The One Issue That Unites America — and Still Isn’t Fixed

Democrats blame greed. Republicans do too. Yet Americans still pay more for the same drugs.

The high cost of prescription drugs in the US has been a concern for citizens, presidents, and policy experts for decades. Unlike many issues in our politics — say, climate or guns — there is widespread agreement that this is a problem that urgently needs solving.

Perhaps stunningly, the two parties even seem to agree on some of the reasons for this problem. For example, in a recent poll, 84% of Democrats and 89% of Republicans said that “profits made by pharmaceutical companies” are a major factor contributing to the cost of prescription drugs. (I don’t know about you, but I haven’t seen this kind of coming together as a country since that fly landed on Mike Pence’s head in the 2020 vice presidential debate.)

The bipartisan agreement even extends to Congress, which is empirically much more ideologically polarized than the general American public. As recently as May of this year, Republican Senator Josh Hawley (MO) and Democratic Senator Peter Welch (VT) introduced bipartisan legislation to reduce prescription drug prices by barring pharmaceutical companies from charging Americans higher prices than the international average. President Trump has also been outspoken and active on this issue since returning to office in January.

Yet prescription drug prices in America remain stubbornly higher than those in other developed countries. A 2024 RAND report found that in 2022 (the most recent year for which comprehensive data is available), prescription drug prices were on average 2.78 times higher in the US than in more than thirty other countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (Because most OECD member states tend to be wealthy nations with high Human Development Index scores, the OECD is considered shorthand for “developed countries” in many cross-national analyses.) Trends suggest the problem is getting worse: a 2021 RAND report using 2018 data estimated prices back then to be (just!) 2.56 times higher in the US.

So what’s the issue? In order to understand why we can’t seem to crack this nut of high prices, we need to do three things. First, we need to have a little more nuance about how we got here and which drugs are more expensive than others. Second, we need to bring a systems lens and interconnected Whac-a-Mole mentality to the problem, in that addressing one aspect of the issue can risk complicating or exacerbating another. Third, as an entire country, and perhaps as a world, we need to engage in a deep ethical debate about innovating new drugs versus providing access to existing ones. Easy!

How did we get here?

