We Don’t Disagree, We Just Dislike Each Other

Getting to the bottom of what’s going on with polarization in America

Gift someone you love a year of fascinating stories, unparalleled insight, and a reason to hope. Purchase a gift subscription today, and you can schedule it to arrive at any time this holiday season.

We Don’t Disagree, We Just Dislike Each Other

To say that Americans are politically polarized feels so obvious that it almost seems silly to write an entire article about it (breaking news — the sky is blue!). But, despite massive attention to the topic of polarization across the media, speeches, and public opinion polls, it remains one of the more deeply misunderstood issues facing our country.

The term “polarization” connotes a country divided into two opposing ideological extremes, with the American people increasingly falling into either very liberal or very conservative camps. While there is strong evidence that American political leaders, including members of the House and Senate, are indeed ideologically polarized, there is little evidence that we are as ideologically polarized as is often assumed.

That’s the good news. The less good news is that we have less in common with one another than ever before, and we increasingly dislike and distrust the other side. That said, getting a better understanding of exactly how we are divided can help us address the real problem head on.

The hunt for red and blue America

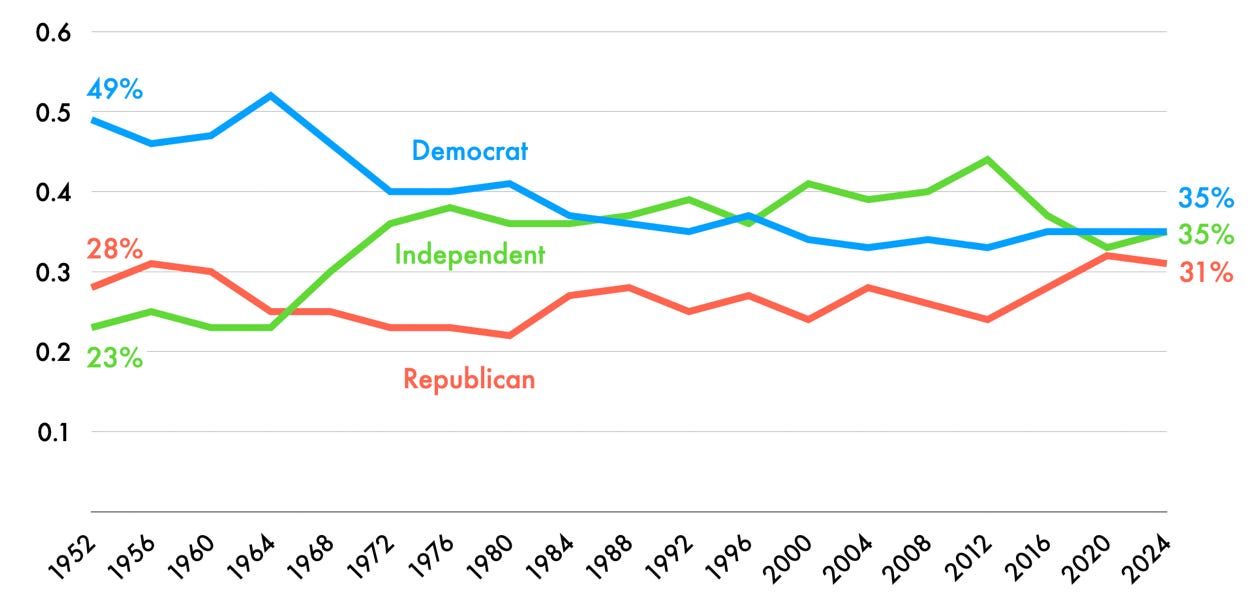

Political scientists have been searching for empirical evidence of ideological polarization among the American people for decades — and consistently come up short. For example, if we were more ideologically polarized today than in the past, far more Americans might identify strongly with a particular party today than they ever did previously. Yet for the most part our party identities haven’t shifted much since researchers started measuring it in the 1950s. If anything, we see a convergence towards independents today compared with last century.

Democrats, Republicans, and Independents each include about one-third of Americans

Percentage of survey respondents who indicated they identify as Democrat, Republican, or Independent, measured every four years since 1952

Source: American National Election Studies (ANES)

You might be thinking, okay, we don’t see wildly different numbers in terms of party identity over time, but maybe the strength of our party identities has increased. For example, we might not see meaningfully more Republicans today than decades ago, but perhaps people feel more strongly Republican than they used to.

