The Supreme Court's Double Standard on Race

It ended affirmative action but allowed racial profiling for immigration enforcement

In June, President Donald Trump announced that US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) would be carrying out what he called “the single largest mass deportation program in history.” A senior White House adviser previously said that they even set a quota: “minimum 3,000 arrests for ICE every day.”

In pursuit of that goal, ICE employed a controversial tactic called “roving patrols,” operations where agents patrol areas without fixed checkpoints, stopping people based on observation alone. Across the Los Angeles area, masked ICE agents were bursting out of undercover vehicles at sites with Hispanic day laborers, demanding papers and detaining people who were in the country illegally — as well as US citizens and people legally residing in the US. A group of five people who were stopped or arrested during these raids joined with local and state organizations to file the class action lawsuit Noem v. Vasquez-Perdomo, leading to a temporary halt to the practice.

The Supreme Court’s response to that suit could signal a shift in the way the Constitution is interpreted, a change that may affect US citizens as much as it does undocumented immigrants. The Court’s unsigned September 8 order seemingly upends the precedent of not relying on racial profiling and places race squarely in the realm of what agents may consider, based on the “totality of the particular circumstances.” In the city of Los Angeles, where almost half the population identifies as Hispanic, the effects will be considerable, and as ICE operations move to other major US cities, the impact will spread across the country.

Noem v. Vasquez-Perdomo hinges on whether ICE’s tactics violate the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures and protects citizens and noncitizens alike. In order to stop and question someone, officers must at least have a reasonable suspicion that the person is involved in criminal activity. Reasonable suspicion is based on a set of facts, not a hunch or some other set of factors. The standard for arrest is even higher — probable cause that a crime has been or is being committed. ICE faced a clear challenge in Noem v. Vasquez-Perdomo: courts have held that, under the Fourth Amendment, race alone does not establish reasonable suspicion.

This was clearly established in a 1975 Supreme Court ruling that dealt with a roving patrol near the Mexican border. In United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, the Court ruled that because of the Fourth Amendment, immigration officers could not stop and question people about immigration status “when the only ground for suspicion is that the occupants appear to be of Mexican ancestry.” Rather, officers must be “aware of specific articulable facts” that are cause for suspicion. Even now, ICE must meet this standard — and be able to justify searches with specific and observable facts — or else its tactics are illegal.

That’s why the plaintiffs in Noem v. Vasquez-Perdomo set out to prove that ICE was relying on race, targeting people of Hispanic descent. For its defense, the government needed to show that ICE was not relying on race but on some other factor or factors.

To do this, the government named four factors ICE agents consider when making these stops: (1) apparent race or ethnicity, (2) limited English proficiency or Spanish-speaking, (3) place, and (4) kind of work. The government argued that it was not relying solely on race and that these four factors together amount to reasonable suspicion.

The plaintiffs argued that the four factors are just proxies for race. The district court sided with the plaintiffs, ordering a freeze on ICE’s roving patrols. The government appealed, and the Ninth Circuit Court also sided with the plaintiffs. The government appealed again, and the case went up to the Supreme Court’s emergency docket — a process that allows the Court to issue quick rulings on urgent matters without full briefing and argument.