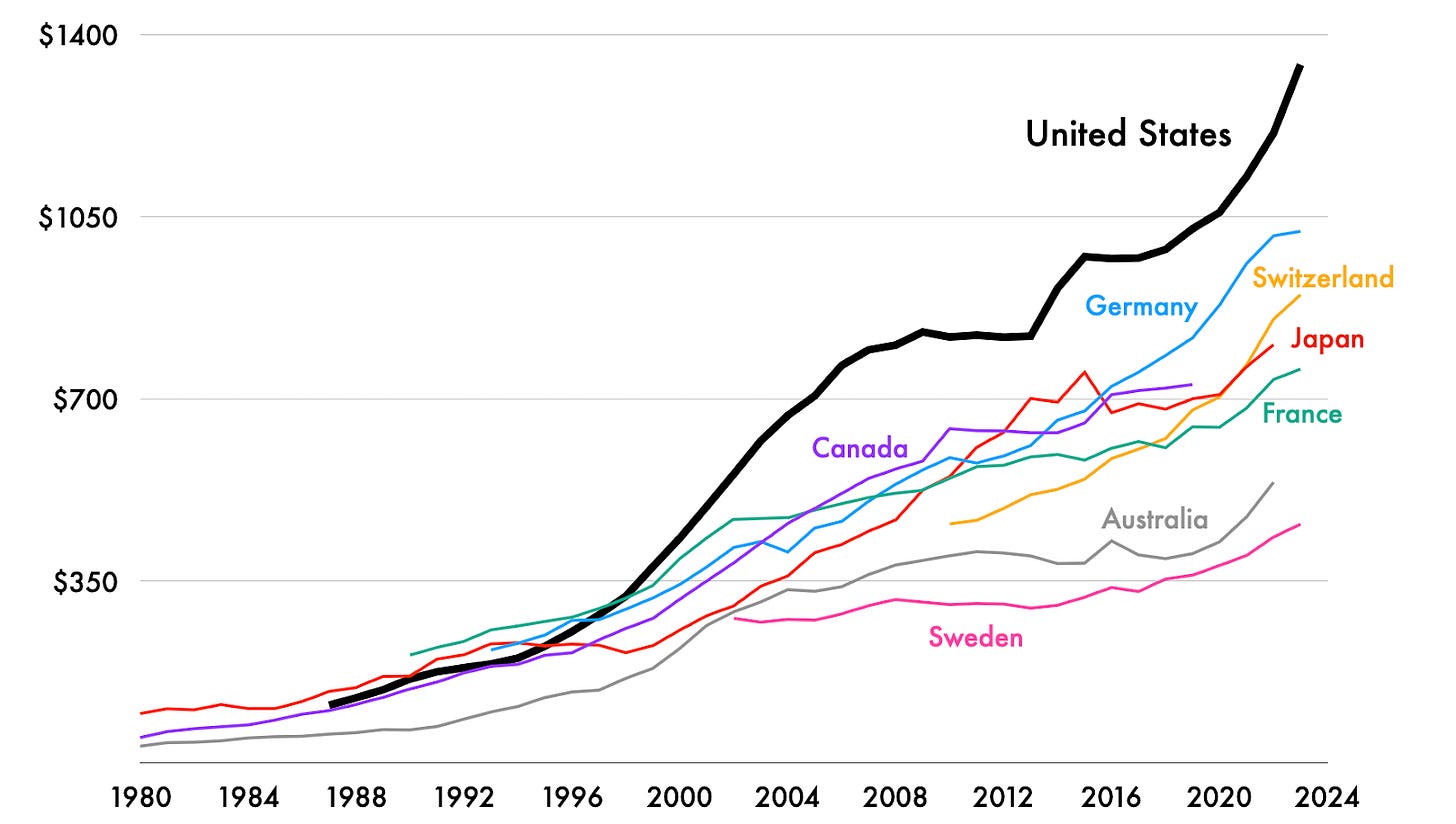

It was not always this way. The chart below shows per capita prescription drug spending trends since 1980 in the US and seven other example OECD countries since 1980. These particular seven countries were selected due to the availability of longer-term and more comparable data, but they are generally representative of trends in the non-US OECD overall. Before the mid-1990s, per person spending on prescription drugs in the US largely tracked with spending in the other countries. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, however, the prices in the US started to climb away from the group, and have mostly been on an upward trajectory since.

So what happened around that time? Two main things, according to researchers at the Commonwealth Fund: an increase in drug innovation, particularly for cancer and hypertension; and expansions in government health care, including for prescriptions, through programs like Medicaid and Medicare.

Prescription spending in the US began to diverge from other developed countries in the late 1990s

Mean per capita annual expenditures on pharmaceuticals in the US and other OECD countries from 1980 to 2024

Other research in the late Aughts observed that spending growth started to slow after 2003. They point out that this time saw an increase in drug patent expirations, greater generic drug availability, and overall reduced innovation, among other shifts. This is consistent with the notable flattening of the US price line around 2008 (and even an ever so slight decrease in 2012!) before prices took off again in 2013, at which point there was another surge in new brand-name drugs on the market, this time for hepatitis-C and cystic fibrosis, among other diseases. The passing of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 is also thought to have increased health care spending overall, though it does not alone completely explain the large, and at the time unforeseen, increase in drug prices.

This brings us to clue number two about what’s going on. While it is statistically and factually correct to say that, on average, prescription drug prices in the US are nearly three times the average amount in other developed countries, it makes it sound like every time an American goes to the pharmacy, they are shelling out three times more money than, say, their European counterparts. This is misleading. Instead, most American trips to the pharmacy come with a lower price tag than in other developed countries, but some trips are much, much more expensive, pushing up the US average.

