The Senate Goes Nuclear

Thomas Jefferson was confused.

Just back from France, Jefferson was sitting down for breakfast with George Washington to discuss the US Constitution, which had been written while he was away.

Why, Jefferson asked Washington, did the new legislative branch contain two chambers, both a House of Representatives and a Senate? Why not just the House, the body elected directly by the people? (Senators were originally elected by state legislatures.)

“Why,” retorted Washington, “did you just now pour that coffee into your saucer, before drinking?”

“To cool it,” Jefferson replied. “My throat is not made of brass.”

Exactly, Washington said: “We pour our legislation into the senatorial saucer to cool it.”

At least, that’s how the story goes. It’s not clear Washington ever actually used this famous metaphor. But the anecdote, however apocryphal, does represent the truth about how the Founders viewed the upper chamber. “The use of the Senate is to consist in its proceeding with more coolness, with more system, and with more wisdom, than the [House],” James Madison said at the Constitutional Convention.

This has created a difficult tight rope for the Senate almost since the beginning. How do you balance the chamber’s raison d’être — making sure nothing speeds through Congress too fast — while also ensuring, well, that some things still get done? How do you give a voice to the minority while still letting the majority craft policy? The Senate is constantly debating where’s the right place to draw the line.

Over time, the Senate settled on the filibuster as a tool to strike this balance. In theory, this rule ensures that Senate debate on bills and nominations can be shut off only if at least 60 senators agree. Only a simple majority is needed to actually pass a bill; but to get to that final step, you need to reach a slightly higher, three-fifths threshold.

But, as the decades have rolled on and Washington has grown more polarized, senators from both parties (generally depending on whether they control the majority) have started getting frustrated with the filibuster. Majorities have accused minorities of abusing their cooling power, throwing the Senate into complete standstill rather than settling into a healthily deliberative, but still productive, pace. So senators have started chipping away at the filibuster as a result.

For legislation, it has become the norm to use the reconciliation process to pass large bills with only a simple majority, making an end run around the filibuster. This is how Presidents Barack Obama, Joe Biden, and Donald Trump passed most of their signature pieces of legislation.

For nominees, Democrats changed the Senate’s rules in 2013 to end the filibuster for all presidential appointments except the Supreme Court. In 2017, Republicans expanded that rules change to include the Supreme Court.

Even these exceptions were created through a back door. Technically, changing the Senate rules requires a two-thirds majority, 67 votes. But the 2013 and 2017 senators used a loophole known as the “nuclear option.” Basically, it works like this:

The Senate votes to do something.

It fails to receive the required 60 votes.

The presiding officer says, “Sorry, this action can’t proceed.”

The majority leader says, “Actually, it takes only 51 votes for this type of action to move forward.”

The presiding officer says, “No, it doesn’t.”

The majority leader says, “How about we vote on it?” Changing the Senate rules may take 67 votes, but overruling a judgment of the presiding officer takes only 51.

The Senate overrules the presiding officer, which becomes the chamber’s new precedent going forward. Ipso facto, it now takes only 51 votes to do what the Senate was trying to do.

Last week, the nuclear option was used in the Senate once again, to allow multiple executive branch nominees to be confirmed at once. (Judicial nominees will still have to be voted on one by one.) This week, the Senate will take advantage of the change, confirming 48 nominees in one fell swoop.

Callista Gingrich, wife of former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, will become US ambassador to Switzerland. Kimberly Guilfoyle, ex-girlfriend of Donald Trump Jr., will become ambassador to Greece. And people you’ve never heard of will be confirmed as assistant secretary of the interior, general counsel of the Department of Energy, administrator of the Federal Highway Administration, and other vacant posts. All at the same time.

As always, this rules change stems from a disagreement between the parties about where to draw the Senate’s line between majority rule and minority rights.

In administrations past, many of the nominees at issue were confirmed by unanimous consent, a process that allows something to be fast-tracked in the Senate if no one objects. The Federal Highway Administration chief isn’t normally the type of job that draws very many objections.

But Democrats haven’t agreed to speed through any Trump nominees by unanimous consent, as a way to protest the administration. In Barack Obama’s first term, 90% of his nominees were confirmed by unanimous consent. In Trump’s first term, 65%. In Biden’s term, 57%. So far, 0% of Trump’s nominees have been similarly fast-tracked, and Democrats have signaled no intention to change that anytime soon.

