Who is John Roberts?

And when did he change his mind about putting the law above his personal politics?

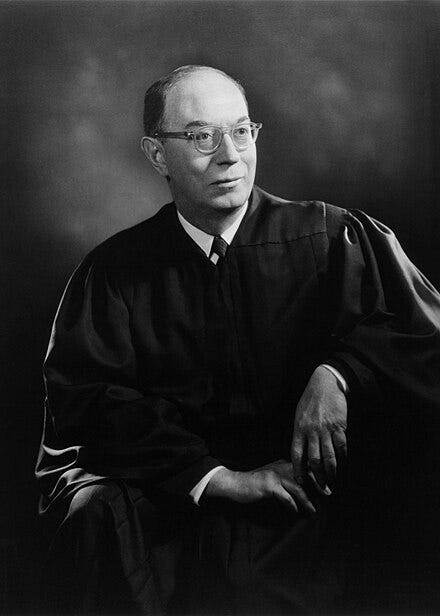

John Roberts went to Harvard Law. And when he finished, he got a job that would change his life: clerking for Henry Friendly, a highly regarded judge who served on the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

Friendly was revered in legal circles as a genius, and many experts tout him as one of the greatest judges of his era. Friendly was a “passionate moderate” as one biographer put it, and he always showcased an “important, strong streak of fairness.” Friendly’s decisions were driven not by ideology, but by an allegiance to administering the law in a rational and predictable fashion.

Friendly’s approach appealed to John Roberts, who believed in consistency and moderation.

While clerking for Friendly, Roberts got a telegram from Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist, who had chosen Roberts for a clerkship. Like Judge Friendly, Rehnquist was politically conservative. But unlike him, Rehnquist was driven by his ideological beliefs to drive the court — and America — towards the right.

