The Most Vulnerable Deportees

Hundreds of migrant children were almost sent home without due process

On the night of August 30, at the behest of US immigration officials, migrant children from Guatemala were awoken from their sleep at temporary shelters across southern Texas. Staff at some of the shelters — informed that the children would immediately be transported to an airport at the southern tip of the state, loaded onto a plane, and sent back to their native country — called lawyers at the South Texas Pro Bono Asylum Representation Project (ProBAR) for help.

In a court filing, one of the lawyers described what she and her colleagues saw: “At all of the shelters visited in the middle of the night, ProBAR staff witnessed children who had been pulled out of their beds. They were confused and scared. At Hands of Healing Los Fresnos, one young girl was extremely distraught, crying and repeatedly saying that she could not go back to Guatemala. At New Hope McAllen, one young girl was so scared that she vomited and asked to speak with a clinician. At Urban Strategies Alamo, one young teenager was scared that he might end up murdered like one of his family members.”

The government claimed that the children had parents waiting for them at home, but it wasn’t true: “None of these children’s parents in their home country had requested their return,” the lawyer wrote.

We don’t know specifically why each of the Guatemalan children slated to be sent back — more than 600 in total — left their home country, or how each arrived in the US. But we know the kinds of circumstances they fled and the dangers they faced on their journey.

Some sought safety from gangs or from violence at home. Some were fleeing intense poverty, which increased in many countries after Covid-19. Some lost their homes, parents, or caregivers in accidents or natural disasters. A ten-year-old girl, who “is indigenous and speaks a rare language,” suffered “abuse and neglect from other caregivers” after her mother died.

Those too young to come to the US alone might have traveled with a sibling, an older relative, or a friend. Others, less fortunate, were smuggled in by criminals who preyed on their families for money, promising to get their children to safety. Some became victims of human trafficking. The pathways vary but are consistently horrific.

As many of the children sat on planes waiting to take off in the middle of the night, a judge more than a thousand miles away in Washington, DC, held their fate in her hands. Lawyers for some of the children had filed an emergency request to block the deportations.

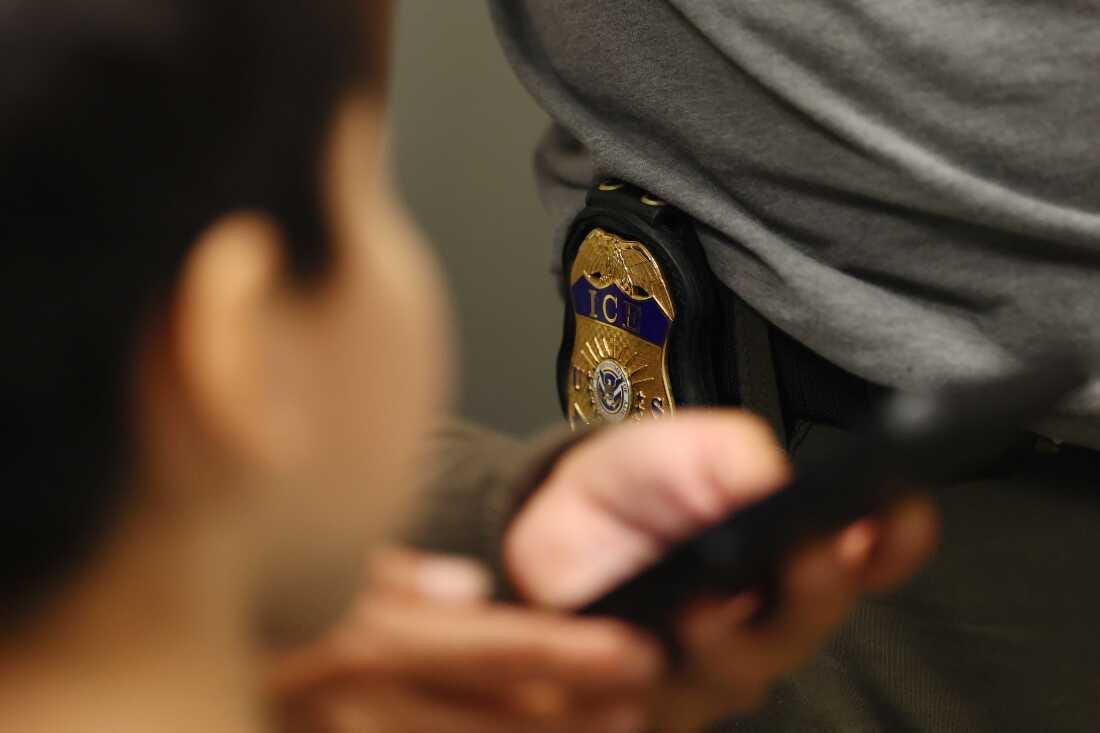

It wasn’t supposed to be happening this way. Upon arrival, minors are normally screened and processed by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to see whether they have a potential legal pathway to remain in the US. Then they are transferred to the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), which is responsible for finding foster families or local shelters to act as their sponsors.

