What Was Blown Up in the Caribbean Wasn't Just a Boat

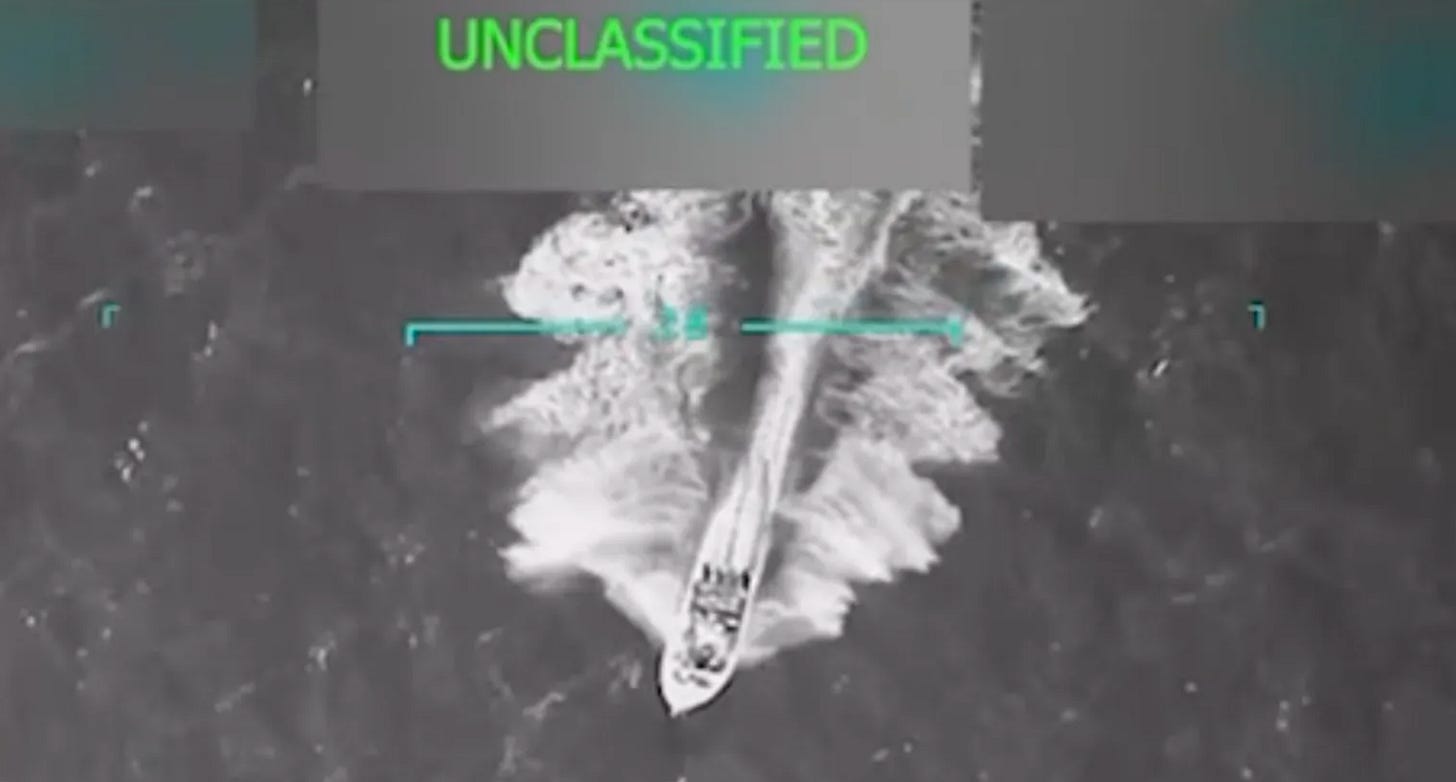

The explosion lit up the Caribbean night just off the Venezuelan coast. A 30-foot go-fast boat suspected of ferrying cocaine and fentanyl precursors toward American shores erupted into flames under US Navy fire. According to American officials, the vessel carried members of Tren de Aragua — a violent Venezuelan gang that has grown into a regional criminal syndicate with tentacles stretching from Caracas to Santiago to Miami. Eleven alleged traffickers were killed.

