The Making of ICE

Born from the fear of 9/11, the agency built for security became a political weapon of control

In the pre-dawn stillness of September 30, 2025, helicopters hummed over a South Shore neighborhood in Chicago. Agents rappelled from rooftops, broke doors, and stormed apartments with guns drawn. In what was billed as a gang raid under “Operation Midway Blitz,” the sweep ensnared at least 37 individuals, including families and US citizen children. Eyewitnesses reported terrified residents zip-tied in their beds, hearing shouts and racialized taunts. Some children were separated from their parents. The Department of Homeland Security later confirmed that four US citizen children were taken into custody alongside undocumented family members.

Few institutions divide Americans as sharply as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the agency that executed the raid. Over the past year, ICE has intensified operations nationwide to meet a White House mandate of 3,000 arrests per day, part of President Trump’s renewed immigration crackdown. In recent months, ICE has become synonymous with raids, detention centers, and deportation flights, its agents visible in airports, workplaces, and neighborhoods across the country. From Chicago to Houston to Los Angeles, these sweeps have turned once-routine enforcement activity into front-page spectacle, with each raid feeding a volatile national debate over whom ICE is really protecting, and at what cost.

To its defenders, ICE is a vital frontline force keeping the nation secure; to its critics, a symbol of government overreach and cruelty.

Lost in the shouting, though, is any real understanding of how ICE came to be, what it was designed to do, and why it became so central to presidential power. From its hurried birth after 9/11 to its current role as a political lightning rod, ICE’s story is also the story of how modern presidents have turned immigration enforcement into an extension of their own political identity — and how a tool built for national security became a weapon in America’s political and cultural wars.

