The Theft That Built a Nation

The story of Black land loss—and how generations of stolen acres shaped America’s racial wealth gap.

At the close of the Civil War, Black freedmen spoke with Union military officials who famously promised “40 acres and a mule.” Following emancipation, Union General William T. Sherman signed Special Field Order 15, declaring that 400,000 acres of land in South Carolina would be divided among the formerly enslaved. But the order was rescinded by President Andrew Johnson. Formerly enslaved Black people in America would be starting from nothing.

Upon being freed, they turned to agriculture. Millions of Black people had no choice but to enter into exploitative sharecropping arrangements, working the land in exchange for a small share of the crops. White landowners’ contracts were often designed to keep Black sharecroppers trapped, bound by a debt they couldn’t escape. This is why sharecropping is sometimes called “slavery by another name.” It took decades to overcome a system that was set against them, but eventually, Black people began buying property of their own. Black ownership of farmland had a meteoric rise, peaking in 1910, with estimates ranging between 12.8 million and 16 million acres. In 1920, The New Yorker reports, “African Americans, who made up ten per cent of the population, represented fourteen per cent of Southern farm owners.” But throughout the 20th century, rampant racism against Black farmers at the local and federal levels led to land theft of massive proportions.

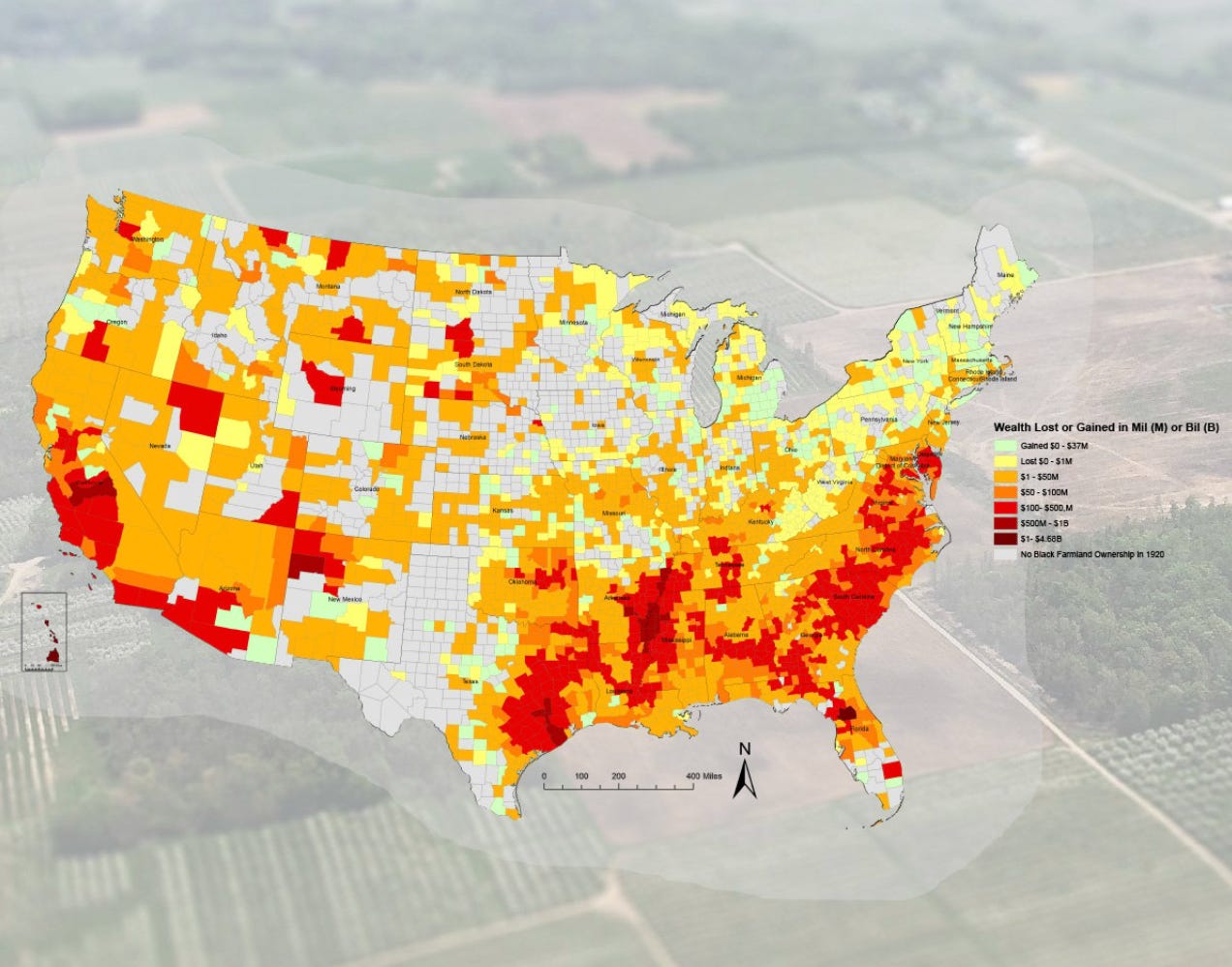

Between 1910 and 1997, Black farmers lost more than 90 percent of their land.

The American Bar Association gathered experts to calculate the total value of Black farmers’ land loss during this period; they arrived at a conservative estimate of $326 billion. “To put this figure in perspective, if this represented the gross domestic product (GDP) of a country” in 2020, Black Americans’ wealth would’ve been in the top 20% — ranking “ahead of South Africa, Finland, and New Zealand.” But as it stands, Black Americans today have 85% less wealth on average than white Americans. One of the researchers, Nathan Rosenberg, told a journalist from The New Yorker, “If you want to understand wealth and inequality in this country, you have to understand black land loss.”

Systemic racism

Even when Black farmers could buy their own land, it was very difficult to keep ownership of it. According to the American Bar Association, “in addition to theft by state-sanctioned violence, intimidation, and lynching, Black farmers also lost land due to discrimination by banks and financial institutions.” Loans were controlled by bankers and federal funding was typically channeled through local committees and southern elected officials, meaning white southerners held the purse strings. By denying federal farm benefits to Black land owners, they could directly benefit white farmers in the community. And if discrimination impacted Black farmers so badly that they eventually had to sell their land, that directly benefited white farmers, too.