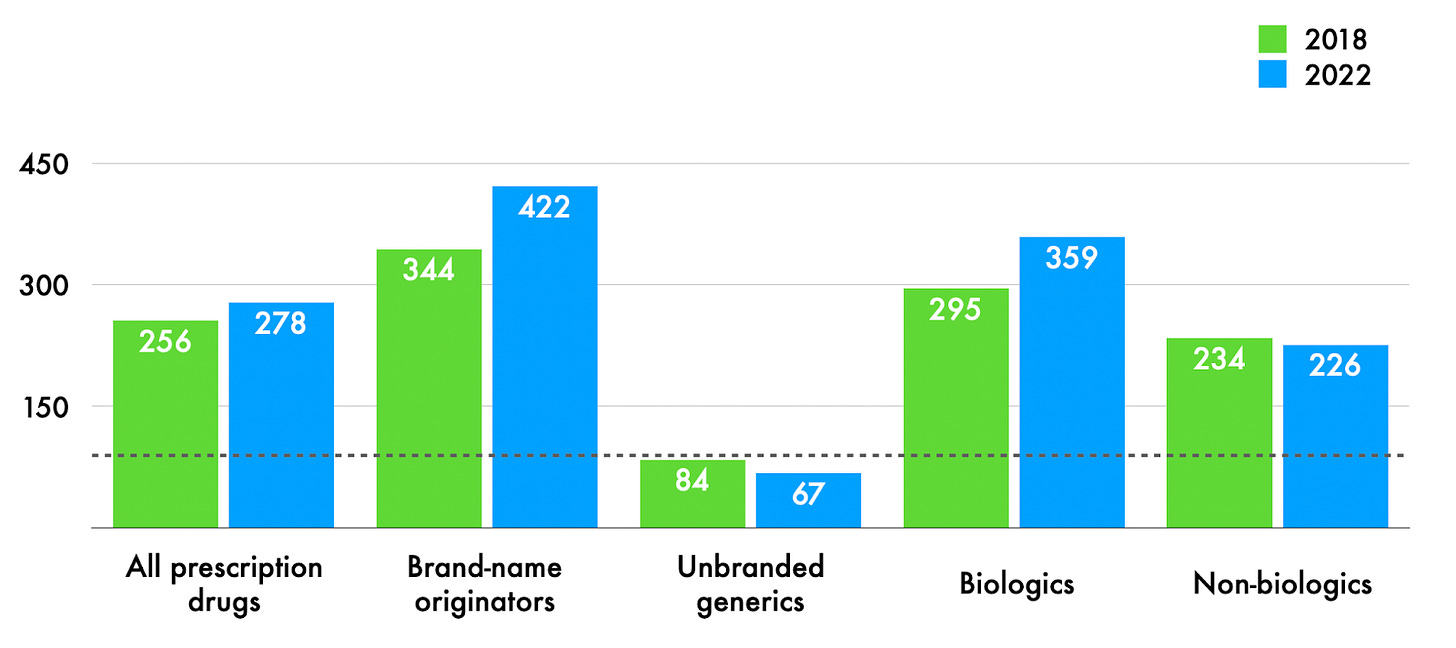

Some prescription drugs in the US are much more expensive than in other countries, while others, particularly generics, are actually cheaper

US prices as a percentage of average price in other OECD countries in 2022.

The chart above shows US prescription drug prices, separated by different types of drugs, as a percentage of prescription drug prices in other OECD countries in 2022 (the most recent year for which the breakdowns by type are available). For example, prices for brand-name originator prescription drugs in the US are on average 422% of those in other OECD countries. The horizontal dotted grey line at 100 represents parity — where drug prices in the US and other OECD countries would be the same.

Two things stand out. First, brand-name originators and a type of drugs known as biologics — which are made from living organisms as opposed to chemically synthesized like most drugs, and include blood for blood transfusions, insulin, stem cells, and monoclonal antibodies — are both far more expensive than other types. Second, unbranded generics are cheaper in the US than elsewhere. (To clarify two other terms: biosimilars are akin to generics for biologics, though the approval process is slightly different. And, yes, there is such a thing as branded generics in the US — truly anything is possible!).

