The Racist Reason Why You Can’t Eat Nature’s Free Food

A forgotten history of how America criminalized foraging—and how those laws still enforce hunger and dependency.

After SNAP benefits paused on November 1, almost 42 million Americans lost financial support for buying groceries, and food banks across America saw the length of their lines grow. The San Antonio Food Bank was scrambling to serve 170,000 people, up from their usual 120,000. Eric Cooper, the food bank’s president, had to recruit 150 additional volunteers just to manage the crowds, and he told reporters that he had a little less than four weeks’ worth of inventory left. The crisis had left many wondering how a nation with such abundance can still let millions go hungry.

What if a partial solution to hunger — both now and in the future — has been growing around us all along? In public parks across the same city of San Antonio, mesquite pods rot on the ground. Prickly pear fruits (each serving containing more than one-third of daily vitamin C needs) shrivel unpicked. Around the city, and many cities like it, food grows freely.

The only issue is that the State of Texas considers it stealing to harvest this food without permission.

For over a century, anti-foraging laws have drawn invisible lines around who’s allowed to live off the land and who’s punished for trying. Here’s the nefarious origin of these policies.

“You can’t starve a negro”

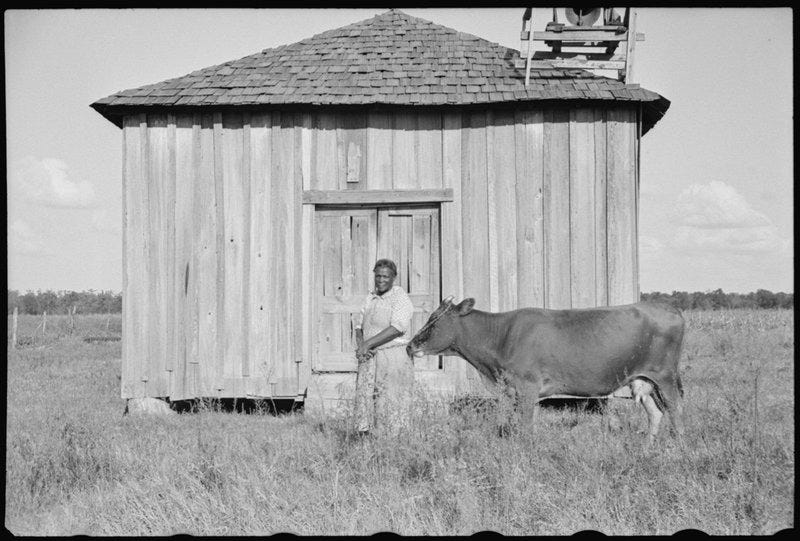

Last week, I stood at Mount Vernon for the premiere of Ken Burns’s new documentary series about the American Revolution. During a tour of the estate, a historian mentioned, almost in passing, that George Washington was accused of underfeeding his enslaved workers. “They survived,” she said, by foraging: “hunting small game, gathering berries, and fishing the Potomac.” Planters like Washington discovered they could shift food costs onto the enslaved themselves, who would collect food before their workday in the fields. Archaeological evidence from slave quarters shows wild game bones, fruit pits from foraged trees, and shells from gathered mollusks.

The enslaved built an entire parallel food system based on what was abundantly available around them, oftentimes incorporating the learning of surrounding Indigenous tribes. Notably, the earliest anti-foraging laws in the New World were directed at Indigenous peoples as a tool of colonialism and land control.

Shortly after English arrival, settlers systematically pushed the Powhatan Tribe off their traditional foraging grounds and used the threat of armed violence to enforce this displacement. The hunting and gathering practices of many Native Americans were often used to justify driving them from their historic lands under the argument that they had inadequately utilized the land. The precedent established the restriction of foraging as a powerful means of dispossession and assimilation.

This pattern would also be used against newly freed Black Americans after, in 1865, planters suddenly faced a crisis: freed slaves no longer needed them.

A Fluvanna County, VA, planter complained in 1877 that his Black neighbors lived by hunting, fishing, and “gathering berries and sumac,” only occasionally working for wages. In Tidewater, VA, Black labor vanished during fishing season. In the Natchez district, “a quarter of Black men and women worked for wages no more than six weeks each year.” The planters’ own words reveal their panic. “Good fruit years demoralize the Negro more than anything else,” one wrote. Frances Butler Leigh, a Georgia planter, lamented what she called a well-known fact:

“You can’t starve a negro.”

The solution was swift and harsh. Six southern states criminalized trespassing in their first legislative sessions after the Civil War. Georgia made entering private land — even unenclosed, uncultivated land — punishable by a $100 fine or a month’s imprisonment. The state also declared it illegal to enter “land, enclosed or unenclosed,” without permission. Alabama’s penalty included three months of hard labor.

But criminalizing trespassing wasn’t enough. The plantation lords understood that Black communities could still hunt and fish on public lands and waterways. So they enacted game laws specifically designed to prevent Black foraging:

In 1866, Georgia banned hunting with guns or dogs on Sundays — the only day most Black workers had free time.

Mississippi required written landowner permission for certain kinds of hunting in Black-majority counties while leaving whiter counties unrestricted.

Tennessee outlawed fishing with nets (a technique favored by Black fishermen), but only in Black-majority counties.

By 1912, Alabama’s game and fish commissioner triumphantly stated that Black residents had “become completely disarmed under the game law, and must now pursue the avocation of an honest and industrious life.”

