What’s Hidden in the Budget Bill?

Don’t be fooled by what you see on social media

President Trump’s signature package to cut taxes, increase defense and border security spending, and reduce the social safety net is officially titled the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

Whether or not you think it’s beautiful, it certainly is big. The full package is 1,082 pages long, roughly the size of Don Quixote. That means there’s plenty of room for lawmakers to sneak in all sorts of pet priorities and under-the-radar provisions.

Sharon already covered the big-ticket parts of the bill last week: the cuts to Medicaid and food stamps, the elimination of numerous clean energy tax credits, the changes to student loan programs. Today, we’re diving deep into the package to fill you in on the less attention-grabbing — but still crucially important — parts of the bill you haven’t heard about:

Contempt of court

Some of the biggest clashes of Trump’s presidency so far haven’t taken place between Democrats and Republicans: they’ve been between the executive and the judiciary. Trump has repeatedly lashed out at judges as they’ve struck down a slew of his executive actions, sparking fears that he might choose not to follow their decisions.

If the executive branch doesn’t comply with judicial orders, the biggest weapon judges have is the ability to hold officials in contempt, which can come with monetary fines or even jail time. That possibility isn’t as hypothetical as you might think: three separate judges have suggested they might hold the Trump administration in contempt for allegedly flouting court orders.

But the One Big Beautiful Bill would make this harder. It does so by invoking Rule 65(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the guidebook that governs the federal courts. That rule covers the tools courts use to temporarily block defendants from taking certain actions while litigation plays out, which judges have done more than 100 times to pause Trump policies so far this term.

Under Rule 65(c), courts can issue those temporary blocks only if the people challenging an action first post bond, putting up enough money to pay for the costs of the temporary pause if it turns out that the underlying action was legal all along. The idea here is to avoid frivolous lawsuits: you can still ask a court to temporarily stop something from happening if you think it’s illegal, but to do so, you have to show you can pay for the damages if you end up being wrong.

For example, let’s say the government tries to fire a bunch of employees, and the employees ask to be temporarily reinstated while the courts are deciding whether their firings were illegal. If the government is going to pay their salaries during this temporary period, the employees need to be able to show they could pay that amount back if it turns out their firings were legal after all. Otherwise, the government will be in the hole, having paid several weeks or months of salaries that there was no legal need for them to have paid.

The reality, though, is that Rule 65(c) is basically never followed, at least not when the government is the defendant. Most judges in those cases waive the rule, reasoning that someone shouldn’t have to put up money when they’re challenging potential threats to constitutional rights, even if that means the government sometimes has to bear the costs of holding off on an action that ends up being ruled legal.

A provision tucked into the Republican megabill would put an end to that, emphasizing the existing rule that courts collect these bond payments from plaintiffs before temporarily blocking government actions — and adding a consequence if they don’t. Under the bill, if no bond money was posted before a pause was put in place, the court won’t be able hold the government in contempt for flouting the court’s temporary order.

As it’s currently written, the provision would even appear to take effect retroactively, blocking judges from holding officials in contempt if no bond was collected at the time a temporary block was issued. That means, depending on how judges with active temporary orders respond, that the Trump administration could try to evade contempt proceedings over temporary blocks they’ve allegedly ignored in the past few months, since no bond was collected in those cases.

The rule has a pretty big question mark: the amount of the bond is entirely determined by a judge. A plaintiff could be asked to post a bond worth millions, they could be asked to pay $1, or any number in between. But the budget legislation could add pressure to some judges to take Rule 65(c) more seriously, forcing challengers to future Trump policies to think about whether they’re prepared to pony up if they want to temporarily restrain the government.

And if they still decide to request a pause, plaintiffs would be incentivized to make smaller asks. At the same time as the Trump administration is pushing the Supreme Court to do away with nationwide injunctions — the ability of district court judges to pause executive branch policies across the country — this change would seek to dissuade plaintiffs from even requesting them.

After all, to return to our hypothetical, asking to get thousands of employees across the country their jobs back might come with a hefty price tag. Now, if plaintiffs seek a temporary pause on that sort of firing, they might ask only for a reprieve they can afford, for a smaller, more targeted group.

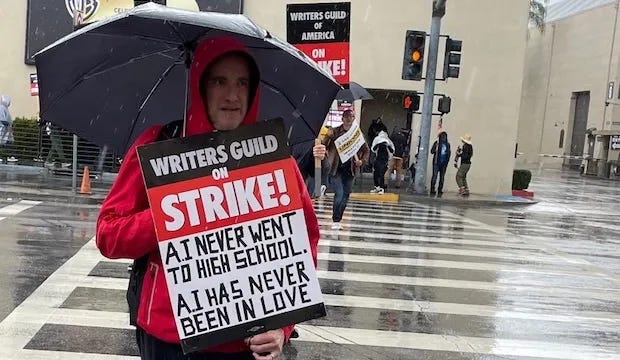

AI regulations

If there’s one thing I’ve learned covering politics, it’s that the government can reliably be counted on to tackle everything on a two- or three-year (or more) time lag.

ChatGPT launched towards the end of 2022, so of course governments are just now catching up to the need to make policies surrounding artificial intelligence. Without many tech laws being passed in Washington, AI has become fertile ground for legislating (including on a bipartisan basis) on the state level. According to the National Council of State Legislatures, AI-related bills have been introduced in 48 states so far this year; more than 75 of those bills, in 26 different states, have already become law.

