The Words That Ring True

Either we go up together, or we go down together

Today is Inauguration Day, and for a full rundown of the plans for that, see this newsletter.

Today is also Martin Luther King, Jr., Day. I was fully prepared to write an article talking about what Martin Luther King means to me. And I still may write that article someday. (Let me know in the comments if that interests you.) But something else rose to the surface.

Every year, I reread important MLK works. Not the highlight quotes, but I do my best to read something substantive, in context. Some years, it’s Letter From a Birmingham Jail, in which King talks about his disappointment, not with the racists who would rather see him dead, but with the white men and women who he didn’t think were doing enough. He wrote:

“I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers…I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: "I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action"...Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will.”

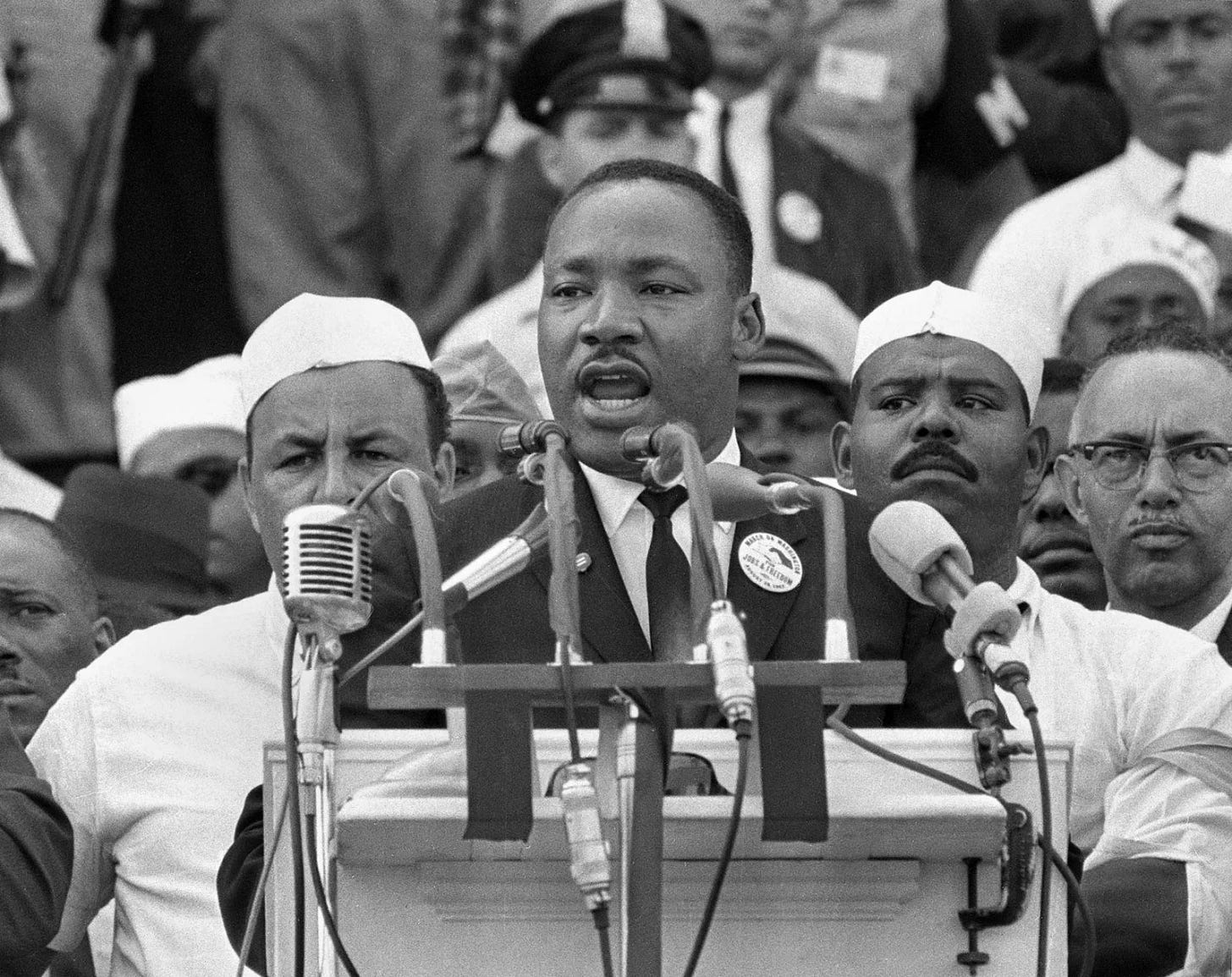

Some years I read the text of his I Have a Dream speech, where he says,

”Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quick sands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children.”