That’s an enticing idea, but, alas, it also doesn’t have much support: according to the American National Election Studies (ANES) research project, one of the longest-running and most comprehensive national surveys of American public opinion, in 1952 about 40% of Democrats and 40% of Republicans each identified as “strong partisans.” In 2024, the most recent year of the survey, about 47% of Democrats and 45% of Republicans identified as such. There’s an increase, yes, but it doesn’t feel quite enough to warrant all the fuss about polarization.

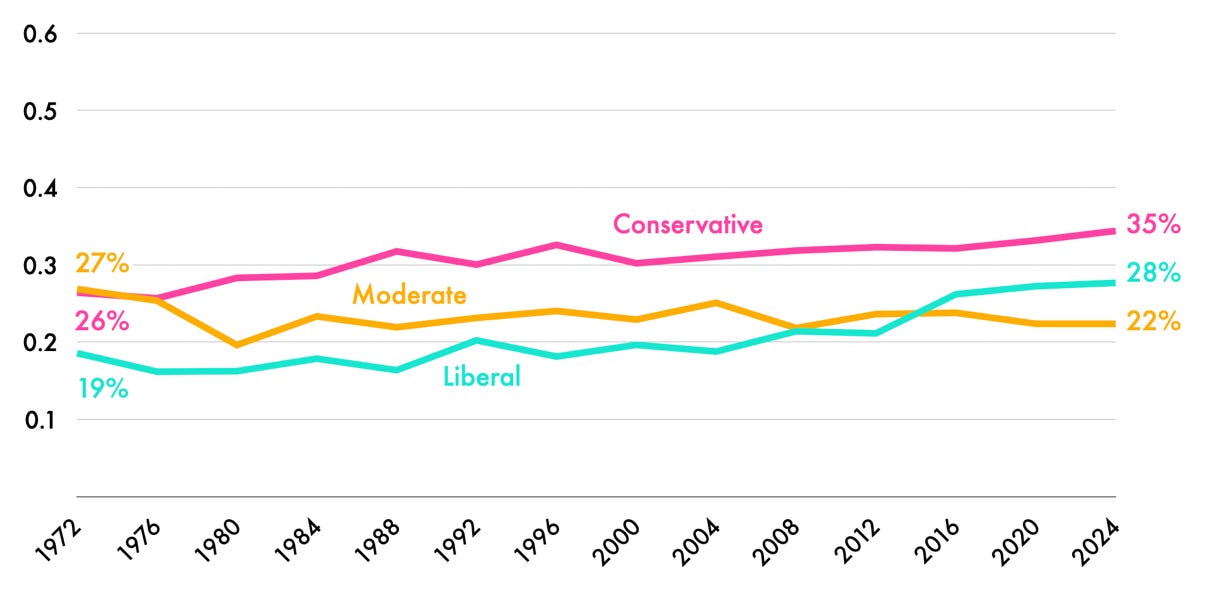

But perhaps we’re looking in the wrong place. It could be that the story of polarization in America is not about party identity or partisanship, but about ideology. Maybe our labels of “Democrat” and “Republican” haven’t changed, but our underlying pull towards conservative or liberal ideologies has. While we do see some evidence of a slight divergence in ideology since 1972 (the first year this was measured in the ANES), again it’s relatively modest compared with the misery that seems to characterize our politics.

Slightly more Americans identify as conservative or liberal today compared with decades past, but the shift is relatively small

Percentage of survey respondents who indicated they identify as conservative, liberal, or moderate, measured every four years since 1972

Source: American National Election Studies (ANES)

So, if we’re not more partisan and we’re not (meaningfully) more ideologically extreme compared with decades past, why does it all feel so awful? Things start to get interesting — and less fun — when we consider two things that have more meaningfully changed over the past decades: how sorted we are by party, and how we feel about each other.

