be a person who could work with both liberals and conservatives. When Barack Obama became president in 2008, he nominated Kagan to become solicitor general.

Deans from eleven other law schools wrote in support of her nomination and a bipartisan group of eight former solicitor generals endorsed her, among others. She was in the position for a year, arguing before the Supreme Court six times.

From here, she got to see the Supreme Court from a different point of view, and learned the practices and procedures of the Court — including what an “awesome responsibility” and “great privilege” it was to be a justice. She saw firsthand that the court “decides important questions and many people’s lives are changed because of [the] court’s rulings.” That was where she’d be able to really make change through the law.

Her work as solicitor general put her on a short list to take the seat of Justice David Souter when he retired.

But Obama chose Sonia Sotomayor for the position. When Justice John Paul Stevens announced he too was retiring the next year, Obama nominated Kagan. He wasn’t looking for a liberal firebrand (the court already had two of those, Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sotomayor). Instead, he wanted someone who could be a persuasive leader and potentially help appeal to swing voters on the Court.

Obama liked that Kagan had varied experience. He also admired that Kagan believed the law can create change. “That understanding of law, not as an intellectual exercise or words on a page, but as it affects the lives of ordinary people, has animated every step of Elena’s career,” he said.

A justice with no judicial experience hadn’t joined the court in nearly 40 years. Republicans criticized that fact, and didn’t like that she had no paper trail to study (by comparison, Sotomayor had almost 20 years of prior judicial opinions to examine and ask about). They again worried that she would be too liberal based on her time working under Clinton and Obama.

After her nomination, Judge Mikva publicly defended Kagan’s lack of experience as a judge. He said “there ought to be at least one justice, if not more, who understands how real people talk, how the legislative branch makes legislation, how people outside the Beltway talk to each other and how people talk about things other than ancient legal doctrines.”

Democrats controlled the Senate, and Kagan was easily confirmed August 5, 2010, by a vote of 63–37, mostly along party lines. She was sworn in on August 7, 2010.

She quickly hung a portrait of her mentor, Thurgood Marshall, in her office.

Since joining, Kagan has kept a lower profile than some of her colleagues. The justice has voted with the other liberal justices on issues including abortion and affirmative action. But she has continued to try to be a bridge builder on the Court. She went skeet shooting with Antonin Scalia before his death, and traveled with Neil Gorsuch to Ireland. She invited Brett Kavanaugh and his wife over to her house for dinner after he joined the court.

Kagan is also a strict defender of Court precedent (she will vote with a set precedent even if she disagrees with it), such as in the 2020 case Ramos v. Louisiana. She joined Justice Alito’s dissent following the court’s decision to strike down split verdicts (allows conviction without the jury being unanimous). Decisions like this can anger progressives, who see it as boosting conservative viewpoints in the law and beyond.

In 2019, a student at the University of California Berkeley Law School asked if Kagan had thoughts on how people can maintain faith in the court’s fair and impartial administration of justice at a time when the court seems increasingly polarized and votes fall largely on partisan lines.

Kagan responded that the student’s doubts seemed “a little bit overblown to me” and that though the justices disagree, they are “all people who are trying their hardest to do a job, and who should be given the benefit of the doubt that they’re all operating in complete good faith, and who more often than you might think do things that are not expected of them.”

But after the court voted to overturn the federal right to abortion (Kagan dissented in this case), Kagan began to change her tune.

During a speech in 2022 at University of Pennsylvania, Kagan said, “Law should be stable. People depend on law. People rely on law. You give them a legal rule and they order their lives and they order their conduct.”

She continued, “You give people a right and then you take a right away. In the meantime, they have understood their lives in a different kind of way. So, law should be stable. And judges should be humble. It’s a kind of hubris to say we are just throwing that all out because we think we know better.”

In 2023, in response to a question about the declining faith in the court, she said, “You create confidence by acting like a court and by doing something that looks recognizably law-like rather than doing something that looks more political — that looks more like judges are imposing personal preferences.”

Later that year at a different event, Kagan again commented on the court, saying when it “gets involved in things that it doesn’t have to, especially if those things — you know are very contested in a society, it just looks like it is spoiling for trouble, looks like it just wants to decide those matters, even though it doesn’t have to given the case before it. That makes people rightly suspicious.”

Her varied career path, her emphasis on building bridges, and her fierce mind got her on the Supreme Court. With the Court now split six conservatives to three liberal justices, Kagan is using her experience working with conservatives at Harvard to try to build consensus. Whether she’ll be successful in a divided court, only time will tell.

I appreciate Kagan's varied path through politics and academia. It gives me comfort to know that it's ok to have a stable though winding road. I also appreciate that she's a bridge-builder. Seems like we could use more of that spirit around.

You did justice to this justice. Thanks for sharing!