The Supreme Court’s decision and the dissent

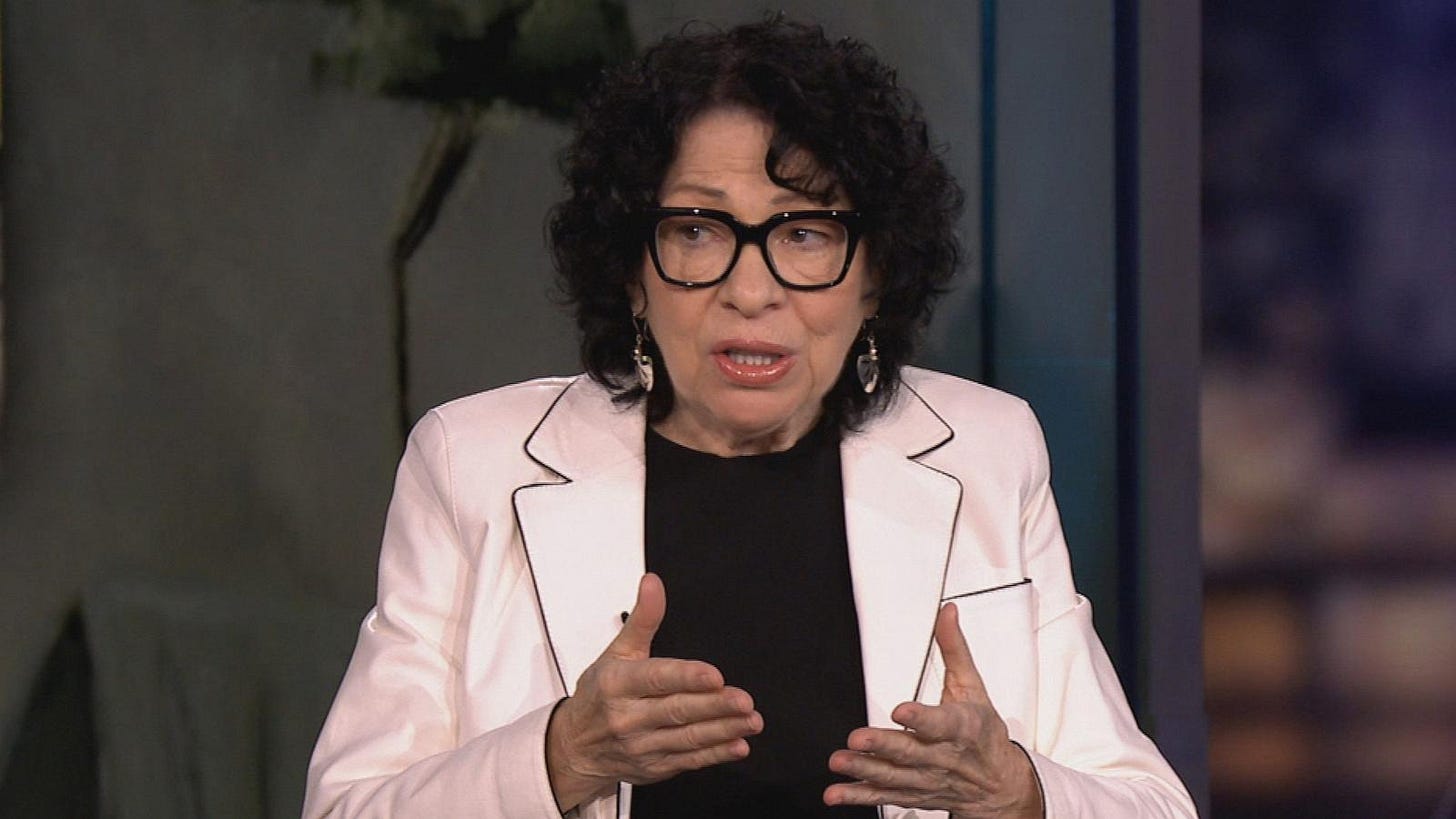

The Supreme Court issued a 6–3 decision in favor of the government. This decision, which was unsigned and without explanation, overturned the limitations the lower courts had set on ICE. Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote a concurring opinion in support of the decision, and Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote a dissent that was joined by the other two liberal justices.

Kavanaugh said that the Court was merely allowing “common sense” and lawful tactics. He stressed that the Court was not permitting racial profiling. “To be clear, apparent ethnicity alone cannot furnish reasonable suspicion.” However, this came with a caveat: apparent ethnicity “can be a ‘relevant factor’ when considered along with other salient factors.”

In her dissent, Sotomayor wrote, “We should not have to live in a country where the Government can seize anyone who looks Latino, speaks Spanish, and appears to work a low wage job.” Rebutting Kavanaugh’s claim that ethnicity alone is still not cause for ICE to target someone, she wrote, “Ethnicity and language are often intertwined, so relying on only those two factors is no different than relying on ethnicity alone.”