Two ways we are actually divided

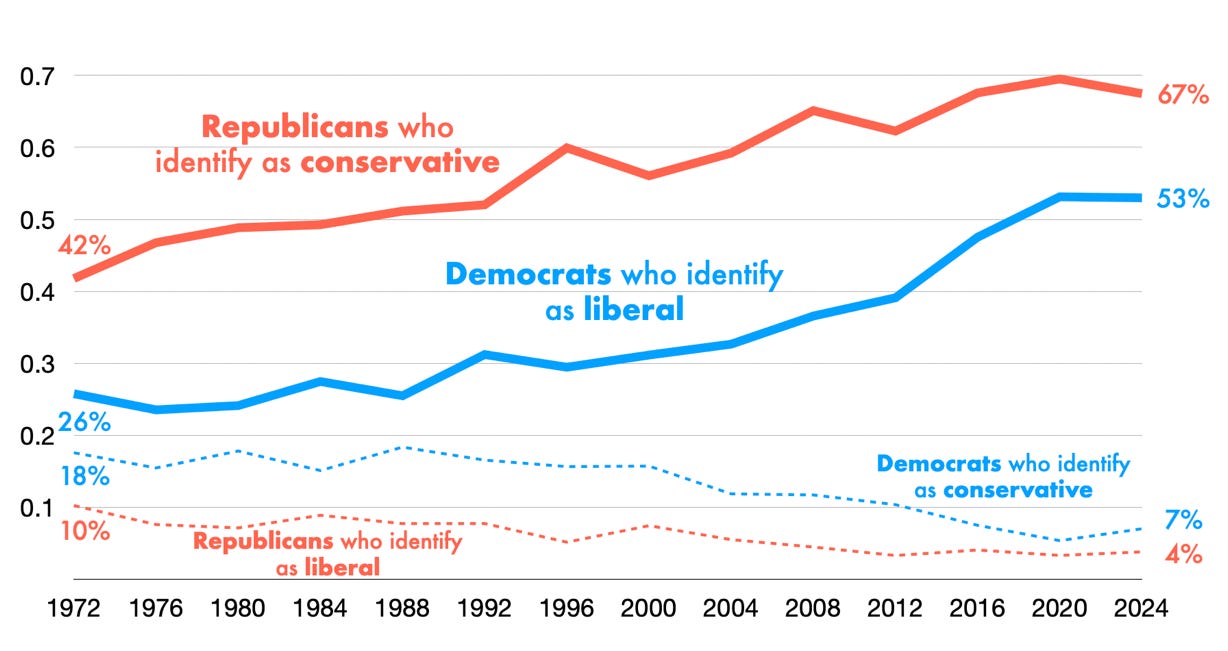

Party sorting is a powerful but subtle trend in which, though we are not necessarily farther apart in partisanship or ideology, our partisanship and ideology are more likely to track together. In other words, the common interpretation of ideological polarization is that Democrats who are liberal are becoming more liberal, and Republicans who are conservative are becoming more conservative. But this is not quite the story. Instead, what we’re seeing is some Democrats who were previously conservative have switched to liberal, with the converse happening on the Republican side. This means we aren’t necessarily seeing a rise in ideological extremism, just a more consistent alignment, or sorting, of ideology by party.

Another way to think about it is: if Americans were a bunch of magnets scattered across a table, we were once pointing every which way, regardless of party identity. But we are now sorted in such a way that our views line up according to party. It’s not that there are more people with conservative or liberal views today than there were in previous decades. It’s that people with conservative views are more likely to identify as Republicans, and people with liberal views are more likely to identify as Democrats.

It was not always the case that “Democrat” meant liberal and “Republican” meant conservative

Percentage of Republicans and Democrats who identify as conservative or liberal, every four years since 1972

Source: American National Election Studies (ANES)

One of the many implications of party sorting is that there are fewer points of agreement for Democrats and Republicans. While it previously might have been the case that a Democrat was liberal on abortion but conservative on guns and thus might have had something in common with a Republican who was also conservative on guns, there is increasingly little cross-party overlap on key issues.

We may not be farther apart ideologically, but we have far fewer issues on which we agree at all. Another manifestation of party sorting, in other words, is that knowing where someone stands on one issue currently tells you a lot about where they are likely to stand on other issues. Previously, this relationship was not so strong.

