The 1898 Coup America Forgot

It delivered schools, voting rights, and Black representation. White elites responded with an armed coup.

For the friend or family member who lives far away, skip the scarf they don’t need. Give them something that shows up every week — a gift that reminds them you’re thinking of them, no matter the distance. Gift a whole year of unlimited access to The Preamble now.

The 1898 Coup America Forgot

When President Biden promised to nominate a Black woman to the Supreme Court, it sparked a fierce debate over qualifications and quotas. One claim was that intentionally seeking to increase diversity — especially in this way — must come at the expense of finding the most qualified candidate. This line of thinking has been weaponized to delegitimize the very presence of people from marginalized identities who serve in positions of power. Conservatives have framed institutional initiatives to promote diversity in electoral politics and higher education as a threat to “excellence.” Pete Hegseth famously called the phrase “Our diversity is our strength” the “single dumbest phrase in military history.”

Then you have the backlash against rising political figures like New York mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani, who has faced what he called “racist, baseless attacks” and Islamophobia. These attacks often weaponize his identity as a Muslim to cast him as inherently unfit for leadership. We saw this also play out over an entire presidential tenure with the “birther” campaign against Barack Obama, which questioned his American citizenship and eligibility for the presidency.

It’s no coincidence that this toxic playbook surfaces whenever a multiracial political coalition gains power.

The current hand-wringing over DEI and “identity politics” echoes circumstances in the late 19th century surrounding the first alliance in US electoral politics between people of different races. This alliance in North Carolina, known as Fusion politics, actually achieved success and threatened to fundamentally dismantle the Southern racial hierarchy. We must understand how the Fusion movement was violently and deliberately destroyed in an antidemocratic coup, because that blueprint for political insurgency still shapes the world we live in today and may predict where we are headed.

North Carolina in 1898

After Reconstruction, the Democratic Party in the state had established an insidious form of political control. They maintained power through the County Government Act of 1877, a law that effectively allowed the Democratic legislature to appoint county commissioners and judges, thus controlling local governments and preventing Black citizens and Republicans from gaining local power in these non-elected positions. Meanwhile, poor farmers — both Black and white — were drowning in debt due to currency deflation and an economic depression. Wealthy political elites maintained control by dividing the working class along racial lines.

But in the 1890s, the Populist Party emerged, driven mainly by the interests of those struggling agriculturalists. The Populists, mostly white commercial farmers, realized they had more in common with the Black voters who were largely aligned with the Republican Party than they did with the wealthy white Democratic elites who were actively harming their livelihoods.

Enter Marion Butler, the Populist leader. Butler was an incredibly influential figure, a leading agriculturalist who had risen to become the powerful state chairman of the Populist Party and the editor of its newspaper, The Caucasian. He was a man who understood both the plight of the dirt-poor farmer and the mechanics of statewide political organizing. His thinking was simple: unite or be ruled.

Through secret meetings with Black and white Republican leaders, Butler engineered an agreement. They hammered out a deal and organized a strategic alliance — a joint electoral ticket. In their fear, Democrats derisively labeled them “Fusionists.” This strategic partnership, born of necessity and economic desperation, would eventually propel Butler himself to the US Senate.

In 1894, the Fusion alliance of Populists and Republicans swept elections across the state. The “Fusion wave” gave them control of the State Legislature, several seats in the US House of Representatives, and even the state’s supreme court, ensuring the Democrats were locked entirely out of power.

The Panic of White Elites

When this diverse coalition finally took power, they governed in a way that truly democratized the state.

Unsurprisingly, their first order of business was to dismantle the machinery of Democratic control. They repealed the suffocating County Government Act of 1877, restoring county home rule. They increased funding for public education and social institutions. They also liberalized access to the ballot, a move that increased registered voters by over 80,000, in part by ensuring that all political parties were represented by election judges at the polls and by requiring colored and distinctive party insignia on ballots so that even illiterate citizens could vote for whom they wanted.

Fusionists won an even larger victory in 1896, electing Republican Daniel L. Russell as governor and taking control of virtually all statewide offices. For the first time since Reconstruction, the Democrats were entirely out of power.

Crucially, this alliance resulted in a dramatic, visible increase in political diversity. There were approximately 1,000 elected or appointed Black officials serving under Fusion rule, including US Congressman George H. White. To the white Democratic elites who had clung to power through race-based division, this vibrant, effective, multiracial democracy was a horrifying spectacle.