Birth of an Agency: Post-9/11 Reorganization

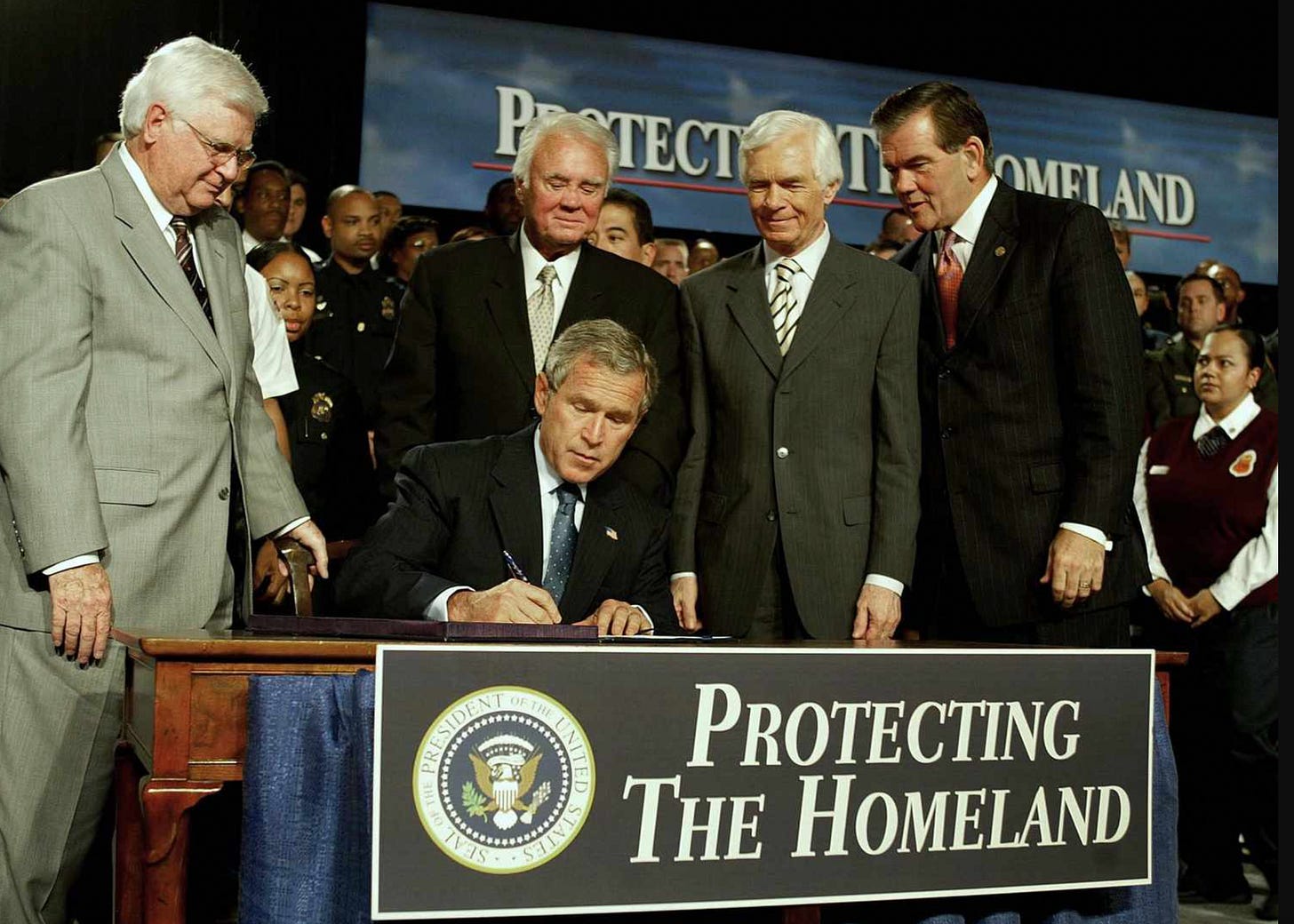

In the shadow of September 11, America’s government did what bureaucracies rarely do: it tore itself apart and started over. The nation’s leaders believed the fragmented intelligence and defense agencies that had failed to prevent the attacks needed a radical overhaul. Washington’s instinct was to consolidate disparate organizations responsible for protecting the homeland — to ensure that any future attack would not be the result of a bureaucratic blind spot. The resulting creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), via the Homeland Security Act of 2002, was the largest federal reorganization since World War II, absorbing 22 different agencies and more than 170,000 government employees.

Tom Ridge — the first DHS secretary, under President George W. Bush — framed the department’s mission plainly: to “protect the American people and our way of life from terrorism.” The agency, he said, would “have a single, clear line of authority to get the job done.” It would “bring together everyone under the same roof, working toward the same goal and pushing in the same direction.”

Among the many agencies reshuffled or newly created under DHS, one of the most consequential was ICE.

For more than half a century, immigration affairs had lived in the Department of Justice under an umbrella agency called Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). Customs enforcement, meanwhile, operated separately under the Treasury Department. After 9/11, Congress redistributed those functions into three new agencies meant to work together within the newly created Department of Homeland Security:

US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), handling visas, benefits, and naturalization;

Customs and Border Protection (CBP), charged with securing the physical border; and

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), responsible for enforcing immigration laws and investigating immigration-related crimes inside US borders.

ICE officially began its operations in late 2003, with roughly 14,000 employees, a $3.3 billion annual budget, and a clear role: be the “principal investigative component” of the Department of Homeland Security. More specifically, ICE’s charge was to dismantle criminal networks that might finance terrorism, disrupt smuggling and trafficking rings, and tighten interior enforcement (i.e., arrests and deportations) to complement border control.

For the next two decades, under presidents of both parties, the agency’s growth was slow but steady. By FY 2024, ICE boasted a budget of $11.2 billion and over 20,000 employees, its resources largely devoted to investigative work and targeted removals of violent offenders.

This transformation marks more than a budgetary expansion — it represents a redefinition of purpose, with the resources and political will to match. An agency once tasked primarily with interior investigations and targeted enforcement now operates as a vast deportation machine, driven not by changes to immigration laws debated in and passed by Congress, but by enforcement imperatives directed by the White House.

It wasn’t always so.

Political Flashpoint: From Bureaucracy to Battleground

In its first decade-plus, ICE operated quietly, largely behind the scenes of the sprawling federal bureaucracy. The average citizen rarely encountered it. Without much fanfare, it assisted local and state law enforcement with arrests and deportations and conducted transnational criminal investigations of groups that “target the American people and threaten our industries, organizations and financial systems.” But as immigration turned into one of America’s most divisive political issues, ICE’s role transformed. The agency’s work, reputation, and tactics began to shift with each administration, reflecting not just changing policy priorities but the temperaments of the presidents themselves.

In this way, ICE has become a mirror of the modern presidency — absorbing its leader’s instincts, tone, and political impulses. When a president promises compassion, ICE moves quietly; when one promises crackdowns, ICE roars. Over two decades, the agency has evolved from a low-profile enforcement bureau into an avatar of executive will.

