The Pentagon Papers

The leak that put truth — and the free press — on trial

In the summer of 1971, Americans woke up to front-page headlines that exposed decades of government secrecy.

The New York Times had obtained more than 7,000 pages of a classified Pentagon study formally titled “The Defense Department History of the United States Decisionmaking on Vietnam.”

You probably know it by another name: the “Pentagon Papers.”

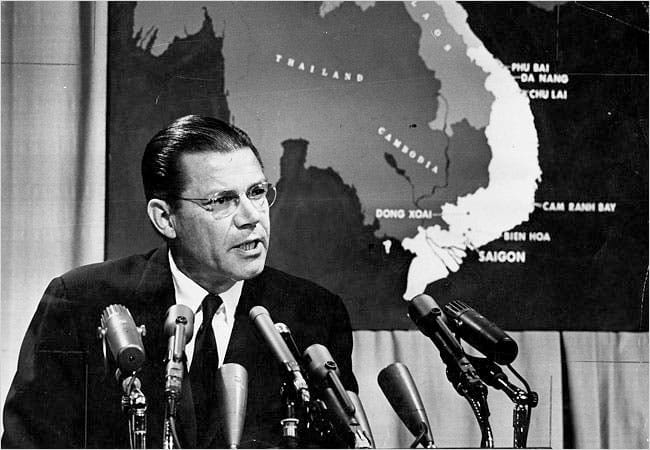

What the study contained was undeniably explosive stuff. Commissioned in 1967 by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, the classified review traced US involvement in Vietnam across five presidents — Truman through Johnson — and revealed a story the government had never dared to tell in public.

A story the government had actively lied about.

Among other revelations, the Pentagon Papers showed that senior officials knew the war was unwinnable, expanded military operations in secret, and misled Congress and the American people about why American troops continued to die in Southeast Asia.

The country was stunned. The Nixon White House, in power when the study was on page A1 of The Times, was furious. And the free press itself was put on trial.

But the story of the Pentagon Papers isn’t just about a leak.

It’s about how far ordinary people were willing to go to reveal the truth, and how their actions pushed the Supreme Court into issuing one of the strongest protections for press freedom the country has ever seen.

And the contrast hits differently when compared with the circus that is the Pentagon press corps today, with figures like Matt Gaetz and Laura Loomer posturing as “journalists” not to inform the public but to reinforce and promote the administration’s narrative to its supporters.

The Pentagon Papers were journalism. Much of what passes for “access” today is theater.

Let’s go back to where it began.

A Secret History No One Was Supposed to See

By 1967, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, the Ford Motor exec turned JFK cabinet secretary, no longer believed his own optimistic briefings. Privately, he feared Vietnam was spiraling into catastrophe. Publicly, he continued to defend the mission. Trapped between his beliefs and his perception of duty, McNamara ordered something unprecedented: a full classified autopsy of every major US political and military decision that had led America into Vietnam.

He assembled what became known as the Vietnam Study Task Force, an elite group of 36 analysts, historians, military officers, and policy experts. The group was headed by Leslie H. Gelb, then a rising star in the Defense Department as director of policy planning and analysis. (Gelb later became a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist for… wait for it… The New York Times.) The task force’s charge was breathtaking in scope: reconstruct the story of the war not as politicians told it, but as the documents themselves revealed it.

For nearly two years, the task force operated out of a secure suite in the Pentagon, sifting through an ocean of classified material — thousands of documents pulled from the Office of the Secretary of Defense, State Department telegrams, CIA assessments, Joint Chiefs memos, covert-operations files, presidential communications, and raw intelligence cables spanning five administrations, from Truman to Johnson.

They built a history no outsider had ever seen. Forty-seven bound volumes, more than 7,000 pages, meticulously cataloguing the steady, deliberate expansion of American involvement in Vietnam, often in direct contradiction of the government’s public statements.

