The Story Christian Nationalists Don’t Want You to Know

Black spiritual traditions helped build America—and they’ve always defied a single, state-sanctioned faith.

A national poll recently confirmed that over a quarter of Americans mostly or completely agree with the idea that the US Government should declare America a Christian nation. One in every five believes that God has called Christians to exercise dominion over all areas of American society. This pervasive myth and the political movement that propagates it (Christian nationalism) have become increasingly prominent in political discourse. Adherents of this ideology want to enforce a rigid, singular religious identity that erases the true diversity of faith among the communities that built this country. One of the most prominent of these groups is the enslaved Africans who carried their religions across the Middle Passage and used them as a blueprint for survival and revolt.

The reality is that the Black spiritual tradition in America is a story of brilliant syncretism. Like the country itself, the spiritual practices of Black Americans blended cultures from around the world as ancient African rituals became disguised within the religion of the Europeans who held them in bondage.

The rich traditions of the motherland

A common narrative of enslaved Africans becoming Christian is that they arrived with a clean slate: they pretty much had no real religion and then received the “gift” of a new faith from their masters. This is a lie. The millions of people stolen from West and Central Africa—from the Yoruba, Igbo, Kongo, and countless other nations—were not a monolithic, godless group. They were religiously diverse and deeply steeped in African traditional religions (ATRs) as well as Islam and, to a lesser extent, Portuguese-brought Catholicism.

Surprisingly, the enslavers did not prioritize immediate conversion. For decades, many viewed Africans as too animalistic and not human enough for Christianity. This changed largely when missionaries and plantation owners realized the immense utility of a religion that preached obedience and subservience.

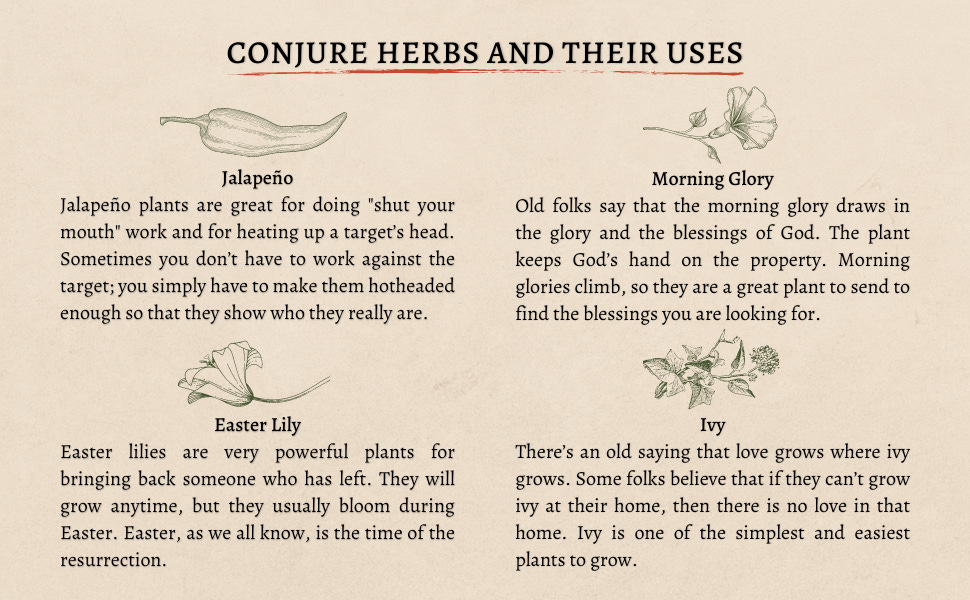

At the same time, enslaved peoples sought to keep their traditions alive regardless of what they were told. Their spiritual traditions, often named collectively in the US context as “Hoodoo” or “Conjure,” centered on herbs, the power of the spoken word, and a deep reverence for ancestors. It was a practical, day-to-day spirituality designed to navigate the challenges of captivity.