But this year, in 2025, I knew what I needed to read. It was King’s I’ve Been to the Mountaintop speech.

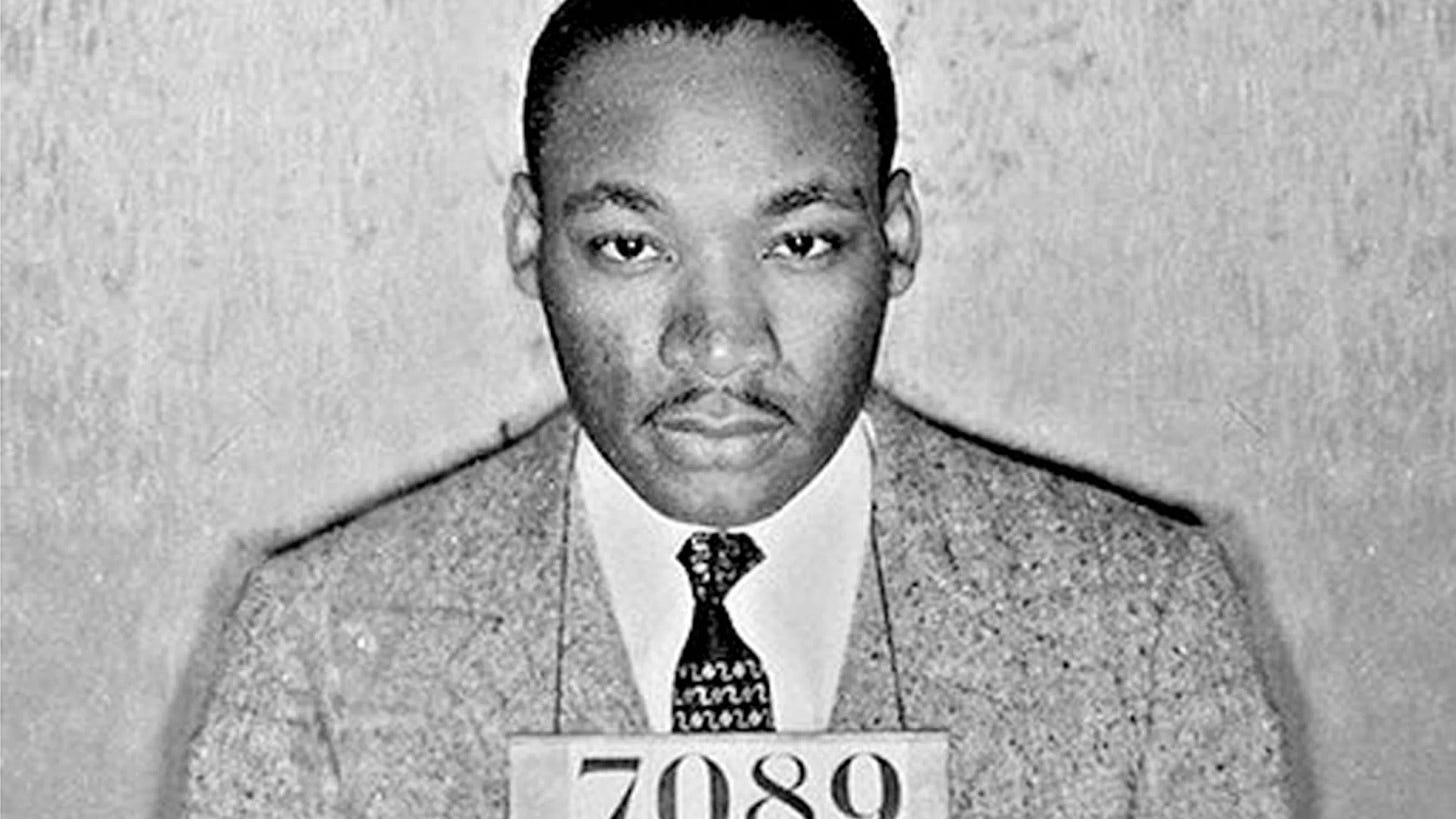

It was April 1968.

King went to Memphis to support a sanitation worker strike. The workers had been subjected to overt racial discrimination, resulting in bodily harm and death on the job. When King arrived, he was sick – he had a fever and a sore throat and was feeling so run down that he asked a friend to speak that night so he could get some rest.

