The Day Black America Left the GOP

The long, turbulent story behind how Black voters transformed American politics — and why their loyalty endures today.

Today, it’s widely known that most Black voters tend to support Democratic candidates, but this was not always the case. Black Americans were once much more likely to be Republicans.

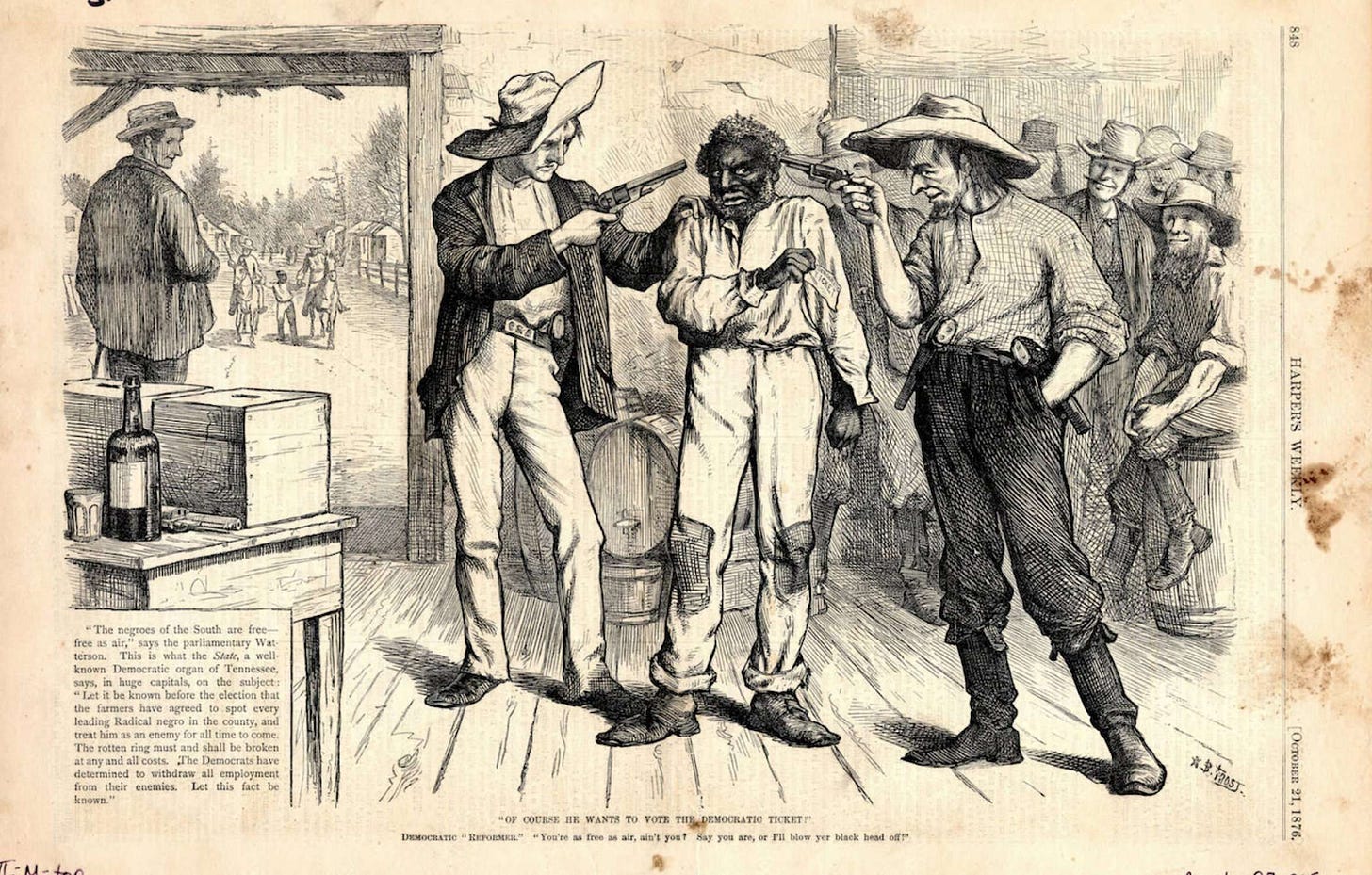

On paper, Black men everywhere gained the right to vote in 1870, and Black women in 1920. Over this period, Black citizens in the North were increasingly able to cast their ballots. But due to racist practices and barriers, Black Americans in the South didn’t gain full access to the vote until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which finally cleared away obstacles like poll taxes and literacy tests.

