The Funding Fiasco

White House thinks budget bills should be more partisan

Today's issue is sponsored by the Pew-Knight Initiative

When Democrats win national elections, they often promise to rein in defense spending and expand domestic programs.

When Republicans sweep into power, they often pledge the reverse: a bigger Pentagon budget, a smaller social safety net.

But can I let you in on a secret?

No matter who’s elected president, the breakdown of the federal budget remains approximately the same.

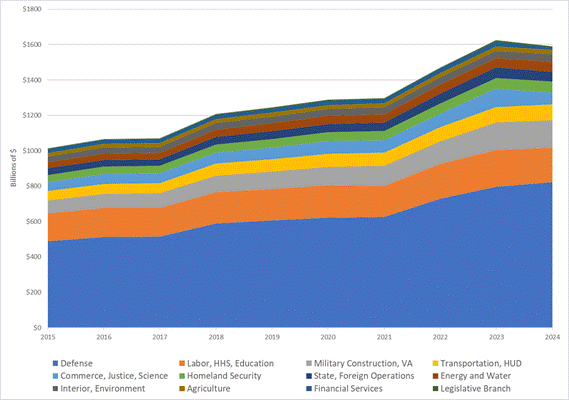

Here’s a graph from the Congressional Research Service that shows how much money was put towards each category of the budget every year for the last decade.

This chart isn’t adjusted for inflation, so you see everything going up and to the right — but the point here is that everything is going in that direction, basically in tandem. There isn’t much variation as we march from Obama to Trump to Biden.

Defense, education, the environment, you name it: every category maintains about the same proportion of the federal budget from year to year. During Covid, there was a big spike in the overall size of the budget. But instead of some programs growing and some shrinking, they all just grew together.

This pattern of stability, despite all the change and chaos in Washington, might seem surprising. But the Senate filibuster can help explain it.

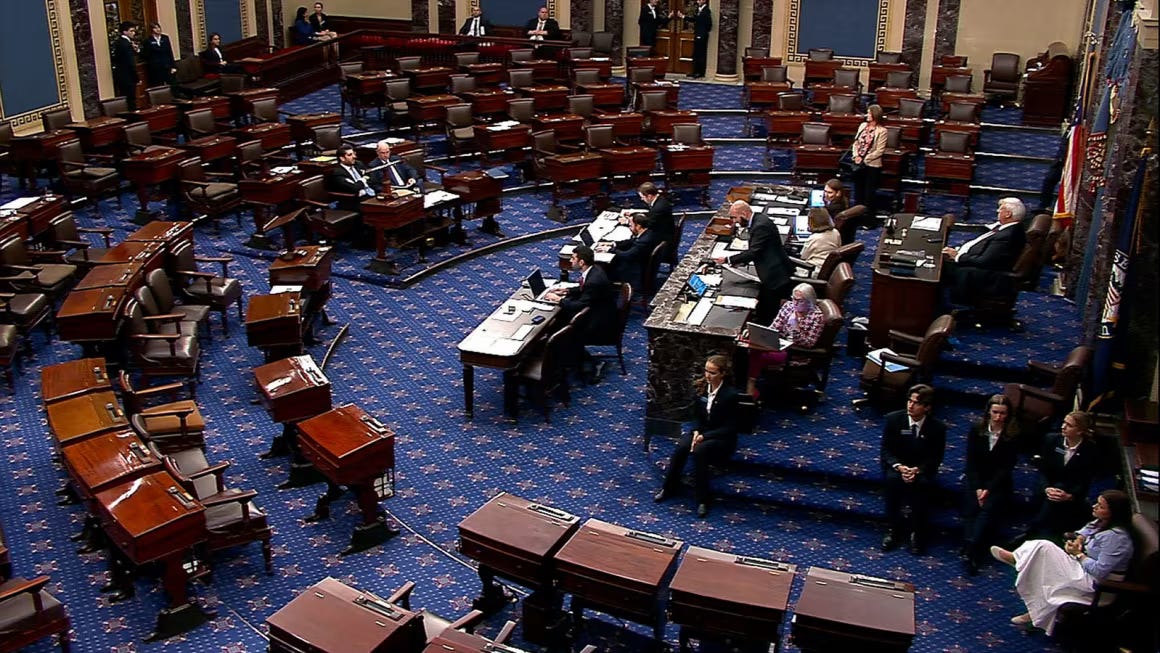

In the Senate, most bills need support from 60 out of 100 senators in order to advance. (Bills that fail to meet this threshold are said to have been “filibustered.”) This requirement extends to appropriations bills, which are the pieces of legislation Congress uses to set government funding levels each year.

