Rallies and Marches Aren’t the Only Way to Protest

Many successful moments of activism have happened off the streets

The United States has always been a protest nation. Long before it was a country, collective action was how political demands were made visible. The Boston Tea Party wasn’t a riot; it was a coordinated act of economic disruption aimed at a distant governing authority. The Declaration of Independence itself was, at heart, a formalized protest letter — an itemized list of grievances addressed to a king whose legitimacy the authors no longer recognized.

That lineage mattered enough to be written into the Constitution. The First Amendment didn’t just protect speech or religion; it explicitly safeguarded the right of the people to assemble and to petition the government for redress of grievances. Protest was not treated as a nuisance to governance. It was recognized as part of it, an essential feature of what it meant to be a citizen in a republic rather than a subject in an empire.

American history is thick with examples of that tradition in action. Abolitionists organized boycotts and petitions that reshaped national debate long before the Civil War. The labor movement relied on strikes and walkouts to force concessions that later became law. The Civil Rights Movement paired marches with sit-ins, court challenges, voter-registration drives, and sustained economic pressure (think Birmingham, Selma, Greensboro) — tactics that made segregation not just immoral but untenable. Protest has never been only about visibility. It has always been about leverage.

That spirit is still alive. From demonstrations against immigration enforcement to protests over policing, abortion, climate policy, and foreign wars, Americans continue to show up in the streets.

And yet a familiar frustration hangs over many of these moments: What does any of this actually change? Protest feels most powerful when it is visible, but visibility alone rarely forces change. Marches are cathartic but fleeting. Outrage burns hot and then disappears. The systems people are protesting seem unmoved. It’s natural to wonder what kinds of protest have actually worked in practice — especially in our modern era of hyperpartisan politics.

The answer is that many of the most successful pressure campaigns have not centered on mass marches at all. They’ve relied on boycotts, sit-ins, coordinated calls and letters, targeted walkouts, regulatory complaints, procurement threats, shareholder pressure, and innovative forms of digital activism. Different tactics. Different targets. Different outcomes.

The case studies that follow aren’t from the history books — they are from the last dozen years. And they show how organizers identified leverage points, coordinated action, and translated moral claims into consequences decision-makers could not ignore.

The lesson isn’t that protest is futile. It’s that protest works best when it is designed, not just expressed — and that there is more than one way to do it.

How Seattle’s $15 minimum wage actually happened

In the fall of 2013, a little-known economics professor named Kshama Sawant shocked Seattle politics. Running as an open democratic socialist, Sawant won a seat on the Seattle city council on a blunt promise: raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour — no compromises, no phase-ins designed by corporations.

At the time, $15 wasn’t a mainstream policy demand. President Obama was calling for $10.10. Business groups warned of job losses. Even progressive Democrats in Seattle treated $15 as aspirational rhetoric, not an actionable policy.

Sawant and her allies didn’t “raise awareness.” They set a deadline — and dared City Hall to stop them.

The organizing backbone was a coalition led by 15 Now (an advocacy group founded by Sawant), fast-food workers backed by the Service Employees International Union, and community groups already mobilized around housing and racial equity. Their strategy was not symbolic protest — it was procedural pressure toward a very specific end.

First, they threatened a ballot initiative and sent a clear message to the council — pass $15 or we’ll pass it without you. As activists gathered signatures, Seattle’s political class understood that a citywide vote could pass — and that losing control of the policy would likely mean an immediate jump to $15, applied across all employers, rather than a more gradual phase-in and exemptions for smaller businesses.

Second, the coalition staged targeted walkouts that made the problem visible at the exact places people felt it. Fast-food workers left their shifts together at the same chains and job sites, on the same days. Walkouts were timed to peak hours and paired with press, signage, and spokespeople who could explain the ask in a few words: wages that didn’t require workers to have food stamps to survive.

Third, they occupied City Hall selectively. Instead of mass marches every weekend, organizers flooded council hearings, committee meetings, and mayoral events with workers who had one request only: $15 an hour. Fast-food workers and airport employees showed up to testify by name, with pay stubs, describing wages that were inadequate without public assistance.