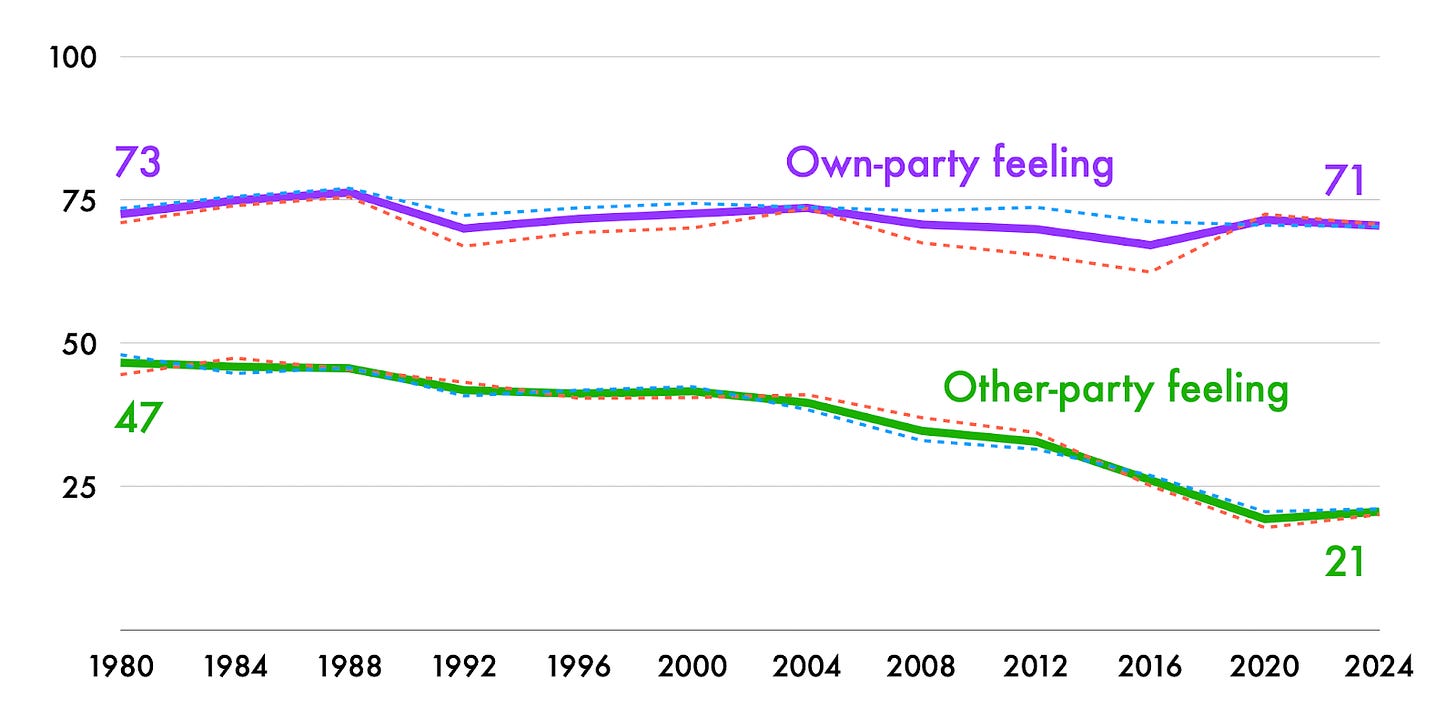

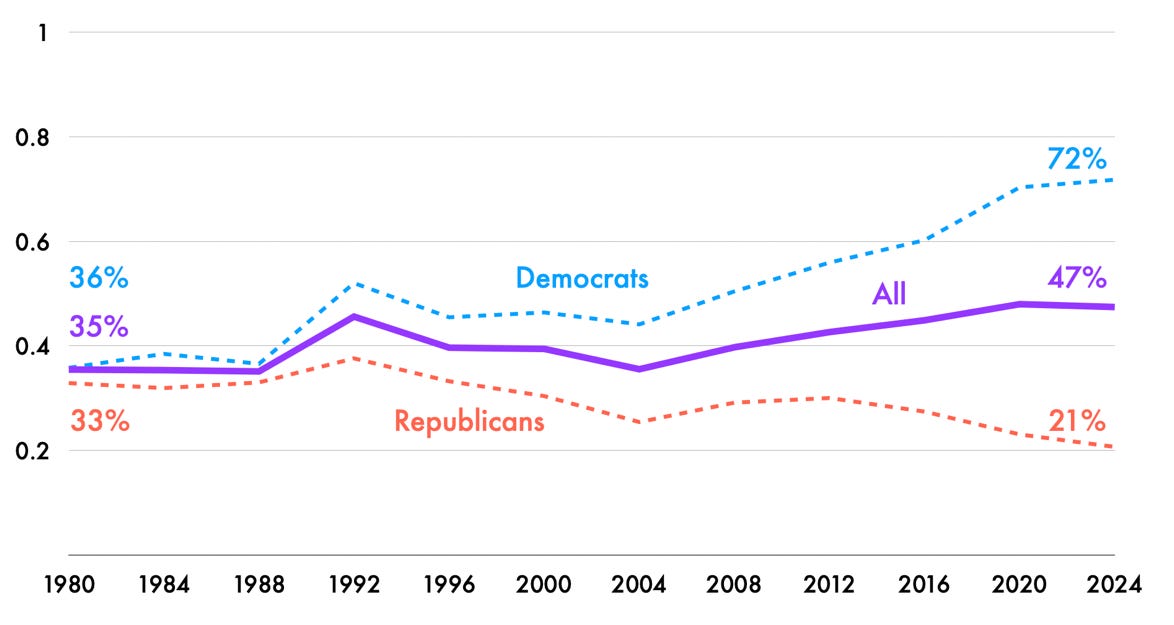

How we feel about each other has also shifted considerably in recent decades. The next chart shows the results of decades of asking Americans to rate their own party and the rival party in terms of a “feeling thermometer,” which in addition to being an extremely fun phrase is a standard metric that social scientists have developed to evaluate survey respondents’ attitudes towards other groups, people, or institutions. A temperature of 100 is “very warm” or favorable, and 0 is “very cold” or very unfavorable.

Feelings among partisans towards the rival party have plummeted

Average feeling thermometer rating for one’s own party and the other party, every four years since 1980

Source: American National Election Studies (ANES)

The solid lines represent all respondents. The light dotted lines break out the responses by party, which are included mostly to highlight how strikingly similar they are, apart from a slight dip in Republicans’ feelings towards their own party roughly during the Obama administration, which may reflect divisions within the party as they disagreed about how to react to his administration. The steady in-group feeling among Democrats during the same period is also consistent with Obama’s relatively high job approval among Democrats.

Political scientists have called this massive gap in favorability towards the other party “affective polarization,” which comes from the psychological term “affect,” referring to emotion. Surveys have found that both sides think of the other as hypocritical, closed-minded, selfish, and even evil, among other undesirable qualities. And this has real implications for how we live our lives, even beyond politics. For example, research finds we’re unlikely to be friends with, never mind marry, people from the rival party. And when we do talk to each other, we find it stressful and frustrating.

Oh, and cross-national surveys also indicate that Americans have experienced the largest increase in affective polarization compared with other developed democracies (USA! USA! USA!).