They decided to respond with a campaign that, by its very design, was a declaration of war against the concept of equality.

The White Supremacy Campaign

The Democrats, led by Furnifold M. Simmons, decided in 1898 that their winning strategy would be to abandon all pretense of policy debate and focus entirely on a single idea: white supremacy.

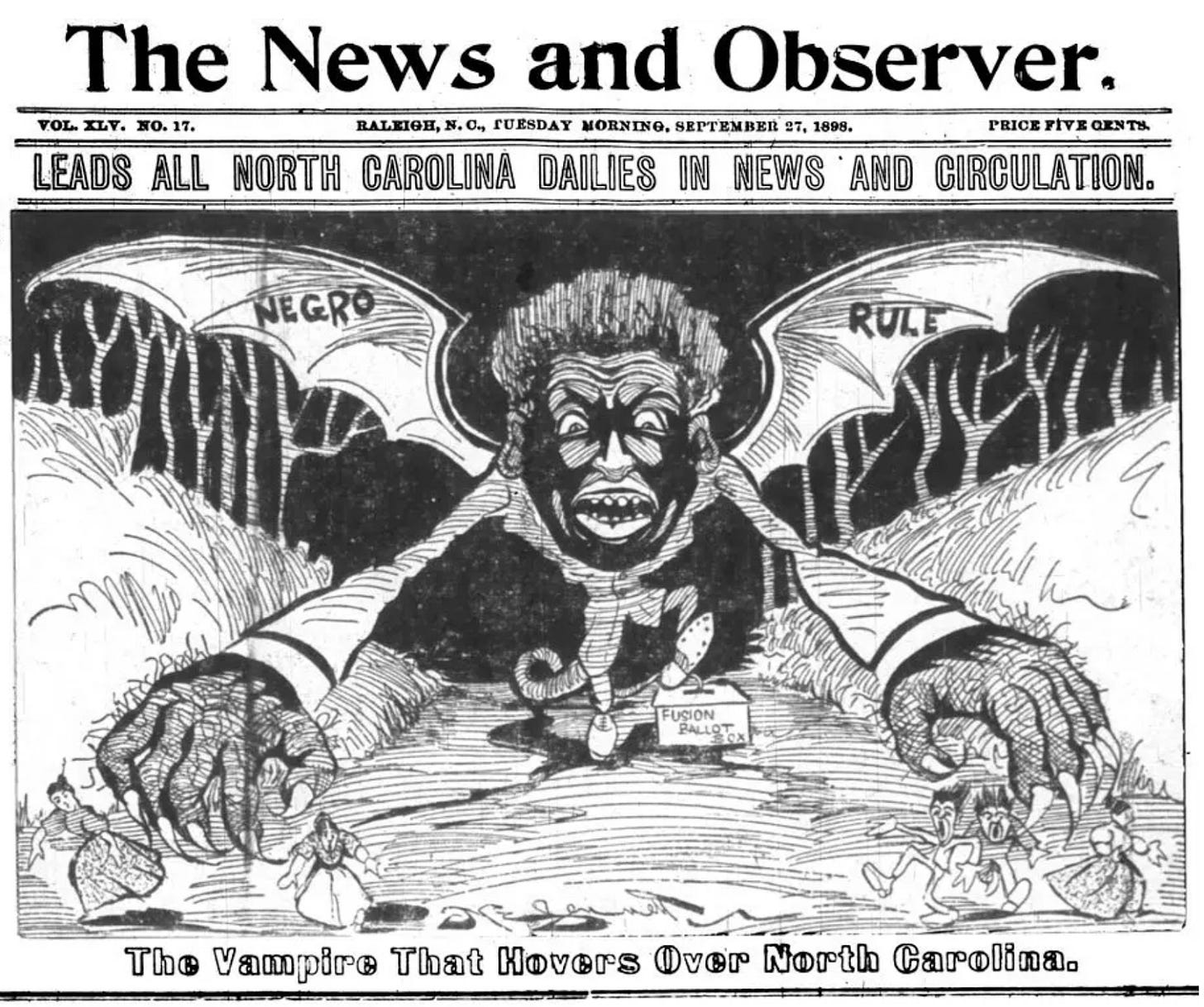

This was “identity politics,” stripped of any pretense of inclusion and class solidarity, deployed as a weapon of political terror. The catchphrases “Negro rule” and “Negro domination” were plastered everywhere, fueled by the propaganda of press spokesman Josephus Daniels, editor of The Raleigh News and Observer. This was a coordinated, three-pronged attack executed by “Men Who Could Write” (propaganda via newspapers), “Men Who Could Speak” (Democratic orators), and “Men Who Could Ride” (terrorist groups like the Red Shirts, a paramilitary wing of the Democratic Party).

