Who is Amy Coney Barrett?

Her faith and conservatism powered her way to the court

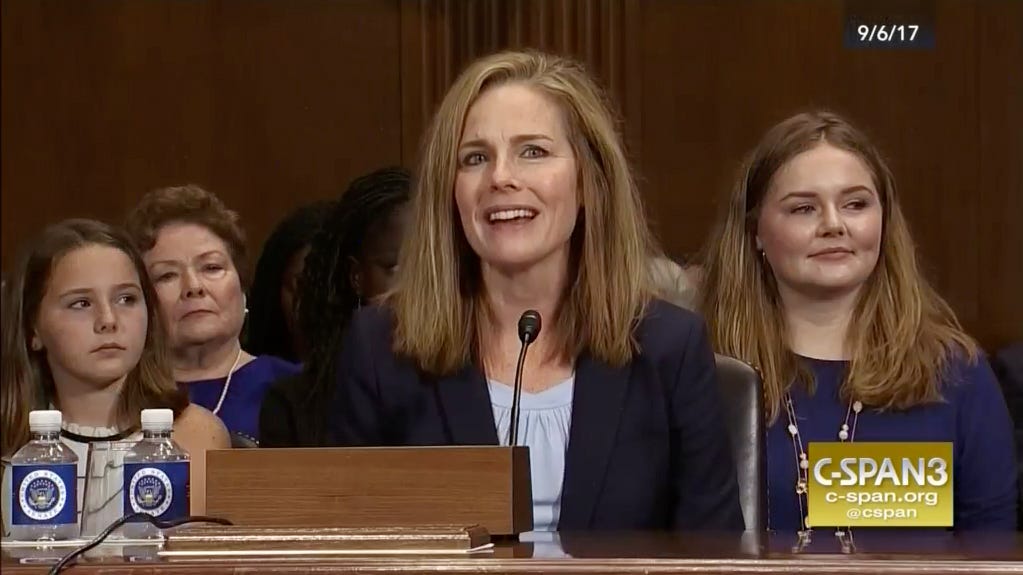

The hearing was tense. Democratic senators on the Senate Judiciary Committee had concerns about the nominee sitting in front of them, and they weren’t going to waste time in raising them.

The nominee, Amy Coney Barrett, had just been selected by then-President Donald Trump to serve on the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. Abortion rights groups raised concerns that Barrett, a law professor at Notre Dame and a devout Catholic, would not be able to separate her faith from the law, and it would impact her ruling on issues like gay marriage and abortion.

Senator Dianne Feinstein, ranking member of the committee, got right to the point, saying she was puzzled because Barrett had a “long history of believing that your religious beliefs should prevail.” She asked the nominee to discuss the Supreme Court precedents in Roe v. Wade.

Barrett explained that Roe “has been affirmed many times and survived many challenges in the court, and it's more than 40 years old, and it's clearly binding on all courts of appeals…and I would have no interest in…challenging that precedent.”

But Feinstein still wasn’t sure. She said, “Dogma and law are two different things. And I think whatever a religion is, it has its own dogma. The law is totally different.”

But something was giving senators on the committee an “uncomfortable feeling,” Feinstein said. She continued, “And I think in your case, professor, when you read your speeches, the conclusion one draws is that the dogma lives loudly within you, and that’s of concern when you come to big issues that large numbers of people have fought for years in this country.”

And it didn’t matter that Barrett said she would uphold Supreme Court precedent, because for almost a quarter of a century, Feinstein said, “every single person before us has said they’d be bound by [Supreme Court] precedent” which had upheld Roe. But, “they got there and voted the other way … over time, we learned to also judge what they think and whether their thoughts enable them to be free to observe the law.”

Barrett reiterated that if she had an opportunity to rule on Roe, “I would faithfully apply all Supreme Court precedent.”

This exchange made headlines, and “the dogma lives loudly within you” became a rallying cry of some of the conservatives who believed Barrett was being treated unfairly because of her faith. Barrett made it to the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, and just a few years later, she joined the Supreme Court bench.

Less than two years after that, she voted to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Welcome to our series on the nine Supreme Court Justices. This week is focused on Amy Coney Barrett.

Amy Coney was born in 1972, the oldest of seven children, to a mother who taught French and a father who worked as an attorney for Shell Oil. The family lived in Metairie, Louisiana, a suburb of New Orleans.

Her family’s devotion to their faith began with her father, who received word on his 17th birthday that his mother had died. He first felt angry at God in his grief, Michael Coney said, but then he remembered a passage in the Old Testament that goes, “The Lord gives and the Lord takes away.” Coney says this passage released his anger, and he considered becoming a Jesuit priest. But then, he met Linda Vath, and decided instead to marry her.