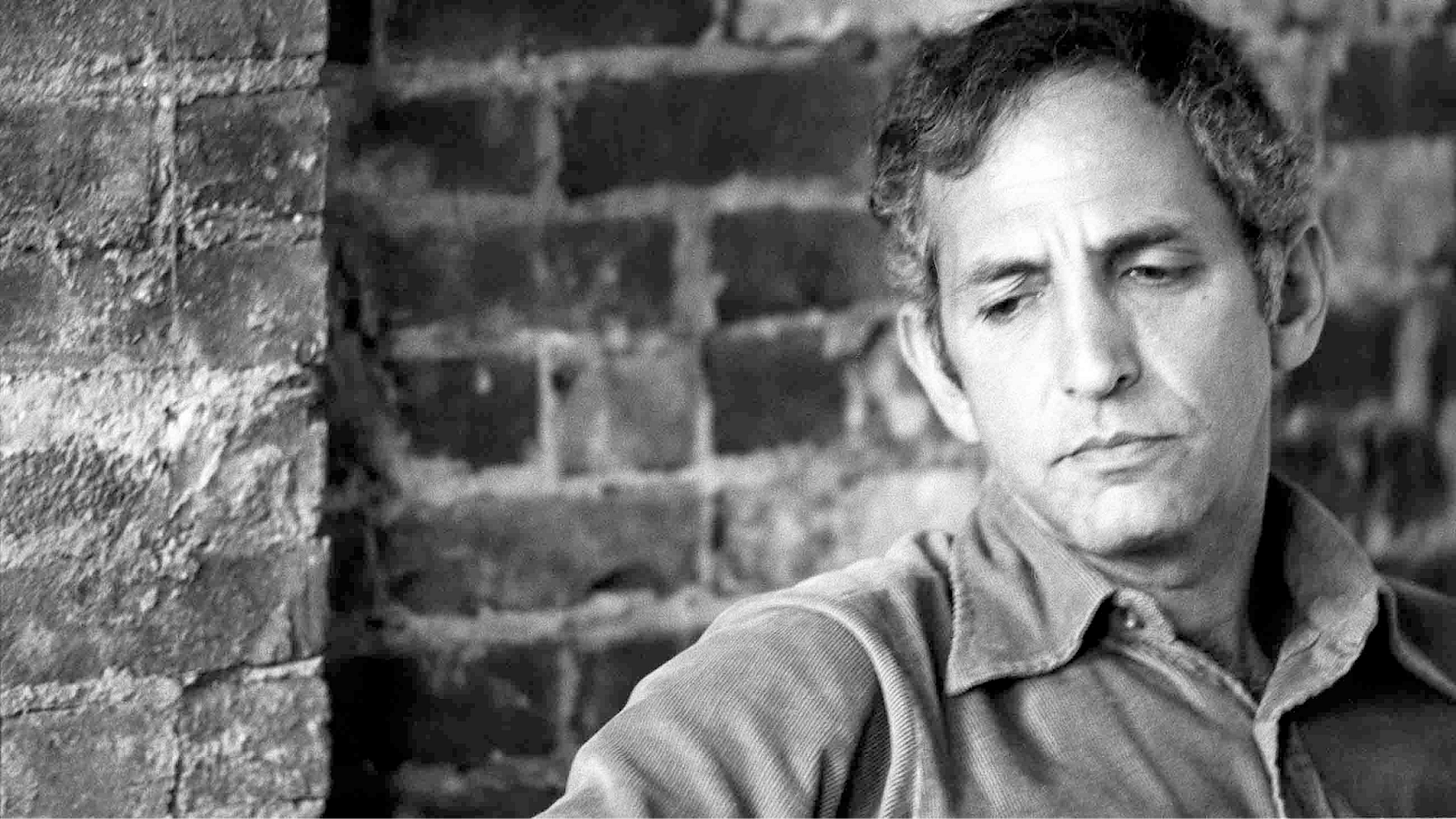

One of the analysts on the project was Daniel Ellsberg, a former Marine turned RAND Corporation strategist who had served in Vietnam and returned deeply troubled by the widening gap between government rhetoric and reality. The more Ellsberg read, the more devastating the truth became.

By 1969, he reached a moral breaking point.

The documents showed not a series of innocent misjudgments but a pattern of conscious deception; administrations that doubted the war privately but escalated it publicly; officials who misled Congress about troop levels and bombing campaigns; and intelligence assessments buried because they contradicted presidential speeches.

