Trump v. the Supreme Court

Why he’s raging against his own appointees

Donald Trump has been on a tear lately, raging against all manner of rivals on Truth Social. Bob Iger. Jay Powell. Bruce Springsteen. The Supreme Court.

Wait, the Supreme Court?

Wasn’t this supposed to be the Court that would rubber-stamp everything Trump did, after its decision to largely grant him immunity from prosecution last year?

Not so fast. The relationship between Trump and the nine justices, even the ones he appointed, is much more complicated than that — as I was able to see firsthand last week.

But to fully unpack their tangled ties, we have to start at the beginning. The saga of Donald Trump and the Supreme Court is a love/hate story in four parts.

In Part I, the Court — not the justices themselves, but the idea of the Court — helps him get elected.

It’s hard to remember now, but as recently as 2016, many Republicans viewed Trump with suspicion. He was an untrustworthy interloper, a literal party-crasher. Many top conservatives who are now known for their unwavering devotion to him — from Vice President JD Vance to Secretary of State Marco Rubio to House Speaker Mike Johnson — were highly skeptical of his campaign.

But these politicians (and legions of Republican voters) were united by their opposition to abortion and their desire to see Roe v. Wade overturned. When Justice Antonin Scalia, the godfather of the Supreme Court’s conservative wing, died in February 2016 and Senate Republicans held the seat open for the next president, the stakes in that year’s election got higher. If Republicans wanted a conservative to keep Scalia’s seat (and they did), they had to rally behind Donald Trump. The risk of seeing their hero’s seat (and the Court’s majority) fall into liberal hands was simply too much to bear.

So Trump was elected, partially fueled by conservative hopes and fears surrounding the Supreme Court.

In Part II, Trump transformed the Court, nominating not just Neil Gorsuch to succeed Scalia, but two more justices (Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett) as well. By the time he left office, fully one-third of the justices were his appointees. No president since Ronald Reagan had left such a mark on the high court.

In the traditional parlance, which names eras of the Court after the chief justice, this was still the John Roberts Court. But now it was the Trump Court, too.

In Part III: Trump and the Court he built begin to navigate each other. It would be a rewriting of this phase to say that everything was hunky-dory during this time.

In fact, according to research by Professors Lee Epstein and Rebecca Brown, Trump’s first-term success rate in front of the justices (37 wins, 48 losses) was worse than any president’s going back to FDR. The Court declined to take his side on important matters ranging from the US census to his 2020 election defeat.

But he scored wins on other key issues — and then, after he left office, on two of the biggest cases in decades: the 2022 ruling striking down Roe v. Wade, and Trump v. United States, the 2024 ruling on presidential immunity from prosecution. Both decisions were issued during Trump’s four years out of power.

On the 2024 campaign trail, Trump cheered both decisions — and boasted of his role in bringing them about. He happily took credit for the abortion decision, presenting it as proof that conservatives had made the right gamble in supporting him. “I was able to kill Roe v. Wade,” Trump bragged, as if he and the Court were interchangeable, on account of his having installed the deciding justices.

After the immunity ruling, a popular view began to take hold that Trump would be able to do no wrong in the Court’s eyes.

This would be the peak of their relationship.

Part IV has been all about the downfall.

Trump reentered office this January determined to expand the powers of the presidency and test its legal limits. But he quickly ran up against the courts.

Trump’s first second-term clash with the Supreme Court involved his expressions of frustration towards the lower-court judges who were ruling against his policies. In March, Chief Justice Roberts issued an incredibly rare statement. Without naming the president, he rebuked Trump’s call for judges who ruled against the administration to be impeached.

Since then, the Court has begun considering some of those policies that lower-court judges have blocked — and the results haven’t always been positive for Trump. Particularly on two key immigration matters, the justices have ruled overwhelmingly against him. They directed his administration to provide immigrants advance notice before deporting them under the Alien Enemies Act, and they told it to “facilitate” the return of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, the alleged gang member who was mistakenly deported to El Salvador.

Many, many presidents have squabbled with the Supreme Court before, Trump included. Roberts also pushed back against Trump’s rhetoric towards the judiciary in 2018. In 2020, according to one book, Trump was infuriated that the justices he appointed didn’t take his side in election-related lawsuits.

But Trump’s second term has ratcheted tensions between the executive and judicial branches higher than at any point in recent memory. Some of Trump’s allies have urged him to flout the Supreme Court’s orders. Two lower-court judges are probing whether he is ignoring theirs. And he has taken to rage-posting about judges on social media, urging Republicans to remove them and even seeming to suggest that he should be above their orders. “He who saves his Country does not violate any Law,” he wrote in February.

