The World's Worst Humanitarian Crisis Isn't in Gaza or Ukraine

While the wars in Gaza and Ukraine are dominating headlines and campus protests, there is an even more devastating war raging in Sudan that barely registers in our collective consciousness.

The humanitarian toll is staggering. At least 150,000 people are dead, and likely many more. Nearly 13 million are displaced. Up to 80% of hospitals in conflict zones are currently non-operational. Cholera has killed 1,600 people since August 2024.

Then there is the starvation. More than 24 million are facing acute food insecurity, and over 14 million children need urgent humanitarian assistance, with 4 million suffering from acute malnutrition. Famine has been declared in the Sudanese state of North Darfur, where 635,000 people are facing conditions worse than anywhere else on earth. Many residents have resorted to eating hay or ambaz, a type of animal feed made from peanut shells. Even that is running out.

This isn't some abstract geopolitical dispute — it's the systematic destruction of an entire society, and it should horrify anyone who knows about it. One aid group says that Sudan now represents "the largest humanitarian crisis ever recorded."

Yet most Americans have never heard these statistics. Even if they can recite casualty figures from Gaza or Ukraine by heart, they struggle to remember when, or why, Sudan's conflict even began.

This raises a damning question about our priorities: Why does the world's worst humanitarian catastrophe generate so little attention while smaller crises dominate our headlines and campus protests?

The origins of Sudan’s catastrophe

Sudan has been plagued by violence for decades. A genocide began in Darfur — a region of western Sudan the size of France — in 2003, when government-backed Arab militias called the Janjaweed launched systematic attacks against non-Arab communities, killing an estimated 300,000 people and displacing 2.7 million. The violence stemmed from competition over scarce water and grazing land as drought pushed Arab nomadic herders into areas traditionally occupied by non-Arab farming communities. Rather than address legitimate grievances about political and economic marginalization, Sudan's Arab-dominated government chose to exploit ethnic divisions, arming the Janjaweed militias to crush rebellions while promoting an ideology that viewed non-Arab Africans as inferior.

The 2003 Darfur genocide gradually subsided after international pressure led to a series of peace agreements, though violence continued sporadically. Rather than disband the Janjaweed militias, the Sudanese government formalized them in 2013 as the Rapid Support Forces and placed them under the command of Hamdan Dagalo, a general known as Hemedti. The RSF’s ostensible purpose was to fight rebels, but the government was effectively legitimzing the forces responsible for genocide.

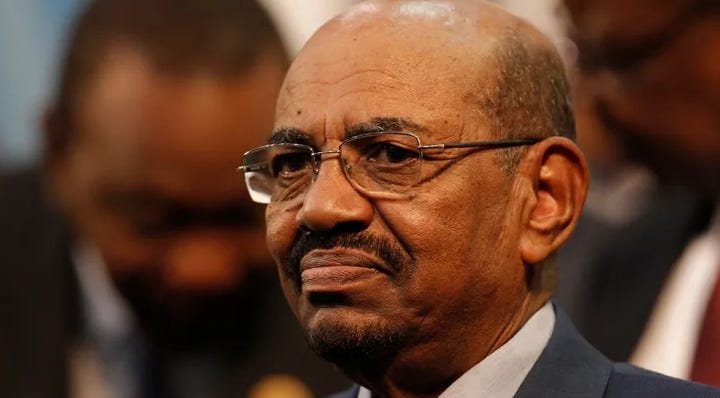

Between 2003 and 2019, Sudan remained under the increasingly isolated rule of dictator Omar al-Bashir, with the RSF expanding beyond Darfur to become a powerful national force involved in gold mining, human trafficking, and fighting in Yemen as mercenaries for Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, economic mismanagement, international sanctions, and the loss of oil revenues after South Sudan declared independence in 2011 steadily weakened Bashir's grip on power, setting the stage for a popular uprising that would bring Hemedti together with another general — Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, a leader of the Sudanese army — in an opportunistic alliance against the dictator.

Al-Burhan and Hemedti both believed Bashir's fall could lead to their prosecution: al-Burhan for the army's role in decades of atrocities, and Hemedti for the RSF's origins in the Janjaweed militias responsible for the Darfur genocide. Rather than face potential trials under civilian rule, both positioned themselves as national "saviors," hoping to control the political transition and preserve military power.

After Bashir was removed from office and imprisoned, al-Burhan and Hemedti partnered again in 2021 to overthrow a civilian transitional government meant to move Sudan toward democracy. But Hemedti coveted ultimate power for himself. On April 15, 2003, the partnership exploded when the RSF attacked army bases across the country. The fighting escalated and soon plunged Sudan into full-scale civil war.

