The Faith That Powered Freedom

From Frederick Douglass to Martin Luther King Jr., why Christian belief supplied America’s most persuasive vocabulary for justice.

As a Black Christian and racial justice advocate, I’m not naive to the fact that many proponents of racial equality view Christianity as a hindrance to justice — but I have a very different perspective. As I see it, Christian teaching has historically been the most powerful engine in advancing racial justice in the US. It’s hard to fathom how the most significant strides in our history could ever have been made apart from Christianity.

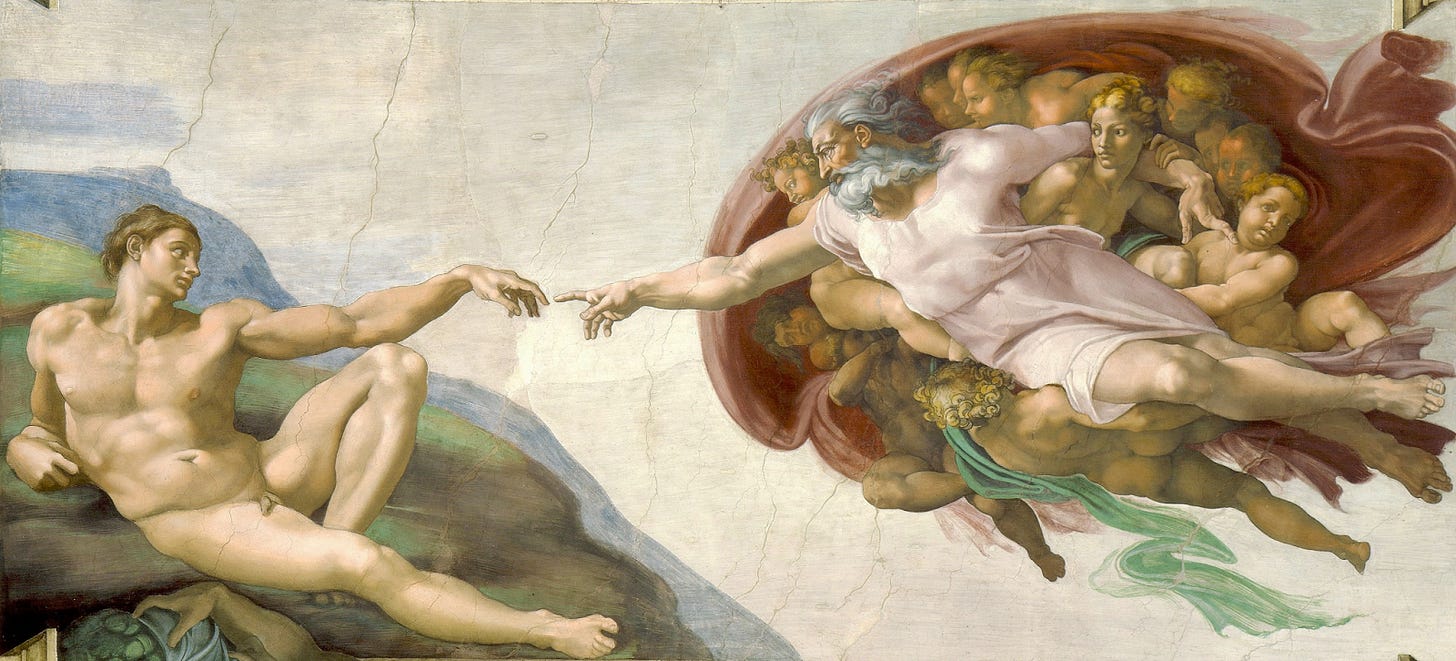

The most effective racial justice advocates in US history appealed to the shared moral vocabulary that the Christian faith provided. Christian belief was crucial to the case for abolishing slavery and ending segregation, and is even the reason that our Constitution claims “all men are created equal.” The hope for equality has come to be seen as a universal good in America today, but we inherited this belief from advocates who were making a distinctly Christian claim: that every person is of great worth and equal value. In the Christian tradition, it’s believed that the value of all people is inherent (automatically given to all by God) and immutable (can’t be reduced or changed). That is why the Christian faith is fully compatible with — and has actually been essential to — the fight for racial equality.

Understanding how racial justice fits into the Christian faith is personal for me. I’ve come to believe the fantastical claim that the God who created all things entered the world in the person of Jesus. I regard the story of Scripture as the one “true myth,” as J. R. R. Tolkien was known to say. I’ve studied the Bible for years. I’ve even taken a few semesters of seminary just for the heck of it. And as a Black person devoted to racial equality, I’ve found questions of race and justice caught up in my path every step of the way.

