Trump's Plan: Raise Taxes on the Rich?

For decades, Republicans swore never to raise taxes. Trump might be the first to change that.

For decades, in Republican circles, it was known simply as The Pledge.

It made and broke candidacies. It was signed and cited and used as a cudgel. It shaped conservative policy for a generation.

It was also just a single (run-on) sentence:

That oath — known formally as the Taxpayer Protection Pledge — is circulated annually by the conservative group Americans for Tax Reform. Each year, hundreds of Republican lawmakers sign on; so have GOP presidential nominees like Bob Dole, Mitt Romney, and both Bushes.

But not Donald Trump. The president declined to sign the pledge during his 2016 campaign, although he didn’t raise taxes in his first term. Now, Trump is giving some conservatives heartburn, as he considers becoming the first Republican president in decades to endorse higher taxes on the wealthy. Will he actually pull the trigger? And how did an aversion to tax increases harden into Republican orthodoxy?

The story starts in the 1980s, when a pair of bills signed by Ronald Reagan slashed the income tax rate for the highest bracket from 70% to 28%, a historic decrease over less than a decade. Reagan wanted to keep his tax legacy secure, so he tasked Grover Norquist, then a 29-year-old speechwriter at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, with launching the nonprofit advocacy group Americans for Tax Reform.

During the 1986 midterms, as Reagan prepared to approve his final tax cut package, Norquist’s group began asking Republicans in Congress to sign commitments affirming that they wouldn’t double back on Reagan’s work and raise taxes in the future. Norquist’s pressure — and the fundraising dollars that went along with it — proved successful. In 2011, 60 Minutes said that Norquist “has been responsible more than anyone else for rewriting the dogma of the Republican Party.”

In his decades of advocacy, Norquist counts a single loss: in 1990, George H. W. Bush signed a bipartisan deal to bring the top tax rate up to 31%. Norquist often says that the measure — which violated Bush’s promise, “Read my lips: no new taxes” — is what cost Bush his reelection two years later.

No Republican member of Congress has voted for a tax rate increase since.

But the Republican Party is changing. In Reagan’s day, the GOP was propped up by a coalition he liked to call the “three-legged stool”: social conservatives, fiscal conservatives, and foreign interventionists.

Norquist has claimed that Trump is a fundamentally “Reaganite” figure, but Trump, at times, has spurned all three of those once-critical factions: pushing the GOP to moderate on abortion, accept ballooning deficits, and adopt a more isolationist posture.