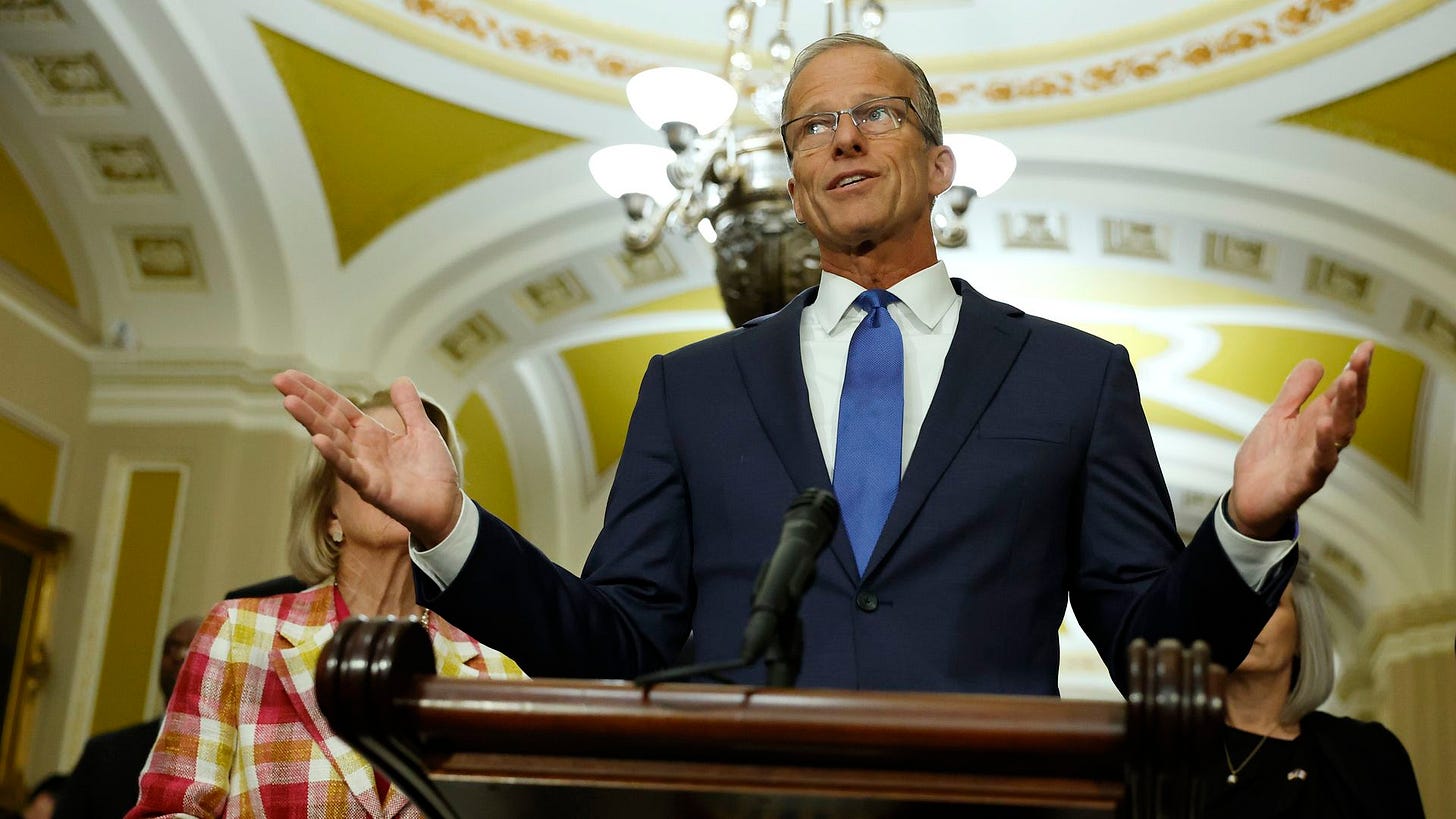

This means that every single one of Trump’s confirmed nominees has had to march through a much slower process, eating up hours and hours of the Senate’s time. As a result, Senate Majority Leader John Thune has complained that the Senate has become a “personnel department.” He’s also noted that, even as Democrats have forced the nominees to go through their full debate time, the nominees themselves rarely get debated. According to Republicans, for almost three-fourths of the Trump nominees so far, Democrats have merely forced the clock to tick through to the end of the required debate time, rather than actually using the opportunity to discuss the appointees in question.

