The Shutdown and the Dinner Table: A Guide to America’s Food-Assistance System

For nearly a century, federal food programs have promised that no American should go hungry. The shutdown tested that promise.

As Washington’s two parties traded shutdown threats, the real consequences unfolded far from the Capitol. Workers were furloughed, households braced for higher health-care premiums, and food-insecure Americans were suddenly unsure where their next meal would come from.

Overnight, tens of millions of Americans who relied on federal food-assistance programs were told that their November benefits might not arrive. Parents refreshed their EBT (electronic benefit transfer) balances, hoping for deposits that didn’t hit. Grocery trips were postponed. Food-bank lines lengthened before dawn.

The effects hit blue and red states alike. In New York, advocates warned that 1.8 million residents who depend on SNAP (food stamps) could see immediate disruptions. In Texas, caseworkers described parents skipping meals so their kids wouldn’t. At food pantries nationwide, volunteers began rationing donations — stretching rice, canned beans, and baby formula to get through another week.

And the poorest families weren’t the only ones feeling the squeeze.

In places like Fort Stewart, GA, and Camp Pendleton, CA, active-duty military families — often junior enlisted — found themselves caught in the same uncertainty as their low-income civilian neighbors. Nearly one in four military families experience food insecurity in a typical year, and many depend on SNAP or WIC (food assistance for women, infants, and children) to bridge the gap between paychecks and dinner plates. When those benefits stopped, even some of the families who serve the country were left wondering how to feed their own.

For many Americans, SNAP, WIC, and school-meal programs are government acronyms that are too easy to stereotype: distant bureaucracy, rife with fraud, supporting “other people.” But for more folks than you might imagine, food assistance is not theoretical. It is survival.

It is the difference between groceries or hunger — for the single mom working two jobs, the retiree on a fixed income, the toddler in daycare, and the young military couple counting dollars before payday.

Though the scale is modern, the story isn’t new. Food assistance has been woven into American public policy for nearly a century — born of the Great Depression, expanded during the 1960s War on Poverty, reshaped through recessions and globalization. Today it forms one of the most important, least understood pillars of the US safety net.

This explainer traces how three core programs — SNAP, WIC, and the child nutrition programs — came to be; why they exist; and who depends on them now. Because before we debate their future, we should understand their past — and the millions of lives hanging in the balance.

The origins of food assistance programs: from the War on Poverty to today

Although federal nutrition programs may feel like a modern invention — or a recent partisan flashpoint — their roots stretch back nearly a century. They emerged not from abstract ideology but from a straightforward problem: in the United States, millions of people did not have enough to eat, and the market alone would not, could not, fix it.

The earliest federal food assistance began under FDR during the Great Depression, when collapsing farm prices left growers with excess crops even as families went hungry. Washington’s response was both economic and humanitarian: buy surplus food from farmers and distribute it to those in need. This dual purpose — supporting agricultural markets while feeding families — became the DNA of American food policy. From the start, “farm programs” and “hunger programs” were intertwined.

The modern food safety net largely took shape during the 1960s and 1970s. Disturbing reports from the Mississippi Delta, Appalachia, and major cities revealed children suffering from malnutrition, anemia, and chronic hunger. A 1967 Senate investigation described some children surviving on nothing more than “cornbread and molasses.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson made the fight against hunger a pillar of the War on Poverty, arguing that a nation as wealthy as the United States had a moral obligation to ensure its people could eat. Congress followed with sweeping expansions: the Food Stamp Act of 1964 permanently authorized the modern food-stamp program (now SNAP); the National School Lunch Act of 1946 and Child Nutrition Act of 1966 dramatically expanded federally supported school meals; and in 1975 the WIC program began providing targeted nutrition for pregnant women, infants, and young children.

The rationale for the investments was clear. Nourished children were more able to learn; pregnant women with access to healthy food were more likely to have healthy babies; and families with modest incomes could spend more of their pay on essentials other than simply staying fed.

Over the next several decades, these programs grew gradually, powered by an unusual bipartisan coalition. Farm-state Republicans backed nutrition aid because purchasing food supported agricultural producers; urban Democrats backed it because it helped low-income families. This marriage of interests protected food assistance even during moments of retrenchment. When the 1996 welfare reform law sharply curtailed cash benefits, nutrition programs remained largely intact. Even as eligibility tightened and work rules expanded, the core idea — that children shouldn’t go hungry — held broad public support.

