We Already Tried the "Golden Age"

The truth behind the glamour

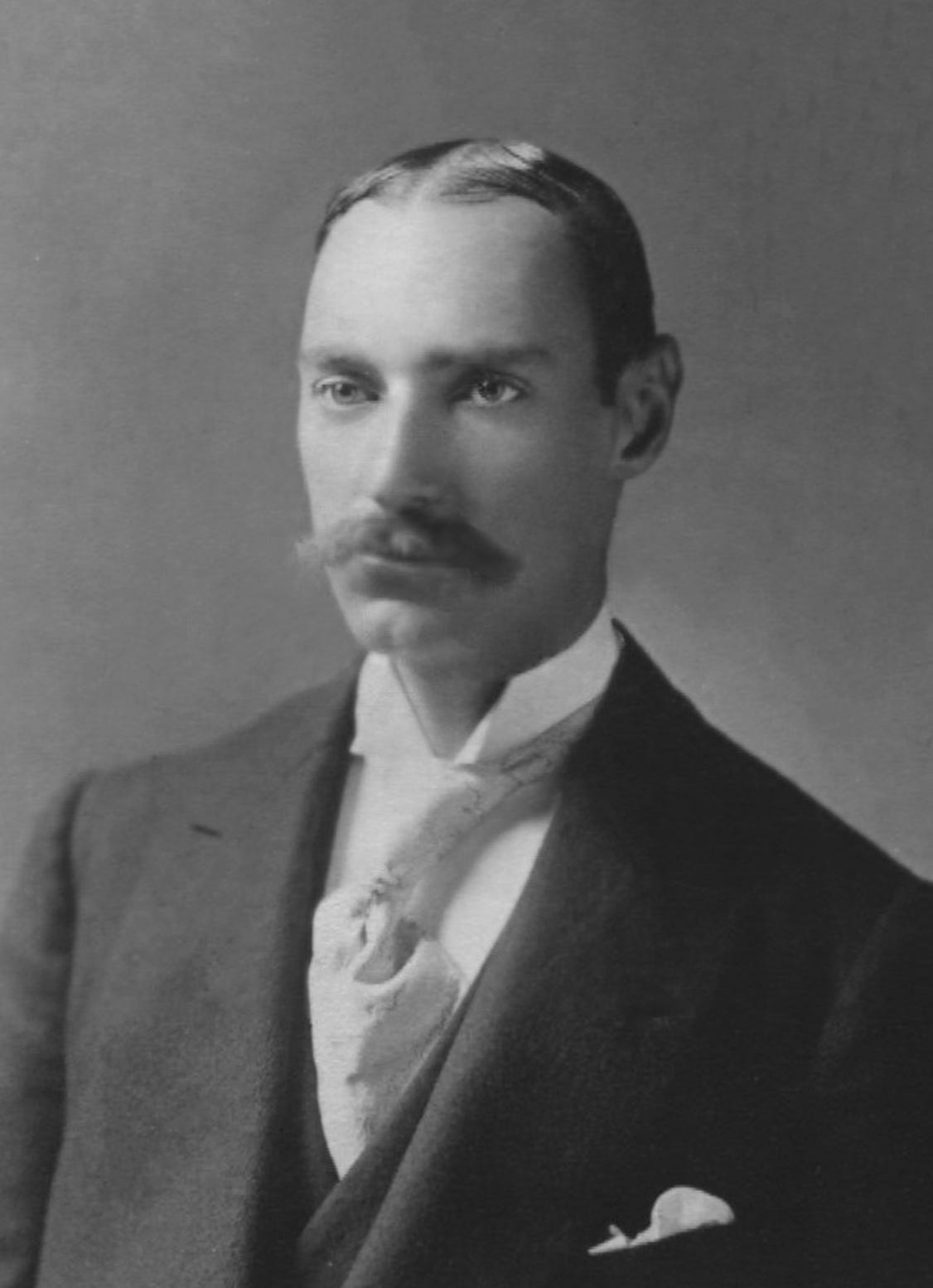

It’s probably a good thing Caroline Astor died in 1908. It spared her the anguish of knowing that just a few years later, her only son would perish as the supposedly unsinkable Titanic groaned to its watery grave.

Before her death, Caroline’s life was one of extraordinary privilege. She was born a Schermerhorn, one of the early Dutch families who came to New Amsterdam before control of the city was ceded to the British and its name changed.