What can we do about all this?

While social scientists are still researching exactly what is behind these shifts, a few promising leads have emerged, which in turn raise a few possible pathways for improving things.

First, we deeply misunderstand each other. In one of the recent papers that perhaps most affected my own thinking about politics in America, in 2018 researchers found a “large and consequential bias” in perceptions of members of each party. For example, respondents in a national survey significantly overstated the percentage of Democrats who are members of the LGBTQ community, or a labor union, or a racial minority, as well as overstated the percentage of Republicans who are wealthy, evangelical, or over 65 years old.

Resources to Dive Deeper

Notably, both parties were biased about their own composition as well as the composition of the other, though the out-group bias was greater. So the first thing to do to address affective polarization is to recognize that our perceptions of the other party, and who its members are, may be wrong.

Second, party sorting may be contributing to our animus, both by giving us less to talk about with one another and thereby see the humanity in the other side, and also by increasing the alignment between our political identities and other identities. Not only are we more likely to see Democrats aligned ideologically, but we are more likely to see them aligned along race, gender, age, and other dimensions. Political scientist Liliana Mason argues that this is causing our political views to be increasingly part of our social and personal identities, so that political disagreements seem like personal attacks.

Third, we tend to hear more about divisive issues. For example, Americans are indeed ideologically divided on abortion, and the gap has been growing over time. Abortion is also a highly salient issue: in the leadup to the 2024 presidential election, one poll found that one in eight respondents named abortion as the top issue influencing their vote, and 52% of respondents indicated that even if it wasn’t their top issue, it was still very important.

