Who is Brett Kavanaugh?

He oversaw some of the biggest scandals in DC, until he became the focus of one

Brett Kavanaugh had questions for Bill Clinton, and some of them were graphic.

It was 1998, and then-President Clinton was set to testify to a grand jury about his relationship with his 22-year-old intern, Monica Lewinsky. Kavanaugh was working as an associate for independent counsel Kennth Starr, who was investigating Clinton. And Kavanaugh believed their team had a responsibility to “make [Clinton’s] pattern of revolting behavior clear — piece by painful piece.”

That meant asking some explicit questions about Clinton and Lewinsky’s sexual history. In a memo dated August 15, 1998, Kavanaugh wrote that the “President has disgraced his Office, the legal system, and the American people” with his “callous and disgusting behavior.”

Clinton, Kavanaugh believed, “should be forced to account for all of that and to defend his actions.” Kavanaugh saw no world where Starr’s office should go easy while questioning the president. He asked, “Aren’t we failing to fulfill our duty to the American people if we willingly ‘conspire’ with the President in an effort to conceal the true nature of his acts?”

Kavanaugh’s questions to Clinton were pointed and graphic, and I won’t detail them here. But if you want to know how specific, here’s a link.

Kavanaugh went on to author much of Starr’s final report on the affair, which included sexually explicit descriptions of the relationship. But before it went to Congress, he had a slight change of heart, telling Starr he objected to publishing the intimate details, saying, “our job is not to get Clinton out. It is just to give information.” Ultimately, the entire report was released, details and all.

But that change of heart stuck. In 2009, Kavanaugh wrote in an article that sitting presidents shouldn’t be investigated, questioned, or involved in civil or criminal lawsuits because it distracts from the job.

Kavanaugh said, “Even the lesser burdens of a criminal investigation— including preparing for questioning by criminal investigators— are time-consuming and distracting. Like civil suits, criminal investigations take the President’s focus away from his or her responsibilities to the people. And a President who is concerned about an ongoing criminal investigation is almost inevitably going to do a worse job as President.”

Nearly two decades later, Kavanaugh found himself back in front of the Senate discussing sexual assault allegations – but this time, they were levied against him after he was nominated as a justice to the Supreme Court. After emotional testimony, Kavanaugh was confirmed. And once on the bench, he played a role in granting the presidency full immunity for official actions.

Before joining the court, Kavanaugh was a part of some of the biggest investigations in DC scandals and dramatic Congressional showdowns. How did this help his trajectory to the court, and how did it shape the way he’s ruled since then?

Welcome to our series on the nine Supreme Court Justices. This week is focused on Brett Kavanaugh.

Kavanaugh was born in Washington, DC, and like many other Supreme Court justices, he grew up surrounded by the law. When he was 10, his mom Martha, who had until that point taught history in DC public schools, decided to go to law school and become a prosecutor. Martha would practice her closing arguments at the dinner table at their home in the DC suburb of Bethesda, MD, using her trademark line: “Use your common sense. What rings true? What rings false?”

After serving as a prosecutor, Martha Kavanaugh became a circuit court judge. From then on, even after he became a judge himself, Brett would think of his mother when he heard someone say “Judge Kavanaugh.”

Brett excelled academically from an early age at the private schools he attended. In seventh grade won the Headmaster’s Award recognizing academic excellence and personal integrity, and the school waived a year of tuition.

At Georgetown Prep (a private school also attended by Justice Neil Gorsuch, who was two years behind Kavanaugh), Brett was a standout student who consistently received top rankings in his class. Teachers and coaches describe him as respectful and reliable in class and as a teammate, serving as captain of the basketball team and defensive back for the football team.

Friends say Kavanaugh was a part of a tight-knit group that stayed close years after high school ended. Most of them played football, though they also played board games, had their own language, and built traditions amongst themselves.

The group was also known for partying, hard.

In 1983, Kavanaugh wrote a letter to his high school friends about renting a “beach week” house in Ocean City, MD, saying the first arrivals should “warn the neighbors that we’re loud, obnoxious drunks with prolific pukers among us.” Four Georgetown Prep classmates say they saw Kavanaugh binge-drink many weekends, and in his senior year yearbook, Kavanaugh listed himself as the treasurer of the “Keg City Club – 100 Kegs or Bust,” a reference, according to a later memoir, to the group’s goal of trying to drink 100 kegs in a year.