This complicated history — and contentious recent stretch — served as the backdrop for a hearing I attended last Thursday, which marked the first Supreme Court arguments for a case involving Trump since the start of his second term.

The case concerned Trump’s executive order attempting to bar children of illegal immigrants or temporary visitors from receiving birthright citizenship. But really the justices were focused on a separate issue: whether lower-court judges are allowed to issue nationwide injunctions, which can temporarily block the president from carrying out orders across the country.

It was the first opportunity to see in person how the justices would handle the new administration and whether they were prepared to remove a key tool that judges have used to rein Trump in.

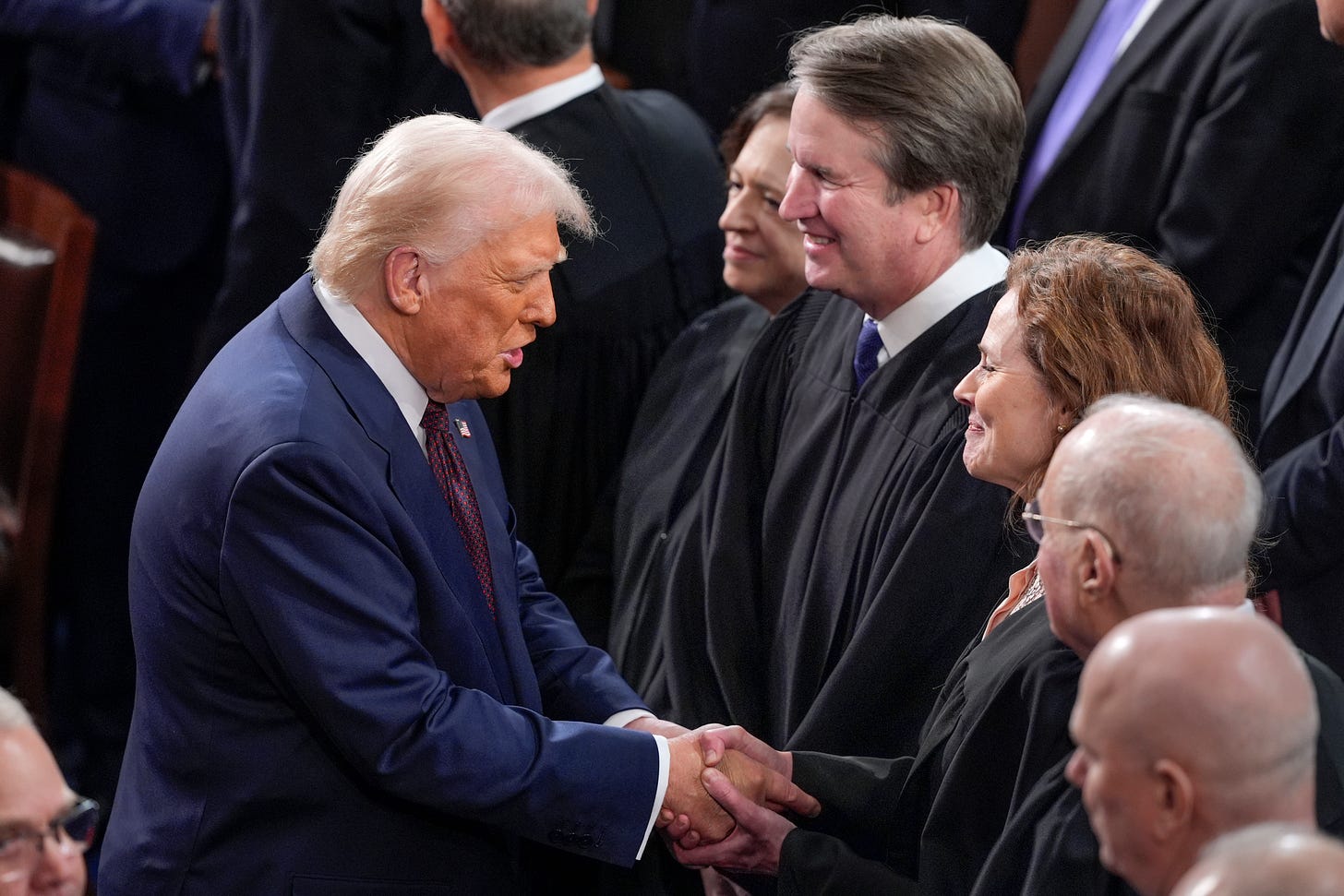

My biggest takeaway from the session was that whatever goodwill once existed between the Trump administration and the justices seems to have evaporated. Especially among his own appointees.