“Lina” to her friends and family, but simply “Mrs. Astor” to New York society, Caroline’s approval could make or break a person’s status. A social snub by Mrs. Astor might haunt a New Yorker for years, while a recommendation could catapult them into the social stratosphere.

While Astor maintained a staff of 18 servants who wore green plush coats, white knee trousers, and black silk stockings, her marriage was an unhappy one. Her husband, wooed by the wiles of the sea, preferred to spend time on his yacht rather than home with his wife, and in the end, Mrs. Astor died alone in her mansion, her jewels little comfort as she passed the night before Halloween.

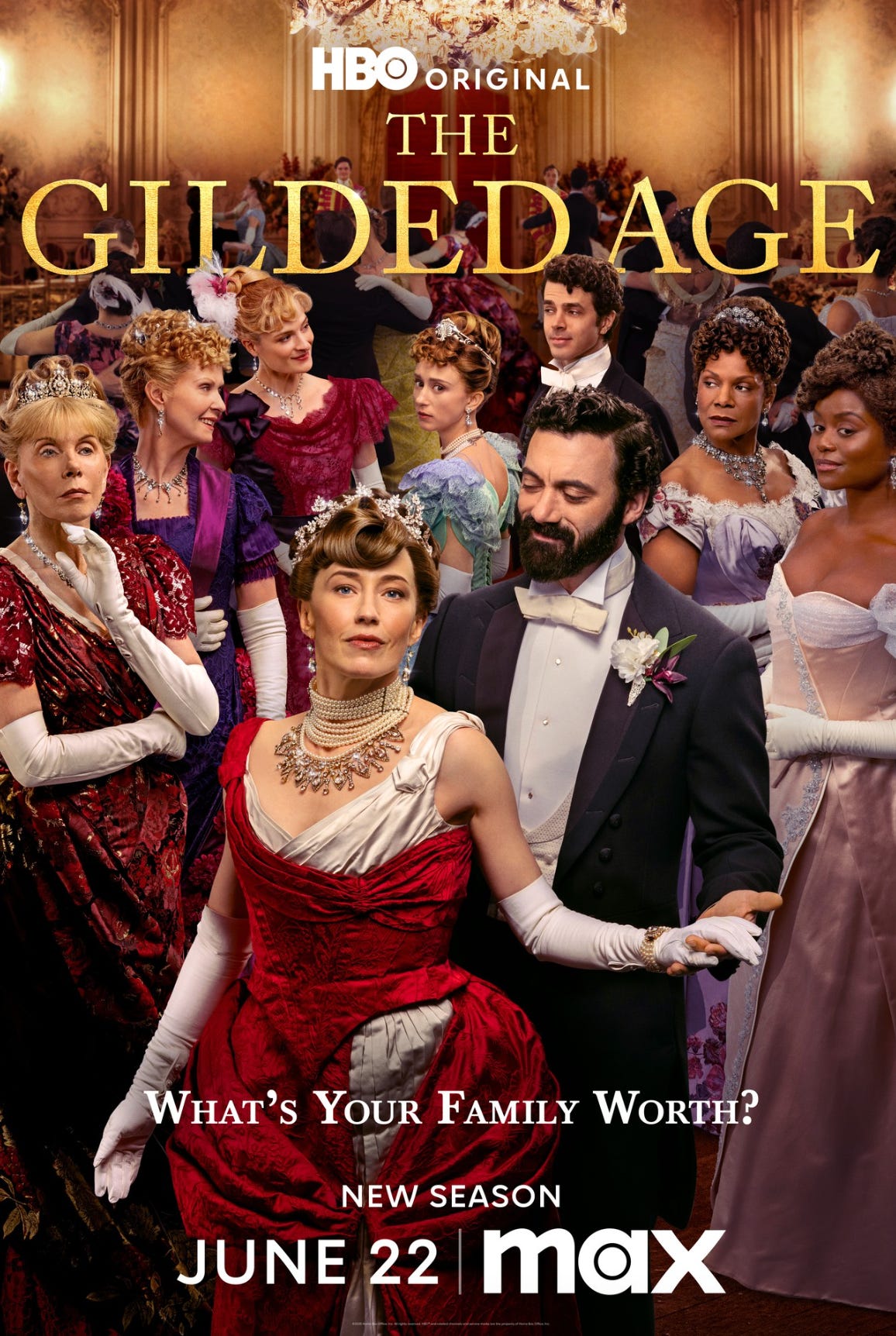

The Gilded Age is having a moment — both in the hit HBO show of the same name, and in the mind’s eye of the federal government, who has adjusted the name ever so slightly — calling it “The Golden Age,” but the implication being the same: life was fabulous then, and we should go back to it.

