The Silent Sentinel

The story of how a statue meant to celebrate freedom became a question we still haven’t answered.

She still stands in the harbor, watching. Each morning, she greets the ferries that paddle past at her feet and stands in a stately repose for the tourists who want a photograph. Her face is emblazoned upon coin purses and snow globes, 1,000-piece puzzles and fuzzy socks.

From below her skirts, it’s easy to mistake her for a statue about the triumph and victory of America.

But she has never been a monument to the powerful. Instead, she is a mighty symbol to the powerless.

Today, asylum seekers sleep on sidewalks in the shadow of her torch. They come with blistered feet and children in their arms. They arrive to find chain-link holding pens, buses to distant locations, and governors boasting about how many migrants they have shipped that month, as though they are heads of cattle. Headlines use words like invasion. Politicians speak about them as if they are a natural disaster, not human beings.

And yet there the Mother of Exiles stands, now a great, green contradiction, still facing the sea.

What does it mean to be the country whose most recognizable figure was formerly in bondage? What did Emma Lazarus mean when she wrote, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free?”

These questions have echoed across nearly 140 years. They rang out when ships crowded with Jewish refugees were turned away from our shores. When Japanese Americans were incarcerated behind barbed wire, when we denied Chinese immigrants entry, when we told America that Haitian migrants were eating their pets, when we sent Afghans to whom we had promised assistance back to the Taliban. It rings now, in the swampy prisons that disappear its inhabitants and in seats of airplanes into which we strap unaccompanied children.

We must decide anew whether the light in Lady Liberty’s hand belongs to all, or only to some.

She was born from abolition

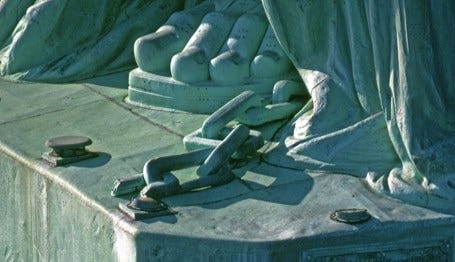

When the idea for Liberty Enlightening the World was first proposed, the Civil War had only just ended. Abraham Lincoln was newly martyred, the country newly sutured, and the world newly watching. The man who conceived of her was a French abolitionist who believed the end of American slavery marked a victory not just for one nation, but for human dignity itself. A woman, robed and unbowed, her torch aloft, her foot breaking the last shackle of bondage.