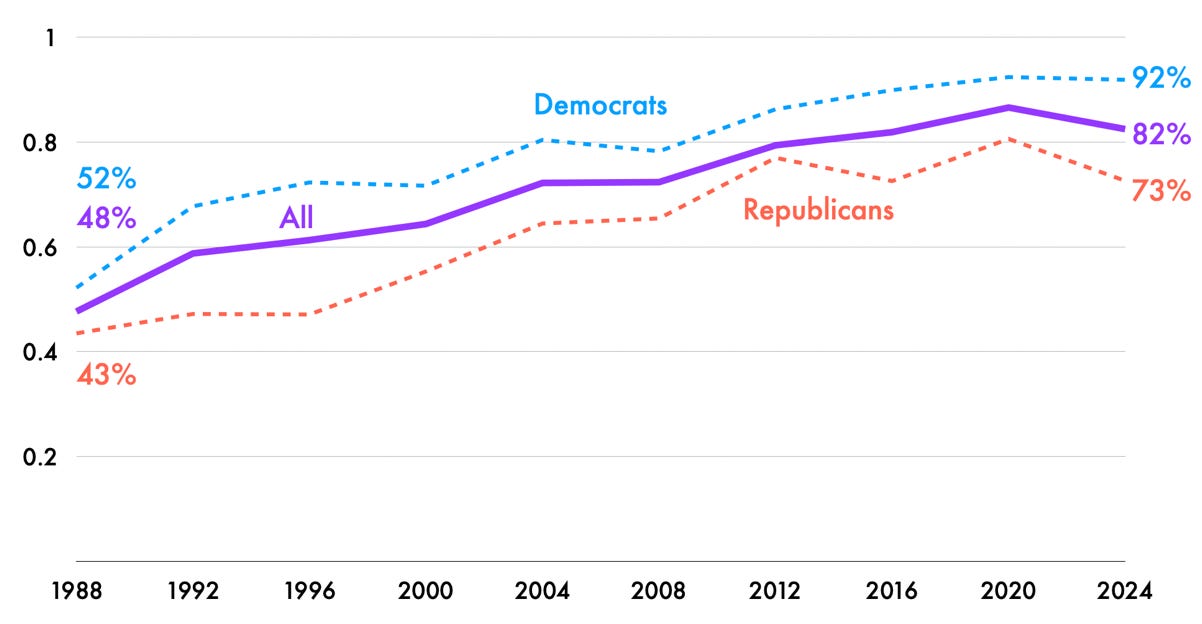

The gap between Democrats and Republicans on abortion is at an all-time high

Percentage of respondents who indicate that abortion should “always” be allowed by law, by party, every four years since 1980

Source: American National Election Studies (ANES)

On the other hand, we don’t hear much about legal protections in the workplace for the gay community, but there is also not a wide partisan gap on this issue. This is not to say it’s not a serious issue: a 2023 study found that 47% of LGBTQ workers have experienced workplace discrimination or harassment at some point in their lives, with 17% indicating they experienced it within the past year. Yet we don’t see questions about this topic in national public opinion polls or in most candidate stump speeches as we do with abortion.

Most Democrats and Republicans support workplace protections for the gay community

Percentage of respondents who indicated they “favor” laws to protect gays and lesbians from job discrimination, by party, every four years since 1988

Source: American National Election Studies (ANES)

In addition to abortion, there are wide partisan disagreements on climate change, transgender health care policies for minors, and government spending on public services. Americans have been found to agree, however, on medical marijuana, government child care support, and prescription drug prices, and to have similar attitudes about artificial intelligence, among other topics.

It’s also extremely important to note that even for topics on which there is something of a partisan divide, most Americans still tend to hold moderate or centrist views regardless of their party affiliation. For example, when it comes to gun control, Americans overwhelmingly agree that gun violence is a problem, that gun laws should be more strict than they are today, and that the minimum age for purchasing a gun should be increased. And even on the divisive topic of climate change, a healthy majority of Americans support our participation in international efforts to address the problem, as well as investment in alternative energy.

This brings us to another contributor to both affective polarization and our consistent misperceptions about how ideologically polarized we are: talk about polarization by leaders, in the news, and on social media.

Researchers have found that being told the other side is more ideologically extreme than it is may lead not only to misunderstandings of that side but also to adopting more extreme positions of one’s own. The good news is that the opposite is also true: pointing out that we have a lot of ideological overlap may lead to moderating one’s own views.

Other research suggests political leaders have incentives to generate strong emotional reactions by playing up our disagreements. This is consistent with one of the more surprising findings in this whole research area, which is that misperceptions of political polarization tend to be highest among those who are the most engaged in politics.