How traditions survived

The adoption of Christianity was, for many, less an unquestioning theological conversion than a calculated political strategy. As Conjurer and Herbalist Gerard Miller noted, Black people were never “ones to let good technology go to waste.” When this nation was established, assimilating, at least cosmetically, gained them a critical benefit: the ability to congregate.

The Black church, born in hush harbors and secret riverside meetings, became the ultimate spiritual cloak. They incorporated their ring-shouts, their stomps, their call-and-response, and the power of possession (all being African elements of worship) and transformed them into gospel music and the Holy Ghost falling on a Sunday morning. And while many Black people did eventually embrace Christianity, for many others the Africanisms that white society criminalized were simply syncretized, surviving in plain sight.

When a Black preacher was “whooping“ and calling down the Spirit, the audience was experiencing a form of possession recognizable to practitioners of ATRs, associated with the energy of orishas (Yoruban deities) or other ancestor spirits. When a grandmother taught her children about the power of the broom (sweeping out negativity from one’s house at the end of the year) or the necessity of black-eyed peas on New Year’s (West Africans considered them a charm to repel evil spirits), she was passing down fragments of Conjure, beliefs designed for protection and fortune, disguised as simple “superstitions.”

This strategic blending was a brilliant defensive move. Hoodoo was, in fact, the first African American religion, existing long before mass conversion to Christianity. It was swiftly criminalized, however. Drums were banned after the Stono Rebellion of 1739, the largest slave uprising in the British mainland colonies. During the revolt, enslaved people used drums to coordinate their movements, using specific rhythms to mimic speech patterns and send coded messages. This was a clear link to African spiritual and martial practices. The early “witch trials” in the Americas, unsurprisingly, often targeted Black and Indigenous people.

