What’s Happening in Syria, Explained

A brutal dictator is gone, but what now?

“We all feel like we've been under water, literally, for thirteen years, and we all just took a breath… And I know that there are so many people who are much older than me who have been through too much."

That was how one young Syrian described the news that rebels had overtaken the capital city of Damascus, bringing an end to Bashar al-Assad’s violent dictatorship.

She said not a single Syrian slept that night, awaiting word of Assad’s fate. After news spread of his ouster, there was singing and dancing in the streets, and celebratory gunfire.

But the question now is, what happens next in Syria, and what are the consequences for the broader Middle East?

Who is Assad?

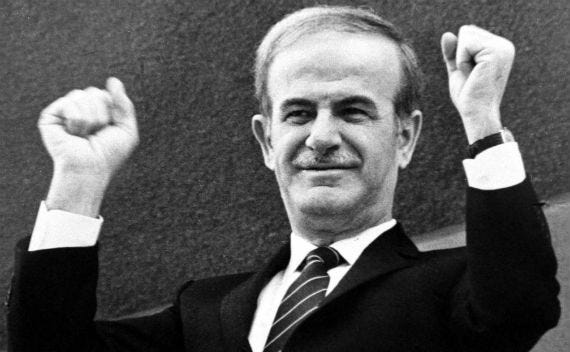

The now-toppled leader of Syria, Bashar al-Assad, has been in power since his father’s death in June 2000. At the time, the Syrian constitution said a person had to be 40 years old to be president, but that was quickly changed to 34, which was al-Assad’s age at the time.

He ran unopposed and quickly “won” the presidency the following month.

The al-Assad family has been in power in Syria since Bashar’s father, Hafez al-Assad, seized power in 1970, and became president in 1971. At least eight unsuccessful coups had been carried out in the country between the end of World War II and his successful power grab.

Hafez al-Assad ruled with an iron fist, in a manner modeled after the Soviets, knocking down dissent by using extreme violence against his own people, and holding onto the presidency with force.

Bashar al-Assad wasn’t the first born son, and therefore, wasn’t expected to succeed his father. Instead, he moved to London to study ophthalmology. But all that changed when his older brother, Bassel, died in a car crash in 1994. Bashar quickly switched course, learning about military science, and becoming a colonel in the Syrian army.

He and his wife, who is an investment banker of Syrian descent who grew up in London, have three children.

Why would people want to get rid of him?

When he took office, Bashar al-Assad suggested he would be a modern, progressive ruler, different from the kind of man his father was.

But he was nearly a carbon copy. For example: in 1982, his father bombed and bulldozed an uprising in the city of Hama, killing up to 20,000 of his own citizens.

In 2013, Bashar al-Assad used chemical weapons on Syrians in a Damascus suburb, killing hundreds, including women and children.

Assad deployed his secret police force to target anyone who dared speak against him or his government. Thousands of photographs smuggled out of the country showed how he and his police tortured political prisoners, including starving them, gouging out their eyes, and mutilating their genitals.

The country has been fighting a civil war since 2011, after protests sprung up against Assad’s brutal regime, and Assad cracked down on them as he always had: with ruthless violence.

Over the past 13 years, the country has been decimated, more than 500,000 people have died, and millions have fled. The instability caused by the civil war allowed terrorist groups like ISIS to thrive.

In 2015, when rebels came very close to overthrowing Bashar's government, he teamed up with militant groups backed by Iran and Russia to hold onto power. It proved extremely successful at the time.

But now, with the wars in Gaza and Ukraine, groups like Hezbollah didn’t have the resources or manpower to help him again, and rebels overran the country in just a few short weeks.

Who toppled him?

Over the years, several different rebel groups have tried to take down Assad. The New York Times calls them a “motley patchwork of rebel factions who were often at odds with each other.”

But this time, several rebel groups coalesced under the umbrella of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, a group that has previously been linked to the terrorist groups ISIS and Al Qaeda. Since it’s inception, it has used insurgent (including suicide) terror attacks in order to fight against Assad’s forces.

The group has recently tried to distance itself from its radical beginnings, and suggested it will be open to building a government led by civilians. But historically, this has not been true – in the past, they have supported an authoritarian and extremist form of government, not a democratic one.

The United States considers Hayat Tahrir al-Sham a terrorist group and has a $10 million reward for information leading to the arrest of the group’s leader.

That leader is Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, a 42 year old man born in Saudi Arabia to Syrian exile parents. In the late 1980s his family moved back to Syria, and he reportedly fought with Al Qaeda in Iraq against US troops in the early 2000s. He spent several years in a US prison in Iraq for his role in the fighting.