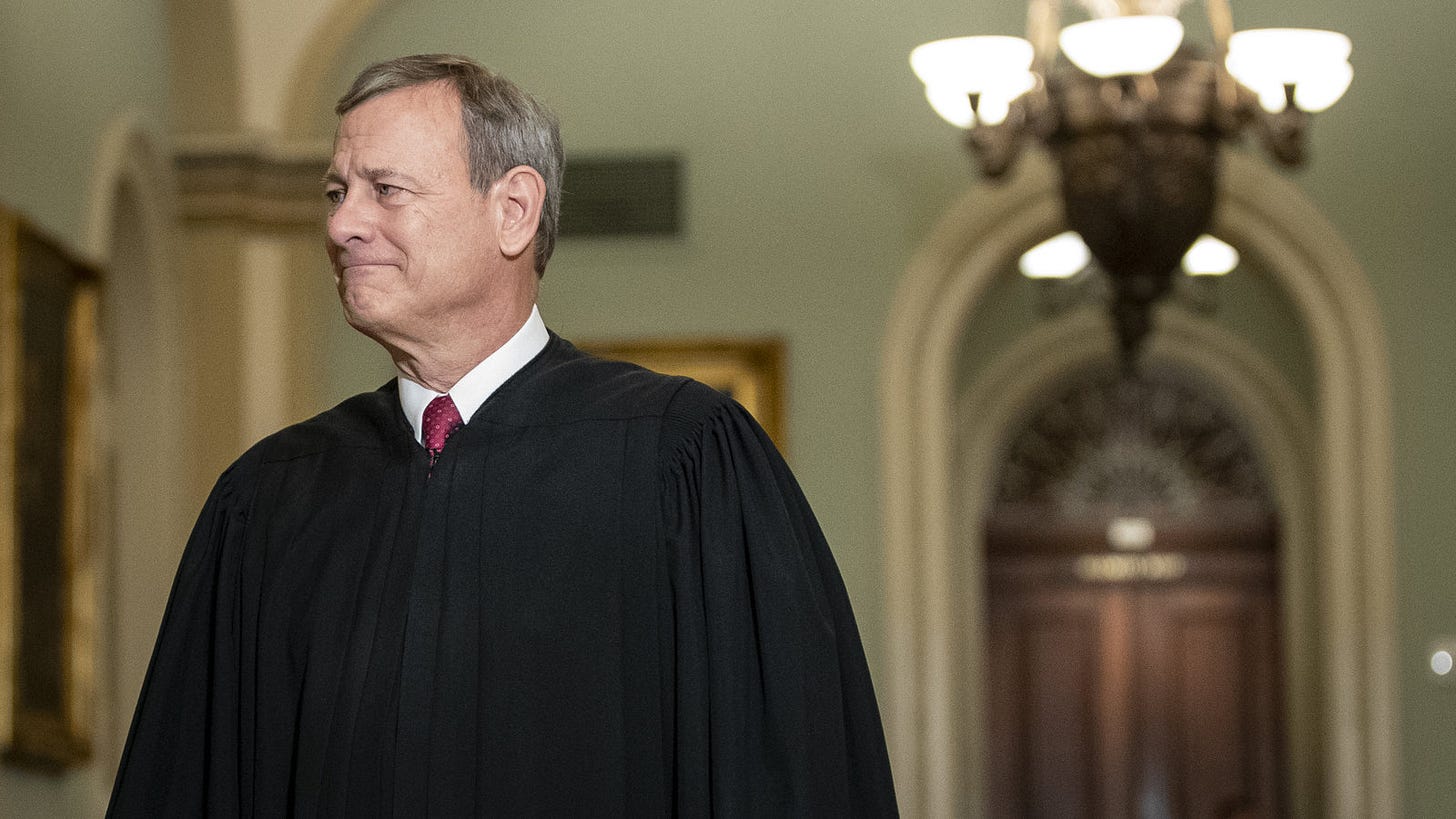

Decades later, Roberts would replace Rehnquist as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. When he started his career on the Court, Roberts modeled himself in the spirit of Judge Friendly. But now, he’s much closer to his predecessor Rehnquist, seemingly bent on driving the Court farther to the right. Roberts himself has penned some of the biggest, and seemingly partisan, opinions of the recent terms.

So what changed?

Welcome to our series on the nine Supreme Court Justices. This week is focused on Chief Justice John Roberts, who is the second-longest serving justice. Join us each week for another installment.

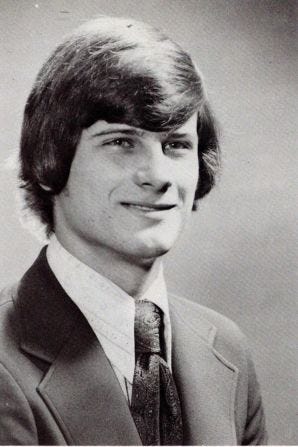

Roberts was born in Buffalo, New York, in 1955. His father was a steel executive, and the family moved to Indiana in the early 1960s. Roberts grew up on a quiet, tree-lined street in an upper-class, mostly white neighborhood.

Jackie, as he was called as a child, was an overachiever from the beginning. He got straight A’s from a young age, always had his head in his books, and at 13 said he would only be content in life if he got “the best job by getting the best education.”

Roberts attended Catholic boarding school for high school, where he was captain of the football team (even though he wasn’t a very good player), on the track and wrestling teams, part of student council, and even participated in theater productions.

Ken Starr, a prominent figure in Roberts’ early career, said of him, “I think his deeply Catholic upbringing and his going to an intellectually stimulating high school are at the roots of his character. He was able at that high school to be Mr. Everything.”

Roberts was known for his sense of humor and quick wit, and he found camaraderie with other Rehnquist clerks. They often played basketball on the Supreme Court court, and more than one person ended up in a cast.

Rehnquist himself was known for his practical jokes and would also involve his clerks in wagering on anything from football games to the length of the president’s State of the Union address. Roberts wrote to Friendly not long after starting with Rehnquist, saying the judge is “at once amiable and challenging and very open with me and my two co-clerks.”

In 1981, Roberts listened to Ronald Reagan’s inaugural address, and felt like Reagan was speaking directly to him. When Reagan said that he did not believe in a “fate that will fall on us no matter what we do,” but instead, “in a fate that will fall on us if we do nothing,” Roberts heard this as a call to action.

Roberts said this speech helped him realize that there was a cost to inaction, and as Supreme Court biographer Joan Biskupic writes, “it was time for Roberts to join the ideological battle.”

After Reagan became president, Rehnquist wrote a letter to Kenneth Starr, who was counselor to Attorney General William French Smith, recommending Roberts for a position in the Reagan administration.

It was during his early years in government that Roberts began to shed his moderate exterior. He wrote memos to superiors, arguing that they should “challenge not only the status quo, but also fellow Republican officials who were… not sufficiently committed to the Reagan agenda.” He solidified his view on many issues during this time, including affirmative action, voting rights, and abortion.