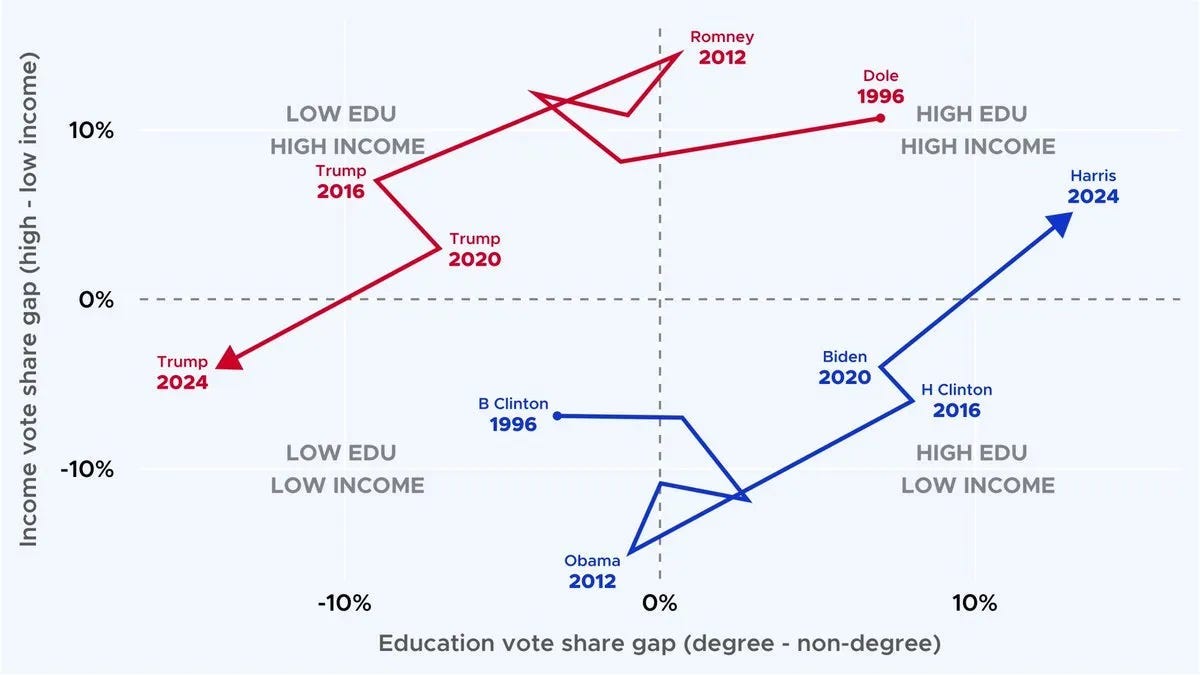

The party’s voters are changing, too. Consider this chart by Republican pollster Patrick Ruffini, showing that the two party coalitions have essentially swapped places since the 1990s.

You can watch as the share of the Republican coalition made up of highly educated, high income voters steadily falls, while the opposite transformation takes hold among the Democrats.

With that realignment in mind, some Republicans are asking whether it still makes political sense to avoid raising any taxes — even on the wealthy — as Norquist’s pledge demands.

The perfect opportunity for these Republicans is about to present itself: the tax cuts that Trump signed into law in 2017 are poised to expire at the end of this year, including a change that brought the top tax rate down from 39.6% to 37%.

According to the Washington Post, Vice President JD Vance is among those open to letting that tax cut for the country’s highest earners (the 0.5% who make more than $642,000 a year) lapse. From the outside, Republican strategist Steve Bannon — who fashions himself the keeper of Trump’s populist flame — has been pushing the GOP to take this option, or go further by creating an even higher tax bracket for those earning $1 million or more.

Trump himself — who said in 2015 that his tax policies would cost billionaires like him “a fortune” — has wavered on the question. He has reportedly expressed openness to raising taxes on the wealthy when talking to Republican senators, but in a recent interview with Time magazine, Trump seemed more hesitant.

“I actually love the concept, but I don’t want it to be used against me politically,” he said, citing the Bush example. “I would be honored to pay more,” Trump added, “but I don’t want to be in a position where we lose an election because I was generous.” (According to Pew, 58% of Americans, including 43% of Republicans, support raising taxes on Americans who make at least $400,000 a year.)

In a message to former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, Trump concluded: “If you can do without it, you’re probably better off trying to do so” — hardly a firm rejection of the proposal. A White House official told Semafor after the Time interview that Trump is still “weighing” the idea.

Most Republican leaders (true to the pledge they took to Norquist) remain opposed to the proposal, which makes it somewhat unlikely Trump would push it, and guarantees an uphill battle if he does (though GOP lawmakers have generally fallen in line when Trump has asked them to so far in his second term).

If Republicans don’t raise any taxes, though, a new math problem emerges: how to pay for extending the 2017 tax cuts? According to the Tax Foundation, the extension would cost $4.5 trillion over the next decade, and that figure doesn’t take into account other cuts Trump wants to add, including cutting taxes on tips and Social Security benefits, which would further reduce federal revenue.

Letting the top tax rate return to 39.6% would raise about $400 billion over 10 years, which would help the GOP offset the costs of extending the other tax cuts.

Otherwise, the Republicans will either have to massively expand the deficit or pay for the loss in government revenue by cutting spending for government programs like Medicaid, which provides health insurance for poor and disabled Americans. This would spark a competing set of political problems for a party still growing accustomed to its increasing reliance on low-income voters.