I hope to share what I’ve learned along the journey and show that: (1) Christianity has been essential to racial progress in the US. (2) Racial injustice is thoroughly un-Christian. (3) The Christian view of reality provides the best basis for justice and morality.

1. Christianity has been essential to racial progress in the US.

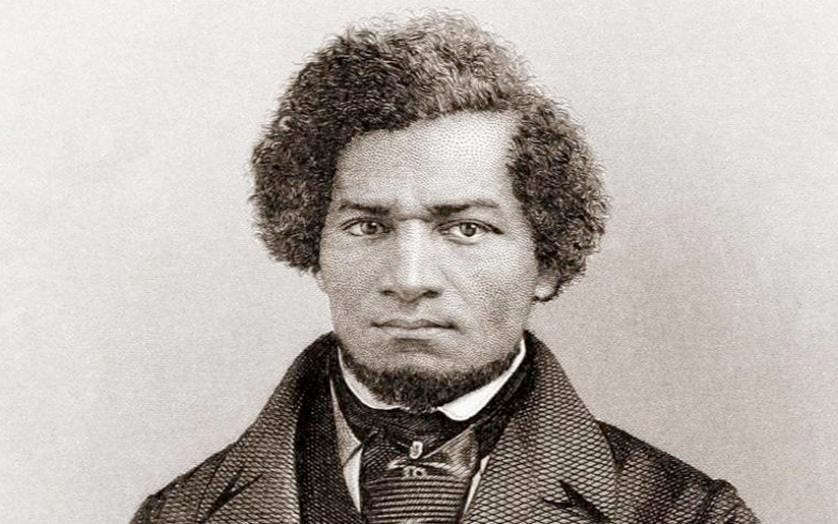

Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King Jr. are arguably the two Americans most responsible for the abolition of slavery and segregation, respectively. Both were devout Christians who grounded their campaigns for racial justice in Christian teaching — specifically, the concept of imago Dei, the idea that human beings were created in the “image of God.” This means that every person has inherent value and worth.

Consider how Douglass laments slavery’s evil: “Slavery is wicked” because “it contravenes the laws of eternal justice” and “mars and defaces the image of God.” For his part, King claimed that every man, Black or white, is valuable in God’s eyes “precisely because every man is made in the image of God.” Imago Dei sounds like an obscure theological concept, but really, it’s the belief that God made all people equal.

Our cultural inheritance from Christianity makes it easy for us to endorse equality as an obvious good. But we shouldn’t take it for granted. In the course of history, the idea that all people are created equal is an anomaly. Many other societies, and even some of the ancient forebears of our own, believed in caste and hierarchy. (Aristotle, for example, thought that slavery was the natural condition of certain human beings.) Imago dei is a quintessentially Christian claim.

Even the Declaration of Independence expresses this idea when it says that “all men are created equal.” King recognized this as Imago Dei: “You see, the founding fathers were really influenced by the Bible.” Long before the nation lived up to Imago Dei, patriots like Douglass and King had high hopes for what the country could one day become, because the promise of God-ordained equality was enshrined in its foundations. The very specific promise of Imago Dei guided them every step of the way.

2. Racial injustice is thoroughly un-Christian.

Obviously, Christians have done much to inflict harm and perpetuate racial inequality. So-called Christians have supported slavery, segregation, and every racial injustice under the sun. Douglass, who criticized Christian hypocrisy while remaining a fervent Christian himself, made a distinction between “the slaveholding religion of this land” and true Christianity. “I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt… and hypocritical Christianity of this land.” King shared similar sentiments, and thought that many nominal Christians in his day were falling far short of the call of Christ.

Christianity doesn’t excuse injustice and hypocrisy. As the late pastor and theologian Tim Keller argued in The Reason for God, we have the resources within Christianity itself to make sense of injustices committed by Christians. The lens of Christianity provides us with the moral clarity to recognize the things that are truly evil and condemnable.