Mayor Ed Murray eventually convened a business–labor task force to show action on the issue without actually committing to pushing for the wage hike. Organizers used it anyway — feeding worker testimony to the press while refusing to treat the task force as the final authority.

The result: in June 2014, Seattle passed the nation’s first $15 minimum wage law. Large employers had to comply by 2017; smaller ones were phased in later. The policy raised wages for more than 100,000 workers.

Why it worked: Organizers combined a credible ballot threat with focused disruption and disciplined messaging, forcing city leaders to choose between passing $15 themselves or losing control of the policy — and facing a harsher outcome.

The bathroom bill that got beaten by accountants (North Carolina’s HB2)

In December 2016, North Carolina Governor Pat McCrory called a surprise special session of the state’s legislature after Charlotte expanded local nondiscrimination protections (including those for LGBTQ residents).

In less than a day, legislative leaders Tim Moore and Phil Berger moved a bill through both chambers. McCrory signed it that night.

The law did two things that mattered to pressure-campaigners:

It required people in government buildings to use bathrooms tied to sex on a birth certificate; and

It wiped out local nondiscrimination rules and blocked cities from restoring them.

The public backlash was loud. The campaign that changed the political math was legible.

Instead of arguing about culture and morals, opponents translated the law into an invoice — lost jobs, lost events, lost investment — and made state leaders wear it.

First came corporate noes with numbers attached. PayPal’s CEO, Dan Schulman, scrapped a planned expansion in Charlotte, explicitly citing the law. Other firms followed with their own versions of the same message: we’re not growing here while this is on the books. One study estimated the “bathroom bill” would cost the state nearly $4 billion.

Then came sports organizations treating the state as a risk. The National Basketball Association didn’t just condemn HB2 — it yanked the 2017 All-Star Game out of Charlotte after months of warnings. That wasn’t merely symbolism; it was a national broadcast pulled, hotel nights erased, sponsors spooked, and the state law becoming a national conversation. North Carolina lost out on an estimated $100 million that the All-Star Game would have pumped into its economy.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association escalated the same way: it relocated multiple championship events that were already scheduled for North Carolina, with NCAA president Mark Emmert framing the decision as the only one that could provide a “safe and inclusive environment” for student-athletes.

That’s when the accountants showed up.

Chambers of commerce, tourism boards, university administrators, and event planners weren’t debating ideology — they were pricing reputational damage, uncertainty, and especially economic hits to their local economies. The argument legislators could ignore on cable news became harder to ignore in budget meetings and boardrooms.

The result wasn’t instant purity. It was movement under measurable economic and political strain.

By March 2017, a new governor, Roy Cooper, signed a compromise measure (HB142) that repealed key pieces of HB2 while still drawing criticism from both sides. But the economic signals mattered, with the NCAA lifting its hosting ban after that partial repeal.

Why it worked: The campaign didn’t just shame decision-makers — it made the law expensive in the currency that power understands (events, investment, jobs, and reputational risk), and it kept the pressure coordinated long enough that leaders had to choose between “winning the culture war” and ruining the balance sheet.

Ending campus sexual violence: the protest that ran through Title IX paperwork

The turning point wasn’t a march. It was a file upload.

In 2013, two University of North Carolina students, Annie Clark and Andrea Pino, did something most people don’t realize was a protest tactic: they filed a federal Title IX complaint arguing that their school had mishandled hundreds of sexual-violence reports.

They weren’t just telling their story. They were pulling the federal alarm — a complaint to the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) forces a university to provide formal, written answers on the record, with the threat of federal dollars hanging overhead. At UNC, it moved sexual violence out of the realm of “messy controversy” and into the realm administrators fear most: enforceable exposure.

The regulatory lever was Title IX itself. The OCR’s guidance had already put schools on notice that sexual violence can be a form of sex discrimination and must be met with “prompt and equitable” responses. But activists turned that principle into a repeatable playbook: document, file, force a timeline, force accountability.

Students across the country followed their lead. Using their template, sexual assault suvivors and supporters filed hundreds of Title IX complaints at their respective institutions.