Justice Barrett grilled John Sauer, the Trump administration’s lawyer, on whether the administration would commit to following a circuit court ruling blocking a presidential order in the entire area that the court had jurisdiction in, or only stop enforcing it against the specific individuals who sued.

Sauer told her it was their “general,” but not “categorical,” practice to follow the precedent circuit wide. “Really?” Barrett responded in disbelief. (Typically, circuit court orders are seen as applying to their entire area of jurisdiction.)

Later, when Justice Elena Kagan pointed out that if nationwide injunctions were struck down, the Trump administration could simply accept its losses at the lower-court level and decline to take a case to the Supreme Court to avoid setting a nationwide precedent, another Trump appointee seemed to share her concerns. “Justice Kagan asked my questions better than I could have,” Justice Gorsuch said.

Justice Kavanaugh added his own skepticism about the logistics of implementing the birthright citizenship order, repeatedly prodding Sauer to explain how hospitals would handle birth certificates if not everyone born in the US is automatically assumed to be a citizen. In total, he pressed Sauer on this point five times; he seemed frustrated that he never got a clear answer.

Historically, the government benefits from what’s known as the “presumption of regularity,” the assumption on the part of courts that the government is acting in good faith.

Four months into Trump’s second term, that presumption appears to have collapsed. At the Supreme Court last week, even Trump’s own appointees seemed to treat his administration with more skepticism than they would others. At one point, when Sauer told Barrett that the administration wouldn’t necessarily obey circuit court orders across a court’s whole jurisdiction, Barrett drew a pointed distinction between Trump and his predecessors.

Was Sauer referring to “this administration’s practice or the longstanding practice of the federal government?” she asked.

Later, Kavanaugh felt a need to ask Sauer whether the administration would commit to stopping enforcement of a policy nationwide if the Supreme Court struck it down. Sauer answered “Yes,” but the fact that the question even had to be asked seemed to represent a gaping trust deficit between Trump and the Supreme Court.

I exited the oral arguments with the sense that the justices — Trump’s appointees very much included — were losing trust in the administration.

It took less than 24 hours for my sense to be confirmed. Last Friday, the justices issued their latest ruling on the Alien Enemies Act; for the fourth time, they ruled that migrants being deported under the 1798 law must be accorded due process.

One of their reasons? “The Government has represented elsewhere that it is unable to provide for the return of an individual deported in error to a prison in El Salvador,” the justices said, referring to Kilmar Abrego Garcia, whom the administration has said they are powerless to bring back despite court orders mandating it. The Trump administration’s record of making mistakes in deportations — and refusing to correct them, even when ordered by the Court — was already being used against them.

Trump didn’t take that well. “THE SUPREME COURT WON’T ALLOW US TO GET CRIMINALS OUT OF OUR COUNTRY!” he raged on social media.

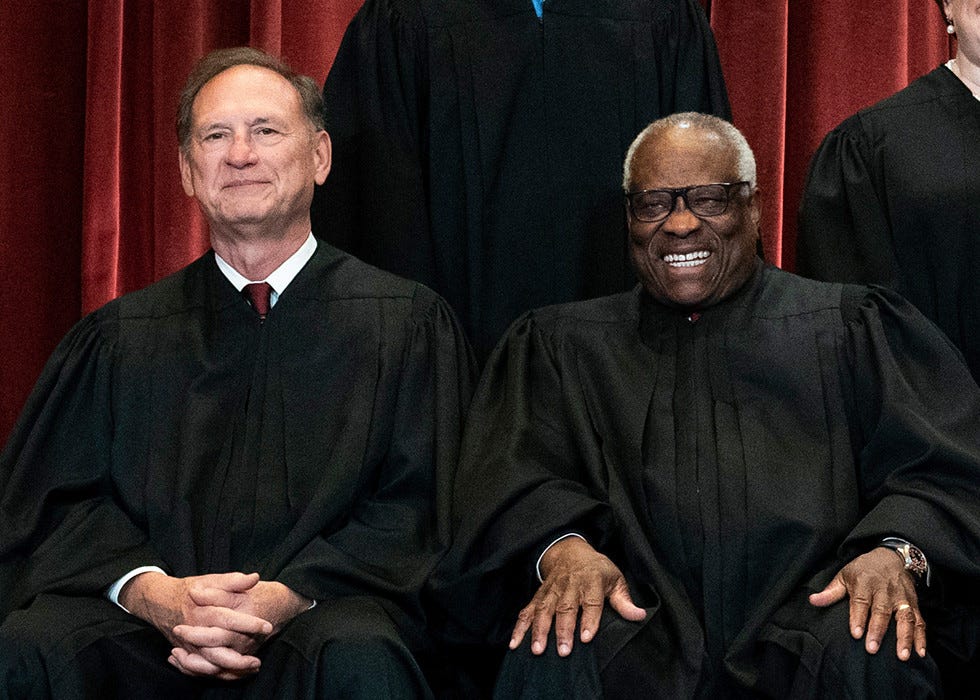

Notably, Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, conservatives whose service on the Court predates the Trump era, dissented. (“In any event, thank you to Justice Alito and Justice Thomas for attempting to protect our Country,” Trump wrote.) But Thomas and Alito weren't joined by any of the Trump appointees.