Bannon has publicly warned Republicans against cutting Medicaid spending (“A lot of MAGA’s on Medicaid,” he’s said), as have GOP lawmakers like Missouri senator Josh Hawley, who has expressed openness to raising taxes on the wealthy as well.

These fights are worth watching, not necessarily because 2025 is likely to be the year a Republican president signs a tax increase. What’s more interesting is what they tell us about the future of the GOP.

Ruffini, the pollster, has written about the split inside the GOP between “Vibes Populism” (offering populist messaging) and “Programmatic Populism” (pursuing populist policies).

Trump and many of his voters, Ruffini says, are more “Vibes Populists.” Back in November, he told me most Trump voters wouldn’t be fazed by tax cuts for the wealthy: “They just care about their own [taxes] being cut,” Ruffini said.

But another segment, the programmatic populists, disagree with that analysis, arguing that Republicans will maintain working-class support only if they write policy with working-class voters in mind.

(In addition to Medicaid, Republicans are also considering changes to the food stamps program, although Politico has reported that the White House is hesitant about those cuts as well, “with concerns mounting about benefit cuts hitting President Donald Trump’s own voters.”)

It’s notable that some of the GOP’s young firebrands, like Vance and Hawley, are on the populist end of these disputes, battling with graybeards like Norquist for supremacy over the next chapter of the party. Tariffs are yet another battle line; Vance and Hawley are supportive, while Norquist has long been opposed. (They are a form of taxation, after all.) With Vance poised to be the likely frontrunner for the party’s 2028 presidential nod, his stances — no matter what the GOP decides on taxes this year — offer a signal of where the party may be headed next.

Conversely, now that its coalition is growing significantly richer, it will be worth watching whether the Democratic Party makes the opposite move, adopting policies that are more friendly to high earners. This swap in demographics threatens to dismantle the status quo Norquist has spent decades building. “The idiot staffers at the White House don’t know any economics,” he recently fumed to the Atlantic, referring to advisers urging Trump to push for higher taxes.

Bannon, meanwhile, couldn’t be happier. “Politically, it’s game, set, match,” he told the Washington Post about a potential GOP-backed tax on millionaires. It’s a no-brainer. This would destroy the Democrats.”

This is just laughable to me. We already lose hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue every year because taxpayers, mostly high earners, don’t pay the taxes they owe, in large part because the Republican Party has tried to shrink and strangle the IRS for decades. People whine about deficits while simultaneously wrecking the government agency that brings in the vast majority of government revenue. Who cares if Republicans are even considering a return to slightly higher tax rates for the people at the top when Republicans are determined to cut the IRS workforce in half and take away Biden Admin. funds earmarked for modernization? This effort in itself is estimated to cost us trillions in lost revenue over the next decade, both from the high earners who already weren’t paying or even filing and all of the people who will now join them since there will be even less fear of enforcement from the IRS. This so-called “debate” among Republicans about tax rates on high earners is a bunch of sound and fury signifying nothing of practical effect. It’s just a pathetic fig leaf for their plans to gut Medicaid, SNAP and other programs so they can extend Trump’s tax cuts.

When Trump says economic pain is like "maybe the children will have two dolls instead of 30 dolls, you know?" what he should be saying is "maybe billionaires will have 12 mansions instead of 15, and still have more wealth than they could spend in ten lifetimes, you know?" But somehow he was elected twice.

It shouldn’t be about asking children to sacrifice their toys before asking people with obscene wealth to contribute meaningfully to the society that enabled their success in the first place.

I'm trying to wrap my head around this whole tax situation. Yes, Democrats' base has increasingly been wealthier and more educated compared to Republicans sliding in the opposite direction on both axes. But I think the partisan divide isn't so much about income per se - it's about trust in the government to responsibly use those funds in taxpayers' interest.