One of Kavanaugh’s closest friends, Mark Judge, wrote that memoir, and in it he said the school was “positively swimming in alcohol, and my class partied with gusto — often right under the noses of our teachers.” In a 2019 book, The Education of Brett Kavanaugh, journalists Robin Pogrebin and Kate Kelly write, “while not typically the instigator of bad behavior, [Kavanaugh] often readily participated in it.”

During a 2015 speech, Kavanaugh said, “We had a good saying that we’ve held firm to this day, which is ‘What happens at Georgetown Prep stays at Georgetown Prep.’ That’s been a good thing for all of us.”

Kavanaugh went on to Yale, the school his grandfather graduated from in 1928. He thought he’d become a history teacher and maybe a coach, and was “tireless about studying,” according to a classmate who had the room adjacent to Kavanaugh freshman year.

He decided instead to follow his mother’s footsteps and be a prosecutor, because he had always been deeply interested in the stories she’d tell of her work.

So he moved straight from undergrad to Yale Law School in 1987, where he didn’t make as big a name for himself amongst the student body as he did in high school. He was quiet, sticking to the back of classrooms and holding no leadership positions. But he made connections with professors by visiting office hours and playing basketball with them. These professors, like George Priest, were known for helping students get clerkships. He also joined the Yale chapter of the Federalist Society, a conservative legal organization.

Kavanaugh earned a summer associate position at law firms all three years, and two clerkships right out of Yale, the first in March 1989 with Judge Walter Stapleton of the US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. After his time with Stapleton, he got a call from Professor Priest, who asked if he wanted another clerkship with conservative Judge Alex Kozinski of the Ninth Circuit’s chamber. Friends say this was the job that solidified Kavanaugh’s own conservative views.

Another clerk, Lehman, said “You cannot understand Kavanaugh’s philosophy as a judge without understanding Kozinski’s judicial philosophy. Everything about Kavanaugh – how he interprets a statute, the role of regulatory agencies, the Second Amendment, the death penalty, abortion, even how many times he drafts an opinion – is influenced by that clerkship and the years he stayed in touch with him. You keep part of that voice with you throughout your career.”

Kozinski and Kavanaugh sat on panels together, coauthored a book, and both served on the Judicial Conference, which helps make policy for federal courts. Years later, Kavanaugh was dealt a blow when he found Kozinski was accused of sexual harassment by multiple women. Kavanaugh has denied knowing about the allegations or abuse.

After leaving Kozinski’s chambers, Kavanaugh’s trajectory skyrocketed, helped along by his next boss: Ken Starr. Kavanaugh received a fellowship with Starr from 1992-93 at the office of the United States Solicitor General.

After another clerkship with Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy the following year – Starr asked him to come back to work with him at the Office of the Independent Counsel.

It was here that Kavanaugh got deeply involved in some of the most dramatic cases in DC, including opening an investigation into Vincent Foster’s death, who served as deputy White House Counsel during the early months of Clinton’s presidency. His death was originally ruled a suicide, but conspiracy theories quickly circled. After three years, Kavanaugh also ruled the death was a suicide, and critics complained the investigation was a waste of resources and time.

The investigation of Foster’s death was the only time Kavanaugh argued in front of the Supreme Court. His position was that attorney-client privilege didn’t matter because Foster was deceased, and therefore any communication with his lawyers was no longer privileged. Kavanaugh lost the case.

After Foster’s case came the investigation into Bill Clinton. It is during this work that Kavanaugh began to believe in a broad view of executive power, writing that “the job of the President is far more difficult than any other civil position in government,” he wrote later in an article. He said, “I believe that it is vital that the President be able to focus on his never-ending tasks with as few distractions as possible.”

After Clinton left the White House, Kavanaugh went from investigating what happened in the Oval Office to working in it. First, Kavanaugh joined the legal battle in the recount for president between George W. Bush and Al Gore, a fight that ultimately helped win Bush the presidency, and then he was hired by Bush’s White House Counsel, Alberto Gonzales.

It was in part thanks to Gonzalez that Kavanaugh moved on to a federal judgeship. A colleague, D. Kyle Sampson, thought Kavanaugh would make a good judge, so asked him if he’d ever be interested. Kavanaugh said yes, and Sampson ran word up the grapevine. Gonzalez told Bush, who nominated him to the Court of Appeals for DC in 2003. His confirmation was blocked for years by Senate Democrats who believed Kavanaugh was too partisan, citing his work with Starr.