The army’s last holdout in Darfur is the city of Al-Fashir, the capital of North Darfur. Its fall would give the RSF control over nearly all of Darfur and pave the way for what analysts say could be Sudan's division. Like the Janjaweed before it, the RSF has made the bloodshed personal and ethnic. Its fighters are committing what the US has formally declared a genocide against non-Arab communities. UN investigators have documented RSF fighters telling non-Arab women that they will force them to have "Arab babies." Non-Arab boys are shot in the streets. Non-Arab villages are systematically burned. It's a repeat of the genocide 30 years ago.

The attention deficit

Despite the huge scale of the catastrophe in Sudan, most people in the West are focused on crises elsewhere.

Gaza has a population roughly one-25th the size of Sudan’s. Yet it is Gaza, not Sudan, that dominates our social media feeds, protests, and dinner conversations. Gaza gets weekly campus occupations and Palestinian flags on apartment balconies. Sudan gets occasionally trending hashtags like "Think about Sudan" that disappear within days. Gaza receives minute-by-minute news coverage and real-time diplomatic analysis. Sudan's humanitarian collapse unfolds largely unseen.

Or compare Sudan with Ukraine. The war in Ukraine has displaced far fewer people than the fighting in Sudan has. It has not created a risk of imminent famine or involved ethnic murder on a mass scale. Yet it is Ukraine, not Sudan, that generates daily media coverage and receives billions in aid.

I'm not diminishing the tragedies in Gaza and Ukraine, or downplaying the need for aid and assistance in those places. But the disparity in attention reveals something deeply troubling about how we rank human suffering.

The World Food Programme's Leni Kinzli captured this painful reality: “There should not be a competition between crises. But unfortunately… Sudan is — I wouldn't even call it forgotten. It's ignored.”

Why the indifference?

We need to confront why 4 million refugees fleeing Sudan — equivalent to the entire population of Oklahoma — hasn't generated sustained international attention and efforts to mitigate the crisis.

Large strategic interests could partly explain the difference. Gaza captures attention because of America’s close relationship with Israel, American voters’ interest in and attachment to Israel, and America’s need to maintain stability in the oil-producing Middle East. The war in Ukraine represents a direct Russian challenge to the West, threatening European security on the doorstep of NATO.

Sudan, by comparison, does not benefit from large groups of American voters invested in its success, is remote from Western countries and alliances, and has no immediate economic implications for the West.

To be fair, the Biden administration did make diplomatic efforts to resolve the civil war in Sudan. The US co-hosted ceasefire talks with Saudi Arabia in Jeddah, appointed a special envoy, and pushed for negotiations. Biden officials imposed sanctions on both Sudanese-army and RSF leaders, formally declared the RSF's actions in West Darfur as genocide, and maintained significant funding for humanitarian aid. But these efforts faced the fundamental problem that neither warring party was committed to peace talks, and the administration never applied the kind of sustained high-level pressure that might have changed that calculation. The US also failed to hold accountable external actors fueling the conflict — particularly the United Arab Emirates, which supplies arms to the RSF.

More recent attempts by President Trump to broker peace have stalled over disagreements between Egypt and the UAE, which back opposing sides and can't agree on a framework to negotiate about the conflict. Egypt, which is concerned about the Nile River resources, supports the Sudanese army. The UAE remains a major backer of the RSF, which it hopes will counter Islamist groups. It’s also vying for Sudan’s natural resources. The US is exerting much less pressure to force the sides to come to an agreement than it is in the Israel–Gaza and Ukraine–Russia wars.

Attention begets attention

The awareness gap also reflects the way that advocacy groups’ priorities tend to be influenced by larger media and political ecosystems. The crises that dominate headlines and command viewers’ attention frequently determine the focus of aid groups and direct their emotional responses to humanitarian disasters. The result is a vicious circle in which awareness leads to greater awareness — as with Gaza and Ukraine — while ignorance of faraway suffering becomes self-fulfilling.

So why was the West more interested in Gaza and Ukraine to begin with?

In part, it’s because Gaza and Ukraine offer stark moral choices while Sudan is a study in ambiguity. Gaza fits ready-made ideological narratives about Zionism vs. colonialism, antisemitism vs. occupation, the Jewish state vs. Palestinian self-determination. In Ukraine, the West sees a nation under attack by a brutal authoritarian power as it struggles toward democracy. Sudan lacks such ideological poles — it is fundamentally a story of two brutal generals fighting for power amid long-simmering ethnic tensions — and doesn't translate as easily into campus slogans or viral social media campaigns.

In addition, scholars may find the crises in Gaza and Ukraine more interesting than the genocide in Sudan, adding to the attention disparity. Jérôme de Hemptinne, one of the world's top scholars on international humanitarian law, notes that conflicts in the “Global South” (like those in Africa) "are frequently seen as presenting fewer novel or complex legal challenges, and thus appear less compelling to scholars seeking conceptual innovation or broader public resonance."