It’s rare nowadays for either party to control 60 Senate seats, so that means Congress generally has two options:

Strike a bipartisan funding deal.

Shut the government down.

Occasionally, lawmakers will choose Door #2 for a few days or weeks, but generally, they take Door #1. This is why each arm of the government ends up controlling about the same slice of the budget pie from year to year.

No matter which party is in the White House or even which party controls a congressional majority, to advance a funding bill in the Senate, bipartisan agreement is required — which means Republicans struggle to cut domestic spending and Democrats have a hard time slashing defense. At most, all that changes is that both categories grow, both to account for inflation and to allow each side to please constituencies within their party.

Usually, the only way for Democrats to get non-defense spending up is to trade off an increase in defense spending (and vice versa for Republicans). Both parties accept this status quo, as they’d rather increase parts of the budget they dislike than risk shrinking parts of the budget they do like.

Each year, Congress passes these bipartisan bills (usually tied together in one big appropriations package, much longer than anyone can read), and the president signs them. Then he sees to it that the executive branch carries out the agreed-upon spending. This compromise doesn’t make everyone happy, but it keeps most people happy enough. Sure, the trough keeps getting bigger (which will have consequences for taxpayers down the line), but at least this way both parties can ensure that their allied interests keep getting fed.

But now, Donald Trump has chosen Door #3: making an end-run around Congress and trying to make government funding decisions along party lines.

In his six months since returning to office, Trump has repeatedly undermined the bipartisan appropriations process, the foundation of how the government manages to stay open year to year. A fight over these efforts is poised to come to a head in the next few weeks, potentially sparking a government shutdown.

Trump has gone about this in three phases.

Phase 1: DOGE

In Trump’s first days and weeks in office, the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) went about canceling numerous government contracts and grants, including in ways that federal judges later ruled contradicted the appropriations bills approved by Congress.

“The appropriation of the government’s resources is reserved for Congress, not the Executive Branch,” one judge wrote in an order blocking a freeze of federal grants that the Trump administration had attempted.

In another case, a judge wrote that the administration had “terminated programs established through lawfully enacted congressional appropriations without any basis in statutory authority.”

DOGE’s influence has significantly declined since Elon Musk’s departure from the White House, but the attempts to cancel government programs — even without permission from Congress — have continued. The Government Accountability Office (GAO), a nonpartisan agency that acts as the government’s in-house auditor, has twice said that the Trump administration has held back congressionally approved funds in violation of the law. It is investigating dozens of additional alleged violations.

Phase 2: Reconciliation

After defunding programs he didn’t like, Trump went about funding the programs that he did.