The show highlights the gorgeous fashion, the famous architecture, and the game-changing infrastructure projects of the age. Railroads, banking, steel, and oil all expanded beyond American’s wildest dreams. These new industries made some men so rich they could scarcely conceive of what to spend their fortunes on — was one Fifth Avenue mansion sufficient, or shall we also construct a second one in Newport?

By 1890, the richest 1% of Americans owned nearly half the country’s wealth, cementing a social caste system that Thomas Jefferson would have relished. You’d never find a working class person in a mansion on the Upper East Side of New York City, unless they were working there as a servant, butler, or cook.

But the TV show The Gilded Age — starring big names Christine Baranski, Cynthia Nixon, Nathan Lane, and Meryl Streep’s daughter Louisa Jacobson — romanticizes what it meant to be part of said working class. The show makes servitude seem surprisingly satisfying. The people who serve the fictional van Rhijn and Russell families have clean clothes and warm places to sleep in a large and lovely home. They eat pie and have time to work on personal projects, like building clocks. They have days off, and go for walks in Central Park.

And it’s this longing for a time when things seemed simple — Oh no, which rich people will help save the construction of the Met Opera House? — when it seemed political unrest didn’t infiltrate our daily consciousness, when economic worries apparently consisted of how to find a suitably rich mate from among America’s wealthiest families: it’s these problems that make us think we should long for, as President Trump and his surrogates say, “The new golden age of America.”

But all that glitters is not gold. The real Gilded Age was filled with communicable disease because of a lack of government regulation, extreme poverty and the skyrocketing of income inequality, and widespread corruption and cronyism.