Little has been disclosed about the strike — including what legal authority it relied on and whether any drugs were actually aboard — but Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth insisted the intelligence was airtight. "We knew exactly who was in that boat. We know exactly what they were doing, and we knew exactly who they represented, and that was Tren de Aragua... trying to poison our country with illicit drugs," Hegseth told FOX News

Within hours, grainy infrared footage of the strike was cut into a slick video and posted on President Donald Trump’s Truth Social account: a boat in crosshairs, a blinding flash, and then black smoke curling into the sea breeze.

From the White House, Trump described the strike as a turning point, saying the boat was carrying "massive amounts of drugs coming into our country to kill a lot of people.” Secretary of State Marco Rubio said the president was going to “wage war” on drug cartels: “What will stop them is when you blow them up,” he said during a visit to Mexico City.

For supporters, the strike showed strength. For critics, it signaled something darker: America’s first officially sanctioned extrajudicial executions in the drug war.

From law enforcement to war

For decades, the United States treated drug trafficking as crime, not combat. Coast Guard cutters intercepted smuggling vessels, agents seized shipments, prosecutors built cases. Smugglers faced trial and prison, not summary death.

Trump is rewriting that playbook. In June, he designated several Latin American cartels and gangs — including Tren de Aragua — as foreign terrorist organizations, collapsing the distinction between criminal networks and enemy combatants. The move allowed him to claim that drug runners were terrorists, and therefore legitimate military targets.

What is Tren de Aragua?

Founded inside a Venezuelan prison in the early 2000s, Tren de Aragua has morphed into the country’s most powerful gang and one of Latin America’s fastest-growing transnational syndicates. What began as a network of inmates extorting fellow prisoners has expanded into a sprawling enterprise that dominates drug-smuggling routes, human trafficking, and illegal mining across Venezuela.

The group is notorious for its brutality. Investigators have documented torture, beheadings, and public executions meant to terrorize communities. Human rights groups say Tren de Aragua uses women and children as expendable labor in its trafficking networks. In border towns, it is accused of running migrant-smuggling rackets that funnel desperate Venezuelans through Colombia and into Central America.

Its reach now extends far beyond Venezuela. Cells have been detected in Peru, Chile, Ecuador, and Brazil, where they have clashed violently with local gangs. US law enforcement officials say the group has established a footprint in American cities with large Venezuelan migrant populations, particularly in Florida, Texas, and New York. A recent DHS intelligence bulletin warned that Tren de Aragua operatives are involved in fentanyl distribution and migrant exploitation schemes inside the United States.

By showcasing Tren de Aragua in its first strike, the Trump administration signaled both the scale of the threat it wants to highlight and the kind of enemy it is willing to kill without trial.

A legal black hole

But the strike rests on shaky legal ground. The “foreign terrorist organization” designation carries sanctions, not a license to kill. No statute authorizes the president to unleash military force on drug smugglers.

White House spokeswoman Anna Kelly said that the strike occurred in international waters and posed no danger to US forces. She added that Trump had ordered the attack to defend “vital US national interests” and in “collective self-defense” of other nations harmed by narcotics trafficking and cartel violence.

“The strike was fully consistent with the law of armed conflict,” she said.

International law allows lethal force at sea only in narrow circumstances: imminent threat, self-defense, or clear UN Security Council authorization. None applied here. Vice President JD Vance wrote on X that “killing cartel members who poison our fellow citizens is the highest and best use of our military.” But that claim is hard to defend given that Rubio conceded it was unlikely the drugs were headed for the US: “These particular drugs were probably headed to Trinidad or some other country in the Caribbean, at which point they just contribute to the instability these countries are facing,” he said.

Kenneth Roth, the former longtime head of Human Rights Watch, compared the strike to the actions of Philippines former President Rodrigo Duterte, whose “war on drugs” left thousands dead in extrajudicial street executions. The international criminal court charged Duterte for these executions, and he is now awaiting trial in The Hague.

