The Court's Next Big Decision on Race

And why it could make protecting Black voters unconstitutional.

Today’s newsletter is written by Leah Litman, a professor of law at the University of Michigan and a former Supreme Court clerk.

For six decades, the United States has tried to set right a fundamental wrong: the fact that for hundreds of years, it systematically excluded people of color from participating in the American experiment. Enslavement may have been outlawed post Civil War, but it was speedily replaced by repressive Black codes and Jim Crow laws, all aimed at ensuring that Blacks and other racial minorities were never able to claim their birthright: equality under the law.

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) sought to change that. And now, the Supreme Court is getting really bent out of shape about discrimination. Just not the discrimination you might think.

There’s a consequential case involving the VRA that the Court is poised to decide before the end of June, Louisiana v. Callais. In Callais, the justices are noodling over this question: Is trying to comply with the Voting Rights Act unconstitutional? Specifically, is it unconstitutional racial discrimination?

If that question strikes you as odd, this isn’t the first time this Court has engaged with it, and it’s not even the first time the Court has developed an affinity for toying with the implications. Take the Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder, where justices said that one of the key provisions of the VRA was unconstitutional. In an effort to keep states and municipalities that had historically perpetrated voter discrimination from continuing with their behavior, the VRA required those locations to ask in advance, or get preclearance, before making changes to voting.

In the Shelby decision, John Roberts wrote that the preclearance system violated the principle of equal sovereignty, which supposedly required Congress to treat all states the same. The preclearance process, he maintained, was an unfairly punitive concept that subjected the former Confederacy (and other places with similar attitudes historically) to “disparate treatment” — a legal term that describes, you guessed it, discrimination.

In Shelby, the justices now depicted the VRA as a form of unconstitutional discrimination.

This wasn’t the first time the Republican Party had levied that charge against the VRA. Before Chief Justice Roberts said the VRA punished the South, segregationist Strom Thurmond opposed the Voting Rights Act when it was passed in 1965, labeling it punitive. Ronald Reagan argued much the same when he opposed expanding the VRA, calling the law vindictive, selective, and “humiliating” to Southern states.

Which brings us to Louisiana v. Callais. The case concerns Section 2 of the VRA, which prohibits discrimination in voting nationwide, including cases where states adopt voting laws or policies that negatively impact voters of color, even if they do it unintentionally.

Callais arose out of litigation over whether Louisiana’s 2020 voting redistricting drew district lines in a way that split up Black voters, thereby reducing their political power as a voting bloc.

Voting districts are redrawn after every census, and since the last redistricting in 2010, Louisiana’s Black population increased, while the state’s white population decreased. By 2020, Black voters made up about one-third of Louisiana’s population, but Louisiana drew districts in a way that allowed districts dominated by whites to choose five members of Congress, while Black voters only had majority representation in one district.

This move violated the VRA, the plaintiffs said, and Louisiana eventually gave up the fight, conceding it had violated the VRA, and asking the federal courts for another chance. The state wanted to draw a new set of maps that complied with the VRA, rather than have a court do it for them.

So Louisiana again set about the task of redrawing its districts. The state legislature weighed different considerations like natural boundaries, waterways, and partisan considerations, like whose seats they wanted to protect and whose they’d be willing to make more vulnerable. (Notably, the legislature opted to protect the seat of Speaker of the House Mike Johnson.)

And therein lies the (supposed) problem. A group of white voters argued that Louisiana’s efforts to comply with the VRA are nothing more than unconstitutional race discrimination.

Their argument proceeds as follows: the VRA prohibits states from drawing districts in ways that deny Black voters reasonable political opportunities to elect the candidates of their choice. A legislature might do this by splitting potential coalitions of Black voters into multiple districts where they would be in the political minority rather than keeping the voters together in a district or two where they could be in the political majority.

To avoid violating the VRA, a legislature therefore has to consider whether it would be possible to abide by the state’s redistricting criteria and preserve Black voters’ political opportunities.

That’s where the problem is, according to the white voters: They argue that even attempting to provide Black voters political power discriminates against the white voters (who feel entitled to possess the political power they would have under a different set of districting rules that ignored Black voters and erased Black voters’ political opportunities).