Then the Obama White House jumped in. The White House Council on Women and Girls created a dedicated task force and the “Not Alone” framework, which called on colleges to adopt clear procedures for responding to sexual assault, provide confidential support resources, and ensure sanctions for perpetrators. It pushed campuses to adopt live hearings, use trained investigators, set prompt timelines for adjudication, and publish annual reports on disciplinary outcomes so that students and families could see how cases were handled.

Later, when the Trump Education Department moved to unwind Obama-era guidance and rewrite the rules through a formal notice-and-comment process, the fight shifted to another underused arena: administrative rulemaking. Activists flooded the docket with submissions, built broad coalitions of students, civil-rights groups, and university administrators, and amplified the political cost of rollback. That tactic forced opponents to defend their positions not just in abstract debate but in a procedural forum where every submission, coalition letter, and public comment became part of the record — making the costs of dilution or repeal politically visible.

Why it worked: The campaign targeted a choke point decision-makers can’t ignore — federal compliance. You don’t need permission to march; you just need receipts, a template, and the willingness to turn personal harm into a regulatory record.

#DeleteUber: the boycott that lived inside people’s phones

In January 2017, as President Trump announced a travel ban that had the effect of blocking citizens of several Muslim-majority countries from entering the US, thousands of protesters converged on JFK Airport. New York taxi drivers staged a one-hour strike in solidarity with detained travelers. But Uber didn’t join the strike. Instead, the company turned off surge pricing near the airport and sent a notification signaling that rides were still available.

To critics, that wasn’t neutrality — it looked like strike-breaking dressed up as efficiency.

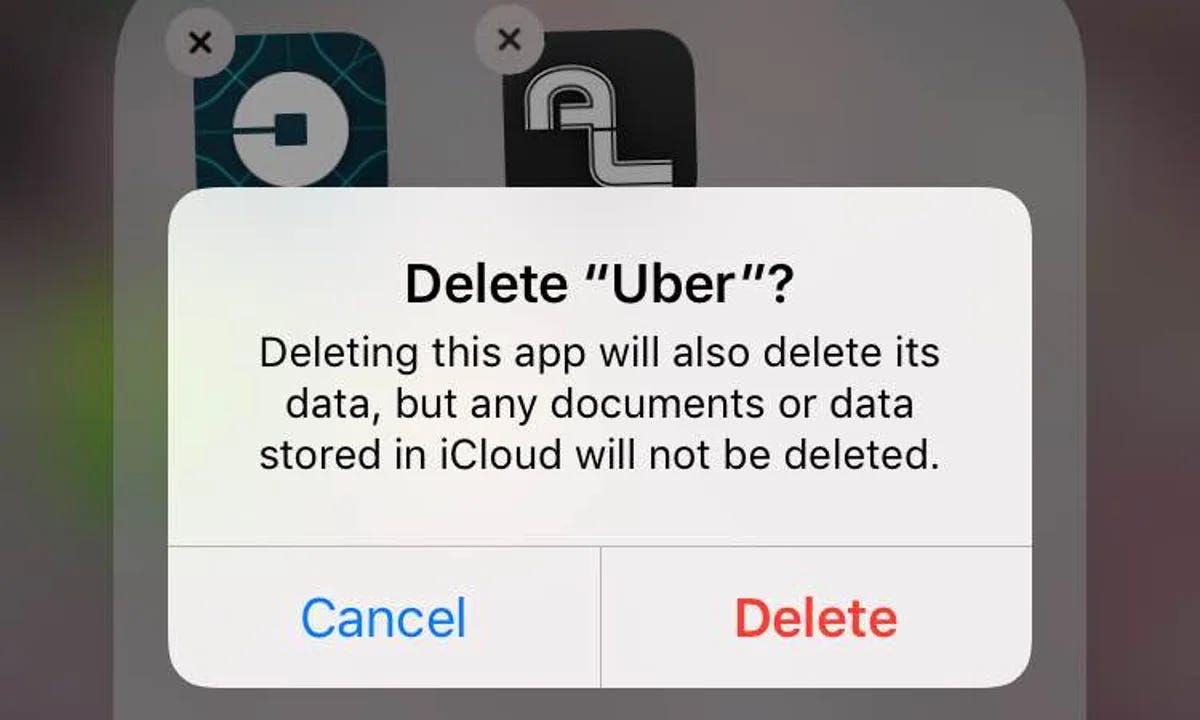

Within hours, a response crystallized around a single, brutally simple instruction: #DeleteUber.