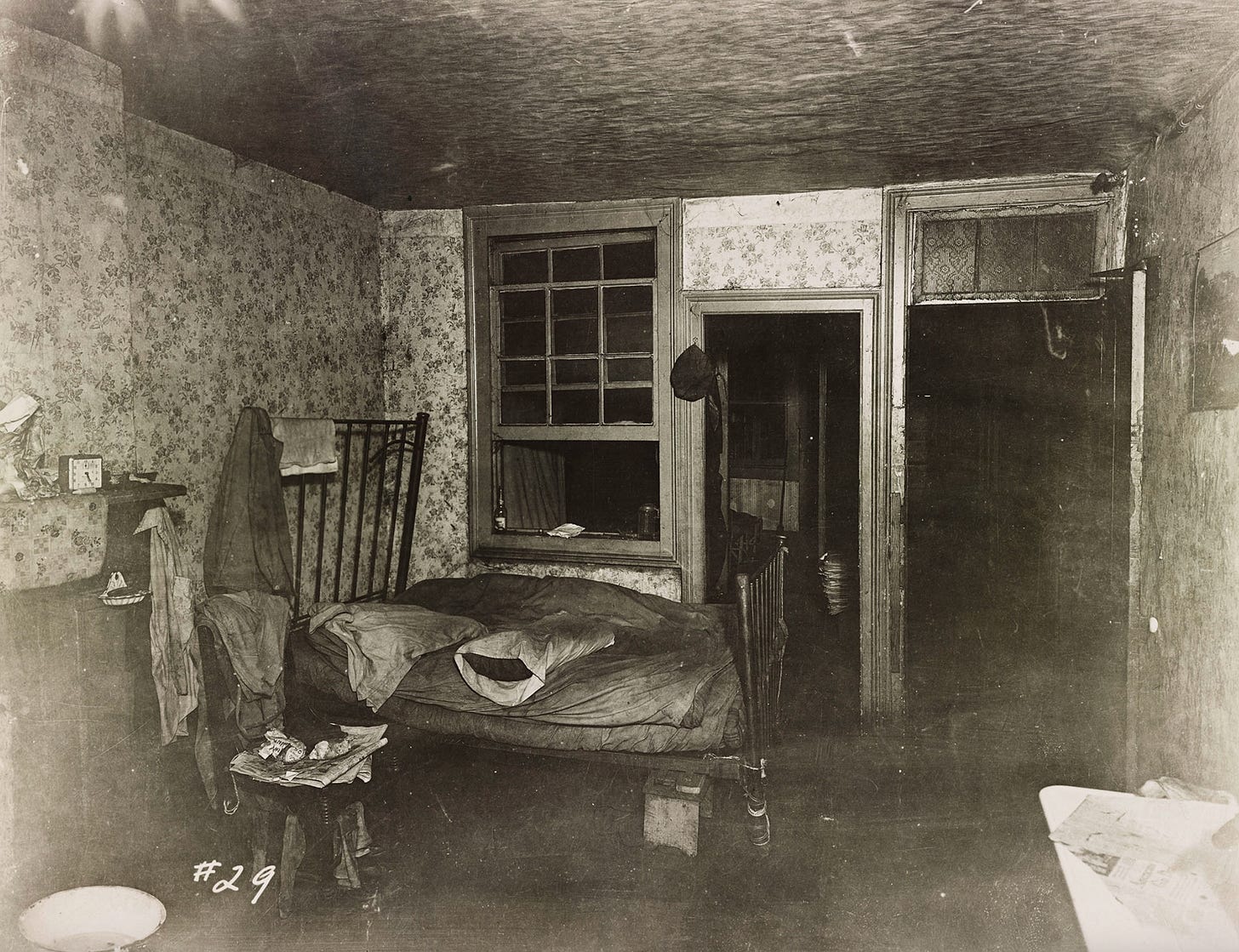

Much of the working class in the Gilded Age in New York lived in tenement housing. By 1900, about ⅔ of New York City’s population lived in small, poorly ventilated, cramped rooms, often with shared bathrooms. Diseases like tuberculosis, cholera, typhoid fever, and dysentery were common because of the unsanitary and crowded living conditions, and people in New York were often worse off during the Gilded Age than they were during America’s colonial period, meaning that despite 150 years of medical advancement, life expectancy and infant mortality changed for the worse.

Marble ballrooms didn’t keep the public healthy.

Workers — especially recent immigrants — labored in abysmal conditions, often 10-12 hours a day, seven days a week. In 1912, more than 18,000 workers died from work-related injuries. Laborers had few job protections and no ability to negotiate for better pay, so they took what they could. Unemployment was a constant fear.

When things couldn’t be controlled by firing workers, companies would employ scare tactics, like hiring detective agencies to infiltrate the ranks and dig up dirt to destroy anyone with leadership potential, sprinkling intimidation and threats of violence around liberally.

Media darlings titillating the press at lavish parties didn’t help the average person purchase a home.