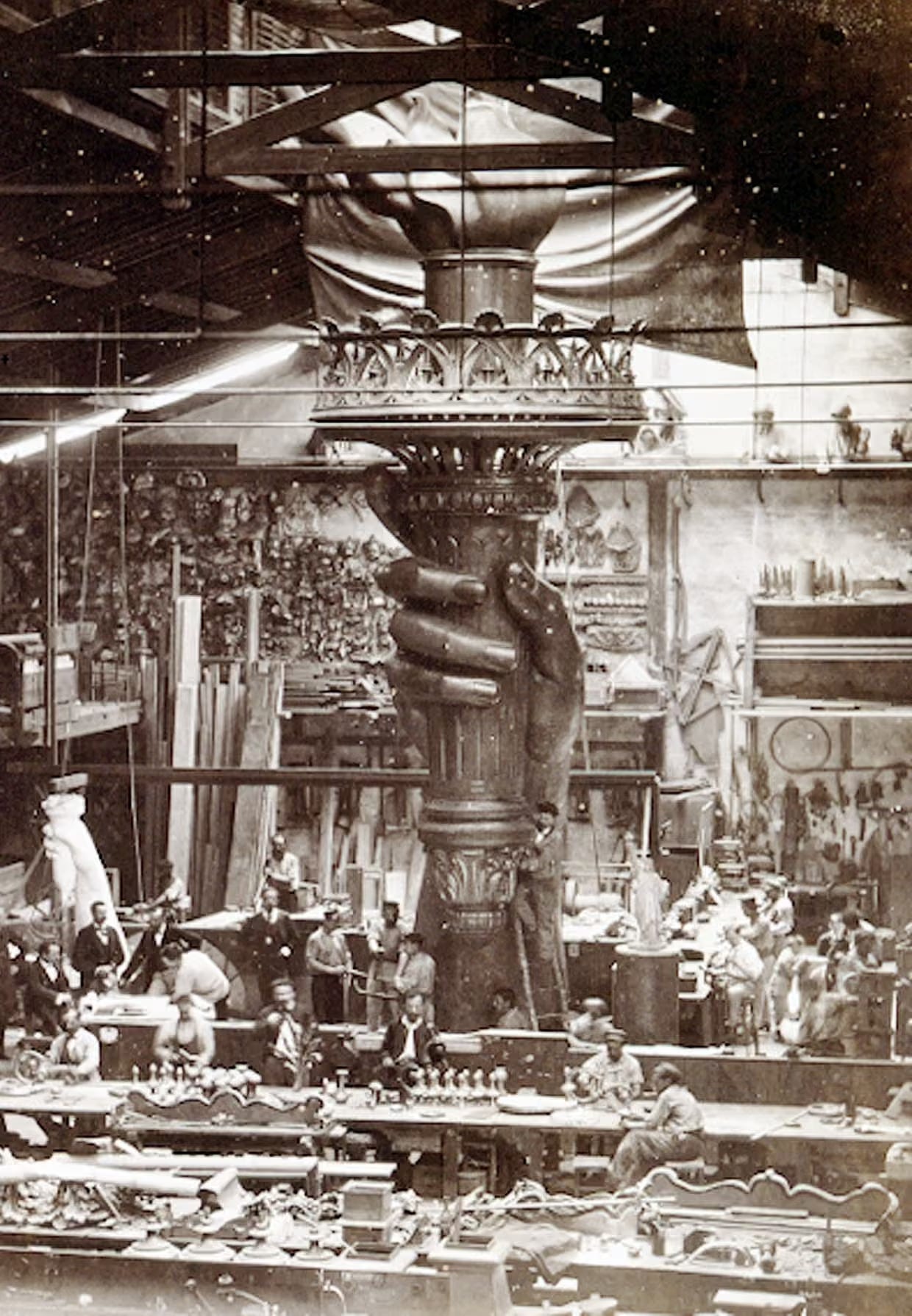

Her copper body was hammered into shape by hand, and the people who made her were tradesmen and apprentices, not aristocrats. They raised money through village fairs and public subscriptions. Schoolchildren contributed coins. The sculpture was not bestowed as a gift from one government to another; she was a collaboration between citizens who believed that freedom, fragile as she may be, could be shared.

By the time her torch was ready to cross the Atlantic, America’s Reconstruction was collapsing. The promise of racial equality was being strangled by the same hands that had once defended enslavement. And yet this statue, designed to celebrate emancipation, was sailing toward a country already forgetting what it had fought for.

Congress refused to appropriate the funds for a place for the full statue to sit. Wealthy donors passed. It was immigrants, children, and laborers — people who had little to spare — who finally raised the funds so she could have a base to stand upon. She rose from the generosity of those she was meant to represent.