Below, we can also see that prices for name-brand originators and biologics have been getting comparatively more expensive over time, while generics have continued to get comparatively cheaper.

Brand-name originals and biologics have gotten more expensive in the US relative to other countries over recent years

US prices as a percentage of prices in other OECD countries in 2018 vs. 2022.

In addition to this uneven pricing, another imbalance arises when we consider how large a proportion each type of drug is in the United States. An estimated 90% of prescriptions filled in the US are generics, while only 10% or so are the much more expensive brand-name originators. Biologics make up only about 5% of all drugs sold, yet account for more than half of prescription drug spending in the US. Biosimilars are an even tinier fraction of that, and are in fact a target of regulation reform to build out less expensive alternatives, with the EU as a promising model.

To say that only some prescription drugs are really expensive and the majority of them are cheaper than in other countries is not to deny that US prescription drug prices are a serious problem. A 2024 poll found that 55% of Americans are worried about being able to afford their families’ prescription drug costs, with the proportion even higher among Black and Hispanic respondents, as well as those without health insurance. About 28% of Americans report having difficulty affording the drugs they need, and 31% report not taking their drugs as prescribed — for example skipping doses, cutting pills in half, or using over-the-counter medication instead — due to prescription costs.

Two more caveats before we zoom in on some of the factors behind this. First, research finds Americans’ prescription drug consumption is comparable to and in some cases slightly less than that in other countries — so we can’t explain away higher prices as a result of higher demand.

Second, the prices in the data above reflect listed prices for drugs, but in the US there are cases where rebates, insurance, coupons, and loophole strategies (like buying double the dose and cutting pills in half because somehow that’s cheaper in some cases) mean that the recorded price is not the price ultimately paid by the consumer. That said, even with generous adjusting for possible discounts, the trends described above still hold. But the fact that even determining the “price” of a drug in the US is so difficult shows the kind of mind-bending analysis required to make sense of the patterns we see.

A song of incentives and fault-ascribing

So what’s going on? Brace yourselves, because experts have described this as “arguably the hardest problem in health policy today,” and The New York Times said the issue requires “complex math” to understand.

Much as in a Game of Thrones plotline, each pattern we see in the charts above is the result of interactions between multiple characters, each with their own incentives and alliances, and with messaging that tends to point the blame at someone else. Also as in Game of Thrones, it can really help to have a map:

The author’s personal artist’s rendering of the key players behind prescription drug pricing in the US

Plus a few relevant differences between the US and other OECD countries

The size of the circles for the actors above reflects my very non-scientific estimate of the proportion of blame each actor is given across public opinion polls, politician statements, industry briefs, and policy research papers. We could certainly have a robust debate about players’ exactly appropriate sizes and relationships between them, but for now we’ll keep it brief. Here’s an extremely high-level summary of the arguments for and against each player in the diagram above.

First, drug companies are typically the first actors blamed in discussions of high prices. Critics point to their abuse of patents to artificially extend their monopolies, which lets them set prices extremely high. (For example, in a “patent thicket,” one company might apply for hundreds of patents, each covering tiny if not duplicative aspects of just one drug.)

Pharmaceutical companies argue that innovation is expensive and that the prices reflect that they are taking on a great deal of risk, as the vast majority of their research doesn’t pan out. Health care researchers counter that they find no empirical association between research and development investment and ultimate drug cost. Other research points out that many of the major drug innovations in recent years that came from private drug companies were also at least partly funded by the National Institutes of Health or other public sources. Still others point out that drug companies spend large sums on advertising and lobbying, suggesting all those profits might not be going into innovation as claimed. Drug companies continue to argue that the prices simply reflect the value of their work and are what the market will bear.