Farming is a zero-sum game — not just in competing for the land itself, but in competing for federal funding, too. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the arm of the federal government that provides aid to farmers, playing an especially important role since the 1930s.

“After the New Deal, the USDA became more involved in managing crop prices through subsidies and helping farmers weather price changes with loan and credit programs,” explains FoodPrint, a nonprofit focused on food production practices. These USDA supports “eventually became an integral part of farm survival.”

The problem is, Black farmers have consistently received less aid from the USDA than white farmers: “In 1965, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights determined that the USDA’s loan programs had discriminated against Black farmers, leaving them out of payouts that their white counterparts had received.” This was no accident. USDA agents often colluded with white bankers and farmers, creating arrangements from which they all stood to benefit.

Time highlights the unique challenges of being a Black person in the rural south. “Traditional civil rights narratives have typically centered urban spaces like Atlanta, Birmingham, or Memphis. Yet even as the civil rights revolution brought significant gains to Black residents of those cities, the story was very different in rural places.” The high racial tensions of the civil rights era extended to rural areas, but the gains won in larger cities did not. Racist white people who were upset by racial progress were doubly committed to finding ways to hinder Black advancement. “Land loss was one of these [tactics].”

The single greatest cause of Black involuntary land loss is a policy called heirs’ property. If a landowner dies without a will, their land is automatically passed down to their heirs. Black Americans were distrustful of the white southern court system and had reservations about creating wills or signing any documents that could work against them. Instead, they considered heirs’ property — which involves the legal system minimally and does not require a formal contract — the safest way to keep their land with their descendants.

But in practice the exact opposite happened. The land did not stay with their heirs — nearly all land owned by Black people has been taken because of this policy.

Heirs’ property is complicated because, as FoodPrint reports, “as time goes on, every additional descendant of the original deed holder — every new grandchild or great-grandchild — also qualifies as an heir and part-owner.” The property is jointly owned by an ever-increasing number of heirs. Here’s the kicker: “Without a clear title that ascribes ownership of the land to a single farmer, land managed as heirs’ property cannot qualify for federal aid programs.” Heirs’ property misses out entirely on aid from the USDA, which modern farms cannot survive without. With mounting costs and taxes, a forced sale becomes inevitable — and predatory buyers readily snatch up land at below-market value.

