Why Washingtonians Live Without Democracy

“Our capital city has been overtaken by violent gangs and bloodthirsty criminals, roving mobs of wild youth, drugged-out maniacs, and homeless people,” President Trump announced last month. Crime is so out of control, he said, that immediate intervention was necessary.

He ordered several hundred National Guard troops to patrol the city and tried to put the Justice Department in direct command of DC’s police force before a federal judge ruled that the law prevented him from doing so. (Under an agreement between DC and the administration, the president instead “directed” the city’s mayor to use the police for federal purposes.)

DC has sued the federal government, claiming the National Guard deployment is a violation of the Posse Comitatus Act, which forbids the use of the military for domestic law enforcement. But for now, the troops remain in the city, their tactics — which include random checkpoints and masked federal agents aggressively detaining people suspected of immigration violations — continuing to antagonize Washingtonians.

How can a president wield such power, even over the objections of local elected officials and residents?

The narrow answer is that the District of Columbia Home Rule Act gives the president authority to direct the mayor’s policing decisions in the event of “special conditions of an emergency nature.” By declaring a crime “emergency,” the president claimed the authority he needed to intervene.

But the larger story has to do with DC’s unique legal status, its history, and a long tradition of federal politicians who meddled in city affairs — not because they had to, but because they could. Washingtonians are largely powerless to resist federal encroachment because, unlike other American citizens, they still suffer from the tyranny that America’s founders fought against: taxation without representation. It is long past time to end this injustice.

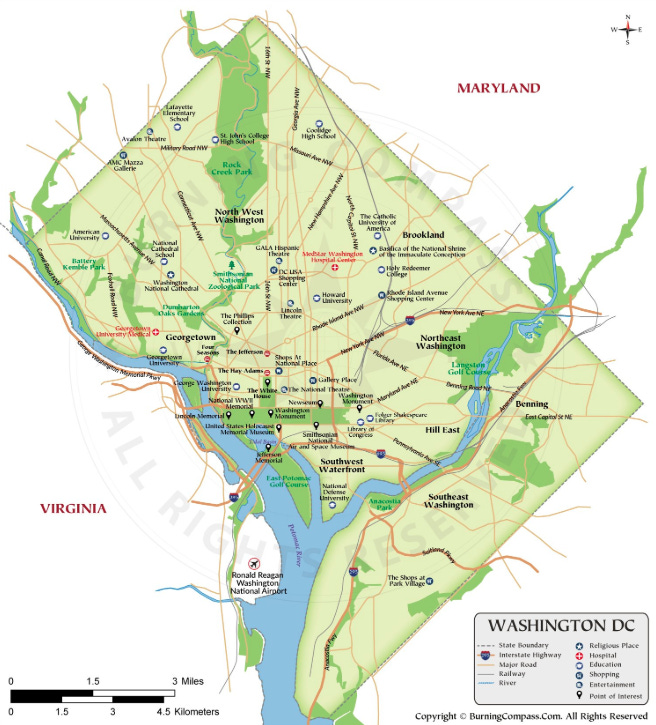

DC is a creature of the Constitution. Article I, Section 8, specifies that the seat of the federal government must reside in an independent “District” not controlled by any state. After a famous dinner table deal cut between Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton, the first Congress placed this new district on the shores of the Potomac River and named it in honor of George Washington and Christopher Columbus.

In the two centuries since, DC has grown into a cosmopolitan city. It is home not just to the federal government and flocks of summer interns, but also to more than 700,000 permanent residents — more people than live in Vermont or Wyoming. Many Washingtonians can trace their roots in the city back for generations.

DC has also become a stage for American democracy, a parade ground where we put our ideals on display for the world. And yet there is a profound irony at DC’s core. It is both the heart of the world’s oldest democracy and a city without democratic self-determination. It exists at the mercy of the federal government, forcing residents into a frustrating role as dependents who have no say in the federal laws that ultimately govern them.

Washingtonians elect a mayor and city council, and they can vote for president (thanks to the 23rd Amendment, ratified in 1961). But in Congress, all they have are a “Non-Voting Delegate” and a “Shadow Senator,” neither of whom can vote on legislation. DC residents pay more in federal taxes than 24 states, yet they have no representatives who can shape how those taxes are imposed. That’s why the line at the bottom of DC license plates reads, “End Taxation without Representation.”

Washingtonians were not originally so powerless. Under the original Constitution, they had the right to vote in federal elections, but it was stripped away in 1801 as members of the Federalist Party in Congress tried to centralize power in the national government.

Up until the 1870s, Congress did allow the city to have an elected mayor and Board of Aldermen. But that changed, too, after Black voters newly enfranchised during the post–Civil War Reconstruction period joined with white Radical Republicans to elect a biracial slate of local representatives, who passed remarkably modern anti-discrimination legislation.