De Hemptinne and other scholars point to the disturbing reality that victims of certain conflicts are considered more deserving of empathy than others — what they call a "hierarchy of suffering." Whether conscious or unconscious, this bias reflects "the lingering legacy of colonial hierarchies, which historically deemed the lives and hardships of certain populations as less worthy of acknowledgment." And violence in Africa is "often perceived as endemic, and thus regarded as a normalized feature of local reality."

And, not to put too fine a point on it, does the relative lack of concern about Africa's largest humanitarian crisis reflect the fact that the people at its center are Black?

The pattern isn't limited to Sudan. Ethiopia's recent conflict — between forces allied with the Ethiopian federal government and Eritrea on one side, and forces in the northern Tigray region on the other — killed 600,000 people between 2020 and 2022 but received minimal attention. A complex and bloody war in Democratic Republic of Congo has killed over 5 million people since 1998 while remaining largely absent from Western headlines.

Beyond selective empathy

This attention deficit isn't just morally bankrupt — over the longer term, it's strategically shortsighted. Sudan sits in an important location, connecting the Red Sea and Horn of Africa, which is why Russia seeks a Port Sudan naval base, its first on the continent. As the West keeps away, Putin will look for other opportunities to expand his influence.

Sudan's collapse also threatens regional stability across East Africa, with refugee flows straining neighboring countries already facing their own challenges. Chad now hosts over a million refugees, 90% of them women and children. Egypt houses 1.5 million Sudanese refugees while confronting an economic crisis. The spillover effects could eventually affect the security or economic interests of America or our allies. Humanitarian crises that fester without early engagement typically require international solutions that dwarf the expense of preventive diplomacy.

Sudan forces us to confront the ugly truth about how we consume human suffering. When 13 million people can be displaced without constant media headlines, when genocide can unfold without campus occupations, and when the "largest humanitarian crisis ever recorded" can't compete with smaller but more publicized tragedies, we've revealed the incoherence of our moral priorities.

For the 30 million Sudanese requiring humanitarian assistance, the consequences of our indifference are measured in preventable deaths and prolonged suffering. For the rest of us, Sudan represents a test of whether we truly believe all human lives have equal value — or think that some deaths simply matter more than others.

The uncomfortable answer may be that in our interconnected world, geography, race, and immediate strategic importance still determine whose suffering matters. Until we acknowledge and confront the hierarchy of suffering, our humanitarian rhetoric remains more performance than principle.

I've helped refugees from both Ethiopia and DRC obtain asylum. I'm aware of the multitude of conflicts that have caused and continue to cause incredible atrocities in Africa. I also remember when those conflicts WERE front and center - remember "We are the World" and the Suzanne Somers commercials. But we have collectively lost our give-a-sh**-unlesss-it's-me-or-mine as Americans. And I'm totally going to point fingers. We've been conditioned to worry about money more than people we don't know because it gives political power to people who benefit from division. It started with "welfare queens" (probably earlier than that, but I remember it) and has become "sh**hole countries." While Democrats are guilty of policies that don't address more global issues, Republicans are actively selling our souls for their profit.

This article, by the way, is a strange piece. Yes, we should care about Sudan for the reasons mentioned. But we should not be ascribing atrocities different values. What stands out in Gaza is that the US is playing an active role in causing the suffering and has long supported a government that has committed international crimes that have contributed to the current conflict. Ukraine stands out because if Russia wins, it won't stop. Ukraine is literally the last line of defense before WWIII. Even if Americans turn their eyes to Sudan, and they have the empathy to care anymore, what, exactly, can they do? We apparently no longer accept the huddled masses. They can send money to organizations to feed the hungry, but for many Americans, it's like screaming into the void. Other Americans will take this article to support their whataboutisms. (Also, to call the people who are against the Israel government for what they've done antisemitic is one of the tools the Republicans have used to shut up people who care about Palestinians. Don't try to legitimize that.)

I appreciate the details and updates on Sudan, yet I find it problematic to position it against Ukraine and Gaza. I worked for an international policy group in 2008 during what I would consider a media trend for Sudan. Celebrities were giving to causes and speaking about it through our organization. And Ryan Gosling wore a Save Darfur shirt for a year. Other commenters have brought up compassion fatigue and an inability to limitlessly extend attention to all issues across the globe. Beyond what the article mentions about Americans caring about Ukraine and Israel for its impact on the US, it’s also true that both of these are a nation invading another (or Gaza/Palestinians deservedly should be considered a nation), not internal crisis which has also impacted Haiti and several South American counties. Gaza and Ukraine also represent a more recent escalation that feels like we can have more influence over the outcome given the right amount of pressure (but even as they go on we’re starting to see less hope and determination in bringing them to a satisfactory end.) Whereas the situation in Sudan has gone on and on even with international intervention, money, and attention were paid to it. I do care about Sudan. I will give to organizations attempting to bring aid. I do want to see international efforts to broker peace, and I want updates with what’s happening there. At the same time, I don’t think it’s fair to call out this tragedy in comparison to Gaza or Ukraine.