Mostly by accident, Trump nominated justices who are now less friendly to his agenda than justices appointed by the Presidents Bush. None of this means that Trump is going to lose every Supreme Court case, just as the immunity case didn’t mean every subsequent ruling would yield him a victory. In fact, the Court just ruled in his favor on Monday, in a case involving Venezuelan migrants.

But in his farthest-reaching attempts to skirt up against the law, such as his move on birthright citizenship, Trump appears able to count on the votes of only Thomas and Alito. Clearly, Trump’s appointees aren’t really his.

There are still many Trump cases to come before the Court. Some the president will win, others he will lose. But you don’t have to be a legal expert to understand this simple, human truth: any relationship that lacks trust isn’t likely to end happily.

Thanks again for this reporting, Gabe. It was written between the lines, but the change in tone of the justices' words doesn't necessarily mean they have a change of heart on Trump. I would say it much more has to do with the exponentially increased absurdity of what they are being given to consider this term. Had they accepted the arguments they were given, it would turn the court into even more of a farce than it already is.

But if that was the only explanation, how do we interpret the decision to grant a president much more immunity only a short while ago? Where were his appointees' pointed questions when Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson were asking all of the obvious horrifying questions, like what if a president orders an assassination? Did Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett have as much imagination then as they do now about how presidential power could be abused? In the immunity case, these same justices who are now grilling Trump's lawyers were remarkably deferential to expansive claims of executive power. Gorsuch focused on protecting "official acts" from prosecution, Kavanaugh worried about chilling future presidents, and Barrett seemed more concerned with procedural questions than the substantive dangers Sotomayor was highlighting. Their skepticism appears highly selective, but this does indicate a major shift that can't be fully explained by the quality of arguments being presented to them.

I also just want to put into context how crazy it is that THIS court isn't Trumpy enough for Trump. We're talking about a Supreme Court that should already be considered illegitimate because it has no relationship to voters' opinions on who placed the justices there. Remember that Republicans told us to "let the American people decide" when they blocked Obama from filling Scalia's seat for nearly a year, claiming it was too close to an election. Then they rammed through Barrett's confirmation just weeks before the 2020 election, abandoning their own stated principle the moment it became inconvenient. This was orchestrated by Mitch McConnell, who was ironically the least popular senator with his own constituents among all 100 senators while making these pleas about listening to the American people. Republicans argued it would be unfair for Obama to get a third Supreme Court pick in eight years, then turned around and crammed three appointments into Trump's four-year term. The result is a court where a president who lost the popular vote twice was able to appoint one-third of the justices, backed by a Senate majority representing far fewer Americans than the minority party, and confirmed by senators whose states collectively cast millions fewer votes than the states represented by the opposing senators. This entire saga has done more to harm the institution of the court than any sitting justices could. This is the illegitimate Supreme Court that Trump himself created, and somehow even this rigged institution isn't subservient enough for his tastes.

We need to reform the process by which justices are selected and how long they serve. Term limits of 18 years would ensure each president gets to appoint two justices per term, creating more regular turnover and reducing the incentive to nominate younger ideologues who will serve for decades. We should expand the court to 13 justices to match the number of circuit courts and dilute the outsized impact of Trump's appointments. The confirmation process should require a supermajority in the Senate, forcing presidents to nominate more moderate candidates who can actually build consensus. We could implement a lottery system where lower court judges are randomly selected from a pool of highly qualified candidates, removing political calculation from the selection entirely. Mandatory retirement ages would prevent justices from timing their departures for maximum political impact. These reforms would restore the court's legitimacy by ensuring it actually reflects the democratic will, rather than the accidents of political timing and Senate math.

I respect what this article is trying to say. But I hate that we’ve reached a point where the court occasionally saying no to Trump’s most damaging instincts is seen as some kind of signal that everything is okay. Meanwhile, SCOTUS is slow-walking a bunch of cases, handed Trump immunity, and seems to have no concern or urgency for Trump’s lack of due process for hundreds of immigrants. SCOTUS is doing the bare minimum, and this is our great hope? Ugghhhh.