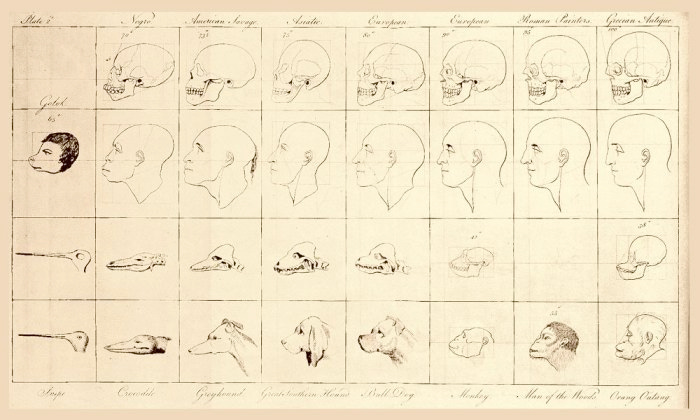

This could be compared to how we look to science to reject bad science. In the early 20th century, racism permeated the sciences. In the fields of biology, sociology, and anthropology, racist scientists commonly argued that white people were superior to other races. Today, we have rejected this as pseudoscience; we don’t reject the practice of science altogether, nor do we turn a blind eye to the racist myths that were once perpetuated. We instead see those scientists as bad actors, and their terrible errors as thoroughly unscientific. In the same way, when it comes to the history of racist corruption in the church, we can and should reject that as pseudo-Christianity; we don’t have to choose between abandoning the Christian faith and turning a blind eye to the evils committed by Christians throughout history. We might see those Christians as bad actors, and their terrible errors as thoroughly un-Christian.

From An Account of the Regular Gradation in Man and in Different Animals and Vegetables; and from the Former to the Latter (1799), a work of “scientific” racism by Charles White.

And while it’s easy for people in America today to see Christianity as a white man’s religion, Christianity — in the context of history or as seen in the global portrait of Christians today — is the largest, most diverse movement in all of human history.

3. The Christian view of reality provides the best basis for justice and morality.

Christian theology gives us the strongest moral vocabulary for racial equality. The clearest explanation for why human beings deserve justice in the first place comes from Christian teaching. This becomes clearer if we take away the Christian view. When we hollow out the belief that all people are image-bearers, it is easy to slide into Social Darwinism (the view that people, like animals, have no purpose beyond survival of the fittest). The moral logic behind equality, social safety nets, and protections for the very young and the very old then becomes far less obvious.