The Court sided with Solicitor General D. John Sauer — the government’s top Supreme Court lawyer — who said that the lower courts’ decisions put “a straitjacket on law-enforcement efforts.” The plaintiffs’ lawyers responded in a brief to the Court that the government’s argument came “very close to justifying a seizure of any Latino person in the Central District,” which they said “is anathema to the Constitution.”

Conflicting rulings

The Noem v. Vasquez-Perdomo supporting opinion and the dissent make no mention of the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause — the constitutional provision that guarantees all people “equal protection of the laws” and broadly prohibits government discrimination based on race. But Noem v. Vasquez-Perdomo has clear ties to other cases that DO consider the clause. When ending affirmative action in college admissions in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, the Supreme Court said that race could not be considered in admission decisions at schools that receive federal funding because the 14th Amendment does not permit any distinctions of law based on race, color, or nationality. That was in 2023. Now, just two years later, the same Supreme Court has ruled that immigration officials can detain an individual primarily for being brown-skinned and Spanish-speaking. What changed?

The apparent double standard by which race can be used in law enforcement but not in admission decisions came as a shock to California Attorney General Rob Bonta. He told Politico, “How they prevent the use of race to tackle discrimination, but allow the use of race to potentially discriminate is troubling and it is disturbing.”

Stanford law professor Jennifer M. Chacón also pointed out the inconsistency, writing, “The Court’s endorsement of racially discriminatory policing is very difficult to reconcile with its hard line against any reliance on race in other contexts.”

The future of immigration enforcement

Following the decision, ICE resumed its patrols. In Los Angeles, ICE has been given license to keep “detaining people without evidence or due process simply because of the color of their skin, the language they speak, or the work they do,” according to Mark Rosenbaum, an attorney at the nonprofit law firm Public Council.

The American Immigration Council says, “Crucially, this order is not a final ruling, but it strongly signals the Supreme Court will not uphold strict constitutional limits on the authority of immigration agents.” We don’t yet know if or when the case will make its way back to the Supreme Court.

In the meantime, the American Immigration Council predicts, “we can expect federal agents to be emboldened by this decision” as it “ramps up immigration raids in other cities like Chicago.”

Chacón laments that “at a time when federal immigration enforcement agencies are receiving a massive expansion to their budgets,” they are being empowered to employ “the most chaotic and discriminatory enforcement strategy they possess.” Because there are a number of ways to enforce immigration law through just means, such as immigration status inquiries, Chacón says, “the choice that has to be made is not between racial profiling or no immigration enforcement at all. The choice is between discriminatory forms of immigration enforcement” and “nondiscriminatory immigration enforcement.”

Any one else have their “go bag” packed and ready? All three branches of government are filled with this twisted thinking. If the Court wasn’t so messed up with these screwy life time appointees I’d think that mayyybe we have a fighting chance. We do not. Add on top of this that Trump doesn’t govern. He’s campaigning. He’s never stopped campaigning. The US is forever changed. But here’s the thing. The Dems are also to blame. I was working with undocumented immigrants in the early 2000’s under Obama and the system was a mess. He did nothing to make it better. So the pressure kept building. And Biden’s 4 years did little too. By the time the Dems tried to pass real border reform they had lost control of Congress and Trump influenced from the sidelines and made sure it didn’t pass so he would win. It never should have gone that far. The Dems have blame in this game too. And from the looks of things I don’t see that we’ve learned a damn thing. Watch. Unless the Dems have changed we’ll see them screw up the messaging war on the government shut down and they’ll be hated even more by voters. MAGA would turn this closure into campaign gold if they were in the minority. Scary times.

We no longer have an unbiased Supreme Court. They are 100% ignoring settled law and diving deep into far right territory. It’s perhaps the biggest disappointment, disgrace, embarrassment and incompetence being perpetrated by what should be the greatest court in the world.