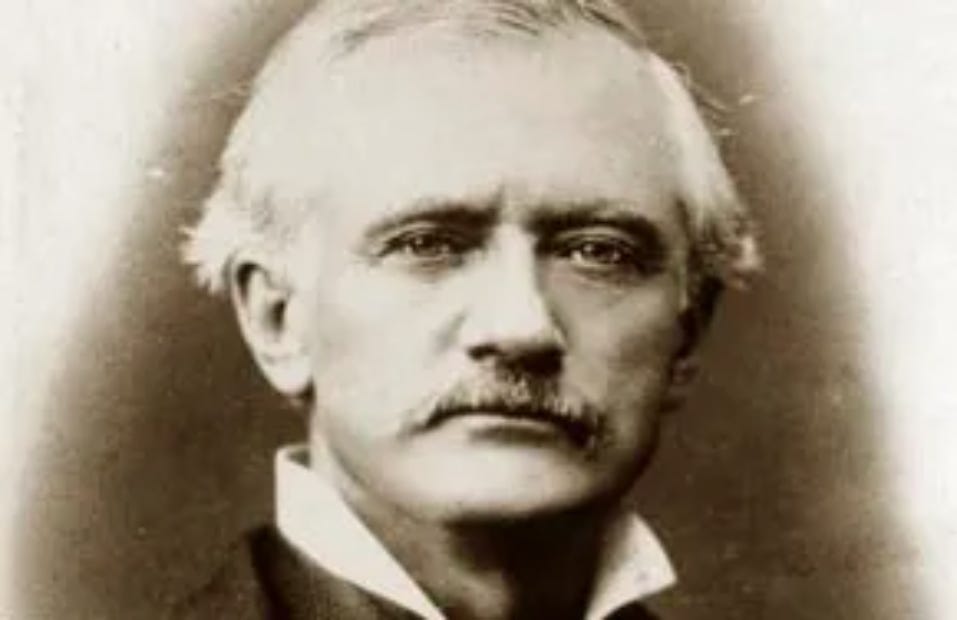

Local elites, led by businessman Alexander Shepherd, objected to biracial democracy in the city and convinced Congress to consolidate municipal power in the hands of political appointees rather than elected officials. In 1874, as Congress retreated from Reconstruction, it took the vote away from all Washingtonians, Black and white.

Senator John Morgan of Alabama, a former Confederate general, explained how racial concerns were at the center of the effort to disfranchise Washingtonians. The Black-supported local government was “abominable and disgraceful,” Morgan argued. Congress “found it necessary to disfranchise every man in the District of Columbia, no matter what his reputation or character might have been or his holdings in property, in order thereby to get rid of this load of negro suffrage that was flooded in upon them.” It was akin, Morgan said, “to burn[ing] down the barn to get rid of the rats… the rats being the negro population and the barn being the government of the District of Columbia.”

For the next century, the city was ruled by three presidentially appointed commissioners, all of whom were white men until the 1960s. During the civil rights movement, local activists noted that DC had become the nation’s first majority-Black city and pushed to “free DC from its colonial masters.” Their efforts led to the Home Rule Act.

Signed into law by President Richard Nixon in 1973, the act reestablished the city’s elected municipal government. Washingtonians could once again vote for a mayor and city council, as well as neighborhood commissioners, though Congress retained ultimate control over the DC government’s decisions.

The Home Rule Act was a major step toward full self-determination and generated political momentum for a DC Voting Rights Amendment that would treat DC “as though it were a state” to allow for voting representation in Congress. The amendment won support from staunch conservative senators such as Barry Goldwater of Arizona and Strom Thurmond of South Carolina (under pressure from his Black constituents). “Human rights begins at home, here in the nation’s capital,” Thurmond said as the Senate passed the DC Voting Rights Amendment in 1978.

But other Republicans, fearing that DC voters would elect Democrats, helped scuttle the amendment, and it was never ratified. In the past 40 years, Republicans have been almost unanimously opposed to any effort to empower DC.

