Who is Samuel Alito?

The child of teachers, the justice now socializes with billionaires

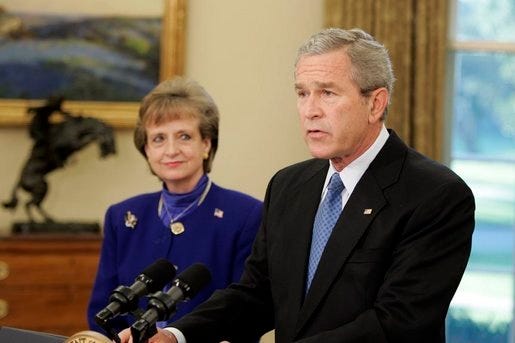

Samuel Alito was not George W. Bush’s first choice for a Supreme Court justice.

When Sandra Day O’Connor announced she was retiring on July 1, 2005, Bush nominated Harriet Miers to replace the court’s first female justice.

Miers was an interesting choice. She served as Bush’s personal attorney when he was governor of Texas, and she wrote him praise-filled notes, saying things like, "You are the best governor ever — deserving of great respect."

Miers was brought into the White House after Bush was elected president, first working as the White House staff secretary before being promoted to deputy chief of staff. She eventually became White House counsel, and from there, Supreme Court nominee.

The choice was highly scrutinized. Some of the headlines of the time read: “Bush's New Supreme Court Pick: A Loyal Aide With Scanty Record” (The Wall Street Journal), Bush Nominates Insider to Supreme Court” (NPR), “Bush Supreme Pick Stuns GOP – Taps Pal Who’s Never Been Judge” (The New York Post).

Anti-abortion conservatives adamantly fought against the choice, complaining that Miers had no proven track record of opposing abortion. Others took issue with the fact that Miers had no experience with constitutional law.

Bush said that he picked Miers because she was “the best person he could find” and that she has “devoted her life to the rule of law and the cause of justice,” and that she would "not legislate from the bench."

Ultimately, after weeks of widespread criticism, she withdrew herself from consideration.

Bush then nominated Samuel Alito, who was a conservative judge serving on the Third Circuit Court of Appeals.

Bush liked that Alito was “scholarly, fair-minded and principled” and said Alito’s record “reveals a thoughtful judge who considers the legal merits carefully and applies the law in a principled fashion…He understands judges are to interpret the laws, not to impose their preferences or priorities on the people.”

Alito is now one of the most conservative members of the court. So how did the son of schoolteachers from New Jersey become a man who befriends billionaires and makes headlines for the flags he flies at his homes?

Welcome to our series on the nine Supreme Court Justices. This week is focused on Samuel Alito. Join us each week for another installment.

Samuel Alito was born in 1950 in New Jersey to Italian immigrants who both worked as teachers.

Alito went to public school, where (like many other future Supreme Court justices) he was an overachiever, participating in more than ten clubs and activities, including the debate team, band, track, the honor society, and student council. When he ran for student council, Alito made posters that showed women getting their hair colored and the slogan: "I'll just DYE if Sam isn't elected. Alito for President."

Alito remembers that any time he had a paper due at school, his father would insist they read it together. “We would sit down at the kitchen table and we would go over it word by word, sentence by sentence,” Alito said. “He would ask, ‘Why did you say this? Wouldn’t it be better to put it this way?’ and ‘Is this necessary?’ It was a very painful process that I would have spared myself if I had had the option at the time, but very valuable in retrospect.”

When Alito was young, his father stopped teaching and became the first director of the New Jersey Office of Legislative Services, a nonpartisan office that helps draft laws.

One of his tasks as director was to redraw New Jersey’s voting district to better represent the residents. Alito remembers hearing his father typing away on a manual calculator late into the night, doing the math to create districts with equal populations. Alito credits his father’s dedication to the legislature as one reason he became interested in law from a young age.

Young Sam loved being on the debate team in high school, and that’s where he really first started thinking about the constitution. The team would have to research and debate legal rules and procedures using constitutional law as a reference, and this piqued his interest – how was the Constitution fairly applied?

After graduating from high school (where he was valedictorian) in 1968, he attended Princeton, where he said he developed a “deep interest in constitutional law, motivated in large part by disagreement with Warren Court decisions.” At the time, the Supreme Court was led by Chief Justice Earl Warren – the former governor of California who oversaw landmark decisions like Brown v Board of Education, Miranda v Arizona, and Gideon v Wainwright.

At Princeton, Alito stood out as a rare conservative during a time of liberal uprising. Friends remember him as an “unflappable outsider,”and a student protest over the war in Vietnam in the spring of 1970 particularly bothered him. He was a sophomore at the time, and on the last day of classes, students boycotted. Faculty agreed to waive exams and other end-of-term activities.

Alito was annoyed. One of his classmates said Sam was miffed that he wasn’t allowed to take his exams. He didn’t like that the protestors essentially shut the school down while others had no say in it.