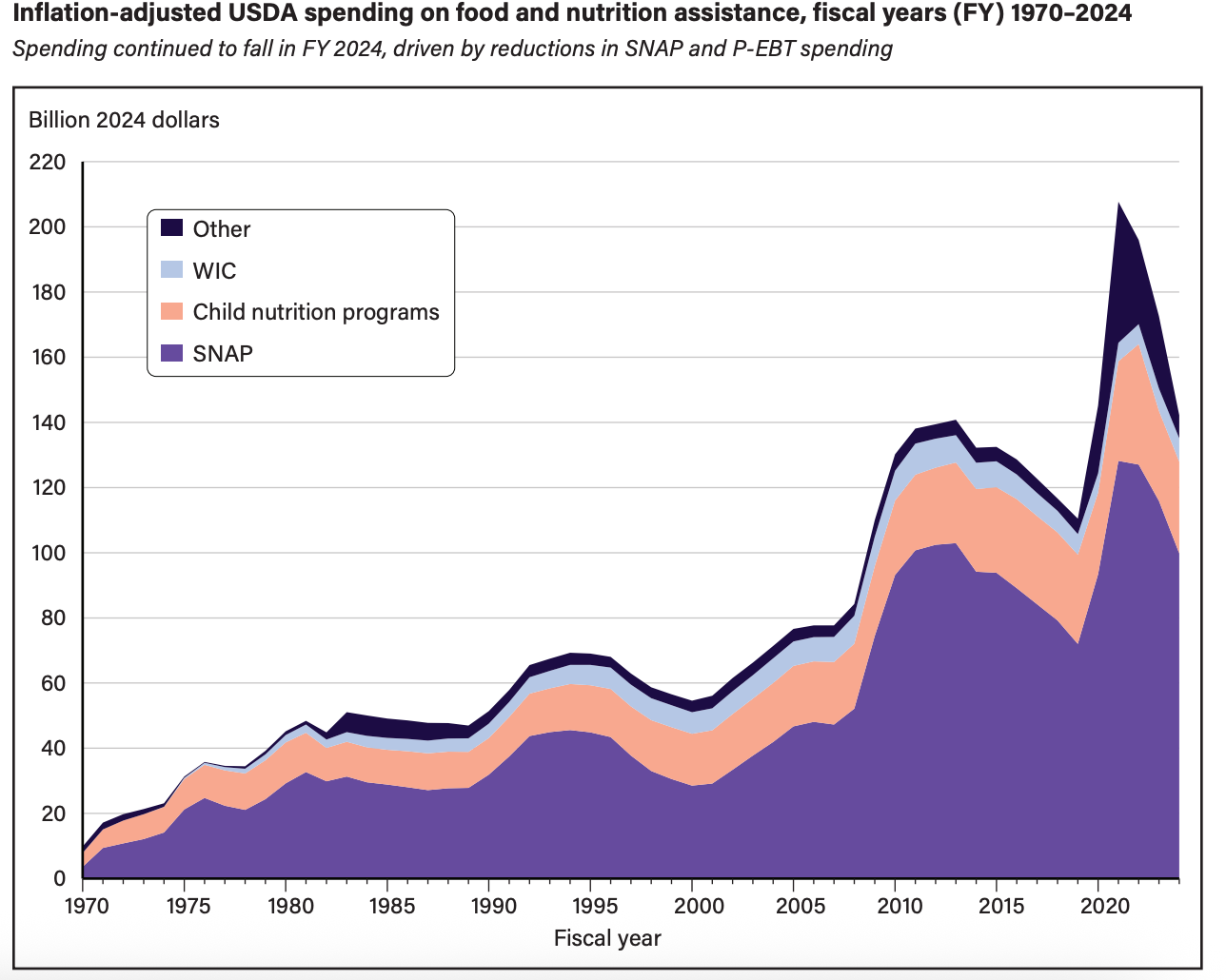

Economic shocks consistently pushed these programs to the forefront. Between 2008 and 2011, during the Great Recession and the years following it, SNAP enrollment more than doubled, helping keep an estimated 4–5 million people out of poverty. The Covid-19 pandemic triggered another sharp rise as schools closed and families lost income; emergency boosts to SNAP, school-meal replacements, and expanded WIC kept food insecurity from climbing nearly as high as expected — clear evidence that when crisis hits, nutrition programs expand quickly to meet increased need.