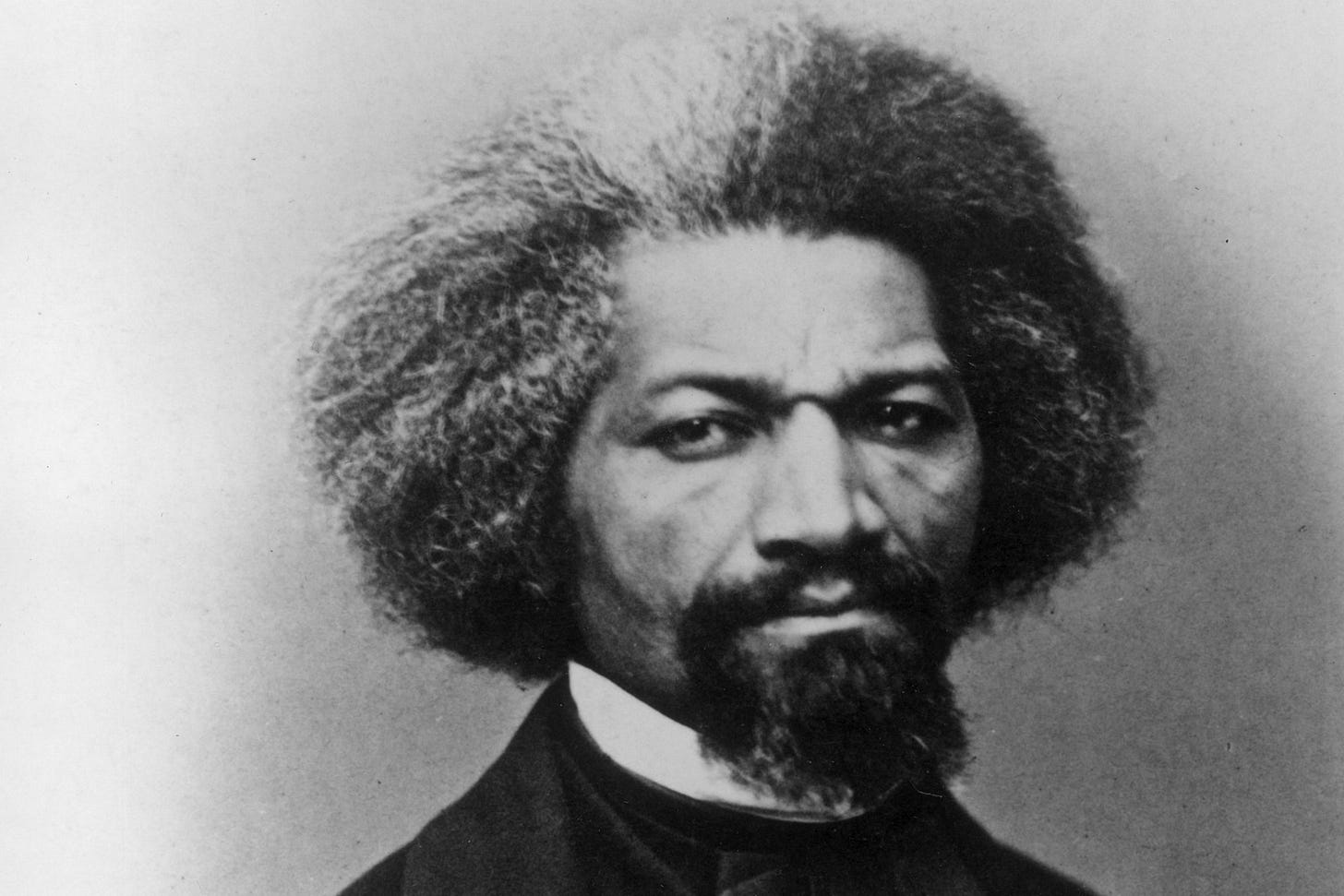

Since the demise of the DC Voting Rights Amendment, Washingtonians have pursued statehood as their chosen path to full citizenship. Statehood advocates call for shrinking the federal capital down to two square miles encompassing the National Mall, the White House, and the Capitol complex in downtown Washington. Everything else would become the 51st state, potentially called Douglass Commonwealth, after abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass.

There is historical precedent for shrinking the size of the nation’s capital. The Constitution says that the district cannot exceed ten square miles, but it does not specify a minimum size. In the 1840s, when District residents on the western bank of the Potomac clamored to be given back to the state of Virginia, Congress simply shrank the capital by about 20 square miles. It could do so again.

Some statehood opponents suggest giving the rest of the District back to Maryland, an idea called “retrocession.” But Washingtonians today vehemently oppose that idea, as do Maryland residents. DC has been separate from Maryland for 220 years. It has its own identity, culture, and interests. Forcing DC to become part of Maryland would be as unthinkable as forcing Maine to join back up with Massachusetts, as it was before 1820.

The House of Representatives passed a DC statehood bill in April 2021 by a party-line vote of 216–208, but the bill died in the Senate. A new bill, introduced in January 2025, remains stuck in committee.

Without statehood and representatives of their own, DC residents live with limited autonomy, knowing that Congress or the president could step in at any time to assert their supremacy.

Today, President Trump cites Section 740 of the Home Rule Act as justification for federal intervention on the city’s streets. For Washingtonians, Trump’s high-profile actions fit the long pattern of unwanted federal encroachment on local rights.

American citizens who live in our nation’s capital should no longer suffer from taxation without representation.

It’s always bothered me that DC had no representation but I didn’t realize the history behind it. Now I feel more than bothered. I also had no idea that more people lived there than some states. The more I learn about history, the more I realize that what’s happening now is nothing particularly new, unfortunately. When have we ever lived up to “liberty and justice for all”? We have a long way to go, yes we’ve come a ways, but man, we have a lot of work to do.

Thank you for the history and explanation of DC. It should be a state.