As Black Americans gained access to the vote, they stuck with the party that had advocated for their rights: the Republican Party. “The Republican Party was the party that fought for the abolition of slavery — the ‘Party of Lincoln,’” explains La TaSha Levy, a Black studies scholar. In fact, “for generations, so many Black families couldn’t fathom being Democrats, since that was the party of white segregationists and white supremacists.”

Today, Black voters are the most reliably Democratic voting bloc of any racial group in America — with between 80% and 90% consistently voting Democratic, according to data from the Pew Research Center.

So what changed in the century following Reconstruction and swayed Black voters to abandon the Republican Party?

The Depression Era Shift (1930s to 1950s)

In the 1930s, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal presented solutions to widespread unemployment and financial instability, and it became the economic lifeline for a nation suffering from the Great Depression. His second New Deal (which included Social Security and aid to tenant farmers and migrant workers) was hugely popular with all voters, but especially poor ones.

Because of the New Deal, some Black voters were drawn to the Democratic Party, but many couldn’t be persuaded to abandon the Republican Party, knowing that the Democrats also stood for segregation in the South. This sentiment gradually started to change, but the big wave of Black support for Democratic candidates wasn’t until the 1960s.

JFK Helps MLK (1960)

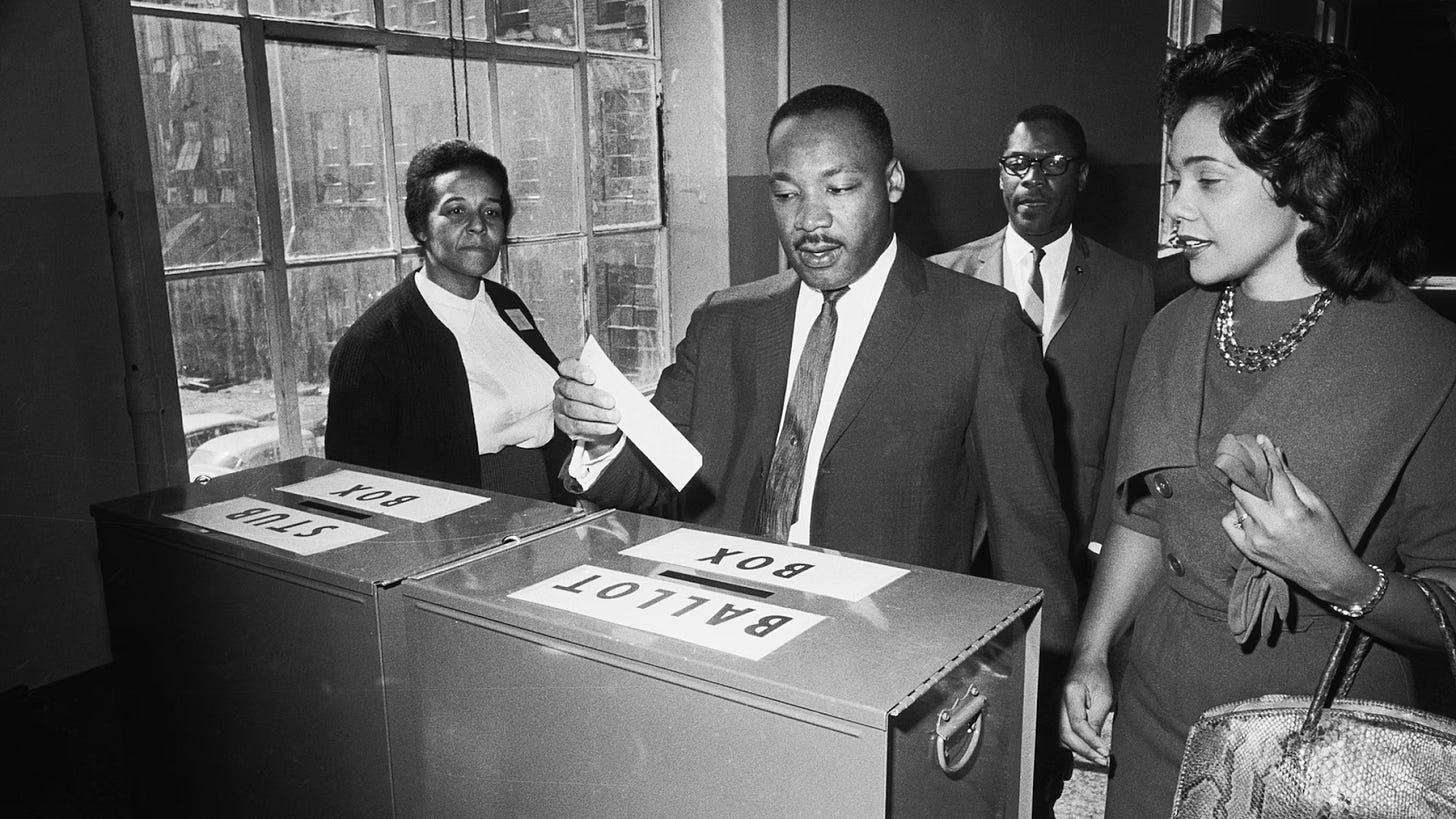

In that year, the Democrat John F. Kennedy was running for president against the Republican Richard Nixon. Nixon was seen as having a slight edge on civil rights, and Kennedy had ground to make up with Black voters. Just weeks before the election, Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested while leading a sit-in in Atlanta. Judge J. Oscar Mitchell, a Democrat, sentenced him to four months of hard labor for a separate crime of violating probation on a traffic violation. King would be doing grueling work alongside white prisoners in a notoriously racist part of the South.