Typically, they have the right to seek asylum, juvenile immigration status, or a visa for victims of sexual exploitation, and under US law they are entitled to a hearing and other protections specific to unaccompanied minors. But the Trump administration was trying to send them to Guatemala at night and on a holiday weekend, without notice, a hearing, or any of the other normal protections of the immigration process.

US District Judge Sparkle L. Sooknanan found the situation irregular enough that she stopped the children’s removal for 14 days as the court waited for the government’s brief about why it felt the deportations should be allowed to proceed. One of the airplanes had already taken off, but it turned around; the others were still sitting on the tarmac. The children were deplaned, loaded back into vans, and returned to their shelters — for now.

Even if they are eventually afforded a legal hearing, many of the children will have to attend without an attorney or an adult to speak for them.

In general, people who show up at immigration court with no attorney are removed from the United States at a rate twice as high as those who have counsel, and the rate is even higher for children, who likely do not understand even basic legal terms. The types of legal claims minors are entitled to make are complicated and require experienced lawyers to sort through, lawyers who understand the rules of evidence in the immigration system.

Observers from Advocates for Human Rights released a report in 2023 that offers a sense of the challenges children face in immigration court. Their report outlined situations like these:

“Given that she is three, she obviously showed no understanding of what was going on.”

“The judge explained the nature of the proceedings and the meaning of the [notice to appear in court], and asked, ‘Do you understand?’ She looked up and said, ‘no.’”

“Respondent could well be suffering from trauma or mental health issues — very withdrawn, almost inaudibly soft spoken, slumped posture often associated with abuse victims.”

Adding another layer of precarity to the process, if the child doesn’t show up at the appointed time in court, they are often ordered removed from the United States in absentia: lawyer Latin for “You weren’t here, so you automatically lose.”

For minors, appearing in court at the designated time can be challenging — they are often at the mercy of others who may not be adequately apprised of the immigration case. When they do have an attorney, however, more than 95 percent show up in court, according to data from 2005 to 2016. For unrepresented children, the figure is only about 33 percent.

As a constitutional matter, the government has no obligation to provide legal representation for these children. Immigration proceedings are civil, not criminal, and constitutional due process does not require the government to provide counsel in civil cases. A person may have a lawyer represent them in immigration court, but not at the government’s effort or expense. If they can’t afford an attorney or find one who will represent them for free, they come to court alone.

As a matter of practice, however, the United States provided some legal assistance to these children — until the Trump administration cut those programs earlier this year.

As part of the 2012 Trafficking Victims Protection Act, Congress authorized funding for nonprofit legal service organizations to provide pro bono lawyers for children in immigration court and legal education for their sponsors.

The funding was set through September 2027. In early 2025, however, the Trump administration canceled contracts with the legal service providers and pulled the federal funding. Some groups estimate that 26,000 children could be impacted.

Several of the legal service providers sued, and in late April a federal district court issued a preliminary injunction ordering the administration to continue providing the funds while the lawsuit continued. The court explained that the record “reveals substantial, immediate, and ongoing harms to the Plaintiff organizations” and that “the risk of substantial harm to unaccompanied children as a result of not receiving counsel further weighs in favor of injunctive relief.”

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld that preliminary injunction. The administration still insists it had the right to pull the funding, and the litigation is ongoing. Now some of the same questions are before Judge Sooknanan. Are the Guatemalan children entitled to both a hearing and representation? If they are entitled to representation, who will provide it while the government is arguing that it doesn’t have to pay?

Criticisms of how the United States supports migrant children are not new. The Biden White House received significant pushback for not doing more to help. In a 2023 report, “No Fair Day: The Biden Administration’s Treatment of Children in Immigration Court,” the Center for Immigration Law and Policy at UCLA explained that the failure to provide representation to children reaches back through the previous three administrations. Under Biden and Obama, there were insufficient funds and not enough government-hired legal service providers to represent every child in immigration court. But inadequate funding is different from no funding at all.

Trump has said his deportation efforts are focused on people who are “the worst of the worst.” But his administration has also pulled resources from the most at-risk group of migrants seeking refuge in the United States — traumatized children — and raced to remove them without so much as a court appearance.

For now, they appear to be safe. But if the administration has its way, they will be awakened from their slumber again one night — and this time the planes will take off, carrying them back to the perils they thought they had left behind for good.

I'm sorry but every time I hear about the cruelty we impose on children, any children (citizens or not), I can't help but think of the hypocrisy of a large chunk of the country caring so deeply for unborn children in the womb but easily looking the other way when cruelty and harm befalls real, live, breathing children every single day. I will never understand.

I felt physically ill when I first read about this. It's so cruel. Anyone who has spent any time around kids knows waking them up in the middle of the night is so disorienting for them. I'm curious if you can tell me, beyond secrecy, WHY the middle of the night? It just feels like they know what they're doing is wrong and hiding it. Is there any other reason?

Also - I'm not a legal expert, but is there some kind of volunteer system to at least accompany these kids to court? Like a guardian ad litem?