Around the time Amy was born, a priest was leading a new spiritual movement in the Catholic community in New Orleans. The priest was also the chaplain at Loyola University, where Michael was studying law, and Michael later described having a spiritual awakening during which he “sensed a call from the Lord to serve.” Afterwards, he felt another call to “live life in a close knit Christian community, one like described in the Acts of the Apostles, one that would help form our children into good Christians."

The Coney family became members of the People of Praise group (PoP) when Amy was young. Her father wrote, “the glue which binds the members of the PoP is a promise to share life together and look out for each other in all things material and spiritual.” The New York Times writes that the group is mostly made up of practicing Catholics, but they also draw on other Christian practices, like speaking in tongues (which Michael once wrote he began to do one night while praying).

From then on, the Coneys organized their life around the People of Praise. Other members of the community bought houses on the same block as the Coneys, and members of the group became deeply involved in each other’s lives. There were carpools and shared childcare.

Ailish Byrne, whose parents were members of the People of Praise in the 1970s and 80s said, “The community is more important than anything else in your life. It’s a whole different level than being a member of a church.”

Those who belong to the People of Praise are asked to donate at least 5% of their gross income to the community, and agree to “serve one another and the community as a whole in all needs: spiritual, material, financial.” The group believes in a traditional family structure, where women are “headed” by their husbands, because the group “communicates to all men their shared responsibility for the life of the community.”

The group was so important to the Coneys that when Michael, who was working for Shell Oil by that time, was asked to transfer to Houston in the 1980s, he decided to leave his family where they were in Louisiana and commute to Texas. For three months, he made the round trip regularly, but despite the raise and promotion the job in Houston offered him, he decided to quit.

He said, “Our life was in a covenant community in New Orleans. For the sake of our children and ourselves, we needed committed relationships with other Christians who were serious about their faith.” Shell later hired him back with the assurance he could stay in Louisiana.

As a child, Amy attended an elementary school associated with the church, and then attended the same school as all the women in her family, St. Mary’s Dominican, an all-girls Catholic school. Like most other Supreme Court justices, she was an excellent student, and a photo in the yearbook from her senior year shows her studying.

Once she graduated from high school, Barrett moved on to Rhodes College, a small liberal arts school in Memphis, Tennessee. As she worked towards her English degree with a French minor, it seemed like she would follow her mother’s footsteps and become a teacher. Barrett joined the school’s mock trial team, became a resident adviser, made friends, and went on dates. She belonged to the Catholic students association and the student honor council. Her sophomore year roommate called her, “straighter than most of us” but not “a stick in the mud at all.”

Amy considered being a nun, but as her roommate Shannon Papin said, “both she and her family felt that her talents pointed her in a different direction.” Inspired by her father, she decided to go to law school. Faculty members encouraged her to try and get admitted to Harvard, but she had her heart set on Notre Dame.

She later said, “I’m a Catholic, and I always grew up loving Notre Dame. I really wanted to choose a place where I felt like I was not going to be just educated as a lawyer. I wanted to be in a place where I felt like I would be developed and inspired as a whole person.”

So that’s where she headed in 1994.

Notre Dame claims it produces a “different kind of lawyer,” one who examines the “moral and ethical dimensions of the law.” The book Separate but Faithful, written by Joshua Wilson and Amanda Hollis-Brusky, says, “Notre Dame’s law school has done significant work not only to become one of the nation’s elite law schools, but also to become arguably the nation’s elite conservative law school.”

Amy moved in with friends of her parents, who provided her with home cooked meals and conversations that weren’t just about legal briefs. A classmate said that at Notre Dame, Amy was “obviously very Catholic and was always, like most of us, trying to figure out the intersection of your faith with this career.” She quickly rose to the top of her class.

It was at Notre Dame that she became an originalist, someone who strives to interpret the Constitution according to what it meant when it was written. She later said, “I wasn’t familiar when I entered law school with originalism as a theory. But I found myself as I read more and more cases, becoming more and more convinced that the opinions that I read that took the originalist approach were right.”

While in school, she partnered with Professor John Garvey on a law review article that said that because of their faith, Catholic judges might not be able to enforce the death penalty. They wrote, “while these judges are obliged by oath, professional commitment, and the demands of citizenship to enforce the death penalty, they are also obliged to adhere to their church’’s teaching on moral matters.” They said this puts Catholic judges in a “moral and legal bind.”

Notre Dame was also where she got her foot in the door with the Supreme Court. After she graduated in 1997, two of her professors, Patrick Schiltz and William Kelley, saw Barrett’s potential and helped her get a clerkship, first with Judge Laurence Silberman of the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Silberman hired her without an interview, and later told Kelley, “You undersold her.”