Ellsberg became convinced not only that the war was unwinnable but that the government knew it was unwinnable and had chosen to hide that belief from the American people.

And so he made a decision that would alter American history.

The Midnight Heist: How a Leak Was Born

Ellsberg began secretly copying the report in a homemade operation that now feels ripped from a political thriller. He snuck a few classified pages at a time out of his office under his shirt or inside his jacket, careful never to create a big enough bulge to be spotted by security.

But, even after he got the documents outside, he still needed something almost no civilian had in 1970: a photocopier. Machines were rare, bulky, and tightly controlled. Ellsberg asked a friend whether he knew anyone with access to one. By sheer luck, the friend’s girlfriend worked at a small ad agency that had a copy machine. The staff went home at night. The office was dark. That would become the first location where the Pentagon Papers were copied.

Soon, Ellsberg developed a more systematic operation at RAND — and he didn’t do it alone.

According to transcripts of Ellsberg’s interviews with Times reporters (as detailed in a 2023 investigative update from the podcast and publication Reveal), he sometimes brought his 13-year-old son and ten-year-old daughter into the RAND offices after hours to assist in the work. They acted as sentries at the hallway corner, whispering warnings if anyone approached, while Ellsberg fed “Top Secret” documents into a clattering Xerox machine that echoes through history.

And then came the closest call of all.

One night, Ellsberg’s son was copying documents while his younger sister sat on the floor cutting the words “TOP SECRET” off each page so the stack would look less suspicious. Suddenly, police officers burst into the office responding to what was later considered a false alarm. The officers looked around, saw nothing out of place, and left. Ellsberg and his children kept copying.

By early 1971, he had assembled a full illicit duplicate of the 7,000-page report and begun offering the documents to members of Congress, none of whom chose to publicize the bombsells.

Ellsberg then turned to The New York Times. Robert “Rosey” Rosenthal, then only six months into his first reporting job, was called by a Times editor and told not to come into the newsroom in the morning. Instead he was to go to room 1111 of a Hilton hotel. “Don’t tell anyone where you’re going,” Rosenthal said, “and bring enough clothes for at least a month.”

Rosey did just that. And for the next month, he and a team of fellow reporters went through the documents, verifying their authenticity and growing more and more stunned at the scope and scale of the government’s long-standing deception about what was actually happening in Vietnam.

Finally, on June 13, 1971, the first front-page story dropped.

“Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces…” — The Publication Heard Around the World

“Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement” was the headline of the story the government never intended, or wanted, the public to see.

Drawing directly from the 7,000 pages Ellsberg had smuggled out one handful at a time, The Times revealed that:

Presidents from Truman to Johnson had escalated the war even as they privately believed victory was unlikely — a throughline documented extensively in the Pentagon study.

The US had secretly expanded operations into Cambodia and Laos, years before those actions were acknowledged to Congress or the American people.

Congress had been repeatedly misled about troop levels, bombing campaigns, strategic objectives, and the scale of military commitment.

This wasn’t a policy disagreement. It was a documented pattern of systematic deception at the highest levels of government.

The public reaction was instant and seismic.

The Times’ phone lines were swamped. Members of Congress demanded hearings. Veterans wrote letters saying the revelations confirmed everything they had suspected. And inside the West Wing, the Nixon administration went into crisis mode, but not for the obvious reasons.

The Pentagon Papers did not cover the Nixon years, and Nixon and his team weren’t directly connected to the Vietnam deceit of his (largely Democratic) predecessors. Nixon believed the papers’ publication made Democrats look incompetent and untrustworthy, and yet still moved quickly to stop their publication.

Why? Nixon feared, obsessively, that his government had been infiltrated by liberal leakers set out to destroy him. And if they could leak this information, they could do the same to his administration.

Within 48 hours of the first story, the Nixon Justice Department raced into federal court seeking an emergency injunction to stop the Times from publishing any further installments of the Papers. And in a move almost without precedent in American history, a federal judge granted the request.

For the first time ever, the United States government successfully imposed a prior restraint on a newspaper — a legal order forbidding journalists to print true, newsworthy information prior to its being published.