The genius of the tactic wasn’t persuasion; it was design. Deleting Uber required no ongoing sacrifice, no long-term lifestyle change. It was a quick action that aligned moral outrage with muscle memory. The hashtag itself functioned as a simple how-to guide in that the message became a clear and simple call to action: delete Uber.

The pressure landed fast, and in multiple places at once.

First, users left. Uber reportedly lost hundreds of thousands of accounts in days. Competitor Lyft saw a surge in downloads of its app and publicly pledged a $1 million donation to the ACLU, further sharpening the contrast.

Second, employees revolted. Internal discussion channels at Uber lit up. Engineers and staff openly questioned leadership judgment and ethics. This wasn’t an external PR crisis alone — it became an internal legitimacy problem, the kind that spreads in companies dependent on talent retention.

Third, the boycott fused with preexisting scrutiny of Uber’s culture. Travis Kalanick, the company’s CEO, was already facing criticism over aggressive corporate practices such as launching into cities without permits and rewarding growth at almost any cost. At the same time, employees were raising alarms about a workplace where sexual harassment was tolerated, sexist language was commonplace, and HR complaints were mishandled, producing a reputation for internal misconduct that went beyond isolated incidents.

#DeleteUber didn’t create those problems; it synchronized them. What had been a series of isolated scandals snapped into a single narrative about leadership failure and values.

And then came the cascade.

By February, Uber announced — explicitly citing the controversy — that Kalanick would step down from President Trump’s business advisory council. Investigations into workplace culture accelerated. Board pressure intensified. By June 2017, Kalanick had resigned as CEO.

No law changed. No regulator acted first. No court issued an order.

What changed was Uber’s risk profile as the default ride-share app. The boycott attacked the company where it was most vulnerable: habit, reputation, and internal cohesion. When millions of people carry your business in their pockets, protest doesn’t need a march. It needs a tap.

Why it worked: The ask was minimal, the signal was public, and the consequences — user loss, employee dissent, and leadership instability — accumulated quickly, forcing accountability without the passage of a bill.

So… now what?

The lesson in all of this is that protest is broader than we’re often told. Change rarely comes from a single march or moment of visibility. It comes from pressure applied in the right places, sustained long enough to matter.

What these examples show is that ordinary people still have leverage. Sometimes it looks like a ballot threat. Sometimes it looks like a spreadsheet. Sometimes it’s a regulatory complaint, a boycott that spreads faster than a press release, or a coordinated effort that makes the status quo more expensive than reform. None of it requires permission. All of it requires intention.

That’s worth remembering in moments when frustration sets in. Collective action doesn’t fail because people care too much. It fails when energy isn’t paired with strategy. The good news is that strategy is learnable, adaptable, and contagious.

Protest has never been just about being seen. At its best, it’s about making power feel pressure. That tradition didn’t end with the Civil Rights Movement, and it isn’t waiting to be rediscovered. It’s already here — quietly, creatively, and effectively — wherever people decide that showing up is the first step, not the last.

Hope, it turns out, isn’t a feeling. It’s a method.

Yesterday, in KCMO, we pressured Platform Ventures into stopping their sale of a warehouse to ICE for a concentration camp. We made their corporate officers famous, we protested outside their offices, we shamed the local government entity (KC Port Authority) that gave them tax abatements on the building so much that they cancelled future business with them. We made the sale toxic on every level.

Of course, it’s not over. ICE will find another owner willing to sell to them. Rep. Mark Alford has publicly invited them to his neighboring county.

But we have a win. And winning is contagious. Because when we fight, we win!

I’d love to hear all of the ideas for the situation we’re in today.

After the inauguration, we canceled Amazon Prime. Turns out, it’s painless. If we MUST order something from Amazon, we can (I cannot tell you the last time it happened, though)…it just might take longer. It’s been a pleasure to get back out into the stores, especially supporting local businesses.