The Hard Truth About Why Third Parties Don’t Stand a Chance

Inside the political, legal, and mathematical gauntlet no modern party has ever escaped.

Americans are angry with both political parties. In a recent Gallup poll, 64% of all adults reported frustration with the Republican Party and 75% with the Democratic Party. Upstart third parties have attempted to harness this frustration. And while two recent attempts to form electorally viable third parties, the No Labels Party and the Forward Party, included energetic launches and sincere appeals to political moderates, neither succeeded in even running a candidate in the 2024 presidential election.

An underlying problem behind these efforts is captured in the contradictory results of a recent Gallup poll, which found that 62% of Americans believe the country needs a third party but also reported that 59% believe voting for one is a wasted vote, helping their least favorite candidate win.

In other words, Americans are interested in third-party candidates but afraid to cast votes for them, leaving us at The Preamble wondering why these fears exist and whether they can be overcome.

In the traditional narrative that emerges from high school US history courses, third parties struggle in American politics because when they experience success — often as single-issue parties with narrow platforms — one of the two major parties plucks their ideas to make them irrelevant to would-be voters.

In this fashion, Democrats recently dealt a blow to the Green Party by co-opting its biggest idea, the Green New Deal. In 1994, Republicans made historic midterm gains, often called the “Republican Revolution,” after rolling out a “Contract with America” that bore resemblance to the emphasis on fiscal responsibility in Ross Perot’s 1992 Reform Party platform. Examples of co-optation go as far back as the so-called first modern presidential election in 1896, when Democrats ran the populist William Jennings Bryan to stifle the growth of the People’s Party, a populist group led by progressive farmers that won 22 electoral votes and 11 congressional seats in 1892.

But this narrative — in which third parties fail because their most appealing ideas are adopted by a bigger party — is incomplete. While it’s true that parties co-opt outside ideas, that’s not the whole story — nor even the most critical part — of why third parties fail.

The most formidable barrier is the winner-take-all structure of our elections. A congressional candidate might lose after a strong showing that earns 49.9% of their district’s vote, but their party will receive no representation for the performance. The same is true of Senate races. This is stifling for upstart third parties that might represent a growing share of voters but lack the name recognition and resources to win an election outright. By contrast, liberal democracies like the UK, Germany, Finland, Denmark, Switzerland, and the Netherlands use proportional representation, in which each party’s number of seats in the legislature reflects the share of the popular vote that it won, allowing parties to gain representation without winning an outright victory.

From our sponsor:

Unknown number calling? It’s not random…

The BBC caught scam call center workers on hidden cameras as they laughed at the people they were tricking.

One worker bragged about making $250k from victims. The disturbing truth?

Scammers don’t pick phone numbers at random. They buy your data from brokers.

Once your data is out there, it’s not just calls. It’s phishing, impersonation, and identity theft.

That’s why I recommend Incogni: They delete your info from the web, monitor and follow up automatically, and continue to erase data as new risks appear.

Try Incogni here and get 55% off your subscription with code PREAMBLE.

Presidential elections are also winner-take-all. Every state but Maine and Nebraska offers all of its electors, one for each congressional district, to the winner of the state’s popular vote, even if the winner holds only a one-vote advantage. As in single-member district congressional elections, the losing presidential candidate in that state might earn 49.9% of the popular vote while receiving zero electoral votes.

In short, the electoral college underrepresents strong performances from losing candidates, which is devastating for third parties trying to develop national momentum. Ross Perot, for example, won almost 19% of the popular vote in 1992 but did not receive a single electoral vote.

Hans Noel, professor of government at Georgetown, says that in this winner-take-all system, there is little incentive for voters to stray from the major parties because they know third parties will not win elections. This means that many of those interested in voting third-party ultimately don’t — leading up to election day in 2016, for example, national polling had Jill Stein at 2-4%, but only 1% ended up voting for her. This shows how it’s possible for majorities of Americans to both want a third party and believe that casting a ballot for one is a wasted vote.