Across these eras — from crop purchases in the Depression to the War on Poverty, welfare reform, the Great Recession, and Covid-19 — one through-line endures: each generation has reaffirmed that ensuring Americans, especially children, have enough to eat is a basic national responsibility. These programs were not accidents of policy; they were deliberate answers to hunger and broader economic stability among the most vulnerable.

The big three food assistance programs

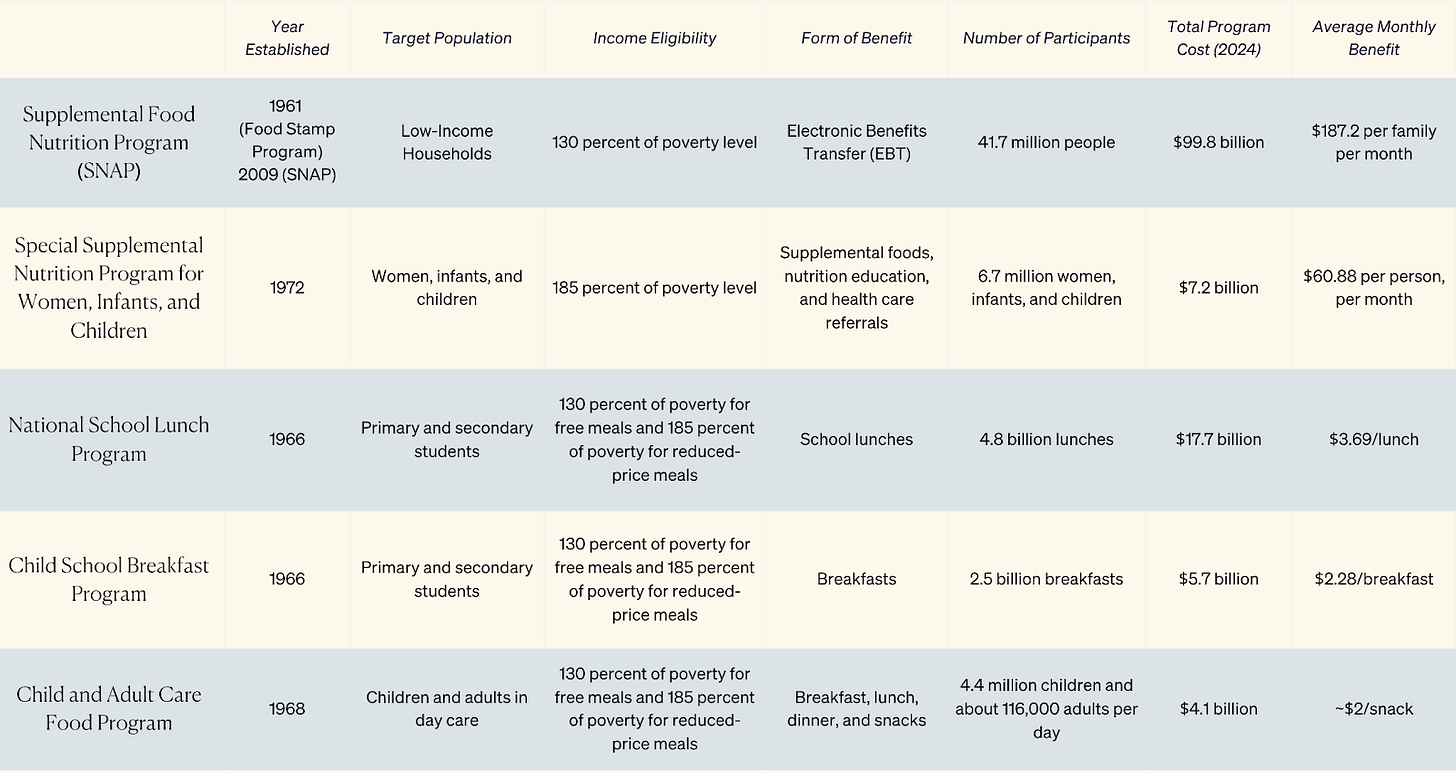

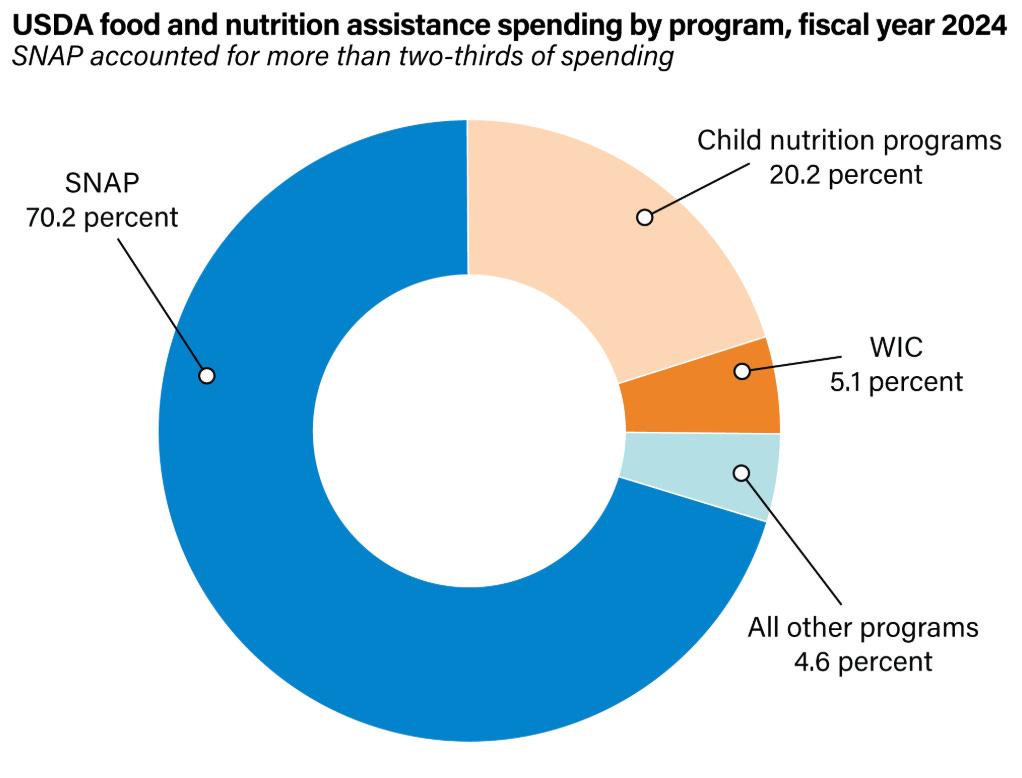

Taken together, three federal nutrition programs account for nearly all US food-assistance spending. Though structured differently, they share the same basic goal: to ensure households — especially children — have enough to eat. In fiscal year 2024, SNAP, WIC, and the child nutrition programs accounted for more than 95% of all USDA food-assistance funding, with SNAP alone making up over 70%.

The backbone of this system is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Today it provides monthly electronic benefits to help low-income households buy groceries at authorized retailers. SNAP served 41.7 million people — roughly one in eight Americans — and cost $99.8 billion in 2024. Eligibility is targeted to households earning 130% of the federal poverty level, and the average monthly benefit is about $187 per household.

Though sometimes described as “welfare,” SNAP is fundamentally a work-support program: most adult recipients who can work do work, and the majority of beneficiaries live in households with children, elderly adults, or people with disabilities. It is the closest thing the federal government provides to a guaranteed food budget.

If SNAP is the foundation, WIC is the targeted intervention. Created in 1972, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) focuses narrowly on pregnant and postpartum women, infants, and children under five — groups especially vulnerable to inadequate nutrition. WIC provides supplemental foods (including infant formula), nutrition counseling, breastfeeding support, and referrals to health care.

Families qualify with incomes up to 185% of the poverty level, and the program served 6.7 million people in 2024 at a cost of $7.2 billion. Benefits average roughly $60.88 per person per month, reflecting the program’s role as a nutritional supplement rather than a full grocery benefit. Decades of research link WIC participation to healthier births, improved childhood nutrition, and lower long-term health-care costs — making it one of the most studied and cost-effective federal programs.

Finally, the child nutrition programs form the third pillar. These include the National School Lunch Program, the School Breakfast Program, and the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) — together serving children where they spend their days: school and childcare. Eligibility is tied to income: children in households below 130% of poverty qualify for free meals; those below 185% qualify for reduced-price meals.