Democrats were blocking a lot of judicial confirmations at the time, and so a bipartisan group of Senators decided to end the turmoil. Because of the holdup, Republicans were threatening to get rid of the Senate’s ability to filibuster judicial nominees. So in order to save the filibuster, Democrats agreed to stop blocking some nominees.

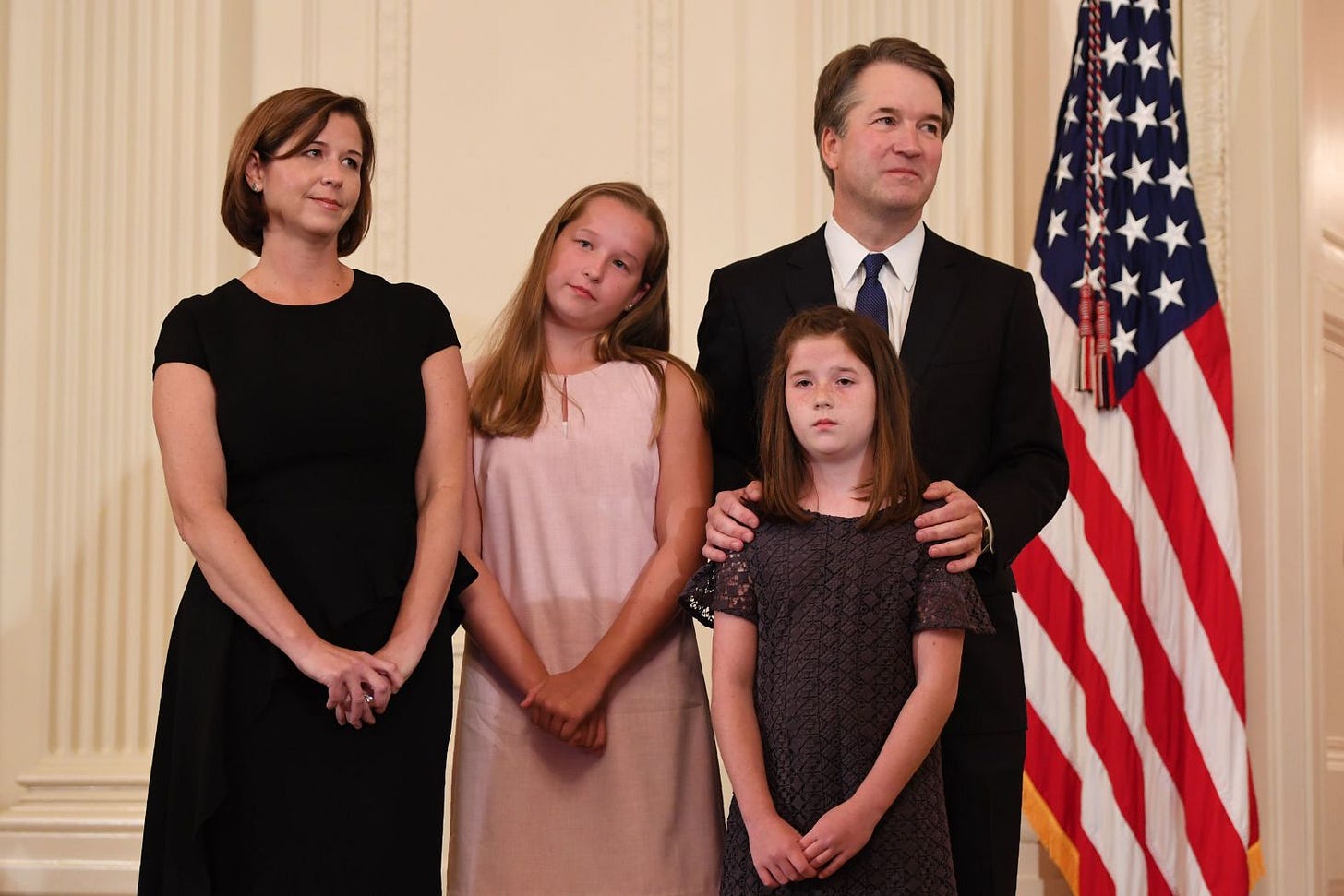

Kavanaugh was confirmed to the appeals court 57 to 36 in May 2006. He and his wife settled in Chevy Chase, MD with their two daughters. Off the bench, Kavanaugh became known for directing traffic at the annual Fourth of July parade, coaching his daughters’ basketball games, and grabbing a beer and a burger at a local restaurant. He was “no different than any dad in the neighborhood” and though his mostly Democratic neighbors knew they disagreed on a lot politically, they believed he was “eminently qualified” when he was nominated on July 9, 2018 by Donald Trump to join the Supreme Court.