Daniels himself spearheaded a propaganda effort that incited white citizens into a furor, using sexualized images of Black men and their supposedly uncontrollable lust for white women. Newspaper stories and stump speeches warned of “black beasts” who threatened “Southern womanhood.” The visual hate was visceral: Daniels’ newspaper published a caricature of a huge vampire bat with “Negro rule” inscribed on its wings, and white women and men beneath its claws, captioned “The Vampire That Hovers Over North Carolina.”

They leveraged a statewide campaign of stump speakers, torchlight parades, and physical intimidation. Charles B. Aycock, who later became the state’s governor, earned his prominence through fiery speeches for white supremacy. Meanwhile, the Red Shirts thundered across the state on horseback, disrupting African-American church services and Republican meetings. The explicit goal was to keep Black North Carolinians away from the polls by any means necessary.

Congressman W. W. Kitchin, an avid white supremacist, publicly declared, “Before we allow the Negroes to control this state as they do now, we will kill enough of them that there will not be enough left to bury them.”

The goal was to weaponize race to destroy the working-class solidarity of the Fusionists. And it worked. The Democrats won on the state level in November 1898, riding a wave of fear, intimidation, and violence that targeted Black voters and white Populist allies alike.

But one city, a majority-Black port town, still stood in defiance: Wilmington. Fusionists still ran their government.