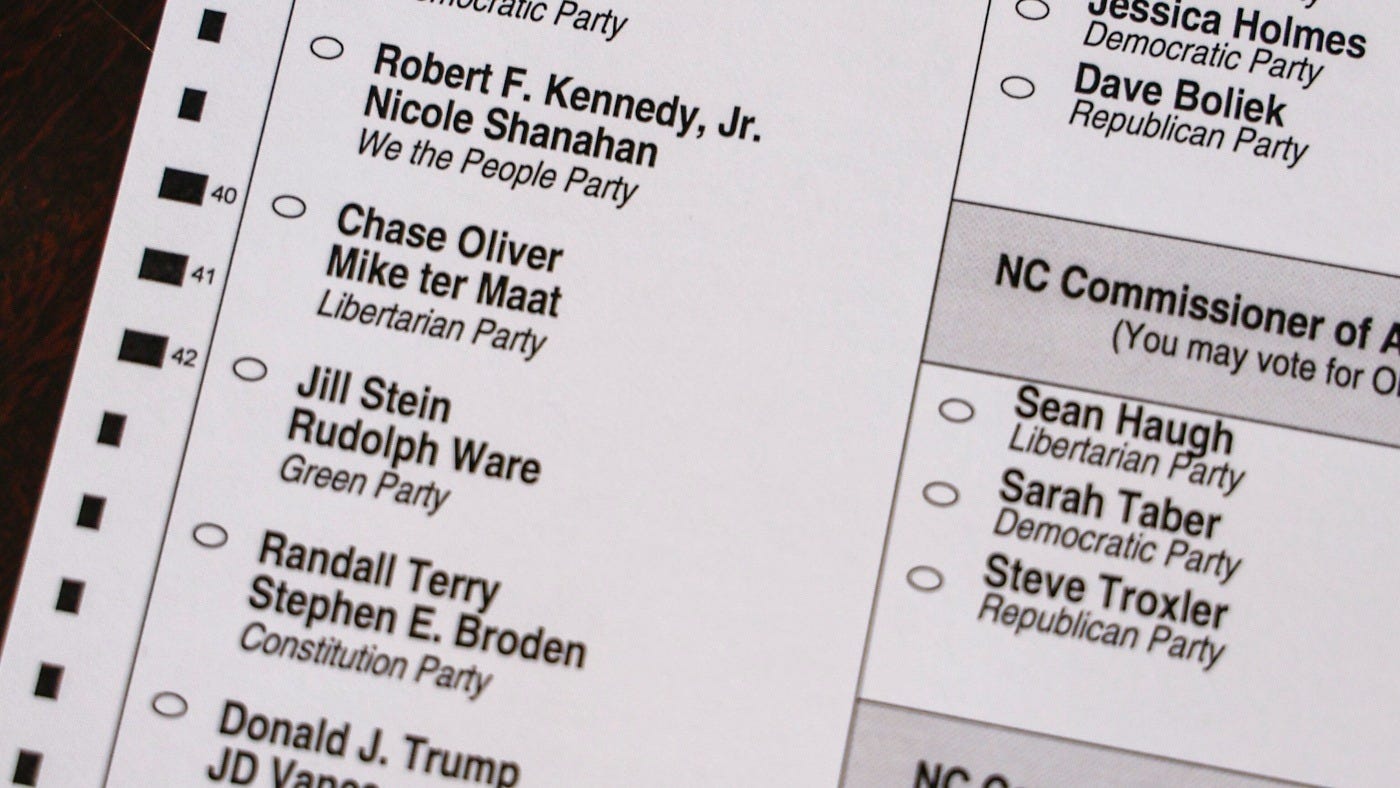

It also doesn’t help third parties that even getting on the ballot is a struggle. At the state level, where elections are administered, the dominant political parties have used their power to erect complicated legal hurdles. In California, qualifying as a party — which grants ballot access, allows the party to run candidates for positions without collecting signatures, and makes it eligible for public campaign financing — requires signatures from 75,000 people who are “willing to switch parties or register for the first time.” Texas requires 81,000 signatures in a 75-day window. In Arizona, only 34,116 signatures are required for ballot recognition, but they must be submitted one year prior to the election.

If they do make the ballot, another set of challenges kicks in for third parties. Presidential candidates need deep campaign pockets and a place on the debate stage, both of which are more challenging for third-party candidates.