The US military has rules too. The Uniform Code of Military Justice makes unlawful killing a crime. Past presidents relied on congressional authorization — the 2001 AUMF after 9/11, for example — to target terrorists abroad. The War Powers Resolution requires the president to notify Congress before using force abroad. Trump didn’t.

Senator Rand Paul (R-Ky.) expressed concern about the operation, telling Newsmax that Congress needs to declare war before the administration wages full-scale war on cartels.

A pattern of extrajudicial power?

Vincent Warren of the Center for Constitutional Rights warns, “These extrajudicial killings are a clear violation of international law. If there are no consequences, we should be extremely concerned about what comes next — will this administration begin executing alleged gang members or drug dealers at home without any judicial process?”

The strike isn’t an isolated incident. It fits a broader pattern of Trump pushing legal limits to pursue his agenda and admiring strong men who get their way, including Duterte.

Trump has spoken approvingly of how the Philippine leader ordered police and vigilantes to “just kill” drug dealers. Duterte claimed he would be “happy to slaughter” three million drug addicts.

During his first term, Trump reportedly told Duterte, “I just wanted to congratulate you because I am hearing of the unbelievable job on the drug problem. Many countries have the problem, we have a problem, but what a great job you are doing.”

With this strike, critics say, America is beginning to follow the Duterte model.

On Friday, seated in the Oval Office, the president remarked, “When I see boats coming in like loaded up the other day with all sorts of drugs, probably fentanyl mostly but all sorts of drugs, we’re gonna take them out. And if people want to have fun going on the high seas or the low seas, they’re gonna be in trouble… I think anybody that saw that is going to say I’ll take a pass.”

Echoes and precedents

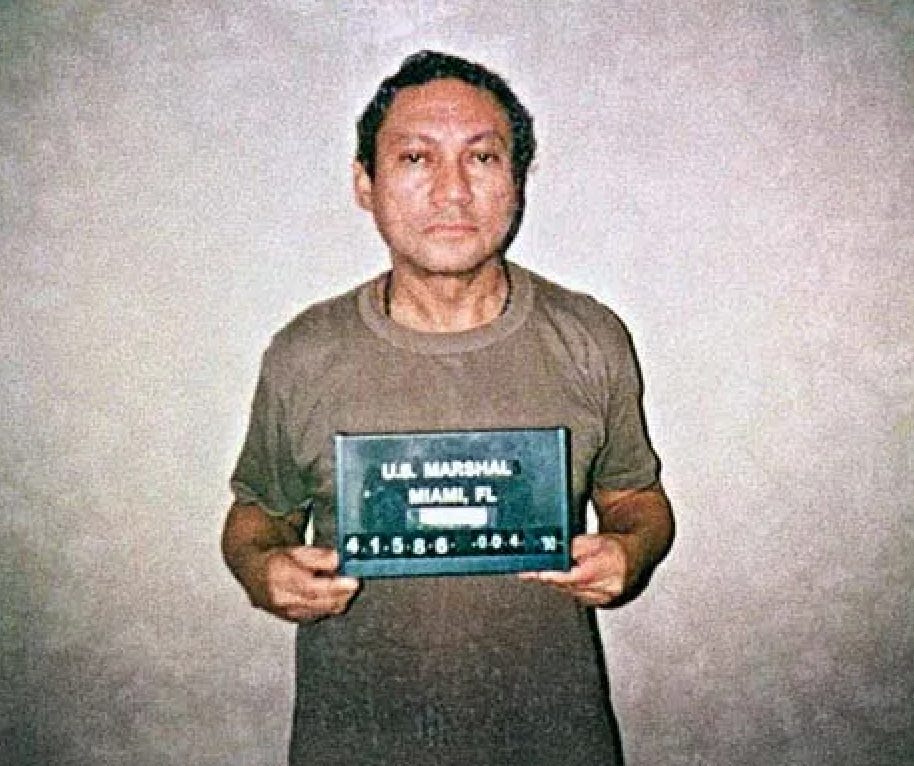

There is precedent for US force against traffickers. In 1989, President George H. W. Bush launched the Panama invasion that captured dictator Manuel Noriega, who had trafficked cocaine for years. But Noriega was arrested and tried in federal court, not summarily killed.