Princeton is also where Alito had his first experience with the Supreme Court when his debate team traveled to Washington, DC, and he had the opportunity to meet his Constitutional law hero: Justice John Marshall Harlan II.

Now, you have to remember that Alito had been watching the Warren Court for years, and that his disagreement with the court’s rulings was a big reason he started studying the law. And Harlan, who was known as the court’s “great dissenter” also disagreed with these rulings, and for that, Alito greatly admired him.

We don’t know exactly how Alito felt walking in to meet one of the people he admired most, but we can imagine. The trip from New Jersey to Washington, DC isn’t long, but the few hours likely provided enough time for Alito to go over the questions he had for the justice a couple of times. Alito was one year out from graduating, and was already planning to come back to the court, whether as a lawyer or a judge. When he walked into the Supreme Court in his early 20s, he could feel the future unspooling before him.

When they met, Justice Harlan responded enthusiastically to Alito’s questions, emphasizing that “the duty of the judge to decide the case at hand, not promulgate new rules of conduct for society as a whole.” Harlan was underscoring what Alito already felt about the Supreme Court: it should not be a source of activist reforms.

That meeting laid the foundation for who Alito would later become as a justice.

The trip also seemed to solidify Alito’s goals. The next year, his senior yearbook entry at Princeton reads, “Sam intends to go to law school and eventually to warm a seat on the Supreme Court.”

In 1985, Alito was hired as deputy assistant attorney general for the Reagan administration. In his application, he wrote that he believed in “the legitimacy of a government role in protecting traditional values,” and that he was “particularly proud” of contributing to cases arguing that "the Constitution does not protect a right to an abortion."

In 1990, Alito got his first seat on the bench when George HW Bush nominated him to the US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. He remained there for 15 years.

When O’Connor announced her retirement, Alito’s name was added to Bush’s short list of replacements, but Bush ultimately chose John Roberts. (See our profile of Roberts here.)

But a few months later, Chief Justice William Rehnquist died, and Bush quickly decided to nominate Roberts for the chief justice position instead, leaving an open Associate Justice position. Both George W. and his wife Laura felt that spot should be filled by a woman. But Bush kept running into “frustrating roadblocks” with all the female candidates his team was bringing him. One top contender was federal appeals court Judge Priscilla Owen, but her nomination to the appeals court had been contentious, and Bush was worried that would happen again.

And that’s when he turned his attention to Miers, who was helping the search committee put together a list of candidates. After Miers withdrew, Bush chose Alito, because he did not feel there were any qualified women that had a more conservative viewpoint.

A White House spokesperson at the time said Alito’s 15 years as a judge shows “a clear pattern of modesty, respect for precedent and judicial restraint.”

But Alito’s confirmation was not smooth. In fact, it was so intense that at one point his wife was reduced to tears.

Democrats were opposed to Alito based on his openly conservative views, and pressed him during the hearing on whether he would be able to put aside his personal feelings on abortion as a justice.

At one point, Sen. Ted Kennedy tried to connect Alito to an article written by a member of a group Alito formerly belonged to, the Concerned Alumni of Princeton (CAP). Alito had listed that he was a member of CAP on his 1985 job application to join the Reagan administration. The article in question was full of racist and anti-feminist language, and Kennedy wanted to know if Alito agreed.

With a raised voice, Kennedy asked if Alito shared the belief that the Black and Latino communities “just don’t seem to know their place.” Alito responded, “I disagree with all of that. I would never endorse it. I never have endorsed it.” He said that he did not recollect being a member at all but that “had I thought that that’s what this organization stood for, I would never associate myself with it in any way.”

In defense of Alito, Sen. Lindsey Graham asked him, “Are you a closeted bigot?” Alito said no, and Graham responded, “No sir, you are not.”

As the disagreement played out in front of her, Alito’s wife, Martha-Ann, broke down into tears and quickly left the room. Alito’s sister, Rosemary, put her arm around Martha-Ann and walked out with her. And though his wife cried, NPR wrote at the time that Alito “never once showed any emotion. His voice remained flat, even monotonous.” He consistently said that he would have to know the specifics of a case before making a decision, and that he would be impartial if confirmed. At one point, he said, “If I’m confirmed, I will be myself.”

In total, Alito spent 18 hours testifying before Congress over the course of three days.

He was confirmed 58-42, with nearly all of the Democrats opposing his nomination.

Bush hosted Alito at the White House after Alito’s swearing in, and told him, "Sam, you ought to thank Harriet Miers for making this possible."

Since joining the court, Neil S. Siegel, a professor at Duke Law School, says that Alito has become the “most important conservative voice on the Court.” Siegel writes that Alito “voices the concerns of Americans who hold traditionalist conservative beliefs about speech, religion, guns, crime, race, gender, sexuality, and the family.”

Now, how did Alito make it on Bush’s shortlist at all? It is the same way he made friends with billionaires.