When African faiths declared war

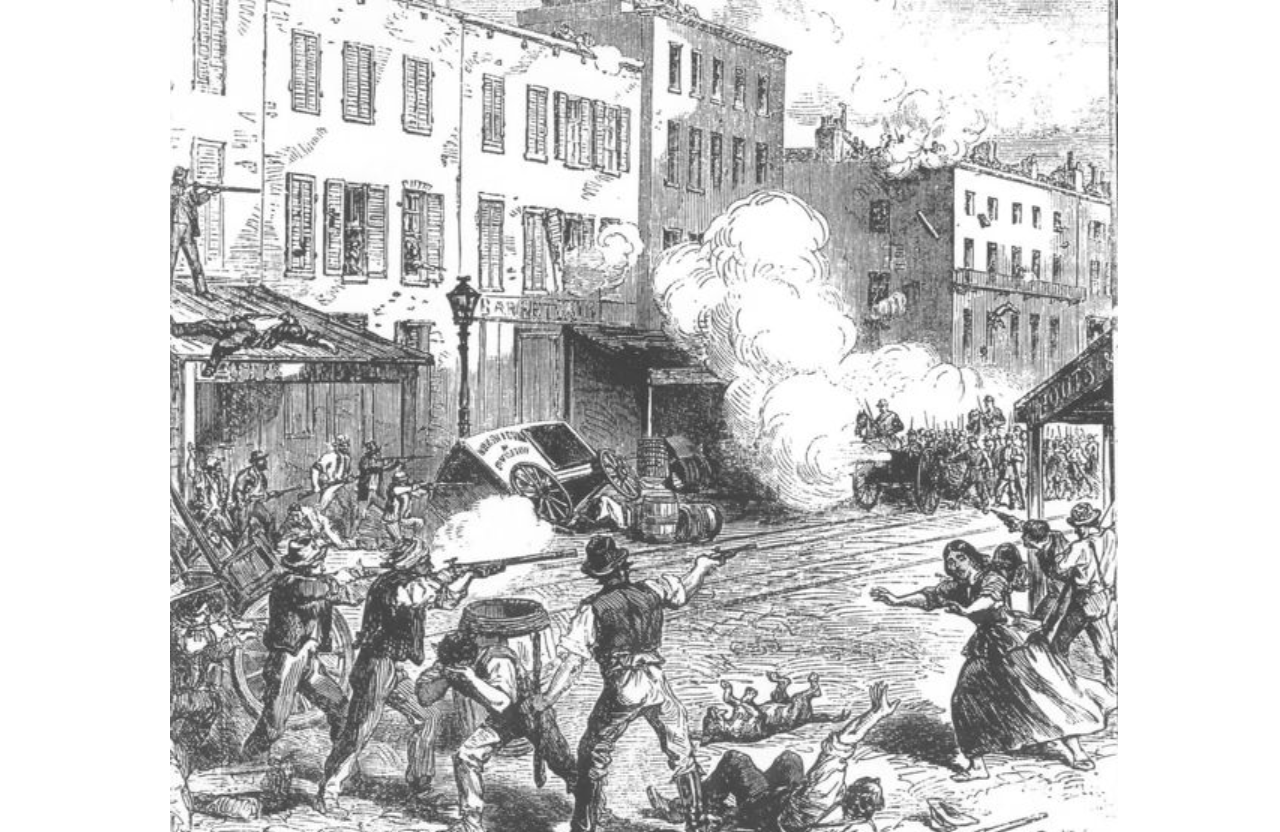

To see the full, terrifying power of these hidden faiths, we must look at the moments they dropped the cloak and became the explicit engine of mass revolt. In 1712 New York City, a time when the North was still deeply reliant on slave labor, a group of primarily African-born enslaved people executed a daring plot. Armed with guns and hatchets, they set fire to a building on Maiden Lane and ambushed the white colonists who ran to extinguish the blaze. Nine white people were killed, and the reprisal was brutal: over 21 slaves were executed, some burned alive or broken on the wheel.

Crucially, contemporary accounts record the insurgents’ call to arms as an explicit “war on Christians.” It was not just a class or labor uprising; it was a spiritual declaration of war. This revolt, fueled by the African-based communal and spiritual traditions that flourished outside the church, demonstrated a clear, organized rejection of the entire Christian colonial structure. Colonial authorities reacted by banning any gathering of more than three slaves, explicitly recognizing the group and the spiritual practices that united them as the true threat.

The ultimate realization of this spiritual power, however, occurred in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, soon to be Haiti.

The Haitian Revolution, the only successful slave revolt in modern history, was not simply a political or military event; it was consecrated by Vodou. In August 1791, Dutty Boukman, a houngan (Vodou priest), and Cécile Fatiman, a prominent mambo (priestess), coordinated the Bois Caïman ceremony. Under a fierce thunderstorm, they gathered approximately 200 enslaved people. They invoked the spirits—the iwa—and swore an oath, drinking the blood of a pig. The ceremony served as the spiritual and strategic launchpad of the revolution.

Vodou provided the religious justification for the revolt. It established a communal, African-centric identity that superseded the differences of the various ethnic groups and the divisive tactics of the French. Where the Christian masters preached submission to a white God, Vodou offered a direct line to African ancestors and powerful spirits of justice, war, and protection. Boukman’s invocation was clear: the God of the enslaved had ordered them to take up arms, and the iwa would protect them. Their faith became an unshakable source of identity, resilience, and military cohesion that the French forces could neither comprehend nor defeat.

Alive and well in the modern world

Fast-forward to today, and we see a resurgence of interest in African diasporic traditional religions like Ifá and Vodou, popularized in recent decades by figures from Zora Neale Hurston to Beyoncé. For many Black Americans, however, the connection is far more intimate and generational.

We are generations deep in spiritual double consciousness. We believe ourselves disconnected from our roots, yet many of us have family altars filled with ancestor pictures, use objects for protection, and practice rituals around food and healing that are rooted directly in Conjure. When an Ifá priestess speaks of the orisha Osun, the goddess of sweet water, love, and fertility, and you remember your grandmother dreaming of fish when someone was pregnant (African American folklore tells that fish in a dream signals a coming birth), you realize nothing is new. We are simply uncovering what was successfully hidden.