After a phone call with King’s wife, Coretta, Kennedy pulled some strings and managed to secure his release. Following this incident, King expressed his gratitude, while adding, “I might say that there are no political implications here” and concluding Kennedy must have been acting simply out of goodwill. King’s father, however, took Kennedy’s gesture to heart and offered a strong public endorsement of Kennedy.

Martin Luther King Sr. was a lifelong Republican and an influential figure as the senior pastor at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, so his wholehearted support was significant. “The publicizing of this endorsement, combined with other campaign efforts, contributed to increased support among Black voters for Kennedy,” according to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

Ultimately, about two-thirds of African Americans voted for Kennedy, while about one-third voted for Nixon. Kennedy became president, and he had Black voters to thank for it. “On Election Day, if blacks hadn’t turned out for him in large numbers, Kennedy might have had to deliver a concession speech,” writes Steven Levingston in his book Kennedy and King. “In Illinois, for instance, where he topped Nixon by 9,000 votes, 250,000 blacks voted for Kennedy. In Michigan, he won the votes of another 250,000 blacks and carried the state by 67,000 votes. In South Carolina, he carried the state by 10,000 votes with 40,000 blacks casting ballots for him.” Black voters decided the election, and they decided to put a Democrat in office.

The Fight for Civil Rights (1964)

Although the majority of Black Americans voted Democratic in 1960, it was the 1964 election that cemented their support decisively. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, a federal law extending equal rights to African Americans, had just been passed.

The majority of Republican senators supported the Civil Rights Act, but the Republican nominee for president, Barry Goldwater, was in the minority that voted against it. Political historian Leah Wright Riegeur explains, “Everything that the Republican Party [did] up until that moment” to fight for equality for African Americans was “undermined and compromised by the fact that the party nominate[d] a senator who voted against the Civil Rights Act.”