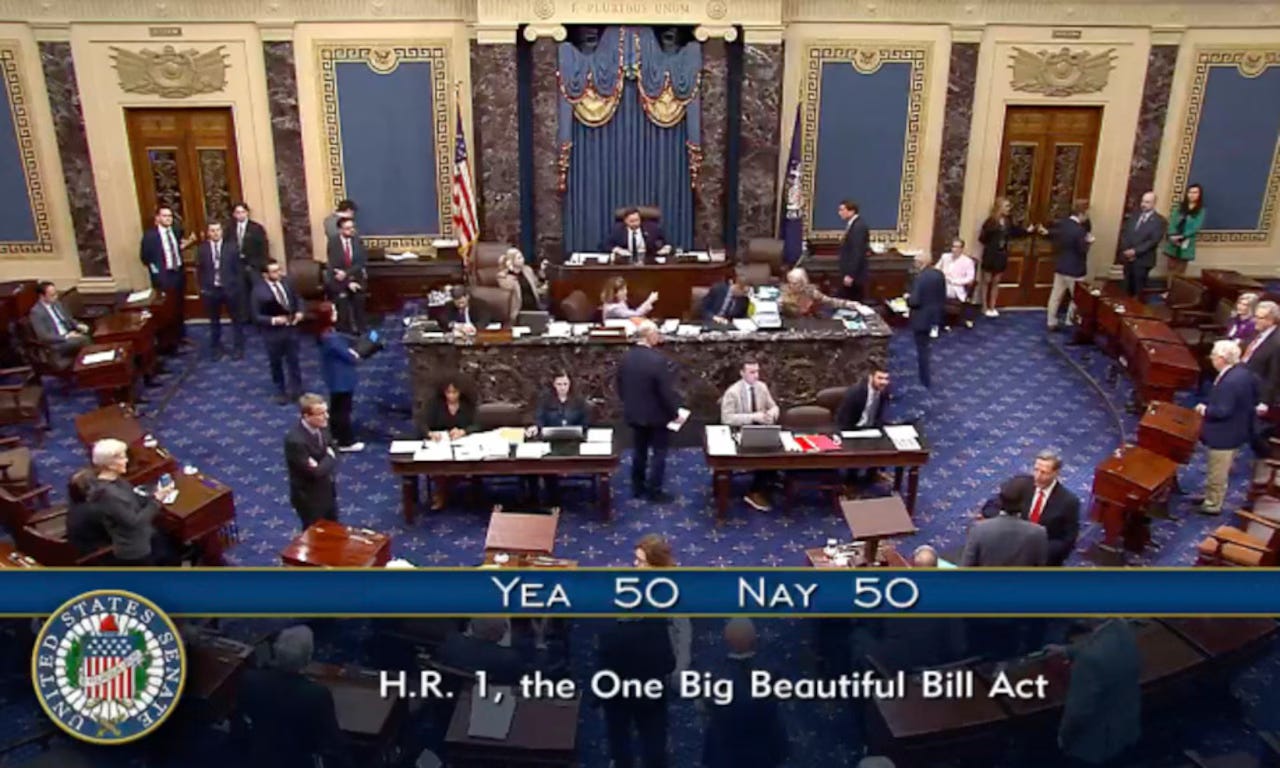

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, signed into law earlier this month, included $150 billion in increased defense spending and $140 billion in new border security spending, as well as cuts to Medicaid and food stamps.

The package was passed using the reconciliation process, which — unlike the normal appropriations process — requires only a simple majority to advance in the Senate. That way, Republicans were able to add money for the Pentagon without needing to cede anything to Democrats.

Phase 3: Rescissions

Then it was back to defunding. Last week, lawmakers sent a package to the president’s desk clawing back $9 billion in government funds, including money that was set to go to global health programs, refugee assistance, and international peacekeeping, as well as the entire 2026 and 2027 budgets for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.This measure used the rescissions process, another legislative work-around. Under this process, the president can request that Congress allow him not to spend certain funds that they previously approved as part of the appropriations process. If both chambers of Congress approve the rescission request within 45 days, the funds no longer have to be spent.

Importantly, rescissions bills — like reconciliation measures — are not subject to the Senate filibuster.

From Pew Research Center:

Who decides what news is? The power to define news has largely shifted from media gatekeepers to you, the general public.

A study from Pew Research Center’s Pew-Knight Initiative explores the changing dynamics of news consumption. Find out how identity, facts, power and social value shape how Americans think about “news.”

Do your feelings align with the public? Check out the report here.

Legally and politically speaking, these phases are all different.

Reconciliation has become a fixture of Washington policymaking, so it’s not new for lawmakers to approve some amount of new funds along party lines when they claim power.

Rescissions, too, are perfectly legal — but they haven’t been used for most of the 21st century, sort of like a sleeping giant that Trump has now awoken. The types of cuts DOGE attempted to make unilaterally, meanwhile, have no obvious precedent in recent political history. (Ironically, the same law that greenlights rescissions, the Impoundment Control Act of 1974, also provides the best basis on which to argue that the DOGE cuts are illegal.)

It’s the combination of all three phases, especially the renewed practice of spending cuts via rescissions and the novel practice of spending cuts by presidential fiat, that threatens to forever change how Washington writes its budgets.

Imagine, for a moment, that you’re a Democratic lawmaker. The government’s current funding is set to expire on September 30, at the end of the fiscal year. Without Democratic support, new appropriations bills (or a continuing resolution that extends them) won’t be able to pass due to the filibuster.

But why would you help a bipartisan spending deal reach the 60-vote threshold if you knew that Republicans could then use a rescissions bill to claw back any concessions they made to you with only 51 votes? Or if President Trump might just decide not to spend the funds himself?

How can spending negotiations proceed with those possibilities hanging in the air?

That’s the question many Democrats are asking right now. They’ve yet to unite behind an answer, partially because a government shutdown — which would occur if they refused to bless the appropriations bills — could empower Trump in its own ways. (That’s why Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer declined to trigger one the last time this question came up, though the decision wasn’t popular within his party.)