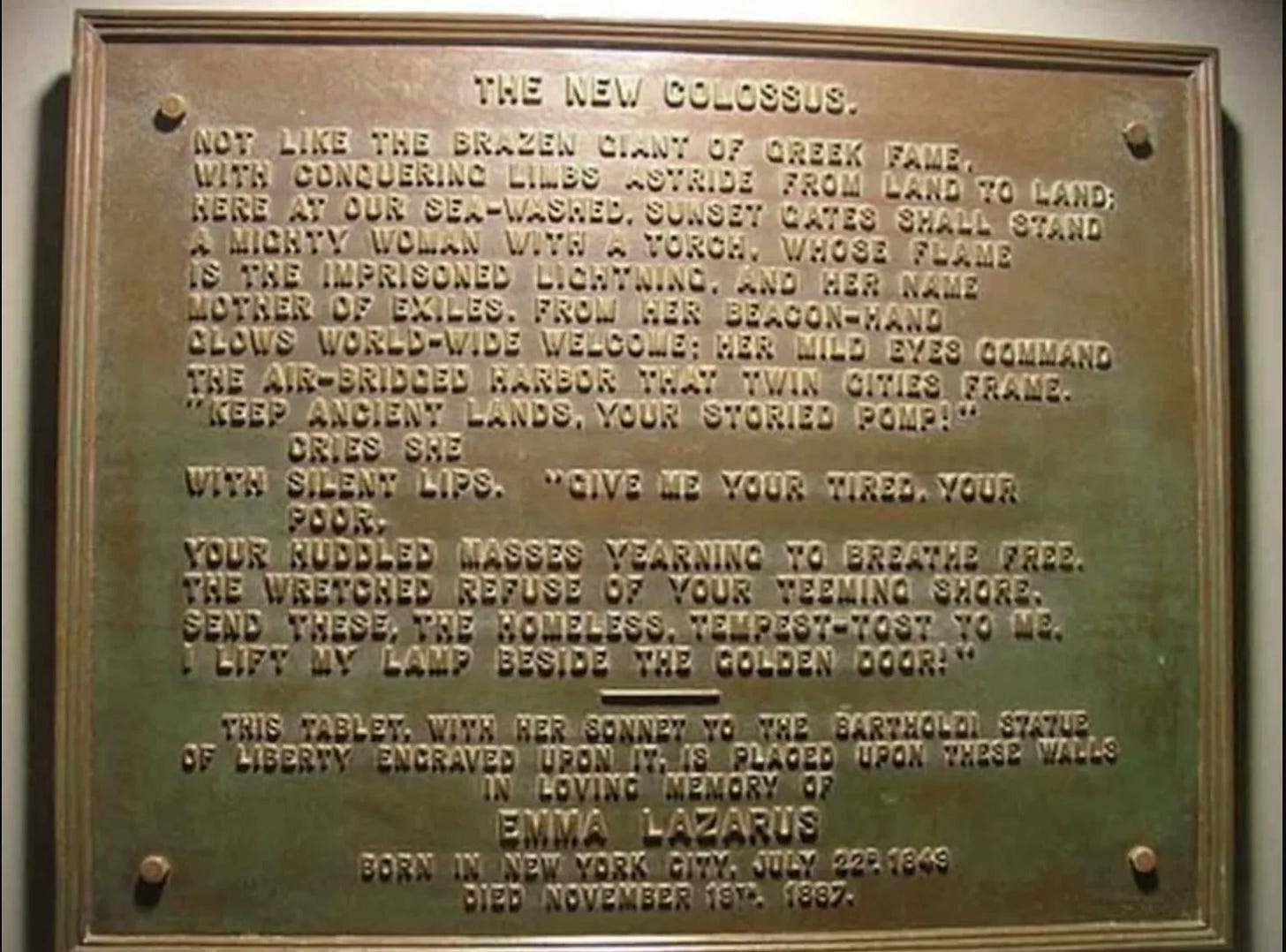

For nearly a decade after she took her place in the harbor, Liberty had no words. She stood, magnificent and mute, until a woman named Emma Lazarus gave her a voice.

Lazarus was born in New York to a wealthy Sephardic Jewish family whose lineage stretched back before the Revolution. She was educated, fluent in multiple languages, and moved easily among the city’s intellectual elite.

In the 1880s, as pogroms raged across Eastern Europe, thousands of Jewish refugees began arriving in New York each month. Lazarus visited the shelters where they slept shoulder to shoulder, where mothers nursed their babies and fathers searched for work in a language they did not speak. She saw in their faces a version of herself, and in their displacement, the long memory of her own people’s exile.

When organizers asked her to contribute a poem to a fundraiser for the statue’s pedestal, she began to imagine what this woman of copper might say if she could speak for herself.

The poem she wrote, “The New Colossus,” rejected the “brazen giant of Greek fame,” the ancient colossus that straddled harbors as a symbol of conquest. Instead, Lazarus offered a new vision:

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles.

No armies beneath her feet. No spoils of war. Only a lamp held high for those the world had cast aside.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp,” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

In those lines, Lazarus transformed the statue’s meaning from empire to empathy, from triumph to welcome.

She understood what so many did not: the greatness of a nation that is not measured by its walls, but by its willingness to open its doors.

And though the poem raised money for the pedestal, it did more than that. It gave Liberty a soul.

Then “The New Colossus” vanished from memory.

Lazarus died the following year, far too young at 38, likely of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. America hurtled into the Gilded Age, into industrial expansion, into the comfortable illusion that liberty was something we already possessed.

When the statue was ready for her moment in the spotlight, the brass bands and the ship horns raised a ruckus, and then the Mother of Exiles stood silent once more.

Eighteen years later, in a Manhattan bookshop, a 60-year-old woman named Georgina Schuyler opened a volume and recognized a name — Emma Lazarus, her late friend. Her eyes stopped at the lines that read more like scripture than verse: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Georgina Schuyler was the great-granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton and Eliza Schuyler Hamilton. She was a descendant of privilege, but her lineage was also traced to one of America’s most famous immigrants. And with her privilege, Georgina Schuyler resurrected the words of a Jewish woman writing for the displaced.

Schuyler led a campaign to have the poem cast in bronze and affixed inside the pedestal of Liberty Enlightening the World. From that moment forward, Lady Liberty spoke with a new voice: the language not of conquest, but of welcome. Her torch was no longer the glow of gilded empire; it was a midnight lantern for the world’s displaced.

The generations that followed turned those lines into liturgy. They were quoted by presidents and protesters, printed in textbooks, recited at naturalization ceremonies.

The plaque still hangs near Liberty’s feet, the edges dulled by salt air and time. But the words are still legible, and they beg the question that America must now grapple with: Do you still mean this?

The promise the statue carried across the Atlantic — that liberty could be shared, that welcome could be stronger than fear — has always been fragile. It was fragile when enslaved people were told freedom was coming but justice could wait. It was fragile when Chinese immigrants built the railroads and were then forbidden to belong. It is fragile now, when politicians speak the language of protection to disguise the practice of cruelty.

We like to imagine her torch as eternal, but it’s not. It burns only because people before us tended it — people with little to give who still gave it anyway, who sent pennies and poems and belief across oceans.

She is not asking to be admired from afar. She is asking for us to tend to the light she holds aloft.

Because if we let liberty’s light go dark — if we decide that some people are too foreign, too poor, or too brown to belong — then we will not be the keepers of liberty anymore.

We will be the ones she pities, the exiles who lost their own way to shore.

You either stand at the door and hold it open for others, or you let it close behind you. May we all aspire to lift our lamps to the golden door for others.

This! This right here makes me so proud to be an American, Sharon. My family came from Ireland, Germany, Lebanon, and I’m not sure where else lol BUT they all immigrated here. And at the time they were the “other”. We do have a history of demonizing the “other”. And yet they were allowed to stay. They were not sent to a swamp prison. And I long and hope that for the future of our country. To allow more refugees and immigrants to arrive SAFELY in our country. And be given the opportunities like all of my family has been given.