The free press was no longer just reporting the story. It was now on trial.

And then something extraordinary happened.

While the Times was legally gagged, The Washington Post obtained its own set of the Papers. Inside The Post’s newsroom, panic met principle. Editors and lawyers warned that running the story could trigger federal prosecution. Publisher Katharine Graham, still relatively new to the job (and ironically a close personal friend of Defense Secretary McNamara), understood she could personally face criminal charges.

According to journalists reporting from the era and accounts preserved by the Miller Center, the meeting lasted hours. The room was split. But then Graham made a call that changed the history of journalism: “Let’s go. Let’s publish.”

Unbound by the injunction, The Post began to print. So did The Boston Globe. And the public kept reading while the legal battle escalated to the highest court in the land.

The Supreme Court Steps In — and Saves Press Freedom

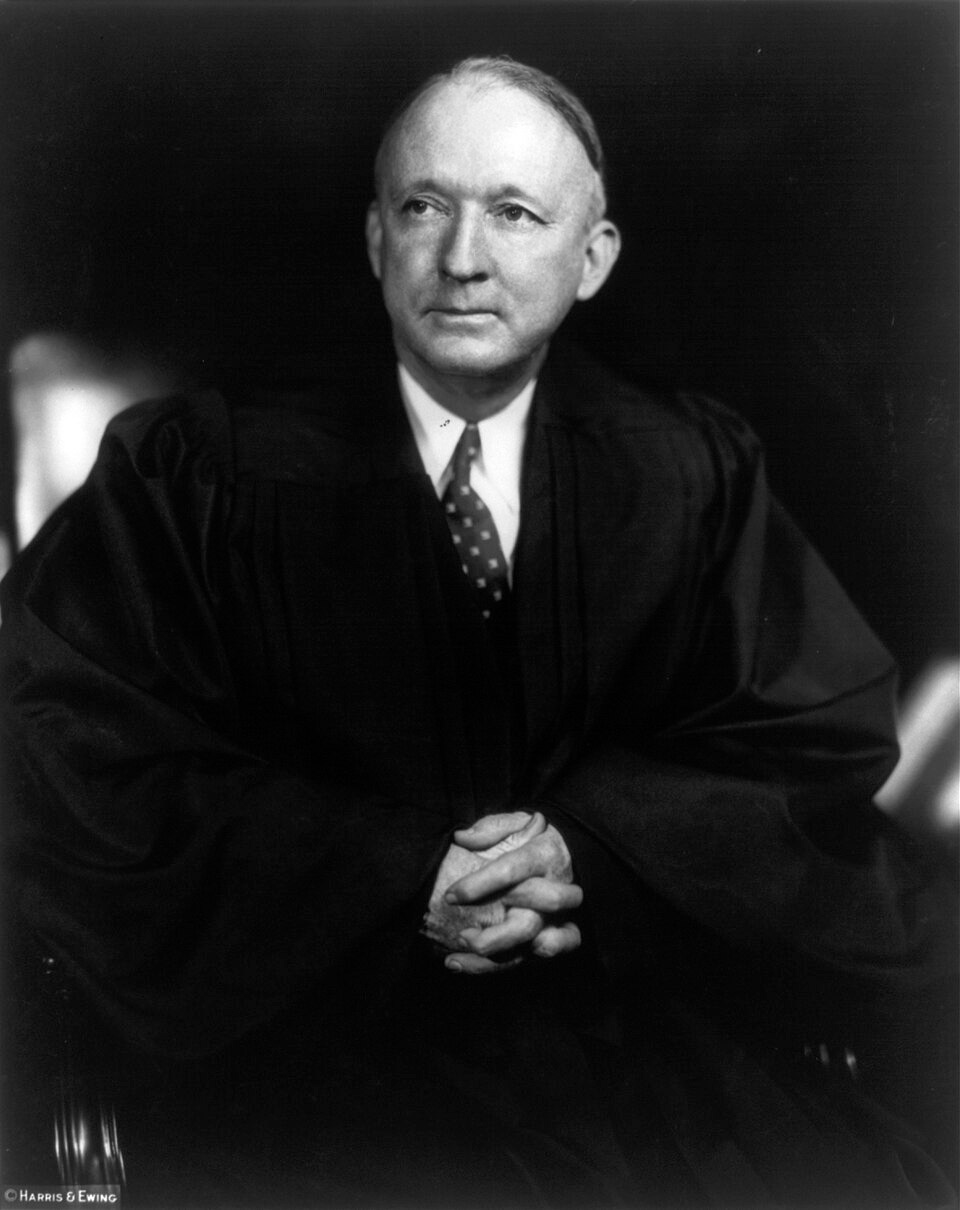

Just 15 days after the first Pentagon Papers headline ran, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case of New York Times Co. v. United States.

At issue was a constitutional question as stark as it gets: Can the US government silence the press before publication?

On June 30, 1971, in a terse 6–3 decision, the answer came back a resounding “NO.” The First Amendment does not permit such censorship.

The Court ruled that the Nixon administration had failed to meet the “heavy burden of proof” required to justify a prior restraint. Justice Hugo Black put it bluntly in his concurrence, writing that allowing the government to muzzle the free press “would make a shambles of the First Amendment.”

He continued, “In the First Amendment, the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy. The press was to serve the governed, not the governors. The Government’s power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the Government.”

With that single decision the Court reaffirmed one of the strongest protections for press freedom in American history.

It wasn’t just a win for The Times or The Post. It was a ruling that preserved the very idea of investigative journalism in a democracy.

But while the legal fight ended that day, the political fallout was only beginning.

The Nixon Administration Spirals — the Road to Watergate Begins

The Pentagon Papers triggered a paranoid collapse inside the Nixon White House. In the Oval Office, Nixon raged that the country was being sabotaged by leakers. He ordered his aides to stop leaks, telling them, “I don’t give a damn how it is done, do whatever has to be done to stop these leaks and prevent further unauthorized disclosures.”