The news came after Justice Anthony Kennedy announced he was retiring. Trump liked Kavanaugh’s rulings showing skepticism of regulatory agencies, the fact he was associated with the Federalist Society, and his ten years on the Court of Appeals.

But if he thought his confirmation to the appeals court was hard, it was nothing compared to what came next.

At first, it seemed he had the votes in the Senate. But then, a letter written by a woman alleging Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her while they were in high school was released. Christine Blasey Ford, who went to a high school near Georgetown Prep, wrote the letter to her California congresswoman, Democrat Anna Eshoo, when she heard Kavanaugh was on the short list of who might replace Kennedy. She then sent a letter to Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who at the time was the ranking Democrat on the Judiciary Committee. Ford asked her to keep the letter confidential.

The letter details a night sometime in 1982 when Ford was 15 and Kavanaugh was 17. About five of them were hanging out at a friend’s house, when Ford claims Kavanaugh and his friend, Mark Judge (who wrote the book about Georgetown Prep’s partying days) pushed her into a bedroom and locked the door. They turned on loud music and Kavanaugh, who Ford says was "stumbling drunk,” tried to pull off her clothes and groped her. When she tried to scream, she says he covered her mouth with his hand. Ford wrote that she “thought he might inadvertently kill me. He was trying to attack me and remove my clothing.” She claims the boys were laughing when it happened.

She was able to get away when Judge jumped on the bed and they all tumbled off. Ford says she fled to a bathroom and locked the door, quietly waiting until she heard Kavanaugh and Judges’ voices fade away before finally running out of the house.

Ford originally planned on staying anonymous, out of concerns of what this would mean for her family, but her story leaked. Reporters started coming to her house, and she saw that misinformation was being spread about her. Everything she had hoped to avoid was happening anyway, so she decided to come forward. In an interview with The Washington Post, Ford said the attack “derailed me substantially for four or five years,” including academically, socially, and in healthy romantic relationships with men.

She didn’t discuss the attack with anyone for years. Not until she and her husband were redoing their house and she found herself insisting that they needed a second front door and her husband didn’t understand why. It was then, during a couples therapy conversation about the door, that Ford shared details, including Kavanaugh’s name. She says she needed the second door so she could always escape, like she did that night. After her story was released, media reports confirmed various therapist notes that discuss Ford telling her story.

In light of Ford coming forward, Kavanaugh’s confirmation was postponed, and they were both asked to come testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee. Two other women then accused Kavanaugh of sexual misconduct. Deborah Ramirez said Kavanaugh exposed himself to her at a dorm party at Yale. Julie Swetnick said she grew up in the DC area and met Kavanaugh and Judge at a house party in 1980 or 1981. In a sworn declaration, Swetnick said she attended parties with them over the years and saw both “drink excessively and engage in highly inappropriate conduct, including being overly aggressive with girls and not taking ‘No’ for an answer. This conduct included the fondling and grabbing of girls without their consent.”

Kavanaugh denied all three women's accusations.

The Judiciary Committee asked for a supplemental background investigation to be conducted following the accusations (this is not the same thing as a criminal investigation). The Committee agreed to a one-week investigation. The FBI “upon direction from the White House,” according to a report, conducted ten interviews and opened a tip line for the public to call. The FBI then “concluded its investigation, and submitted all the information it gathered to the White House.” The White House passed along the information to the committee.

The FBI found “no additional corroborating information” that suggested Kavanaugh committed sexual assault.

The FBI did not speak to Ford (who requested to be interviewed but was denied) or Kavanaugh.

On Sept. 27, 2018, Ford testified in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee, who brought in an independent sex crimes investigator to question her. Ford said she would never forget the night of the assault and “the laughter, the uproarious laughter, and the multiple attempts to escape, and the final ability to do so.”

Ford said that since her story came out, her family had been subjected to constant threats. She said the hateful messages she’s received have “been terrifying and have rocked me to my core.” She and her family had to move locations multiple times to stay safe.

Kavanaugh’s testimony followed.

He came in angry, his face contorted. He appeared to alternate between nearly shouting and being on the verge of tears. “This whole two-week effort has been a calculated and orchestrated political hit, fueled with apparent pent-up anger about President Trump and the 2016 election, fear that has been unfairly stoked about my judicial record. Revenge on behalf of the Clintons and millions of dollars in money from outside left-wing opposition groups. This is a circus.” He said talking to his daughters about Ford’s allegations was the worst experience of his life.