The weather was terrible. And unbeknownst to King or the assembled crowd, storms were gathering in America, the likes of which they had not seen before. King’s stand-in, Ralph Abernathy, approached the podium and took the temperature of the crowd. He worried that he was a poor substitute for one of the greatest orators of all time, and hurriedly left the stage to call King on the phone, asking him, please, can you get down here? The people are here to see you.

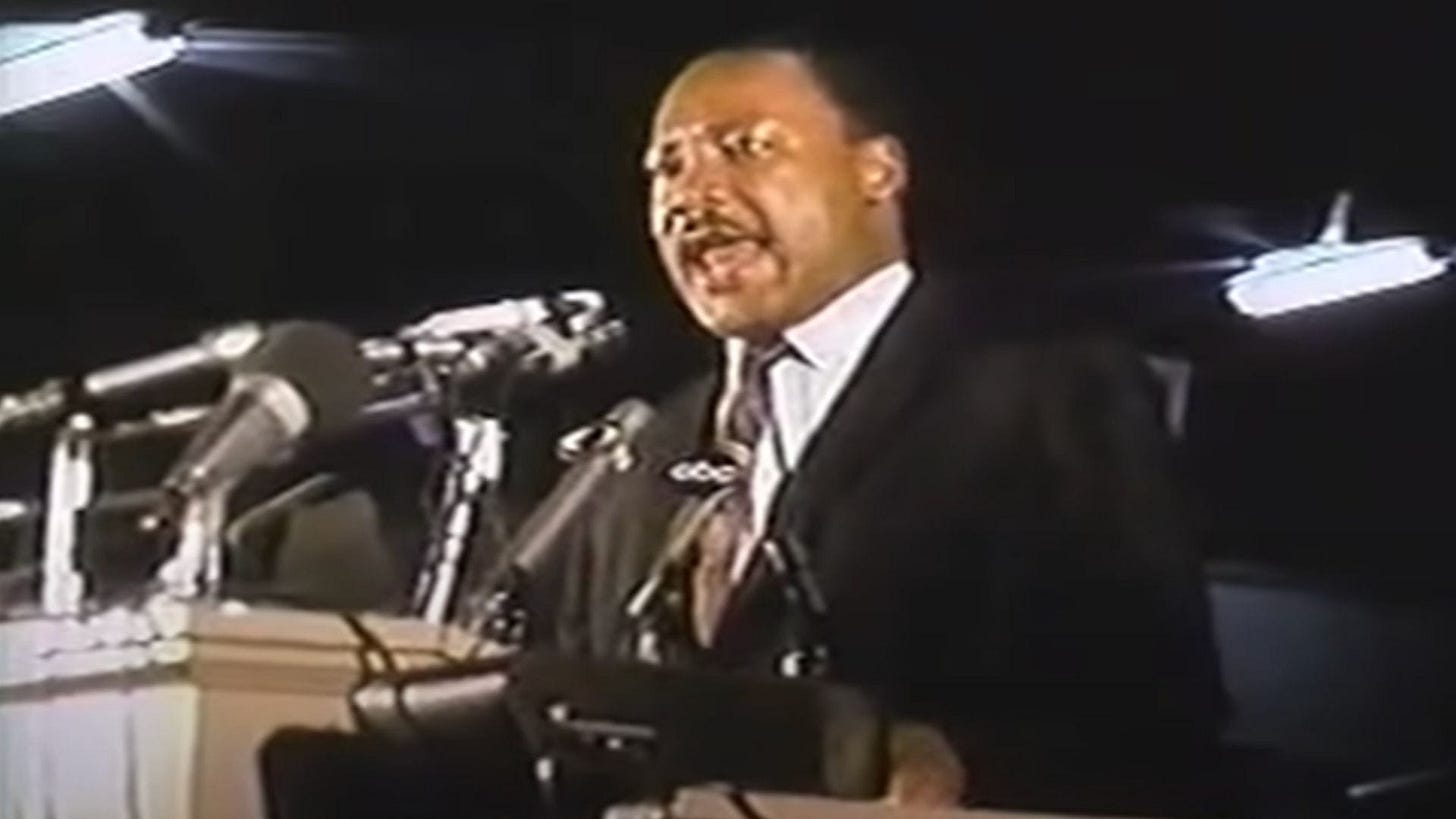

King fought his way out of bed and through the rain. He walked to the podium, ignoring the ache in his throat and the heat behind his eyes. He spoke off the cuff, as though he were channeling a force greater than himself. He spoke words that would reverberate through history so loudly that here we are, nearly 57 years later, still feeling the hair on the backs of our necks stand up when we hear them.