In the late 1990s, President Bill Clinton authorized the use of US planes to help South American allies interdict suspected drug flights. The program ended in disaster in 2001, when a Peruvian jet mistakenly shot down a small missionary aircraft, killing two Americans. The incident showed how quickly mistaken identity can turn lethal.

After 9/11, George W. Bush used the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force to justify global counterterrorism strikes. Barack Obama expanded those strikes through drone warfare, killing al-Qaeda and ISIS operatives far from battlefields. Critics warned of mission creep — but the targets were tied to groups that had attacked the United States. Trump has now taken the leap farther: applying wartime powers to drug smugglers.

Escalation in the Caribbean

The speedboat strike may be only the beginning. Trump quietly signed a directive authorizing the Pentagon to use force against Latin American cartels. Eight US Navy warships, a submarine, and Marine expeditionary forces now patrol the waters off Venezuela — the largest build-up in decades.

Officials openly hint at more action. “It won’t stop with just this strike,” Hegseth said. "Anyone else trafficking in those waters who we know is a designated narco-terrorist will face the same fate." Rubio predicted an era of sustained campaigns. On Friday Trump deployed ten F-35 fighter jets to the Caribbean to support operations against the cartels.

The geopolitical risks are high. Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro, already under US sanctions and facing a $50 million American bounty, warned of a bloody war in the Caribbean. A Venezuelan fighter jet recently buzzed a US destroyer in a dangerous show of defiance. Russia, Maduro’s chief ally, has signaled support for him.

Even US partners are uneasy. Colombia and Mexico, whose cooperation is crucial, have not endorsed Trump’s military approach.

What happened Tuesday would be considered “a murder anywhere in the world,” Colombia's president, Gustavo Petro, wrote on X. “We have been capturing civilians who transport drugs for decades without killing them.”

A question of efficacy

Behind the legal gymnastics and military maneuvers lies a sad reality: America is reeling from overdose deaths. In 2023 alone, more than 100,000 Americans died of drug overdoses, most linked to fentanyl trafficked through Mexico.

The strike was a deterrent message for drug smugglers that they will be viewed as terrorists once they enter international waters. But experts say cartels are decentralized and resilient. Killing eleven traffickers won’t change the supply chain.

Retired Admiral John Baumgartner, who commanded US Coast Guard operations in the Southeast US and Caribbean, said the move will likely deter allies, not traffickers.

“The United States has been a leader in building coalitions. We have done that on legitimacy. We have done that on the rule of law. This will deter all of those nations from cooperating with us and will do great harm to our ability to address this problem,” he predicted. “Will it deter an individual vessel from launching and trying to make a trek? I don't really know if it will.”

What’s at stake

The larger stakes are constitutional and global. Can a president unilaterally redefine crime as war? Can he bypass Congress, treaties, and courts to execute suspects at sea? And if drug runners can be recast as terrorists, who else might be?

What happens in the Caribbean may not stay there. Trump has already tested legal boundaries by claiming that gang members in the country illegally are foreign invaders who can be deported without due process under the Alien Enemies Act (a view that courts have rejected). The strike at sea signals that the war model can migrate anywhere.

The sight of a flaming boat may thrill Trump’s base. It may even rattle a few cartel operatives. But it also raises a stark question: Is America still a nation where the rule of law restrains the president — or is Trump establishing a precedent that the president alone decides who lives and who dies?

“Is America still a nation where the rule of law restrains the president — or is Trump establishing a precedent that the president alone decides who lives and who dies?”

I’m tired of this question! It’s been asked multiple times, by multiple people. We know the answer!

Yes, drugs are bad. Drug traffickers are criminals. That is a legal problem, to be dealt with by law enforcement.

But drug addiction is what is driving it. And drug addiction is a sickness. That is a public health issue.

Wage treatment, not war!

We’re inching closer to the infamous “5th Avenue” claim. Even more proof that when someone shows you who they are, you should believe them.