In the legislative records, the pattern is undeniable. Counties with large Black populations got harsh foraging restrictions. White counties stayed open. The correlation is so strong that historian Charles L. Flynn Jr., author of White Land, Black Labor, called the anti-foraging laws in Georgia “legal aggression” aimed at forcing Black Americans into “dependent subordination.”

The system worked exactly as intended. Unable to feed themselves from nature’s abundance, Black Americans were forced to accept whatever wages planters offered. The closing of the southern range coincided with the establishment of sharecropping — a system that required workers to buy food at inflated prices from plantation stores, keeping them perpetually in debt. This economic stranglehold didn’t disappear with Jim Crow; it evolved.

Outside the South, anti-foraging laws were typically rooted in the classism of the early Conservation Movement — with wealthy elites restricting access to resources under the guise of “preserving” the land — and in municipal efforts to keep urban parks strictly decorative. One academic study explains that in New York State’s Adirondack region during the 1880s, for example, the push came from “elitist outsiders” who acted out of a fundamental “distrust of the inhabitants of the countryside,” namely the rural white subsistence farmers.

These residents, who relied on foraging for food and commerce, were viewed by the elites as “primitives” who practiced “slovenly husbandry” and “lack[ed] the foresight to be proper stewards of nature.” Similarly, in modern cities, parks were not designed for subsistence but for viewing and recreation, making the act of harvesting a dandelion or a berry a citable offense.

Today, the same kinds of laws that once restricted Native Americans from continuing traditional foodways, forced freed slaves into plantation labor, and imposed outsiders’ regulations on poor, rural workers now enforce artificial scarcity in modern America. While these modern laws are colorblind in text and apply to all, they maintain the historical effect of disproportionately impacting low-income communities and those whose culture traditionally relies on foraging.

Some 47.4 million people, including over 7 million children, face food insecurity. Yet cities from Philadelphia to Los Angeles ban harvesting any plants from public parks, with fines reaching $250 in New York City — more than a week’s worth of groceries for a family of four.

The stories of these laws’ enforcement are bizarre. Greg Visscher was picking raspberries in a Maryland park in 2015 when three police officers approached him for “destroying/interfering with plants to wit: berries. Without a permit.” The $50 fine was dismissed only when park officials couldn’t explain how picking a berry destroys a plant or identify the mysterious “permit” referenced in the citation. That same year, an elderly Chicago man was fined $75 for picking dandelion greens for a salad. In New York City, foraging advocate Steve “Wildman” Brill was arrested in a sting operation for the crime of eating a dandelion in Central Park. The parks commissioner said he “couldn’t stomach the idea of anyone eating our parks.”

The persistence of these laws creates tangible barriers today, particularly for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) communities. When Alexis Nikole Nelson — known on TikTok as the “Black Forager” — began sharing her knowledge, she deliberately chose that name to address this history. “I often get the question, ‘Why? Why do you need to bring race into it?’” she explains. “When I was going about making my page, I didn’t see a lot of people who looked like me in like the modern-day foraging space. To this day, here in the United States, it’s still like a very predominantly white hobby.”

Nelson, who has millions of followers and has appeared on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, started foraging out of necessity after college when she was “really broke” and “sick of eating ramen and undressed Boca Burgers every day.” She discovered that plants like curly dock growing in her neighborhood could transform simple meals into complex, exciting dishes — all for free. But she’s acutely aware that her ability to forage safely is complicated by race. In a country where BIPOC interactions with police are consistently more violent than white interactions, anti-foraging laws create disproportionate threats to communities collecting wild foods.

“My thinking, and something that will just kind of hit me in the face every once in a while while I’m foraging, is that historically, in this nation, for a long period of time, people who look like me have gathered food, picked food, processed food, not for our own benefit,” Nelson reflects. “To do this act and have often no one but myself benefiting from it, it really just feels like giving a middle finger to this system that was inherently created to put us at a disadvantage. And in that way, I do feel like foraging as a Black person is an act of rebellion.”

The good news in all of this is that people like Nelson are fighting back and winning. Indigenous-led movements are reclaiming traditional gathering rights. The Tohono O’odham Nation successfully fought for the right to gather saguaro fruit in Saguaro National Park. Seattle became the first major city to explicitly recognize the importance of foraging in public parks and now maintains a seven-acre “food forest“ where anyone can harvest. Organizations like North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems and I-Collective are working toward food sovereignty, while the Falling Fruit mapping project has documented over half a million locations worldwide where food grows free for the taking. Even some food banks are incorporating foraging expeditions to supplement donations.

As we face rising food insecurity and climate uncertainty, the abundance growing around us represents both a practical resource and a symbol of resistance. Every person who learns to identify purslane growing from sidewalk cracks, and every city that legalizes gathering fallen fruit, chips away at a system designed over 150 years ago to keep people dependent and hungry. And it can all be done through the simple act of reaching for what’s already there.

We need your help: Have you ever felt politically homeless? Voted third party? Wondered why we’re stuck with just two options? Our upcoming issue digs into how we got here. Reply with a letter to the editor.

I loved/hated learning about this. I do follow The Black Forager but did not know the history of black foraging. Thank you

This was really interesting and made me want to try and change things. Would have loved to see action items at the end of the article or a resource for organizations to support that are working to create change.