Democrats, in response, allege that Trump’s nominees have been uniquely unqualified and that his administration has attempted to abuse its powers, precluding them from offering the consent needed to speed through any nominations.

But Republicans say the minority has gone too far in using their obstructive powers, just as Democrats said about Republicans in 2013 and Republicans said about Democrats in 2017. With more and more floor time being devoted to nominations — and hundreds of administration spots remaining vacant — Republicans felt the balance between moving slowly and getting things done had, once again, gotten out of whack. So they forced a change.

Before, it would have taken the Senate 96 hours to work through 48 nominees, meaning that if they worked eight-hour days and did nothing but consider nominees, it would have taken them 12 days to get through them. This week, they’ll do it in two hours. There will be no limit for how many executive branch nominees can be confirmed at once through this process.

The “nuclear option” first received its name because it was thought that changing the rules like this, through a loophole, would blow up the Senate.

Nothing would get done again, observers warned: the move would be so toxic that Washington would just shut down in protest.

But that hasn’t really happened.

Instead, each time the nuclear option has been invoked, the two parties have adapted to the new equilibrium. After all, if it becomes easier for a Republican president to confirm his nominees today, it will also be easier for a Democratic president tomorrow. At different points, both parties have dug their heels in, refusing to let nominees go through until the other party changed the rules — and then reaped the benefits of that rules change as soon as the shoe was on the other foot. The same thing is likely to happen here.

It’s probable that this cycle will keep repeating itself until the filibuster is abolished completely, allowing both nominations and filibusters to proceed with 51 votes. At that point, the Senate will become exactly what the Founders feared: a body ruled purely by majority passions, no different from the House.

That is, unless a bipartisan group emerges to try to strike a new balance, to find a middle ground that still lets the minority have a say in Senate business — without letting them abuse that power and slow everything down, no matter what.

This may sound like a fantasy, but it actually happened the first time a Senate majority came close to using the nuclear option, in 2005. At the time, senators like Robert Byrd and John McCain stepped forward to form the “Gang of 14.”

The group included seven Democrats and seven Republicans. Because of the way the Senate was composed at the time, Democratic leaders weren’t able to filibuster any of George W. Bush’s nominees without those seven Democrats — if they joined Republicans in cutting off debate, the 60-vote threshold would be surpassed. And GOP leaders weren’t able to eliminate the filibuster without those seven Republicans — if they joined Democrats in opposing the nuclear option, a potential rules change wouldn’t reach 51 votes.

So the Democrats in the “gang” agreed to filibuster Bush nominees only “under extraordinary circumstances,” pledging to exercise their powers of obstruction “in good faith” instead of against every nominee. In exchange, the Republicans in the group said they would oppose any changes to the Senate’s rules.

“Such a return to the early practices of our government may well serve to reduce the rancor that unfortunately accompanies the advice and consent process in the Senate,” the senators said in a joint statement. “We firmly believe this agreement is consistent with the traditions of the United States Senate that we as Senators seek to uphold.”

Last week, in that spirit, there were last-minute negotiations in the Senate about setting up some sort of bipartisan off-ramp to the nuclear option, which would have allowed the Democrats to retain a foothold in the process while still letting Republicans churn more quickly through nominees.

Unlike in 2005, the two sides failed to reach a deal. The House-ification of the Senate is now moving along accordingly.

What I would actually LOVE to see regarding improving bipartisanship is to 1) eliminate the filibuster and 2) add a new rule that demands bipartisanship. Let’s say 5 (I’m just giving a random number here) senators from an opposing party are required to sign on to any given bill in order to pass. Meaning, they could still have a few senators of their own party vote no, but if they can get senators of other party to vote yes, they can get the bill passed.

I think it may take a little while to get the ball rolling on something like that, since our politics have become so calcified. But if the senate is as adaptive as Gabe claims they are, I think they’d eventually do just that, adapt.

We do not need two Houses, so if it becomes a total houseification, then we might as well eliminate one chamber and save the money. It's absurd if they think the voters will be fine with duplicate dysfunctional chambers. Either one is the brake pedal, or it's no longer useful.