In an era of billion-dollar campaigns, less established third-party candidates hold a severe disadvantage. The Supreme Court has ruled that the speech rights of corporations and special interest groups allow them to offer unlimited donations for independent political expenditures, leading to unprecedented spending via super PACs and dark money groups built around the two-party system. Third-party candidates rely instead on grassroots campaigns consisting of donations from small-dollar donors. As a result, it’s impossible for them to have media operations that rival those of their Democratic or Republican opponents.

This makes it difficult for them to get their message to voters. At the presidential level, if their message isn’t heard, they can’t garner the 15% polling numbers required by the Commission on Presidential Debates to make the debate stage. (President Trump refused to participate in the commission’s debates, leading networks to organize their own debates in which third-party candidates were also not represented.) Since 1988, only Ross Perot has qualified for presidential debates. An unsuccessful lawsuit argued that this is by design: because the commission is bipartisan rather than nonpartisan, it functions as a gatekeeper that excludes third parties.

From making the ballot to getting on the debate stage to navigating electoral disadvantages, third-party candidates face Sisyphean challenges at every stage in national elections. And if they can survive all of them, a third party will have matured into the type of formidable opponent whose key ideas will likely be co-opted by the more threatened of the two major parties.

It’s hard for third parties in America. Really, really hard.

Rank choice voting. It’s a start. Campaign finance reform. It’s absolutely crazy how much money this country spends on elections. It’s absolutely criminal in a free country? Are we truly free? Is the question🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸

Thanks Andrew! I bet a lot of people reading this will think this isn’t a huge problem because there aren’t third parties they currently support. But here’s what’s missing from that perspective: without these barriers you outline, we’d see far more candidates pursuing third party campaigns, and the major parties would be forced to compete for votes they currently take for granted. It’s like monopolistic practices in any market. When competition is artificially restricted, it’s hard to see what you’re missing out on. Like it’s hard to envision what Google might have had to become if other search engines had access to being the default on my iPhone’s browser and they needed to get more innovative to earn my business. Maybe there would be something much better for web searches, it’s impossible to know. In the same way, it’s hard to see what hard choices the major parties are avoiding because they face no real threat to their existence through irrelevance.

Let me illustrate with something I witnessed firsthand. I volunteered for the brand new Harris campaign in October 2024, expecting a staff thrilled to see volunteers ready to hop on a bus and knock on doors in a last ditch effort to prevent a second Trump term. That wasn’t the vibe at all. The staff had just converted from the Biden campaign, and they couldn’t even muster fake enthusiasm. They were openly resentful that Biden had been forced out. They quibbled over petty things that seemed absurdly unimportant given what was at stake.

This isn’t the fault of individuals; they are just responding to a poorly designed system. People who work for the Democratic or Republican party aren’t worried about whether they’ll have a job based on election results. Win in a landslide or suffer a humiliating defeat, the machine keeps running. The main job every cycle, regardless of outcomes, is raising money to spend on advertisements that harass swing voters with apocalyptic warnings about the other guy. There’s no accountability, no real competition forcing them to earn their positions.

A better, more democratic system would involve ranked choice voting. This wouldn’t just make third party candidates viable. It would force all candidates to campaign on positive visions rather than fear-mongering. It would make campaign staff actually work to keep their jobs. The major parties would stop operating like comfortable monopolies, resting on their laurels and resenting anyone who demands they actually earn votes through action rather than fear.

Sorry for the shameless plug again, but I’m gathering people who want to make constitutional reforms a major campaign issue for the 2026 midterms. This week I’m writing about campaign finance reform and Citizens United, but ranked choice voting will get its turn. This week’s post tells a personal story about what’s wrong with our current system of political fundraising: I attended a lovely local political event and signed up for their email list so that I could attend more. The person who signed up right after me was named Sara, but due to a data entry error, event organizers attached her name to my email address. This turned out to be an accidental tracking system. Every time I received an email addressed to “Sara” at my email address, I knew exactly where it came from: the organizers of that one local event had sold my data. First came emails from national campaigns across the country, then ads for non-stick pans and air filters, then scammy job offers, then phishing scams about loan applications and free money. Apparently now I need that Incogni service you mentioned in the article. Why should getting involved in local politics mean having your data harvested and sold to scammers? Because money, money, money. The system is designed to extract, not to serve. Looking forward to sharing the full story!