His wife sat behind him, chin quivering as she was trying to hold back tears.

Democratic Senators asked about things written in Kavanaugh’s high school yearbook and his drinking habits like if he’d ever passed out from drinking or drank so much he couldn’t remember — he said no to both. They questioned his temperament.

Republican Senators apologized to Kavanaugh, with Sen. John Cornyn saying, “Judge, I can’t think of a more embarrassing scandal for the United States Senate since the McCarthy hearings.”

But the most noteworthy exchange came when Senator John Kennedy asked Kavanaugh if he believed in God. Kavanaugh, a Catholic, said he did.

Kennedy said, “I’m going to give you a last opportunity right here, right in front of God and country. I want you to look me in the eye. Are Dr. Ford’s allegations true?”

Kavanaugh looked at him and said, “They’re not accurate as to me. I have not questioned that she might have been sexually assaulted at some point in her life by someone someplace. But as to me, I’ve never done this.”

Kennedy reiterated: “None of these allegations are true?” Kavanaugh told him he was correct.

“No doubt in your mind?”

“Zero. 100 percent certain.”

“Not even a scintilla?”

“Not a scintilla. 100 percent certain, Senator.”

“Do you swear to God?”

“I swear to God.”

The hearing ended there.

Days later, on Oct. 6, 2018, protestors shouted “shame on you” and “I do not consent” from the Senate gallery as the confirmation vote began. Outside, more protestors pushed past the police and banged on the doors of the Supreme Court doors. That day, the Senate confirmed Kavanaugh in a 50-48 vote. It was the closest confirmation vote in more than 150 years.

At least 164 protestors were arrested the day of his swearing in. They shouted, “Hey hey, ho ho, Kavanaugh has got to go,” and “shut it down,” and “we believe survivors.”

Since joining the Court, Kavanaugh has stayed true to the conservative views he solidified as a young lawyer. He has voted most frequently with the conservative majority, including on overturning the federal right to abortion and voting against affirmative action. And in July 2024, Kavanaugh voted in the majority to give the president broad immunity for any official acts taken while in office.

The man who cut his teeth early in his career investigating a president was now ruling that a president has “absolute immunity from criminal prosecution” for his official acts.

In October 2024, Rhode Island Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, Chair of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Federal Courts, released a report from a years-long investigation about the FBI’s supplemental background research into Brett Kavanaugh. The report claims Trump’s administration limited the FBI’s investigation into Kavanaugh, and that the FBI did not have the freedom to conduct a “thorough, complete investigation.” The report also claims the tip line the FBI set up was fake, and though it received 4,500 calls, no tips were investigated.

At the time of the background investigation, Trump said the FBI could "interview whoever they deem appropriate, at their discretion.” The Senator Whitehouse report says these claims were blatantly not true, and that instead, nearly 600 pages of communications between the White House and the FBI showed “the Trump White House maintained strict control over the FBI’s supplemental background investigation, confining it to ‘limited inquiry’ interviews of specific individuals on specific topics and denying authorization to interview others. The FBI did not interview Ford or Kavanaugh, for example, because the Trump White House refused to allow it.”

The FBI also interviewed only people with “firsthand knowledge” of the allegations, ignoring anyone who had details that could corroborate the accuser’s accounts but who weren’t at the event. Ford and Ramirez had both given the FBI a list of suggested witnesses who could corroborate their stories, and members of the Judiciary Committee who heard from people hoping to get in touch with the FBI reached out on those people’s behalf. But, the report claims, “the shutters were closed, the drawbridge drawn up, and there was no point of entry by which members of the public or Congress could provide information to the FBI.”

Kavanaugh likely has decades left on the court. He has now been a part of some of the biggest stories in DC. What role will he have in stories of the future?

Time will tell.

Correction: A former version of this article said Brett Kavanaugh sent a memo on August 15, 1990. The article has been corrected to show the date was August 15, 1998.

Why are men still being allowed to sexually assault women and get away with it? It's extremely hard to have faith in the judicial system when this continues to happen over and over. My hope is that powerful men who are sexual predators have a special place reserved for them in hell. Not interviewing Ford or Kavanaugh during the FBI investigation? Disgraceful. Not surprising given Trump was involved.

4500 tips and not one was investigated. And now they are set to confirm an entire cabinet full of sexual predators. For all of the awareness that the Me Too movement created, little has changed. Powerful men are never held accountable. Women are dismissed as liars.