The Politics of Obamacare

How America’s most hated law became too popular to kill

When President Barack Obama rose to the podium in the East Room of the White House on March 23, 2010, the air crackled with anticipation. Lawmakers, advocates, and cameras packed the room as he prepared to sign the most sweeping health care reform in nearly half a century. “Today… health insurance reform becomes law in the United States of America,” he declared, casting the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act — colloquially known as Obamacare — as both a historic promise kept and a moral reckoning finally met.

As the president uncapped his pen to sign what would be his administration’s defining legislative achievement, Vice President Joe Biden leaned in to Obama’s ear and whispered, not at all quietly, “This is a big f***ing deal.” Cameras caught it; microphones amplified it; the line instantly entered political lore. Biden meant that the bill finally delivered on decades of bipartisan promises and repeated failures — from Harry Truman to Bill Clinton — to secure affordable care for millions of Americans.

But his words proved prophetic in ways no one fully appreciated. The law he celebrated would soon detonate American politics: fueling a nationwide backlash, costing Obama and Democrats their congressional majorities, galvanizing a Republican Party into near-religious opposition, and launching decade-long wars over not only the future of health care but the role of government itself in America.

In the years that followed, Obamacare would be sued, sabotaged, demonized, and nearly repealed — and yet never dismantled. Instead, through bitter fights and unlikely alliances, the Affordable Care Act quietly survived, expanded, and then did the unthinkable:

It transformed from America’s most-hated law into one too popular to kill. Even for Republicans.

Conservative roots of a liberal law

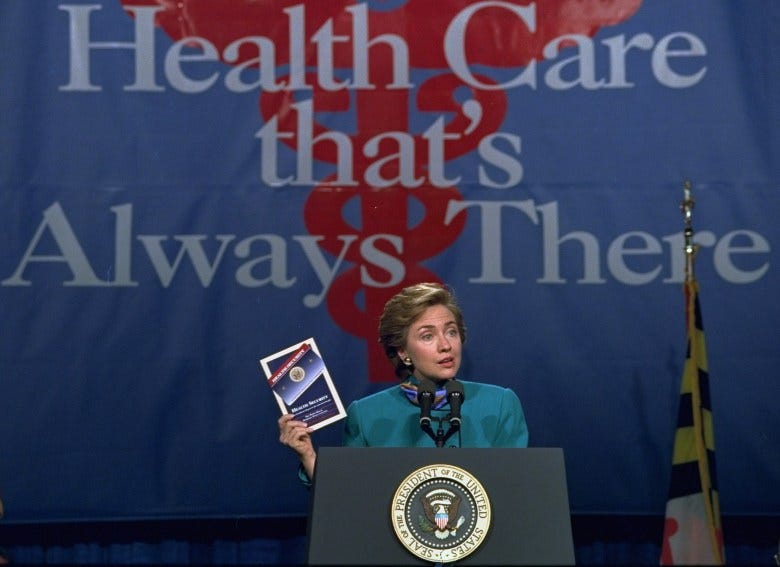

When Barack Obama entered office in 2009, health care reform wasn’t a Democratic flight of fancy — it was an old, bipartisan promise. For decades, presidents from both parties had vowed to fix an expensive, uneven system in which medical crises routinely bankrupted families. Bill Clinton tried to deliver, empowering First Lady Hillary Clinton to craft a plan for universal coverage in 1993. But “Hillarycare” collapsed under the weight of congressional resistance, industry opposition, and strategic missteps — including a secretive drafting process that fed public distrust. The defeat was so punishing that Democrats lost control of Congress for the first time in 40 years in the 1994 midterms.

That failure loomed large over Obama’s team. Advisers warned him not to repeat the Clintons’ mistake: a sweeping health overhaul could consume his presidency and derail the rest of his agenda. Obama was aware of how Hillarycare’s failure hampered Clinton’s first term, but he wasn’t willing to give up entirely. Instead, he took a different path: rather than design a new federal program, he embraced a market-based approach drawn directly from conservative thinking.

The backbone of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was built on a framework pioneered not by a Democrat but by a Republican: Mitt Romney. As governor of Massachusetts, Romney had signed a 2006 law built around private insurance marketplaces, subsidies for those who needed help buying coverage, and — crucially — an individual mandate requiring everyone to carry insurance. It worked: Massachusetts’s uninsured rate plunged to below 5% by the time Obama took office. Romney himself called the plan “a Republican way of reforming the market.”

This was no accident. The individual mandate — later a crux of GOP opposition — had originated not on the left, but at the conservative Heritage Foundation as early as 1989, proposed as a personal-responsibility alternative to single-payer health care. In 1993, Republican senators — including Minority Leader Bob Dole — introduced bills built around the mandate to counter the Clinton plan.