Silberman liked Barrett’s analytical skills and her clear writing. He made possibly the biggest introduction of Barrett’s career when he recommended her to Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. The men had worked together at the Justice Department a decade prior.

Garvey also sent a note to Scalia, writing, “Amy Coney is the best student I ever had.”

But still, she was “stunned” when she got the call offering her a clerkship at the Supreme Court under Justice Scalia. Scalia, who also proudly spoke of his Catholic faith, solidified her originalist beliefs.

Amy Coney went on to marry Jesse Barrett, another member of the People of the Praise. They now have seven children, two of whom are adopted from Haiti.

From Scalia’s chambers, Barrett moved on to a private law firm, Miller Cassidy, which was involved in George W. Bush’s legal fight following the contested 2000 election. Barrett helped with research and wrote briefs in the case, but she quickly moved back to Notre Dame, joining the faculty in 2002. The Barretts also liked that PoP was based in South Bend, IN, where Notre Dame is located.

As a law professor, Barrett joined Faculty for Life, an anti-abortion group, and signed a statement that criticized the Affordable Care Act for requiring private health insurance to cover contraceptives. Her family bought a house just a few blocks from campus, and she was voted teacher of the year. At 30 years old, she wore glasses to try to distinguish herself from her students.

In 2006, Barrett gave a speech to Notre Dame graduates, saying, “If you can keep in mind that your fundamental purpose in life is not to be a lawyer, but to know, love, and serve God, you truly will be a different kind of lawyer.” She told the graduates to pray before accepting a new job, give 10% of your salary away, choose a parish with an active community, and to build your social relationships within it.

Barrett joined the Federalist Society in 2014, a conservative legal organization that believes in originalist readings of the Constitution, and started to give more speeches, including at least five at the Blackstone Legal Fellowship, a summer program meant to inspire a “distinctly Christian worldview in every area of law.” During several of the years that she spoke, the program was sponsored by the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), a legal advocacy and training group that the Southern Poverty Law Center has defined as a “hate group” for its anti-LGBTQ+ views. (The ADL disagrees with their characterization.)

But it was her old mentor’s death that changed the trajectory of Barrett’s career. After Justice Scalia died, Senate Republicans refused to hold hearings for then-President Barack Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland, saying that it was an election year, and they should wait to see who won the presidency before moving forward with a new nominee.

Trump then took office, and nominated Neil Gorsuch to fill the seat. Trump’s team started discussing other judicial openings, and Donald McGhan, Trump’s White House counsel, decided to put Barrett on the list. She was nominated to the Court of Appeals in 2017, and her name was floated in 2018 when a seat on the Supreme Court opened. But Trump reportedly didn’t want to nominate Barrett yet, saying that he was saving a Barrett nomination for the seat that was occupied by Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Ginsburg died in September of 2020, two months before the presidential election, and Trump quickly put forward Barrett. During his nomination speech, Trump said Barrett was a woman of “towering intellect” and “unyielding loyalty to the Constitution” who would rule “based solely on the fair reading of the law.”

Democrats protested, not only because it was an election year and they had been denied their pick in 2016, but because they knew Barrett would likely vote to overturn Roe and the Affordable Care Act. Ultimately, they lacked the numbers to block her nomination, and Barrett took the oath of office one week before Election Day.

She recused herself from election cases that came before the court that October, saying they needed a “prompt resolution” and “because she has not had time to fully review the parties’ filings.” And in the end, she voted against overturning the Affordable Care Act. But since then, she has been a solid conservative vote, giving more rights to gun owners, voting against affirmative action, and granting Trump full immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts.

Despite her comments during her 2017 confirmation hearing on honoring precedent, Barrett was in the majority to overturn major precedents, including the abortion rights found in Roe.

She has become known for writing separate opinions in order to start a conversation or moderate the majority opinion. And though she’s voted most often with Justices John Roberts and Brett Kavanaugh, liberal justices see her as someone they can find middle ground with, and sometimes turn to her while drafting opinions.

As we look towards another Trump presidency, the court will likely be busy. And Barrett is only 52 – she has potentially 20+ more years to exert her growing influence on what the Supreme Court is, and what it will become.

Reading this one really triggered me. Maybe it’s because I went to the same high school as her (not same graduating year) and didn’t particularly enjoy my high school experience, or maybe it’s because her background eerily reads like something of a cult biography, or maybe it’s the hypocrisy of it all.

The first thing that occurred to me is:

Thou shalt not lie.

Barrett reiterated that if she had an opportunity to rule on Roe, “I would faithfully apply all Supreme Court precedent.”