But potentially not for long. Under the Big Beautiful Bill, all states would be prohibited from enforcing any laws “limiting, restricting, or otherwise regulating artificial intelligence models” for the next 10 years.

The bill makes clear that state laws intended to “remove legal impediments” to the development of AI systems will still be allowed, but any regulations hampering AI systems would have to come from the federal level. “We believe that excessive regulation of the AI sector could kill a transformative industry just as it’s taking off,” Vice President JD Vance said in February; if certain regulations are necessary, Republican lawmakers believe they should come in a coordinated fashion from Washington, rather than requiring companies to wade through up to 50 conflicting regulations coming from the states.

“Trump accounts”

The idea of the government giving money directly to parents after they welcome a newborn — sometimes known as “baby bonuses” — isn’t new. In fact, it’s been proposed by members of both parties for years.

Republicans are moving forward with a version of this idea in their megabill, even if you wouldn’t be able to deduce its bipartisan origins from the name given to the policy.

The package would create a new type of tax-deferred investment account that would open when a child is born and be accessible by them only once they turn 18 years old. Parents will be able to put up to $5,000 a year into the accounts; for any children born from the beginning of 2025 to the end of 2028, the US government will contribute $1,000, a sort of pilot program for the “baby bonus” idea.

In the original version of the package, these accounts were called “Money Accounts for Growth and Advancement,” or “MAGA Accounts.” In the latest draft, Republicans removed any subtlety: these “baby bonuses” have now been renamed “Trump Accounts.”

The Kennedy Center

The spending increases in the Republican megabill are mostly for the areas you would expect: securing the southern border, beefing up the nation’s military, etc.

You wouldn’t think there would be much new money in there for the arts, considering the Trump administration has been canceling grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and has proposed eliminating the agency entirely.

And there isn’t: except, that is, for the arts center that Trump has taken a personal interest in.

The GOP package includes almost $260 million in new funding to renovate the Kennedy Center over the next four years. Trump appointed himself chairman of the center after taking office, and has discussed his desire to touch up the facility.

Hobbling fired federal workers

When the government fires federal workers — which it has been doing a lot lately — the spurned employees can turn to the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), a low-profile but powerful agency which hears appeals from fired workers and can reinstate them if it finds they were dismissed wrongly.

The MSPB has been clogged with thousands of appeals since Trump took office; in one high-profile move, they ordered the temporary reinstatement back in March of almost 6,000 Agriculture Department workers who were DOGE’d out of their jobs.

The One Big Beautiful Bill doesn’t stop fired workers from bringing MSPB complaints — but it will put a new hurdle in their way. Going forward, fired employees would have to pay a filing fee before bringing claims to the MSPB. The fees would be refunded if the employees won their appeals.

Gun silencers

The National Firearm Act of 1934 is a cornerstone of US gun law, dictating the regulation and taxation of firearms in the country. The law uses a somewhat expansive definition of “firearm,” which includes silencers (also known as suppressors), devices that attach to the barrel of a firearm and muffle the sound of a gunshot.

The GOP megabill would strike silencers from that definition, removing registration requirements for the devices and getting rid of the $200 tax for buying a silencer and the $200 tax for manufacturing one.

Will all of this become law? Maybe!

The One Big Beautiful Bill is advancing through “reconciliation,” a very specific legislative process that I’ve written about before. It allows major packages to be pushed through along party lines, but only if they comply with a certain set of rules.

Now that the House has passed the package, the Senate parliamentarian (the keeper of the chamber’s rules) will examine the bill to make sure it complies. The key test is the Byrd Rule, which requires that everything in a reconciliation bill be fiscal in nature: any provisions that don’t touch taxes or spending — or for which changes to taxes or spending are “merely incidental” to the provision — can be struck.

This is known as going through the “Byrd bath”; anything that gets struck from the package is called a “Byrd dropping.” (Who said Congress doesn’t have a sense of humor?)

Democrats are sure to argue that several of the provisions we’ve covered today — like the one on contempt or the one on state AI regulations — have only an “incidental” impact on the federal budget. If the parliamentarian agrees, they might get struck from the bill, although ultimately, members of Congress have the final say – the parliamentarian’s opinions are advisory and not binding..

Senators have never exercised their prerogative to overrule the parliamentarian during the reconciliation process, although the GOP chose to overrule the rulekeeper in a separate vote last week and could do so again with the reconciliation bill.

Ultimately, if 51 members of the Senate want to keep a provision in the package, it can stay in, Byrd Rule or not.

This was a really helpful breakdown - thank you. I’m still trying to wrap my head around the bigger picture here. Aside from the $5,000 “Trump Account” for newborns, which feels more like a flashy headline than a broad policy solution, I’m struggling to see how this budget bill meaningfully serves the average U.S. citizen.

So much of it seems geared toward consolidating power or shielding the administration from accountability—like making it harder to file injunctions against the government or limiting states’ ability to regulate AI. Am I missing something? Are there tangible benefits for working families, healthcare access, education, or affordability tucked away in here? Because from where I sit, it feels more like a self-protection bill than a people-first budget.

So we get rid of the tax revenue on gun silencer purchases and manufacturing and reduce SNAP benefits for poor people. This will never be okay with me.