Obama adopted much of that framework. His health care blueprint rested on three pillars:

The individual mandate — requiring Americans to obtain coverage to broaden the insurance pool and keep premiums low;

Subsidies — federal tax credits to help lower- and middle-income families buy private plans;

Market reforms — including bans on denying coverage for preexisting conditions and caps on out-of-pocket costs.

It was, by design, a capitalist approach to social policy — strengthening private markets rather than replacing them.

The backlash that helped rebuild the GOP

At first, bipartisan cooperation seemed possible. Sens. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and Olympia Snowe (R-ME) joined negotiations, and moderate Democrats like Max Baucus (MT) crafted legislation in consultation with insurers and hospitals.

But by mid-2009, the politics shifted dramatically. The individual mandate — once a Republican idea — became the GOP’s rallying cry against the bill, and against Obama more generally. It offered a simple, potent talking point: the government is forcing you to buy insurance.

That message helped ignite the Tea Party movement — a populist, anti-tax, anti-government wave that exploded in the summer of 2009. Town hall meetings turned confrontational, protest signs warned of socialism, and the ACA became a stand-in for broader fears about an expanding federal government.

As the base radicalized, Republican lawmakers faced enormous pressure to abandon negotiations. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell later acknowledged that Republicans unified to deny Obama bipartisan policy victories. Sen. Jim DeMint (R-SC) was more explicit: “If we’re able to stop Obama on this, it will be his Waterloo — it will break him.”

Any hope of Republican support vanished. And yet, in March 2010, after more than a year of negotiations, over 100 separate committee hearings, over 150 hours of Senate debate, and more than 200 votes in Congress, the ACA passed without a single Republican member of Congress supporting the legislation. A bill built on conservative architecture had become a purely Democratic achievement.

Among other provisions in its 1,990 pages, the final law included:

Private insurance marketplaces (exchanges): online platforms where people can compare and buy private health plans.

Tax credits to help individuals purchase plans: federal subsidies that lower monthly premiums based on income.

Medicaid expansion (state option): allowed states to extend Medicaid to more low-income adults.

Consumer protections (preexisting condition ban, essential benefits, out-of-pocket caps): prevented insurance discrimination and required standard minimum coverage.

Employer mandate: required large employers to offer affordable health insurance or pay penalties.

Individual mandate: required most people to have coverage or pay a tax penalty.

Once the Affordable Care Act became law, the political battlefield widened. Republicans framed the statute not as a market-based reform built on conservative principles, but as a symbol of federal intrusion. The phrase “government takeover of health care” — later named PolitiFact’s 2010 Lie of the Year — saturated the airwaves and stuck.

This framing worked. Even as most Americans supported specific provisions of the law, public opinion turned sharply against “Obamacare.” A March 2010 Kaiser Health Tracking Poll found that while over 70% of Americans supported keeping young adults on their parents’ plans and banning insurers from denying coverage for preexisting conditions, only about 40% viewed the ACA favorably overall. In other words: people liked what was in the law but hated the idea of it.

The political costs were immediate. In the 2010 midterms, voters rebuked Democrats with historic force. The party lost 63 House seats, flipping control of the chamber; it was the worst midterm performance for a president’s party since 1938. President Obama acknowledged, “We took a shellacking.”

Republican leaders read the results as a mandate of their own: repeal. “Repeal and replace” became not just a slogan but the organizing principle of GOP politics for the next decade.

Obamacare on trial

Then came the implementation nightmare. In October 2013, the administration launched healthcare.gov — the federal online marketplace meant to showcase the ACA’s private-insurance model. Instead, it became a punchline. Servers crashed, pages froze, and on day one only six Americans successfully enrolled nationwide.

The debacle fueled the GOP narrative that Democrats could not competently administer the sweeping program they had forced upon the country. For Republicans, it was proof that health care was too complex for government to manage; for Democrats, it was a self-inflicted wound at the worst possible moment.