After leaving the White House in 1986, Roberts worked in private practice and experienced what it meant to be on the other side of the bench as a lawyer arguing a case before the Court. His former boss, William Rehnquist, presided over the hearing as Chief Justice. Roberts went on to hold other positions in government, building his resume and catching the eye of people above him.

In 2005, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor announced she was retiring, and George W. Bush began to consider choosing John Roberts to replace her.

Bush’s aides told him it was a mistake. They said he should look for someone with more experience, someone older. President Bush didn’t heed their advice. In his memoir, Bush wrote Roberts was “a genuine man with a gentle soul … his command of the law was obvious, as was his character.”

He nominated Roberts to O’Connor’s seat in July of 2005. But before Roberts could be confirmed, William Rehnquist died after a short battle with cancer. Bush decided to nominate Roberts to fill his former mentor’s role.

The senate voted 78-22 to confirm Roberts on Sept. 29, 2005, making him just the 17th chief justice in US history. During his confirmation hearing, Roberts laid out his plan as Chief, saying, “Judges are like umpires. Umpires don’t make the rules, they apply them… They make sure everybody plays by the rules, but it is a limited role. Nobody ever went to a ball game to see the umpire.”

And though he did act like an umpire in some cases, he also followed in Rehnquist’s footsteps by furthering his own conservative goals on the court. Two of his court’s most well-known decisions changed how we run elections. One made it easier for wealthy donors and corporations to influence elections and the other limited the reach of the Voting Rights Act, a long-held goal of Roberts.

But for years, Roberts was seen as a swing vote, someone who would try to work with the liberal justices and put aside his own beliefs in place of his commitment to the court precedent.

For example, in 2012, he overruled challenges to the Affordable Care Act, despite massive backlash from conservatives and even some of his fellow members on the court.

During his first decade on the court, he rarely made decisions that would create sweeping overhauls of the current system. Roberts wanted the public to view the Supreme Court favorably and have faith in the Supreme Court as an institution.

Then, President Donald Trump nominated three justices to the court. Those justices were younger and more conservative than Roberts. Roberts found himself on a court that was more partisan and was losing the trust of the public. The nation was more polarized, the court more divided, and compromise seemed impossible.

So Roberts stopped trying to compromise. Instead of making small, incremental changes like he tried in the past, Roberts has penned majority opinions on cases that have completely tossed out decades worth of precedent. Roberts, who previously tried to avoid partisanship, is leaning into it.

At the end of the term, Steve Vladeck, a professor at Georgetown University Law Center, said: “We saw Roberts—who for much of the first 15 years of his time on the court was conservative but not crazy—actually trying to keep the court together, at least to some degree… And I’m struck this term by how much he just didn’t care.”

Years ago, Roberts said that when justices put on their robes, their political affiliation is gone. What is left is an “extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their best to do equal right to those appearing before them.”

Roberts has always been concerned with his legacy as chief justice. Will he continue down the path of partisanship, or will he try to steer the Court towards his long-held belief that the Court should not consider personal politics in their decision making? We’ll find out in October, when the court is back in session.

I’d love to hear your thoughts and answer as many questions as I can in the comments below!

i went to law school and while i didn't ever end up practicing law, constitutional law was my favorite class. it felt most rooted in concepts that i already understood. i greatly respected my professor who said something like, "i'm not here to get you to think like me, agree with me, or agree with the decisions. i'm here to help you to understand why the court decided the way they did, and to understand the dissent, too, even though it's not law."

we were called on randomly via the socratic method, and the young woman called on for roe v. wade said something like, "oh, no. i'm not the right person to talk about this because i think it's wrong." our professor answered, "that's why you're exactly the right person to answer this."

i share his philosophy as background for why i emailed him a few days after the 2016 election and asked for his thoughts. one thing he said was, "Second, there is some hope that Justice Roberts understands that if the Court becomes a rubber stamp for right wing ideologues, it will be discredited as a principled institution."

i've kept that in my mind all these years, and especially over the last few years as roberts has changed his approach.

I am so disappointed that members of the Supreme court have become so corrupt, taking bribes, flying upside down flags and displaying so much partisanship in their rulings. This last term was a disaster. Giving a President absolute immunity is a terrifying ruling and goes against the intent of the Constitution. If there weren’t many, many other reasons for me to vote against Donald Trump, the possibility that he could appoint two more Supreme Court Justices would be reason enough for me to vote against him.