Divisions among Democrats are already cropping up once again as they mull over how to address this problem.

The Senate voted 90–8 to advance a bill funding military construction and veterans programs on Tuesday, a positive sign for the appropriations process. But Schumer has yet to commit to supporting the measure for final passage, noting the vulnerability of the talks. “Given Republicans’ recent actions undermining bipartisan appropriations, nothing is guaranteed,” he said.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), one of the eight dissenters, has signaled plans to oppose appropriations bills unless the GOP pledges not to pass another rescissions bill, as the party is gearing up to do. .

“I don’t understand what it means to negotiate an appropriations deal with Republicans, unless they put in writing that there will be no rescission and no impoundment,” Sen. Warren has told reporters. (“Impoundment” is a legal term for presidents’ declining to spend funds without permission from Congress.)

At the White House, the man at the center of all three of these interlocking efforts is Russell Vought, the president’s budget director, who has advocated a vision of “radical constitutionalism.” In addition to helping shepherd the reconciliation package through Congress, Vought has been intimately involved in the rescissions bill and the president’s attempts to withhold additional funds.

As he stares ahead towards a September spending fight, Vought is saying the quiet part out loud.

“The appropriations process has to be less bipartisan,” he said last week. “It’s not going to keep me up at night, and I think will lead to better results, by having the appropriations process be a little bit partisan.”

But, as long as the Senate filibuster remains, the appropriations process needs to be bipartisan — unless Washington accepts a new normal of adding spending by reconciliation and cutting it by rescissions, without buy-in across the aisle.

“Mr. Vought’s lack of respect and apparent lack of understanding of how Congress operates is baffling, because he’s served in government before,” Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) told NBC News.

Other Republicans seemed less bothered. “We don’t have an appropriations process. It’s broken. It’s been broken for a while,” Sen. John Kennedy (R-LA) said, predicting that Congress will rely on continuing resolutions and rescissions packages for the rest of Trump’s presidency.

But even continuing resolutions require bipartisan support. If Democrats refuse to vote for one (which they might do as long as Republicans refuse to rule out future rescissions), we might be headed towards a government shutdown before long.

Luckily, Congress has plenty of time before the September 30 deadline. Oh, wait: they’re taking all of next month off? And the rest of this week too? This could be a problem.

I vehemently disagree with Vought here. We do not need more partisanship in the US.

Thank you, Gabe! I learned a lot from this.

My main question after reading this is: where have the conservatives gone? Looking at that chart you shared, there doesn’t appear to be such a concept as fiscal conservatism anymore, just different flavors of spending. Elon Musk was apparently bamboozled into thinking he was part of a conservative administration but has stormed off to form his own party where the government is more fiscally conservative — except, of course, where his personal financial interests would be in conflict. The whole DOGE experiment was less about genuine government efficiency and more about political theater that even the courts saw through.

This makes me think about future generations, which is funny because I don’t think I’ll ever have kids, but I look around at these politicians and voters and think… I thought y’all love kids, right? Would you buy a new car with your kids’ college fund? Because we are setting our kids and grandkids up to be paying interest for things like ICE expansion and Alligator Alcatraz for the rest of their lives. Every dollar spent on these partisan priorities through reconciliation and rescissions is a dollar that future taxpayers (your kids and especially your grandkids!!!) will have to service with interest.

At least when Democrats are spending our kids’ money, they’re investing in kids’ future with free school lunches, healthcare, and infrastructure. Republicans are flushing it down the toilet on industries of harassment and destruction. The $140 billion in new border security spending you mentioned isn’t building anything that will generate economic returns or improve lives — it’s just expanding a punitive apparatus that will require endless feeding.

Another example of this reckless budget logic is how we’re gutting Medicaid. By not funding healthcare for these recipients, rural hospitals will fail. But then Republicans, if they are going to do anything about it, will just throw money at keeping those hospitals’ lights on without actually helping patients — so we keep spending but save fewer lives. That’s the opposite of conservative.

Is there not an appetite for a political message that goes along the lines of “stop spending our grandkids into a debt spiral”? Because what you’ve described isn’t just a process problem — it’s a generational theft problem with no conversation about how to stop. When Russell Vought says he wants appropriations to be “a little bit partisan,” he’s essentially saying he wants to be able to raid the future without having to justify it to anyone who might object. It’s just reckless spending with a red hat on.