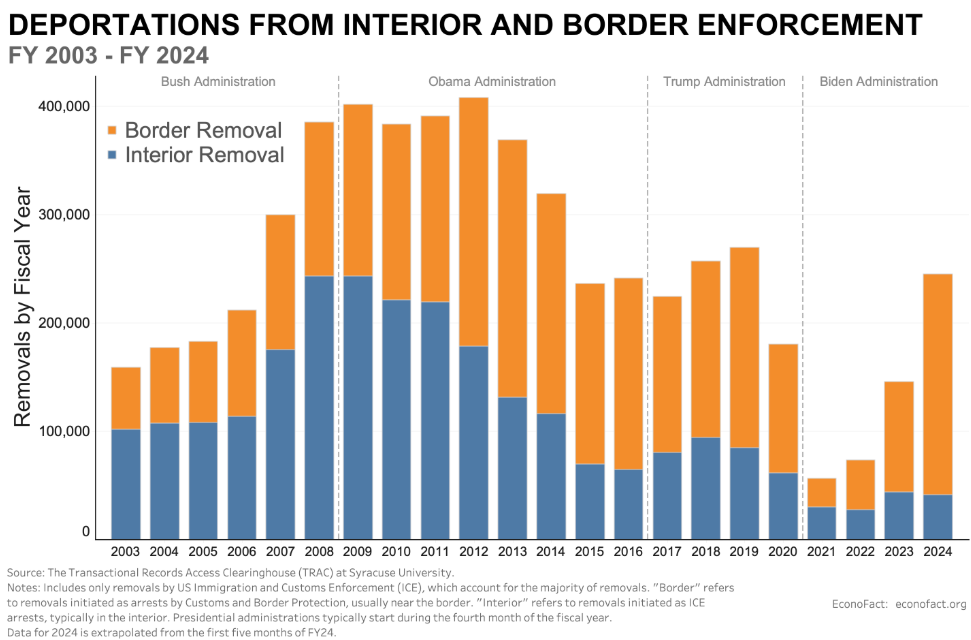

President George W. Bush’s vision of “compassionate conservatism” initially undergirded ICE’s approach to enforcement. Even as the agency was taking shape within his administration, Bush’s public emphasis was on balance — security with humanity, enforcement tempered by opportunity. In a 2006 primetime address to the nation calling for comprehensive immigration reform, Bush urged his fellow citizens to “remember that the vast majority of illegal immigrants are decent people who work hard, support their families, practice their faith, and lead responsible lives. They are a part of American life, but they are beyond the reach and protection of American law.” Despite the newly created ICE, deportations and arrests rose only modestly from the Clinton years, averaging roughly 200,000 removals annually in the early 2000s.

The real surge in deportations came from a surprising source: President Barack Obama, soon branded by critics as the “deporter in chief.” By his presidency, immigration had stopped being a technical policy debate about border staffing and visa quotas and had become a deeply polarized marker of national identity. As the electorate hardened along partisan lines, immigration became less about how many agents to hire and more about what kind of country America wanted to be.

For Republicans, toughness on immigration became a litmus test of party loyalty; for Obama, the test ran in the opposite direction. He faced pressure from conservatives to enforce the law aggressively, but his immigrant-friendly base demanded protection for those who had been brought into the country as children — a group that Obama shielded from deportation — and for long-settled families.

To bridge those worlds, Obama, like Bush, sought to prove that humane enforcement was possible — that security and empathy could coexist. Guided by the slogan “Felons, not families,” Obama focused on those with criminal records, recent arrivals, and national-security risks. By 2012, however, ICE had quietly evolved into a far more effective enforcement machine, and his administration oversaw a dramatic escalation in removals — 438,421 deportations in fiscal year 2013, the highest single-year total in US history to that point. Programs like Secure Communities and Priority Enforcement linked local law-enforcement databases to federal systems, vastly expanding ICE’s reach into nearly every jurisdiction.

The result was predictable: to immigrant-rights advocates, Obama was too punitive; to enforcement hawks, far too lenient.

In the aftermath of Obama’s uneasy middle ground, the political momentum shifted decisively to the right. An immigration crackdown had become a rallying cry for a Republican base angry over perceived lawlessness at the border. Trump harnessed that frustration with simple, visceral promises: build the wall, close the border, ban Muslims, round people up, deport, deport, deport. Where Obama had sought balance, Trump offered toughness — and in 2016, toughness won.

ICE in the Trump Era

Trump’s First Term (2017–2021)

Unsurprisingly, Trump’s 2016 campaign promises translated into aggressive executive action once he was sworn in. As a result, ICE became both symbol and spectacle. Trump’s administration instituted a policy of “zero tolerance,” in which it would prosecute all adults who had crossed the border illegally. Before, agents had prioritized violent offenders; now first-time border crossers were prosecuted criminally. In consequence, ICE separated children from their detained parents. The first Trump administration also did away with a long-standing policy of allowing asylum seekers due process to plead their case, built over 400 miles of new and replacement border barriers, and implemented sweeping travel bans on several Muslim-majority countries.

In 2019, ICE conducted more than 143,000 interior arrests, a 25% increase from the year before. The number of detainees held daily exceeded 50,000, a record at the time.

The political and cultural backlash was swift. In the summer of 2018, an “Abolish ICE” movement entered mainstream discourse amid a wave of outrage over high-profile immigration arrests in places once considered off-limits — churches, schools, even hospital maternity wards. Stories of parents detained during routine immigration check-ins, and separations of families in public view, fueled protests from Boston to Los Angeles. The movement tapped into a broader national reckoning over race, tolerance, and inclusion, with Americans debating not just the legality of ICE’s actions but what those actions said about the kinds of people who were welcome in the country.