In 2024, the School Lunch Program provided 4.8 billion meals at a cost of $17.7 billion (about $3.69 per meal). The Breakfast Program delivered 2.5 billion breakfasts at a cost of $5.7 billion (about $2.28 per meal). CACFP supplied meals and snacks to 4.4 million children and roughly 116,000 adults daily, at a cost of $4.1 billion — averaging roughly $2 per snack or meal. Together, these programs accounted for about 20% of total nutrition-assistance spending in FY 2024. These meals are the most consistent nutrition many students receive all week.

SNAP, WIC, and school-based programs reflect different ideas about how people go hungry— and how society should respond. SNAP fights household food insecurity by boosting purchasing power; WIC intervenes early to prevent harm; and school-based programs integrate food into the daily structure of childhood. But together, they deliver a single message: in the United States, access to food is a public responsibility, not just a private struggle.

The politics of food assistance

Despite broad public support for helping families put food on the table, federal nutrition programs have long been charged with political meaning — caught at the intersection of cost and ideology. At their core, these programs raise uncomfortable questions about the role of government, who deserves help, and how far the safety net should reach.

Much of the political tension centers on cost and perceived fairness. SNAP alone accounts for just shy of $100 billion annually, making it one of the nation’s largest anti-poverty programs. And while the USDA estimates that roughly 11% of SNAP payments are made in error — a non-trivial share for a program of its size — it is often portrayed as far more abused than the data suggest.

That perception fuels recurring proposals to tighten eligibility, impose stricter work requirements, and shift program control to states. Supporters argue that food assistance is an investment in children and long-term economic stability; critics frame it as dependency and runaway spending. In practice, the disagreement is less about data than about values.

Schools, however, complicate the story. The National School Lunch Program and the School Breakfast Program — together serving more than 30 million children annually — extend food assistance into classrooms, where the moral logic is almost impossible to dispute. Teachers see firsthand how hunger affects learning; principals report calmer classrooms and improved attendance when meals are available. Politicians who would cut SNAP often defend school meals, reflecting the persistent belief that children, at least, are deserving. These programs broaden the network and embed food assistance into daily American life, making it even harder to undo.

Politics also flows through the Farm Bill. It is typically used to reauthorize SNAP, which accounts for about 80% of Farm Bill spending. That structure has, for decades, tied the interests of rural Republicans (who support crop subsidies) to those of urban Democrats (who support nutrition aid), creating a rare bipartisan coalition.

In many ways, the politics of food assistance mirror broader American debates: whether poverty stems from systems or individual choices; whether government should guarantee basic needs; whether helping the vulnerable strengthens society or burdens it. Programs like SNAP, WIC, and school meals have survived because they answer immediate need and deliver measurable benefits.

A century-old promise under strain

For nearly a century, federal food assistance programs have reflected a simple national promise: no one in the United States should go hungry. Today, that promise is under strain. The government shutdown exposed just how many people live close to the edge.

They are not whom stereotypes suggest. They include millions of children; seniors on fixed incomes; working parents earning too little to keep up with costs; and even active-duty military families stationed far from home. The safety net is broad because need is broad.

Politically, food assistance has become a stand-in for larger national arguments about the role of government, fiscal responsibility, and personal responsibility. Critics see runaway spending and dependency; supporters see an essential guardrail against poverty. But beneath the rhetoric is a quieter consensus: when people are hungry, nothing else works — not school, not work, not community life.

Even the fiercest debates of recent years have rarely challenged the existence of these programs — only their size, their rules, or who should administer them. They have survived because, at their core, they do what policy rarely does: they work. But the shutdown’s halted payments showed that a system built over decades can be disrupted overnight — not by lack of need, but by lack of political will.

The United States remains one of the richest nations in history, yet hunger persists. We are confronted anew with old questions: Is access to food a right, a privilege, or something in between? And if we can grow enough to feed the world, why can’t we guarantee food for all Americans?

How we answer will determine whether the programs built to fight hunger endure as a national promise — or fade into a political bargaining chip.

Great article, Casey! Thanks for getting the news out! Wish that everyone understood the importance of these programs!

I somehow ended up on Angel Tree TikTok. It’s usually someone who has the means buying presents for kids off an Angel Tree. There was one video in particular of a family who has four young daughters who listed most of their wants as food and hygiene products bc they literally had so little. For context the kids usually have a few toys listed and one thing they need like shoes or a warm winter coat. The woman who picked this family decided to go all out providing these kids with lots of hygiene items and food to get them through the year, but also reached out to get them some toys.