This historical reality directly undermines the goals of Christian nationalism. The attempt to impose a culturally white Christianity requires the complete erasure of the spiritual landscape that gave Black America its language of resistance and resilience.

Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors has spoken of her work as a spiritual fight and draws on her ordination in Ifá. She stands in a 400-year-old tradition of using African spiritual principles to dismantle systemic oppression. This is the ultimate rejection of the idea that Black people were passive recipients of faith. They were, and remain, active shapers of a spiritual tradition that is fundamentally anti-oppression.

The fight against Christian nationalism is a fight for religious pluralism, one that recognizes the Black experience as proof that American faith is not, and has never been, a single, monolithic thing. It is woven with the threads of the transatlantic slave trade, where African resilience, through survival within and beyond the Black church, became the holy, unshakeable ground of liberation.

Thank you for this piece, Kahlil. The history of syncretism and spiritual resistance is something that deserves far more attention, and I learned a lot this morning.

What strikes me reading this is how declaring an official religion would require erasing not just Black spiritual traditions, but the very principle that brought so many people to these shores in the first place. The irony has always been there: religious outcasts fleeing persecution who then turned around and persecuted others. But we’ve also always had leaders who saw that hypocrisy clearly and fought against it.

Here’s what I can’t reconcile about the Christian nationalist position: if you’re already a Christian, you have the community, the fellowship, and (if you believe) the benefit of being right with God. That’s enormous. So why do you need the government picking winners and losers based on personal relationships with the divine? The same people who distrust government involvement in their daily lives want that same government enforcing control over the most intimate realm of human experience: our thoughts about existence and meaning? How does that skepticism suddenly disappear when it comes to faith?

This has me thinking about whether a constitutional amendment clarifying religious protections could actually work. Something that gives religious communities what they legitimately want (protection from government interference in their practice) while making crystal clear that no faith gets state sponsorship. The founders knew state-sanctioned religion corrupts both the state and the religion. What would an amendment look like that fixes this tension in a way that even devout Christians could support? It’s something I’m now planning to explore (thanks to Kahlil’s essay) in my newsletter series “A New Bill of Rights,” which looks at constitutional reforms that might actually heal some of our democratic dysfunction.

Off the top of my head, what if an amendment included language like: “No level of government shall establish, endorse, or show preference for any religion or religious denomination over others, nor for religion over non-religion or non-religion over religion.” That clarifies things for everyone: believers of all stripes and non-believers alike.

But to get buy-in from religious communities, you’d want to pair it with something like: “The right of individuals and religious institutions to practice, express, and live according to their faith shall not be infringed, nor shall any person be compelled to participate in religious exercise against their conscience.” Maybe even: “Religious organizations shall retain the right to govern their internal affairs, doctrine, and membership according to their beliefs without government interference.” But maybe we need a caveat in there about not allowing religious leaders to be put in positions of absolute trust with children, because people below the age of consent often get lost in these debates. Everyone should have the right to leave a religion if they want to, no matter how young they are. But the exact wording would be tricky. Lots to think about!

The idea is that you’re trading state endorsement (which corrupts faith anyway) for ironclad protection of actual religious practice. Most Christians I know don’t actually want the government running their church; they want to be left alone to worship freely. An amendment like this gives them that guarantee in permanent ink while making clear the government can’t play favorites. Seems like a fair deal to me.

This essay has genuinely inspired me to start drafting on this question. Thank you for that, Kahlil.

I'm truly for what you are saying about the early religions of the Blacks as being anti-oppression ,especially that which will counter the narrow-minded and bigoted view of Christian Nationalism , but you will certainly know when I say that anything that is counter to many denomination's view of Christianity, will be construed as demonic and will be summarily condemned as heretical ,unacceptable and ungodly .

To me, the commonality of most religions is to treat others like we all like to be treated ourselves and move on from there in keeping the separation of church and state intact within our government, while suggesting the same of other governments , as well.