Both of those answers come back to the Federalist Society and a man named Leonard Leo. The Federalist Society, created in 1982, promotes conservative readings of the constitution. Leo was a founder of the Federalist Society, and Alito is a member.

Leo is a conservative lawyer who met Judge Clarence Thomas in Washington, DC in 1990 while clerking for the US Court of Appeals. From the Court of Appeals, Leo became a researcher on the White House team working on Thomas’s nomination to the Supreme Court. Thomas was confirmed (see our profile of Thomas here), and Leo was thrilled. He decided to make it his life goal to help get conservative judges placed around the country, including on the Supreme Court.

To get someone on the Supreme Court, you have to convince the president to nominate them, and then convince the Senate to confirm them. This is what Leo spent his time doing. When Bush became president, the White House began to see Leo as an ally, someone who could help Bush find conservative judges to nominate to the federal judiciary.

Around 2005, Leo also helped start the Judicial Confirmation Network (JCN), a fundraising organization. Their goal? Make sure that the federal judiciary reflects a conservative view. When Harriet Miers withdrew from consideration, the Judicial Confirmation Network took out radio and online ads in support of Alito’s confirmation.

Since Alito joined the court, he and Leo have remained close. And Leo has built up connections with wealthy donors and conservatives, who he has introduced to Alito.

Take, for example, Paul Singer, a hedge fund billionaire. In 2023, ProPublica reported that Alito took an unreported fishing vacation in 2008 that was organized by Leo. Leo personally asked Singer if Alito could take Singer’s private jet to Alaska — if Alito had paid for this himself, it would have cost at least $100,000 for just one way.

Supreme Court Justices (and all federal judges) have to fill out financial disclosure reports every year, where they list any gifts they received. Alito did not disclose this trip.

After the trip, the hedge fund Singer owns appeared before the court at least 10 times. Alito never recused himself from those cases. In one case in 2014, the Supreme Court ruled in the hedge fund’s favor, 7-1 during a battle between the hedge fund and the nation of Argentina. Because of the ruling, the hedge fund received $2.4 billion.

And while Alito is seen by some as a beloved and dependable conservative member of the court, he has also faced controversy outside of his relationship with Singer and Leo, including other times where he has refused to recuse himself from cases.

This year, it was reported that two separate flags that have become symbols for Trump supporters were seen flown outside Alito’s home and vacation house in 2021. Alito said that his wife was responsible for hanging the flags. This is an issue because Supreme Court justices are supposed to be nonpartisan, and not show any public political leanings. Because both flags have become signs for Trump supporters, many quickly assumed that Alito supported Trump.

After the news came out, Alito did not recuse himself from the recent case on presidential immunity. Ultimately, Alito voted with the majority, 6-3, to grant presidents, and Trump, full immunity for official actions taken in office.

Alito made headlines again this past June when Lauren Windsor, a filmmaker, attended the annual gala for the Supreme Court Historical Society. While there, she approached several justices as though, according to her, she was a “religious conservative” and secretly recorded their conversations. She later released the audio.

When she spoke to Alito, she said, “I don’t know that we can negotiate with the left in the way that needs to happen for the polarization to end. I think that it’s a matter of, like, winning.”

Alito responds, “I think you’re probably right…one side or the other is going to win. I don’t know. I mean, there can be a way of working — a way of living together peacefully, but it’s difficult, you know, because there are differences on fundamental things that really can’t be compromised…So it’s not like you are going to split the difference.”

Windsor then tells Alito, “People in this country who believe in God have got to keep fighting for that — to return our country to a place of godliness.”

The justice says, “I agree with you.”

These comments sparked concerns among Alito critics that he cannot be neutral when he feels so strongly about being unable to work with the other side, and that one side must win. Critics said these comments are proof that Alito allows his personal attitudes to affect his rulings — especially in terms of religion.

With Alito on the bench, the Supreme Court has narrowed the gap between church and state, including ruling that school vouchers (tax dollars that go to school tuition) can be used at religious schools.

Ultimately, to truly understand Samuel Alito as a Supreme Court justice, you don’t have to look further than what he said on his 1985 application for deputy assistant attorney general: He believes in traditional values. And he has held true to the promise he made during his confirmation hearing: Once on the court, he has been himself, a judge who supports legal decisions that uphold what he views as traditional values.

These are just so good. The amount of research you do to pull these together - on judges, on bookclub deep dives, on TSATM characters, on daily news updates, on podcasts - is utterly incomprehensible to us mere mortals, let alone the work that goes into weaving research into a digestible story. In case you haven't been told in the past few minutes, *thank you* for doing what you do.

Well, if the originalist idea they were hoping to uphold was that only white, landed, wealthy men would have rights in this country, I think they’re getting pretty close to that.

How convenient that they never see the constitution as the living breathing document that the founders actually intended.

Regardless, I would love to live in a country that doesn’t look to enslavers from a bygone era about how to handle issues affecting 300 million plus people. And when I hear “this issue will be handled by the states”, I just hear “some people in some states should have rights and other people in other states shouldn’t”