Goldwater had a personal record of favoring integration but didn’t support federal policies toward that end. He said he couldn’t support the Civil Rights Act because he felt the act was unconstitutional; he was a firm believer in states’ rights and leaving “the problem of race relations… [to] the people directly concerned.” He argued in his 1960 book, The Conscience of a Conservative, that “social and cultural change, however desirable, should not be effected by the engines of national power.” Case in point: though he personally deemed integrated schools “both wise and just,” he considered Brown v. Board of Education an overreach of the federal government.

Black voters saw that Goldwater did not support measures to ensure their full equality. At the time, King said, “I feel that the prospect of Senator Goldwater being president of the United States so threatens… our nation that I can not in good conscience fail to take a stand against what he represents.” Black Americans voted overwhelmingly for Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson, who won in a landslide. If the 1960 election prompted a mass exodus of Black Americans from the Republican Party, the 1964 election completed it.

The Southern Strategy (1970s)

Republicans could no longer win more than a very small share of Black voters, so they now had little to lose with Black voters. They could simply strengthen their support among white Americans. Starting with Nixon, who was elected president in 1968, the Republican Party employed the famous “Southern strategy” — a tactic to capitalize politically on prejudice and resentment of African Americans. Nixon popularized the term “law and order” and declared a “war on drugs” in 1971, which one of his advisers later admitted was a plan to criminalize Black Americans and vilify them in the media, using coded language to push racist tropes.

Reagan mimicked Nixon’s racially coded policies. In 1986, the Reagan administration introduced the Anti-Drug Abuse Act and, with it, an inexplicably different punishment for the same drug in two forms, with minimum sentencing 100 times more severe for crack compared with powder cocaine (crack being the form more common in communities of color).

For the rest of the 1980s and ’90s, Republicans campaigned on being “tough on crime” and accusing Democrats of being “soft” on crime. This pressured Democratic presidents to pull from their playbook, as when President Bill Clinton’s 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act introduced “three strikes, you’re out” — drastically harsher mandatory minimum sentencing aimed at keeping Black and brown “superpredators” locked up for life. These policies, all descended from the Southern strategy, leveraged racist stereotypes and fear to win political support from white Americans.

Differences Among Black Democrats Today

Since Black Americans overwhelmingly support the Democratic Party, their politics can seem uniform if we look only at party affiliation. But partisanship doesn’t capture the full picture. For instance, summarizing a finding by the National Election Study, FiveThirtyEight reports that most African Americans take the liberal position on some government spending, like job guarantees (53%) and health insurance (61%), but an even greater share take the conservative position on other government spending, with 84% saying that the government should spend more money to deal with crime. These cross-party positions are “masked when we focus solely on Black partisanship.”

FiveThirtyEight also notes that there is “much more diversity in Black Americans’ ideological identities than in their partisan identities.” In a 2016 survey, Black Americans surprisingly self-identified as liberal and as conservative in about equal shares (45% versus 43%, respectively). The researchers concluded that Black Americans don’t conceptualize “liberal” and “conservative” in the same way as white Americans, nor do they sort their beliefs into these categories as neatly.

Researchers Chryl Laird and Ismail White co-authored the 2020 book Steadfast Democrats to demystify why so many Black Americans, despite being moderate or conservative, still vote Democratic. Through experiments and analysis, they determined that for many, allegiance to the Democratic Party is tied to Black identity. Supporting the Democratic Party, despite having diverse and wide-ranging convictions, has become a way that Black Americans pool their political power and present a unified front.

Black voters have played a huge role in elections, given that no candidate has won the Democratic presidential nomination since 1992 without a majority of the Black vote. Black Americans who view modern-day racism against Black people as a defining issue find that Democrats largely share that concern. Many Black voters perceive that Republicans believe that racial inequality is no longer a pressing issue — and that their rhetoric on race echoes racist dog whistles of the past. Republicans have thus lost most of the allegiance of Black voters.

Black Americans had to fight for the right to vote, overcoming centuries of virulent racism — and though there is not one monolithic “Black vote,” such extreme historical obstacles mean they share a common cause, which has led them to vote together frequently and powerfully.