His speech has been called prophetic.

Because the next day, he would be dead, gunned down by an assassin outside a Memphis Motel.

King began by telling the audience a story:

“If I were standing at the beginning of time, with the possibility of a general and panoramic view of the whole human history up to now, and the Almighty said to me, "Martin Luther King, which age would you like to live in?" -- I would take my mental flight by Egypt through, or rather across the Red Sea, through the wilderness on toward the promised land. And in spite of its magnificence, I wouldn't stop there. I would move on by Greece, and take my mind to Mount Olympus. And I would see Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Euripides and Aristophanes assembled around the Parthenon as they discussed the great and eternal issues of reality.

But I wouldn't stop there. I would go on, even to the great heyday of the Roman Empire. And I would see developments around there, through various emperors and leaders. But I wouldn't stop there. I would even come up to the day of the Renaissance, and get a quick picture of all that the Renaissance did for the cultural and esthetic life of man. But I wouldn't stop there. I would even go by the way that the man for whom I'm named had his habitat. And I would watch Martin Luther as he tacked his ninety-five theses on the door at the church in Wittenberg.

But I wouldn't stop there. I would come on up even to 1863, and watch a vacillating president by the name of Abraham Lincoln finally come to the conclusion that he had to sign the Emancipation Proclamation. But I wouldn't stop there. I would even come up the early thirties, and see a man grappling with the problems of the bankruptcy of his nation. And come with an eloquent cry that we have nothing to fear but fear itself.

But I wouldn't stop there. Strangely enough, I would turn to the Almighty, and say, "If you allow me to live just a few years in the second half of the twentieth century, I will be happy." Now that's a strange statement to make, because the world is all messed up. The nation is sick. Trouble is in the land. Confusion all around. That's a strange statement. But I know, somehow, that only when it is dark enough, can you see the stars. And I see God working in this period of the twentieth century in a way that men, in some strange way, are responding--something is happening in our world. The masses of people are rising up.

Now, what does all of this mean in this great period of history? It means that we've got to stay together. We've got to stay together and maintain unity. You know, whenever Pharaoh wanted to prolong the period of slavery in Egypt, he had a favorite, favorite formula for doing it. What was that? He kept the slaves fighting among themselves. But whenever the slaves get together, something happens in Pharaoh's court, and he cannot hold the slaves in slavery. When the slaves get together, that's the beginning of getting out of slavery. Now let us maintain unity.

All we say to America is, "Be true to what you said on paper." If I lived in China or even Russia, or any totalitarian country, maybe I could understand the denial of certain basic First Amendment privileges, because they hadn't committed themselves to that over there. But somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read of the freedom of the press. Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for right. And so just as I say, we aren't going to let any injunction turn us around. We are going on.

It's alright to talk about "long white robes over yonder," in all of its symbolism. But ultimately people want some suits and dresses and shoes to wear down here. It's alright to talk about "streets flowing with milk and honey," but God has commanded us to be concerned about the slums down here, and his children who can't eat three square meals a day. It's alright to talk about the new Jerusalem, but one day, God's preacher must talk about the New York, the new Atlanta, the new Philadelphia, the new Los Angeles, the new Memphis, Tennessee. This is what we have to do.

Now, let me say as I move to my conclusion that we've got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point, in Memphis. We've got to see it through. And when we have our march, you need to be there. Be concerned about your brother. You may not be on strike. But either we go up together, or we go down together.

Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge to make America what it ought to be. We have an opportunity to make America a better nation. And I want to thank God, once more, for allowing me to be here with you.

Well, I don't know what will happen now. We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. So I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

At the end of the video you can see King let go of the podium, unsteady on his feet, and his friend has to hold him up so he doesn’t fall over.

I would encourage you to read the entire speech, there are many more important moments, especially about King’s religious faith. But these words echo loudly in my ears today:

America: be true to what you said on paper.

We’ve got some difficult days ahead.

And I want you to know that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.

Either we go up together, or we go down together.

This is so beautiful, Sharon. It may very well be my favorite thing you’ve ever written n here, and that’s saying a lot. We’re all needing encouragement today and thank you for giving us this, first thing in the morning.

Thank you for sharing this, my heart needed these words of encouragement today.