In a recent video interview from an undisclosed location, al-Jolani said, “Our goal is to liberate Syria from this oppressive regime” and he’s suggested he will be more moderate when it comes to governing.

But in one area that has been under the group’s control for years, women almost never go without wearing a hijab, although they aren’t officially required. The group has created a shadow government there, including collecting taxes and issuing identification cards.

Some residents in that province have protested the group’s rule, suggesting, like Assad, it has been imprisoning and torturing critics. They also complained the taxes were extremely high for residents who are suffering from “dire economic and living conditions,” according to a Syrian human rights group.

Where is Assad now?

Bashar al-Assad and his family got out of Syria just moments before rebels made it to his palace, which has since been looted and burned.

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a plane believed to have been carrying Assad and his family was able to leave just before rebels closed in on them early Sunday morning.

For a short time it was unclear where the al-Assad family was until Russian news agencies said they had arrived in Moscow and had been granted immediate asylum because of “humanitarian considerations.”

Putin and Assad have long been allies, and Russia has two military bases inside Syria.

Just this past summer, Assad and Putin met in Moscow, and while the extent of their discussions is unclear, Putin said they were there to discuss rising tensions in the Middle East.

According to Brookings, a non-partisan think tank, Putin has long supported Assad for a few reasons. First, Russia has profited from selling Syria weapons, and of course, they want to maintain their military bases there.

But analysts say it’s more about Putin’s own ego and fear of regime change himself. He’s long been worried of a potential plot to overthrow him, and similar to Assad, he’s also fought against rebel uprisings, like the one in Chechnya in the early 2000s. Also like Assad, Putin’s forces killed tens of thousands of his own citizens while crushing the Chechen rebels.

For now, Assad will have a safe place to stay in Moscow, but it’s unclear what his future holds.

He and his family are heavily sanctioned by the US and several other countries, meaning his access to money is severely limited. On Monday, the US extended new sanctions against Assad’s father-in-law, Fawaz al Akhras, who lives in the UK.

Why is the US bombing Syria now?

On Sunday, President Biden discussed Assad’s ouster, and his concern about terrorist groups taking advantage of the power vacuum left behind in Syria.

Because of that, the US began targeted airstrikes against ISIS camps and militants inside Syria, hitting 75 targets over the weekend.

General Michael Kurilla, who runs US Central Command, said “There should be no doubt — we will not allow ISIS to reconstitute and take advantage of the current situation in Syria.”

There are thousands of ISIS detainees currently being held by Syrian forces, and Senator Jeanne Shaheen, who is on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, says there are concerns about whether those militants could be released or escape.

At its strongest in 2014, ISIS terrorists controlled more than 30% of Syria and 40% of Iraq, before US airstrikes began pummeling the group. By 2017, ISIS had been nearly wiped out, losing 95% of its territory, but there’s always the concern that if they aren’t challenged, they could quickly regain strength.

What does this mean for the Middle East?

The security situation in the Middle East is being called a “Dumpster fire and a trainwreck all wrapped up in a Sharknado,” by Sen. Joni Ernst, a top Republican who is on a committee that monitors emerging threats.

President Biden said he was going to send US officials to the Middle East to discuss any potential security issues in countries surrounding Syria, including Israel, Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon.

Iran, which I mentioned before had long backed Assad, is a big loser when it comes to the fall of Syria, meaning its influence is now even more diminished in the region. Same with the militant group Hezbollah, which operates in Lebanon and has been fighting against Israel since last year.

Now, it’s anyone’s guess what a new government in Syria might look like and what its posture might be towards Israel and the West.

But it also means Syrians who had fled the fighting, are looking to go home. They are reportedly lining up at border crossings to get back into the country, and political prisoners are being freed.

Whether or not this new rebel group has good intentions for the Syrian people and the broader region remains to be seen. But for the first time in many decades, seeds of optimism have taken hold.

Several years ago, I taught middle school English learners and had a recently arrived student from Syria. Waiting for the buses one day, I noticed that his fingernail beds were very strange, sort of mangled. I asked him what had happened to his hands. His English was limited, but we had just finished a unit on the American government, so he was able to say: “I am baby, the government is angry at my mom. They want to make my mom sad. The government pulls off my fingernails and my mom sees. It’s ok, I can’t remember it.”

That description of torture will stay with me forever. I know the future is tenuous, but the Assad regime being gone is an important step for the Syrian people.

It is hard to grasp the horrors these people have been through. Some have been able to come to the US to escape the terrors and the violence they were living through yet Trump wants to deport them all…and people are cheering for that. It honestly breaks my heart to think about.