Pigford v. Glickman

The USDA has long subjected Black farmers to more loan delays and denials — both of which give farmers no choice but to enter into high-interest bank loans in order to buy needed supplies like seed and fertilizer ahead of the growing season. Delays and denials have a snowball effect. When Black farmers receive less USDA aid and have to take on more high-interest loans, payments are more costly, making farmers more reliant on loans. This is reflected in their credit history, which makes them less likely to be approved for future loans. After it was proven that Black farmers were systematically discriminated against in 1965, the USDA created a civil rights office for dealing with discrimination claims. The office was shuttered by the Reagan administration, however, and wasn’t reopened until 1996 under Clinton. Few claims were resolved until, in 1999, thousands of Black farmers jointly sued the USDA.

The class-action lawsuit Pigford v. Glickman vindicated thousands of Black farmers. Black farmers who had unresolved discrimination claims against the USDA could settle for upwards of $50,000 if they had sufficient proof that loan delays hurt their farm. The case primarily dealt with discrimination between 1983 and 1997, and the total payout was more than $1 billion, to more than 15,000 farmers who could prove discrimination. A decade later, in 2010, Pigford II brought justice for farmers who missed out on the first case. Another 17,000 claims were settled, for more than $1.25 billion. At more than $2.25 billion total, Pigford I and II were the largest civil rights settlements in history. Though some misleadingly called them a handout, the payout for any single farm wasn’t nearly enough to make up for the decades of discrimination.

Racism persists today

There are one million fewer Black farmers today than there were a century ago. Forty-five thousand Black farmers remain, making up 1.3% of American farmers. Former Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack pointed out that initially, only 0.1% of Covid farm aid went to Black farmers — one-thirteenth of what would be proportionate — and 99% went to white farmers. Then, in 2021, Congress passed a $5 billion targeted debt-relief package for Black farmers in an attempt to lessen racial inequities. But it was shut down by a lawsuit alleging that white farmers were being discriminated against, so in 2022, a $2 billion race-neutral program for all “financially distressed borrowers” was created in its place. This significantly decreased and diluted the aid for Black farmers.

Even now, there are major racial disparities in how USDA aid is distributed. NPR analyzed USDA data to find the racial breakdown of acceptance, rejection, and withdrawal rates for direct loans. “Direct loans are supposed to be among the easiest to get at USDA,” it explained. “They are meant for farmers who can’t get credit elsewhere.” But because of the snowball effect, discrimination in the past creates grounds for disparities in the present. In 2022, the acceptance rate was only 36% among Black farmers. White farmers had twice the acceptance rate, at 72%. Black farmers’ applications were rejected four times as often as white farmers’ (16% vs. 4%) and withdrawn twice as often as white farmers’ (48% vs. 24%).

The USDA is no longer acknowledging or addressing its racist history. FoodPrint writes, “The second Trump administration has declared that the USDA has ‘sufficiently addressed’ its history of racial discrimination.” The Trump administration has taken hard stances against DEI, and the USDA is not exempt from these changes. All USDA efforts to specifically support Black farmers were shut down — though it’s not clear how these persistent racial disparities could be lessened through race neutrality.

A 2010 law, the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act (UPHPA), has been introduced in 26 states and Washington, DC, to protect heirs’ property, though it would need reform to truly protect the most vulnerable farms. Thankfully, nonprofits are standing in the gap and taking on the work of protecting Black landowners’ property. The Center for Heirs’ Property is working to prevent Black land loss. This is important given that, according to The New Yorker, “76% of African Americans do not have a will, more than twice the percentage of white Americans,” and even today “heirs’ property is estimated to make up more than a third of Southern black-owned land — 3.5 million acres, worth more than $28 billion.”

At the close of the Civil War, when Sherman met with Black leaders representing freed Black people, Garrison Frazier said, “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land” and “reap the fruit of our own labor. ” If asked today, many Black Americans would reiterate some version of this same goal.

Marie, I always learn so much from your articles. I did not know about this land loss, and it reminds me of learning about red-lining for the first time in 2020. These are the kinds of things that people should be so much more aware of to help understand systemic racism and its continuing effects.

The headline made me think that this was going to be about taking land from Indigenous people. How tragic that American lands have such a history of repeated theft and displacement of non-white people.