What the market will bear may at least be in part influenced also by the US government, which unlike its European and other OECD counterparts does not negotiate with drug companies on behalf of patients. Countries such as France and Germany, for example, even set price caps for certain drugs, and if the drug companies won’t meet those requirements, they are not allowed to sell in their countries. Advocates for reining in prices in the US point to negotiation and price caps as obvious places for government intervention. Others say that the answer is not for the US to regulate, but rather for other countries to pay something closer to their fair share, and that the higher prices in the US at least in part reflect a market that is artificially cheaper elsewhere. Given that most drug innovation happens in the US anyway, the argument here is that Americans are unfairly footing the bill for everyone else.

Meanwhile, Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) represent a strange and uniquely American layer in the US system. These are companies that arose in the 1960s when health insurance companies started covering prescriptions. They are meant to negotiate prices between insurers, drug companies, pharmacies, and in some cases large employers, but critics argue they are monopolistic, overly complex, and incentivized to actually raise prices rather than lower them. PBMs argue that they protect customers and that drug companies are to blame.

These first three are generally considered the top players, but myriad other actors in the system have been either implicated or debated at times as well, including employers, distributors, pharmacies, doctors, and even patients. There’s also much discussion of generics. They’re cheaper, which is great for patients, but they are also susceptible to shortages, which some argue is a direct result of their prices being so low that they’re no longer worth manufacturing.

So what do we do? While the whole tangle feels like a mess of ten snakes somehow eating their own and each other’s tails, there are a few changes already afoot. Price caps set by the Biden administration for Medicare beneficiaries on ten drugs in the US go into effect in January 2026. A recent FDA relaxation of the approval process for biosimilars — allowing them to skip long human trials — could allow these less expensive versions of biologics to come to market more quickly. Repurposing drugs — when researchers, often with the help of AI, look for ways to use existing drugs to treat other diseases for which they were not originally intended — offers another route to lower costs by skipping the drug development phase altogether.

And the Trump administration is actively pressuring for change. In May 2025 the president issued an executive order demanding that drug companies charge US customers the same price they charge in Europe and other developed countries. He has announced two subsequent deals with pharmaceutical companies to pursue this policy, though he faces legal hurdles to implementation. Critics also point out a number of potential market distortions — including incentives for drug companies to charge higher prices everywhere — that may ultimately limit the impact of Trump’s order on US drug prices.

Many experts point to the need for a holistic rather than piecemeal approach.

Part of the reason all of this is so difficult is that there are so many players with so many incentives that often work at cross purposes. Another challenge is information. Not only is understanding drugs and drug pricing super complicated even under the best circumstances; the waters are further muddied by the fact that many players in the system push out articles that have headlines like “Fact check,” “Myth vs. Fact,” “Built on Myths,” and “Setting the Record Straight” but often cast blame in completely different directions. (My favorite is the last one, which argues that it’s bad for Americans to compare our drug prices to those in other countries — sorry, everyone!)

But a third and extremely difficult challenge is that we are arguing over matters of literal life and death. The trade-offs between innovation and availability, and between drugs that help a few people with a rare disease and drugs that help many people with a common one, are already hard to think about mathematically, and doing so quickly becomes impossible when you or a loved one is sick and a cure is financially unreachable, or doesn’t even exist yet because there was no financial incentive for a company to develop one. As one researcher wrote in 2020, part of the issue here might be that we’re distracted by the more news-worthy instances of price-gouging or blame-gaming and left with with less time to really think about how we are going to achieve what most of us probably want, which is to care for everyone, everywhere, all at once.

P.S. George R. R. Martin, when you finish The Winds of Winter, maybe you can help us solve this, too.

Very interesting charts on drug pricing. This is the first time I've seen that generics are cheaper in the US, and it's non-generics that are driving the average price way up for us.

"These crows ain't loyal"

Life and death, and matters that impact the quality of life for many trying to manage chronic illnesses. These tactics ensure that those that could benefit from medications do not receive them, and then go on to deal with compounding issues. High rates of amputations in populations unable to access medications for diabetes is an example of the consequences of our current system.