The Insurrection

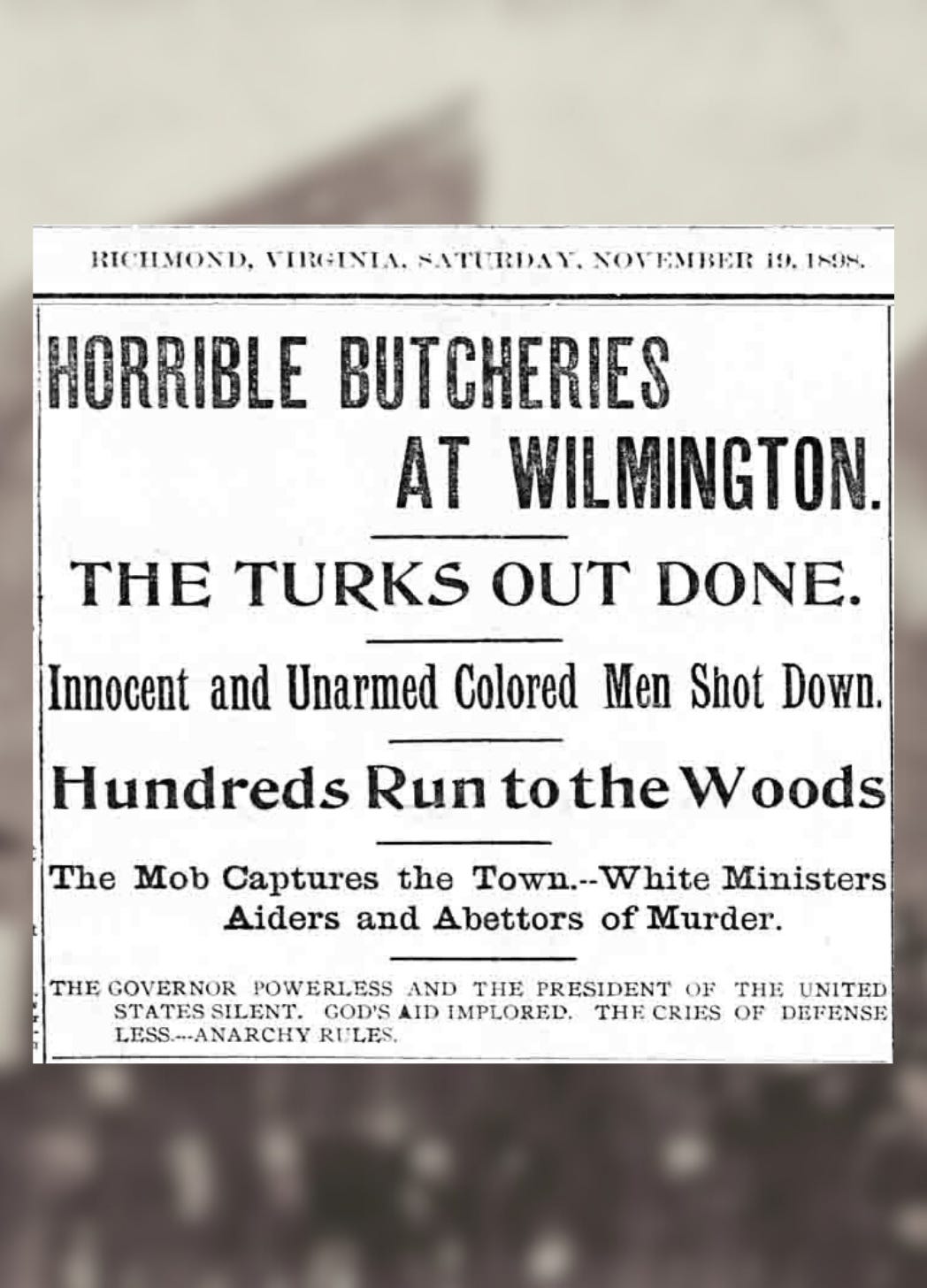

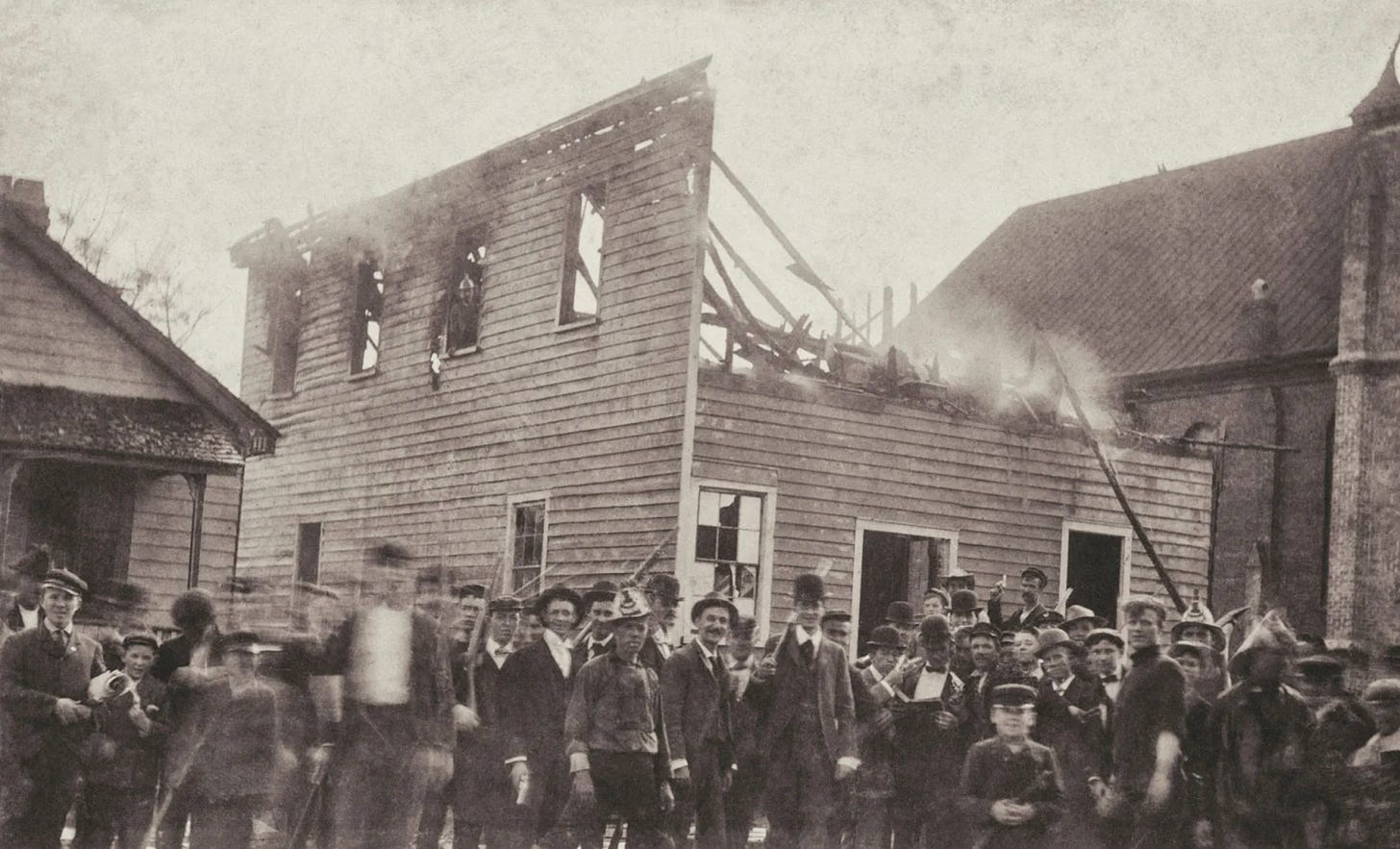

Two days after the state election, on November 10, 1898, the local Democratic leadership, known as the “Secret Nine,” decided to overturn the government without an election. What followed is now correctly referred to as the Wilmington Coup d’État (or Wilmington Massacre).

An armed mob, composed of what one witness described as “well-ordered” columns of white men, marched military-fashion into the Black neighborhoods of Wilmington. The result was a horrific, coordinated attack, with Red Shirts and other white vigilantes romping through the Black sections of town to “kill every damn nigger in sight,” as one of them put it. The attack left between 14 (the official count) and 300 Black people murdered.

While the streets became a killing ground, the city’s power structure was simultaneously being overthrown. White leaders launched a coup d’état at City Hall, forcing the mayor, the board of aldermen, and the police chief to resign at gunpoint. Within hours, the white Democrats literally installed their own government, replacing the elected Fusionist officials with their hand-picked white appointees. Having seized power, they then banished at least 21 successful Black citizens and their white allies from the city. The Fusionist movement was utterly destroyed. It would take nearly 70 years for meaningful multiracial political participation to occur in North Carolina after the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

What we can take away from this

When you hear today’s arguments against DEI or political representation for marginalized groups, or listen to the outrage over a mayoral candidate’s identity, you are hearing the modern iteration of the 1898 white supremacy campaign.

The old Democrats didn’t argue that Fusionists had bad policy — they argued that the very existence of a government where Black citizens held meaningful power was an existential threat. They used identity (Black rule) as a scare tactic to override policy (debt relief, education funding) and convince poor white people to vote against their own economic interests. They succeeded by replacing the fear of debt with the primal fear of the “other.”