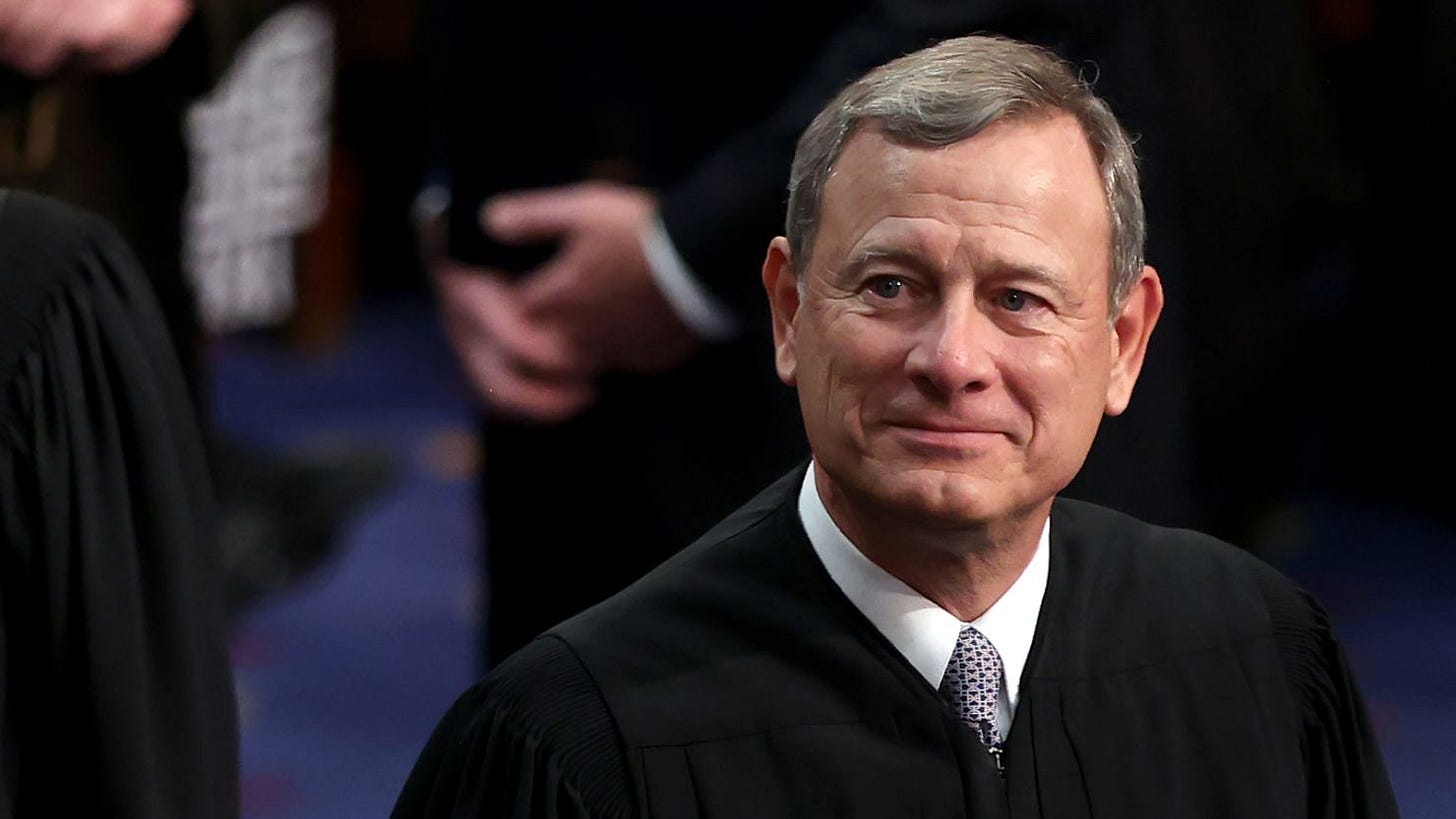

The fight quickly moved to the courts. Opponents challenged the ACA’s constitutionality, culminating in the 2012 Supreme Court case National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius. In a stunning decision, Chief Justice John Roberts joined the Court’s four liberals to uphold most of the law, including the individual mandate, by interpreting the penalty as a tax. The ruling shocked both parties — but it ensured the ACA would remain, as Obama put it, “the law of the land.”

But survival did not mean acceptance. The Court’s decision kept the ACA intact, yet the political war raged on. Republicans vowed to continue the fight through Congress, the courts, and the ballot box.

And soon, a new political figure would arrive on the national stage, promising to do what the Court would not: make sure Obamacare would no longer be the law of the land.

The evolving politics of Obamacare

When Donald Trump descended the escalator in 2015 and launched his presidential campaign, one of his core promises was to finally “repeal and replace Obamacare.” He called the Affordable Care Act “the worst health care law ever passed in this country” and promised a new system that would deliver “something terrific.” Once in office, Trump elevated the ACA to a litmus test of conservative credibility — a symbolic battle over federal power, national identity, and who deserved help from government.

But Trump was fighting against a different ACA from the one passed in 2010.

By the mid-2010s, the law had begun to quietly reshape the country’s health care. The uninsured rate fell from about 16% in 2010 to roughly 9% by 2015, the largest coverage expansion since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid. Tens of millions gained coverage through Medicaid expansion and subsidized private plans, and protections for preexisting conditions became foundational to the public’s expectations of health care.