The Biden Years (2021–2025)

When President Joe Biden took office in 2021, he pledged to do an about-face on what he called the “moral and ethical” problems of Trump’s immigration policies. His DHS curtailed interior arrests, narrowed ICE’s priorities to national security threats, and reinstated protections for children who were brought to the country as minors.

But as ICE pulled back from interior enforcement, migration at the southern border surged to historic levels. According to US Customs and Border Protection, agents recorded 2.5 million migrant encounters in FY 2023, more than in any other year on record. The figure reflected global displacement pressures, but politically it was seen as a failure of control. While Biden emphasized legal pathways and humanitarian parole programs, ICE arrests dropped to their lowest level in over a decade. The administration’s liberalizing tone — mirrored by a Democratic base increasingly supportive of undocumented immigrants — clashed with the perception of chaos at the border.

By the end of Biden’s term, the political pendulum had swung again. Public concern over border management reached its highest level since 2006, setting the stage for Trump’s return and a renewed appetite for even more aggressive enforcement.

Trump’s Second Term (2025–present)

As soon as Trump returned to the White House, he started to make good on his campaign promise to “finish the job.” His second administration has transformed ICE from a bureaucratic enforcer into the spearpoint of his governing project, and this time with the resources to do it.

The “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” passed in 2025 with zero Democratic votes, earmarked $87.5 billion for ICE in 2025 and provided nearly $29.9 billion specifically for ICE’s enforcement and deportation operations, including funds to hire 10,000 new enforcement agents. These allocations are part of what the American Immigration Council called “the largest investment in detention and deportation in U.S. history.”

Acting Director Todd Lyons compared the agency’s deportation pipeline to “[Amazon] Prime, but with human beings,” describing a logistics network built for speed and scale. The results followed: by September 2025, over two million people had been removed from or or chosen to depart the United States in less than 250 days, an unprecedented pace in modern history.

What began as a campaign promise to target the “worst of the worst, including rapists, child abusers, drug traffickers, and other violent thugs” has given way to sweeping workplace and neighborhood raids. Families, long-time residents, and individuals with no criminal records are detained en masse. More than 4,000 National Guard troops have been deployed exclusively to Democratic-led cities to assist ICE operations, an extraordinary use of military resources in civilian spaces.

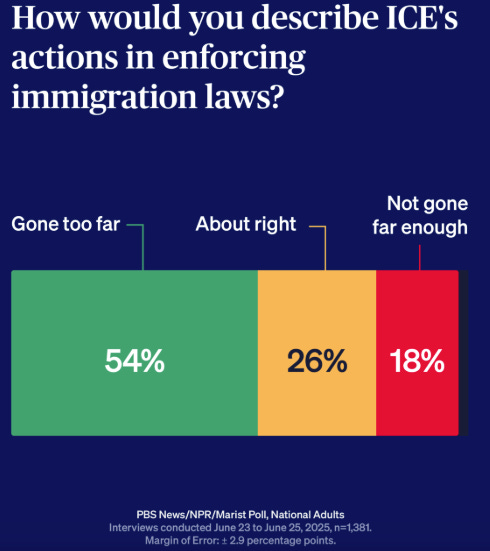

Even among Trump’s supporters, the relentlessness of these tactics sparked discomfort. Podcaster Joe Rogan, a Trump endorser, called the mass deportations of non-criminals “horrific” and “f-----g crazy.” Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA), usually one of Trump’s fiercest defenders, conceded that there “needs to be a smarter plan than just rounding up every single person and deporting them.”

The public agrees. Recent polling shows that while a large majority of Americans want to deport illegal immigrants who have committed crimes, most also think that Trump and recent ICE enforcement efforts have gone too far.

But the administration shows no signs of slowing. ICE is still tasked with meeting Trump’s public goal of one million deportations per year, a target that dwarfs any previous administration’s record. Two decades after its creation, ICE stands as proof of how emergency can become permanence: a post-9/11 reflex to prevent another terror attack has evolved into the nation’s default immigration enforcer. ICE is no longer just another agency whose place and mission most Americans would struggle to define. Its reach extends from airports to classrooms, from congressional hearings to neighborhood raids.

This iteration of ICE is far more powerful, more visible, and more controversial than at any point in its two-decade history — an agency remade in the image of its president, and a mirror of the nation itself, forever negotiating where enforcement ends and inclusion begins.

That's crazy the funding in 2 decades went from $3.3 billion to $87 billion. Can you imagine if we increased departments like the Dept of Education at the same ratio.

Thank you for that timeline/history of how ICE became what it is today. Having a relatively short history, it has totally transformed & imo, has developed into an arm of the military.