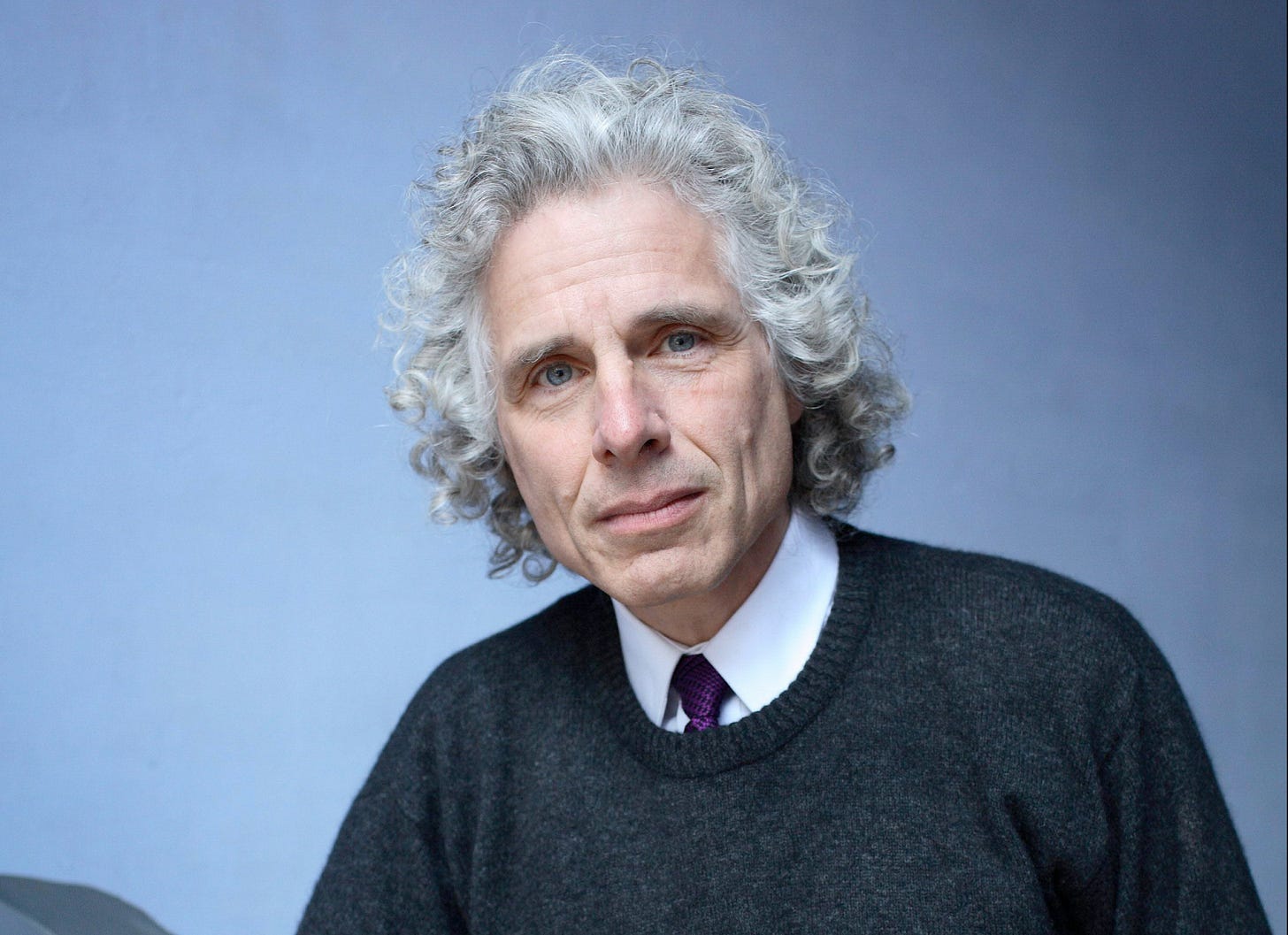

A proper atheist might believe that we are no more than smart apes. Collections of atoms. Clumps of organized dust fortunate enough to have some brain activity. If that is all we are, why should anyone deserve civil rights? Why should equality and the alleviation of poverty be goals? Why should there be protections for the very young, the very old, or anyone else we might consider unuseful? If we believe in survival of the fittest, shouldn’t we just discriminate against the less fit and let evolution do its thing? Leading scientific atheists themselves have said so.

World-famous atheist and cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker has argued that neonaticide, the “killing of a newborn” on the day they are born, is an adaptive behavior, since the “biological value” of a child increases as the child grows up. Pinker was not endorsing neonaticide, and indeed he condemned it as wrong, but he says he can’t find any grounding for this moral view in human biology. Instead, he emphasizes the difficulty of locating scientific reasons to protect all human life and is more sympathetic toward parents who kill their newly born children than toward people who commit other kinds of murders. This is, needless to say, very far from the ethic of imago Dei, which holds that the worth of people does not depend on the ageist and ableist measure of “biological value” or anything else besides the fact that they are human in the first place.

Pinker, when discussing neonaticide, feels it is wrong, but he admits that he can’t argue that it is actually wrong. Douglass and King, on the other hand, could not only feel slavery, segregation, and racist mistreatment were wrong, but they could argue why they were wrong. They argued the dignity and worth of all human persons is a reality that demands dignity and respect. In Christendom — a time when Christianity was dominant in American culture — they appealed to shared biblical truths. Without this, Douglass and King wouldn’t have had much of a case to make. They could have asked for sympathy or kindness or pity, but they couldn’t have made claims about what “justice” demands or what is “right” if it hadn’t been widely believed that all people were truly equal and thus deserving of equality. In the story of American history, the Christian view of reality was necessary in advancing racial equality.

I’m not at all suggesting that people who are nonreligious or atheist are typically immoral, or that they haven’t done anything for racial equality and other social causes. They have. In fact, many people who are without religious beliefs have adopted social causes and “making the world a better place” as a kind of substitute religion — their mission during their time on earth. But that doesn’t mean their ethics make sense: they are committed to a morality that isn’t in line with their view of reality.

I’m glad that the desire to be a good person and make a difference is popular among the nonreligious, and I’m glad that racial justice advocacy is in vogue, but I have doubts about relying on mood rather than conviction; this couldn’t have provided a robust enough ethical or intellectual case for the racial progress made in centuries past. Without a Christian ethic, we are lacking the most vital truths and advocacy tools of our predecessors.

The cause of justice that we are still advancing today is a continuation of the cause of Christianity itself. Many of us carry on because we are Christians. But whatever someone’s personal beliefs, and whether they realize it or not, those who advocate for racial equality are championing an idea that Christians can celebrate as our very own.

Marie, I have enjoyed your articles in The Preamble. Generally, they are thoughtfully written, and your strong sense of justice resonates with me. Often, I come away with a deeper understanding of historical context and current realities. I appreciate when you link sources, so that I can delve into them, and not solely rely on one author.

I found myself disagreeing with many of the points you made in this article. For example, your assertion that non-Christians or the nonreligious do not have convictions. Also, when you seemed to suggest that Christians were the first, and possibly only, group to believe in justice and equality. I invite you to learn more about other religions, including those that precede Christ and Christianity, some by thousands of years. I also encourage you to learn about philosophers, both modern and ancient, and their contemplations on ethics and moral behavior.

It is evident that you have come by your sense of justice and morals from your Christian faith. I hope that you might come to know that there are people who have morals and ethics, some not that dissimilar from your own, that they came by from a different source. A source that is not inferior to your own. We make better allies when we understand and appreciate each other.

I look forward to your future articles.