Americans noticed. And they (mostly) liked it.

By the time Trump was sworn in in 2017, Pew found that 56% of Americans approved of the ACA, with nearly half of the country saying the law had a positive rather than negative impact on the country; a big deal on such a polarized issue. Perception of the law had flipped: provisions once abstract had become personal, tangible, and valued.

This created a tough dynamic for Republicans. They had spent years promising to repeal the ACA. Many had run campaigns on that single commitment. But now millions of their own constituents depended on it. Repeal was no longer a cost-free symbolic vote — it meant stripping insurance from families who couldn’t afford to lose it. (This didn’t at all prevent the GOP-controlled House from spending 378 hours on over 50 votes to repeal the ACA that went nowhere).

In July 2017, that tension exploded in public view. The clock ticked toward a dramatic midnight vote in the Senate on a “skinny repeal” bill designed to gut core ACA provisions with nothing to replace them. Even some Republicans admitted privately they expected the plan to fail — they had no consensus alternative, and the Congressional Budget Office projected 17 million Americans would lose their coverage.

In the end, the bill died with a single, dramatic thumbs-down from Sen. John McCain (R-AZ), who said Congress “must now return to regular order” and craft bipartisan solutions. The chamber gasped; the ACA survived.

The moment revealed a fundamental truth of social policy: once government gives people a benefit — especially one as intimate as health care — it becomes nearly impossible to take away.

For Republicans, the politics of repeal had backfired. The ACA had evolved from a polarizing law into a program with a constituency — one that included millions of rural, white, and older Americans who formed the backbone of the GOP coalition. Repealing the ACA now meant not just keeping a campaign promise but also ripping coverage from the very voters who had delivered Trump to power.

The law’s survival was no longer a question of judicial review or congressional arithmetic. It was now protected by something far more durable: people had gotten used to having health insurance. They didn’t want to lose it.

And suddenly, a once-hated law had become too popular to kill — even for the party that won political power on a promise to bury it.

At the center of the government shutdown

When Joe Biden took office in 2021, his approach to the ACA was a departure from the defiant repeal efforts of his predecessor. Instead of dismantling the law, he aimed to strengthen it. His administration boosted marketplace subsidies, expanded outreach to uninsured Americans, and worked to stabilize insurance markets. Meanwhile, the ripple effects of the Trump years remained visible: coverage gains, marketplace enrollments, and a growing constituency for the law.

At the conclusion of Biden’s term, more than 24 million Americans relied on ACA marketplace subsidies, and 64% of US adults held a favorable view of the ACA while just 35% viewed it unfavorably.

It wasn’t just Democrats who embraced the ACA’s gains. Some Republican governors in Medicaid-expansion states began publicly defending its core protections and affordability subsidies. A law once opposed as arrogance had become, in practice, indispensable.

That brings us to the present standoff: the 2025 government shutdown, now in large part a battle over the ACA’s premium tax credits. The subsidies — expanded during the Covid-19 relief era — were set to expire at year’s end, and Democrats demanded their renewal as a condition of funding the government. Republicans, while theoretically open to extension, insisted that such changes be tied to broader spending cuts and budget bills. Democrats, without many leverage points in DC, decided to tie their votes for government funding to the subsidies. And the result was the government shutdown.

Even some hard-line Republicans expressed concern about neglecting to extend the subsidies. In Georgia, for example, GOP Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, traditionally a Trump loyalist, sounded the alarm about expiring ACA subsidies, warning of premium spikes and coverage losses in her conservative-leaning district. Meanwhile, insurers and marketplace managers projected that without the credits, premiums could triple for many enrollees — triggering voter outrage and threatening the political coalition that powered Trump’s rise.

Most Republican lawmakers still criticize the ACA — often on ideological grounds, often as a symbol of federal overreach. But 15 years after its enactment, the party remains united in criticizing Obamacare as an abstract law without offering any real alternative to it. Repeal is no longer a credible rallying cry. Behind the rhetoric lies a hard political reality: changing the law — especially cutting subsidies — would mean real, immediate costs for millions of voters, including many in deeply conservative districts.

That recognition is shaping the current shutdown fight. While Republicans have not embraced the ACA, they have grown markedly more cautious about dismantling it outright. Lawmakers understand the electoral vulnerability in taking health coverage or financial assistance away from their constituents, particularly in rural states that have benefited most from Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies. The politics have reversed: where Obamacare was once seen as a liability for Democrats, today it is Republicans who risk backlash if they push too far.

And so the law endures — still debated, still resented in some quarters, still imperfect. But also deeply woven into the country it remade.

This was very interesting. I had no idea Obama used framework from Republican ideas

A perfect example of how emotional and childish our political landscape is.