How about this for a Rorschach test: Some people fall for outlandish unproven accusations from Elon Musk and his DOGE about fraud and waste because the claims fit their bias, while others see DOGE as simply a conservative power grab because Musk can't and won't show receipts for his work. The deficit isn't just about spending, which is very difficult to change, but about revenue, which is just a matter of getting the ultra wealthy to pay their fair share. DOGE has gutted the government’s ability to seek revenue specifically from the wealthiest Americans. This has driven Progressive Democrats crazy, that working class people have seemingly shrugged about a tax revenue structure that benefits them. That's Bernie's entire thing.

As many people have said whenever the topic of DOGE comes up, but it’s worth repeating: fraud and waste exist. We all want to minimize it as much as possible. But not at the expense of honest people who rely on the government services they pay for.

I want to give working class Trump voters the benefit of the doubt, I really do. But it makes you wonder - if they sign up for peanuts from Trump while he gives out meaningful benefits to the ultra wealthy, meanwhile Bernie's singleminded focus on helping the working class didn't resonate..is it just because of social issues? Does that suggest that denying rights for people who are perceived as "other" has more political power than putting more money in your own bank account?

I just want people to be sane about this. The system is so broken. People who can't afford more should get a tax break. People who can afford more should get a tax increase.

Regardless of political background, we should all support: progressive taxation based on ability to pay; closing tax loopholes that only benefit the ultra-wealthy; protecting and strengthening social safety nets; ensuring corporations pay their fair share; and prioritizing economic policies that benefit the majority rather than just the top 1%. If we could all agree on these basic principles, maybe we could start rebuilding a functional government that works for everyone, not just those with enough money to buy influence.

Tangent: here's my personal story about income tax this year. Let's discuss the concept of tax brackets. I understand how progressive taxation works - only the additional dollars earned above each threshold get taxed at the higher rate, not your entire income. But even with this understanding, these arbitrary thresholds still create strange incentives and outcomes. What's wrong with a smooth graph that gradually increases the percentage without these stark dividing lines?

Historically, the U.S. adopted the bracketed system in 1913 with the 16th Amendment, starting with just seven brackets. Over time, the number of brackets has fluctuated dramatically - from a high of 56 brackets in 1918 to as few as two in the late 1980s. The original rationale was simplicity in calculation before computers, but many economists have advocated for a continuous tax function that would eliminate these arbitrary thresholds. Countries like Germany already use formulas rather than strict brackets to calculate income tax, which creates a smoother progression.

I have worked for the same project for 12 years, but that project has changed corporate ownership 3 times, meaning I have had 4 different employers (and 8 different work emails!), ranging from scrappy to now super corporate. Becoming more corporate had trade offs for the first 3 employers: added benefits but also restrictions on things like raises. But this last acquisition that came in August 2024 recategorized my role in a complicated way - I'm still technically a full-time employee, but I'm now excluded from all the benefits that people in other roles at the company enjoy, only because the technicality that my year-round full-time position is specific to a project. Nothing about my job requirement changed, but my benefits were converted to cash, meaning I got a pay raise that compensated me for the market value of the benefits I would no longer have.

Several meetings with HR later, when I made my case that this was effectively a pay cut because my additional income pushed me into a higher tax bracket and took away the tax advantages of the benefits I lost, I was told there was no negotiation, I could take the offer or resign. Being that everyone else I know in the entertainment industry has faced horrible options finding work for the past 2 years, my options were to go along with it or be unemployed for many months at least. Sure enough, even though this new arrangement was only for August through December out of the year, I was able to calculate that instead of what most people would expect would be standing still (a modest 3ish percent raise to keep up with cost of living) I was handed an 11% pay cut in terms of what actually stays in my bank account. That's because not only do I report more money as income than when that income came in the form of benefits, but that additional income gets taxed at a significantly higher rate than my base salary was.

Even despite this personal pain, I realize that I am fortunate and healthy enough that I should be contributing more, while folks with mouths to feed and debts that weren't their fault are hurting. I think we all need to look beyond our immediate self-interest to what builds a better society for everyone. Let’s not forget there are selfish reasons to want the best for everyone, too. But that would require a lot of change in the way we raise our children to think about government and taxes.