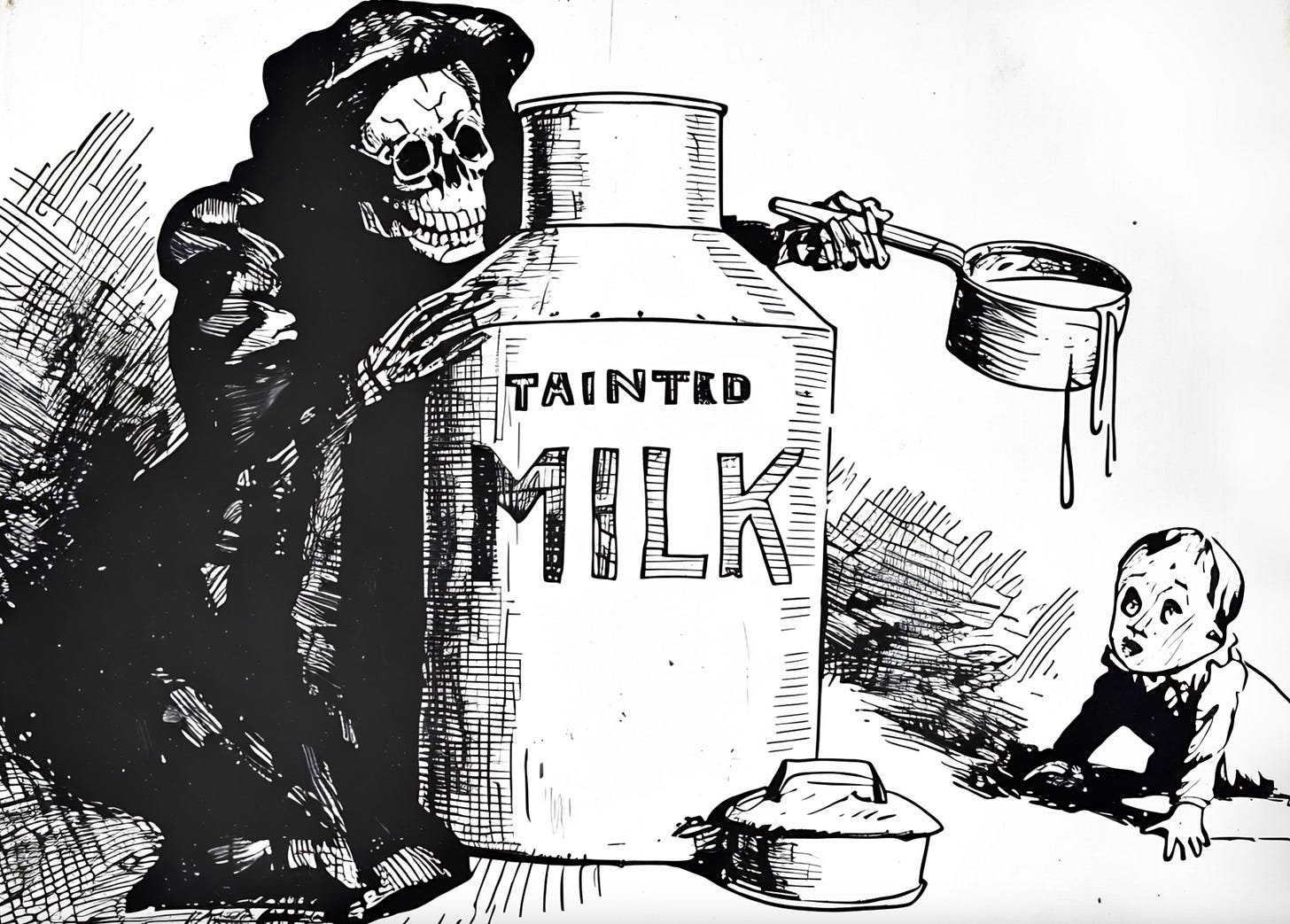

By today’s standards, a 4:00 pm tea time with china pots and miniature pastries seems like a delightful bookend to a stressful day. But the lack of regulation on food and drink actually meant that many people died unnecessarily. By way of one tiny example: In New York, cows for milking were kept in unsanitary conditions and fed “swill,” or leftover mash made from byproducts of whiskey distillation as a cost cutting measure.

Many Americans at the time thought cow milk was better than breastmilk, and mothers were urged to wean their babies quickly. But the whiskey mash was not nutritious for the cows, which began to produce milk that wasn’t a creamy white, but instead a sickening blue. So farmers added eggs, flour, and even chalk or plaster to make it appear whiter. The result was disastrous — thousands of children died from milk-related illnesses.

Hosting royalty at one’s summer home didn’t mean anything to those who couldn’t put food on the table.

The spoils system was still in full effect, with government jobs going to friends, donors, and relatives, and government funding conveniently siphoned into the same pockets. The influence of the country’s most wealthy on the government was apparent — robber baron Jay Gould bribed the brother-in-law of Vice President Ulysses S. Grant to help turn the president’s head to his way of thinking. (Gould sought to monopolize the gold market and wanted the government to stop selling its reserves of the metal.)

By 1886, the political power of businessmen and companies was such that former president Rutherford B. Hayes wrote in his diary, “This is a government of the people, by the people, and for the people no longer. It is a government by the corporations, of the corporations, and for the corporations.”

Despite our fascination with gowns of sumptuous silk and a handy lady’s maid or valet to arrange our hair each morning, a new Gilded/Golden Age would harm rather than help the lives of the ordinary.

The good news is that we are uniquely poised in this moment to turn from the ways of the robber barons and to reorient ourselves toward protections and reforms that benefit the common good, rather than the select view.

If the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice, it is we who must pull it. And the same is true of the political pendulum: our collective momentum can swing it faster from the folly of the age.

Where we go from here is up to us.

Isn’t it interesting how much it parallels the plantation life Jefferson so loved? The few becoming rich at the expense of slave labor, and everyone else fooled into thinking that was not only okay, but admirable.

Thank you, Sharon , for pointing out that everyone suffers when government does not protect us from greed. Why would we willingly choose to deregulate industries that profit from killing us?

Frightening how some want to go back in time. Thanks for this amazing reminder that all of the gold did not sparkle.