To satisfy the president, a new and secret White House unit was established to plug leaks, a team soon referred to as “the Plumbers.” And their tactics were less than aboveboard. After learning of Ellsberg’s role as the Pentagon Paper source, the plumbers burglarized the California office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in hopes of finding incriminating and embarrassing information. (They came up empty).

After the failed Ellsberg operation, the Plumbers were folded into the Committee to Reelect the President (CREEP), where their mandate expanded to political sabotage.

The same men who broke into Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office — Howard Hunt, G. Gordon Liddy, and others — soon planned a more ambitious burglary: the nighttime break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate complex.

What began as an effort to punish a whistleblower grew into the Watergate scandal, triggering congressional investigations, televised hearings, and ultimately Nixon’s resignation in August of 1974.

What This History Means Now — Especially When “Press Access” is Government-Vetted

The Pentagon Papers didn’t end the Vietnam War. They didn’t restore trust in government.

But they did establish that the public’s right to know outweighs the government’s desire to control the narrative. And they reaffirmed the constitutional backbone journalists rely on today.

Which is why the contrast with recently unveiled rules for press access within the Department of Defense is so jarring. Among the changes, the new guidelines require that all DoD information be “approved for public release by an appropriate authorizing official before it is released, even if it is unclassified.”

Read that again.

Inside the same building where Ellsberg’s leak triggered a constitutional showdown, even unclassified information — details that have never been secret — now requires pre-approval before anyone inside the building can share it with the press or public. The rules further restrict who is allowed to speak to journalists, what counts as authorized communication, and when reporters can access subject-matter experts at all.

These are not minor procedural tweaks. They are a blueprint for controlled government-approved narratives. They also create a system where government officials can handpick which stories get told, when, and by whom, which is why “reporters” like Matt Gaetz and Laura Loomer are freely roaming the Pentagon’s press areas and asking questions of public officials while outlets like The Washington Post, the Associated Press, and Reuters are barred until they sign on to the Pentagon’s new rules.

And that is the precise opposite of what the Pentagon Papers taught the country back in 1971. A free press is only as strong as a public that can tell the difference between truth and spectacle — and insists on the difference.

Thank you for this.

It’s also worth noting the consolidation of media under billionaires is killing our free press.

Is it possible to turn on the audio feature for this post? Thank you!