This tactic persists with alarming success today. Consider the viral claim from last year’s election cycle about Haitian immigrants in Ohio eating pets. City officials confirmed there were “no credible reports” of such acts, yet the story was amplified across social media as a symbol of the grave dangers posed by “uncontrolled” immigration. Ironically enough, the playbook has been used by Republicans against other Republicans who don’t fit a specific mold.

Former Republican presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy has been repeatedly and publicly confronted over his Hindu faith by audience members who questioned how his religion “fits into the US.” One individual accused Hinduism of being a “wicked, pagan religion” and asserted that the Founders based the country solely on Christianity. The message in both cases is identical to that in 1898: your identity makes you inherently unfit to participate.

The Wilmington coup d’état serves as a horrifying yet illuminating example of what happens when a powerful, entrenched elite sees its political power slipping due to genuine cross-racial solidarity. It shows us that the fight today (and back then) isn’t just about different policy priorities; it’s about whether the diverse democracy the Fusionists created — and the white supremacists destroyed — will ever be fully realized. They may not have fire and Red Shirts today, but the media outrage, the targeted attacks, and the relentless framing of inclusion as a “threat” are just as recognizable.

I was born and raised in Wilmington. I was 50 years old when I learned of the Wilmington Massacre. It was erased from classrooms. The story was shared with me by a childhood friend and I began asking others if they knew about. None of us were taught this history in elementary in the 1970s.

How was this possible you ask? Our current administration is working to do the same to many parts of our history. This is such an important story to tell.

Thank you for writing this article. I had never heard of this coup in 1898. And I agree with your sentiment about what is happening now.