Finally, while it seems plausible that both legacy media and social media play a major role in the trends we’ve discussed, research results are in fact mixed. For example, polarization has been found to be highest among groups least likely to use the internet and social media. And most users in a 2022 study of Twitter didn’t even engage with political elites, although those who did were much more likely to demonstrate the kind of in-group and out-group biases documented above.

In addition, having partisan views may lead someone to consume more partisan news rather than the other way around. And while one often hears of “echo chambers,” the reality is more complicated. A recent study suggests social media algorithms are making things worse by exposing us to views starkly different from our own, forcing us to take sides and thus causing sorting.

Where does this leave us? I have a few recommendations. First, do everything you can to help share the news that we dislike each other more than we disagree with each other, including within our own in-groups. Second, talk to people you disagree with (easier said than done, but not impossible). Third, emphasize issues we agree on, not just the hot-button, divisive issues that are in the news. Fourth, challenge yourself to correct your own misperceptions of members of different parties in America. Finally, remember that extreme views are more likely to spread online, are more interesting ones, and are handy tools for politicians to energize their base. This is not to diminish the real harm extreme views can and do cause, but rather to serve as a reminder that just because we aren’t hearing about what we have in common doesn’t mean it isn’t there.

What Thanksgiving tradition still fills you with gratitude or brings your loved ones closer? Share it with us in a Letter to the Editor.

These are very interesting points I hadn’t considered before. I’m going to be more careful about my use of the word “polarization” because I agree it falls short of describing the truth.

From my perspective, my view of my own “side” hasn’t changed much beyond continually increasing disappointment in party leadership. What has changed dramatically is how I perceive the other side, and I think how the internet is governed, specifically Section 230, deserves a lot of blame.

Section 230 carved out tech platforms as not legally responsible for content users post on their sites, meaning that if Bob lies about me on TikTok, I can sue Bob but I cannot sue TikTok. The rule made sense back when we were talking about simple tech like a message board, or comments on news articles, but once these platforms became more powerful publishers than traditional broadcasters, it has started contributing to a public discourse with no guardrails. For instance, Fox News got sued by Dominion for spreading election misinformation relatively tame compared to what was catching fire on Facebook, but Facebook didn’t get sued, even though their algorithms actively promoted those lies to more passive users than Fox has viewers.

Until I started seeking out publications like The Preamble, Tangle, and various Substack independent journalists that present good faith descriptions of why people believe what they believe, my default internet diet was whatever got the most engagement: late night clips cherry-picking Republican voters to make them seem like monsters, or outrage bait about what the president said while ignoring things that actually affected my local life. Sure, a lot of people are monsters, but it’s not the full truth, and it’s not helpful to only focus on the worst ragebait. I would argue it not only poisoned our view of each other, but also has forced a lot of good people out of political discourse to protect their mental health.

These posts showed up in my feed not based on their value but because platforms like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter found the most inflammatory content and boosted it for profit. They kept me on the site posting reactions for hours. In the end, only the platforms and extremist politicians won. Regular folks, levelheaded candidates, and quality journalism lost. The graphs in the article back this up: the trend existed before the internet, but party sorting really accelerated after 2000, and feelings toward the other side tanked after the Facebook newsfeed launched. Correlation isn’t causation, but there’s a connection.

This problem is too pervasive and controlled by perverse incentives to let capitalist forces dictate how people see each other. We need serious constitutional reform clarifying that freedom of speech and press doesn’t mean tech companies (and the extremist narcissists who control them) get to bend our discourse to whatever they find most profitable. The default picture we get of the world should be closer to reality than this.

I’ve been working on a project to draft ten new constitutional amendments, getting feedback from people across the political spectrum, then demanding candidates in the 2026 midterms make these reforms central to their platforms. Think of it like a second Bill of Rights: pledges to fix gerrymandering, shorten election seasons, and reform how tech platforms warp our perception of each other. Even if we can’t pass all ten in a year, we can address the most pressing ones and keep momentum going.

The individual actions you outlined are great and important, but we also need the system to stop the bleeding. With a year left before the midterms, it’s time we turn this knowledge into action.

Thanks Andrea, for giving this topic the attention and science it deserves!

This is such an interesting article and I appreciate the way it breaks down polarization. The best part, the helpful suggestions at the end for what we as individuals can do. Thanks, Andrea!