And the Republican-appointed justices on the Court might agree with them. During the oral argument in the case, the Chief Justice declared that one of the two Louisiana districts where Black voters could be in the political majority looked like a snake. Justice Gorsuch repeated that same characterization.

They were insinuating the state’s oddly shaped, convoluted districts were because the state consciously sought to provide Black voters with political opportunities. The reality, however, is that the state picked the somewhat weirdly drawn map to protect the political opportunities for two white politicians– Rep. Mike Johnson, the Speaker of the House, and Rep. Julia Letlow. The NAACP Legal Defense Fund had proposed a districting map with compact districts that also provided Black voters with political opportunities. The problem was that their map made Rep. Johnson and Rep. Letlow’s seats more competitive.

The state admitted so in their briefs – that map "would have kicked either the Speaker of the House, Mike Johnson, or Representative Julia Letlow (who sits on the powerful Appropriations Committee) out of Congress.” And the legislature preferred to disadvantage less powerful, more moderate Republicans. So they did–by selecting the map with the snake-like districts.

Callais, like Shelby County, is an effort to launder white racial grievances against Black voters into the law of the land. The white voters don’t want Black voters to have the political power, and the political opportunities, the VRA provides. To that end, their brief refers to the Black opportunity districts as “odious racial gerrymander[s]” and “a racial quota.”

But it treats white opportunity districts as normal, legal, and something they are entitled to. They urge the Court to say that “Section 2 should no longer supply a compelling interest for racial gerrymanders”; in plain English, they are asking the Court to declare that it is unconstitutional for the Voting Rights Act to try to ensure Black voters have political opportunities to elect the candidates of their choice. The white voters’ arguments in the case parrot a recent executive order from the Trump administration that says that civil rights laws that require entities to avoid policies with detrimental effects on racial minorities are themselves racial discrimination.

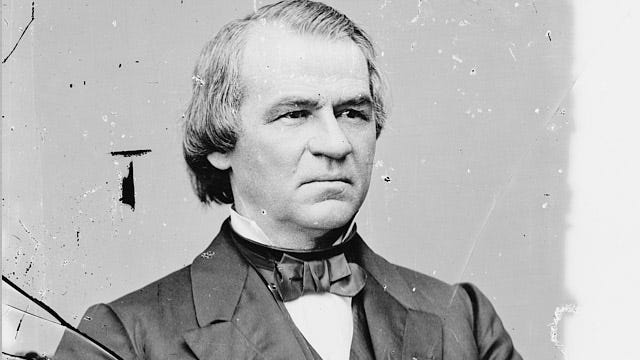

The white grievances against racial equality have an even longer, and uglier lineage that should give courts pause before they embrace legal theories that sound in a similar register. In the aftermath of the Civil War, President Andrew Johnson vetoed civil rights legislation that sought to include recently enslaved Black Americans in society, saying that the laws “operated in favor of the colored and against the white race.” Here too, the claim was that civil rights protections for racial minorities unconstitutionally discriminate against white people.

Yet these arguments have occasionally succeeded in the Supreme Court, even in the initial aftermath of the Civil War. In 1883, the Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which prohibited private entities from discriminating on the basis of race. The majority opinion ranted about how, “when a man has emerged from slavery, there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen, and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws.”

It treated laws prohibiting racial discrimination as giving special treatment to Black Americans—at the expense of white people. That is the same structure of the argument in Callais: The theory views laws that prohibit racial discrimination against Black voters as illegal discrimination against white voters.

In my new book, Lawless, I write in greater detail about how the Supreme Court has sometimes ceded the law to white voters’ feelings of entitlement and racial grievance. Part of why I characterize the Court as lawless is that some justices are, in case after case, taking vindictive, antidemocratic talking points about race and helping to codify them into the law of the land. And they may be on the cusp of doing so once again in Callais.

Leah Litman just released her first book, Lawless: How the Supreme Court Runs on Conservative Grievance, Fringe Theories & Bad Vibes, which is already a New York Times Bestseller. Leah also co-hosts the podcast Strict Scrutiny and writes frequently about the Court for The Washington Post, Slate, and The Atlantic. You can buy Lawless here.

Great piece from Leah! I was not aware of this case. It’s absolutely another devastating example of how White Supremacy is the root problem for America. Nearly every issue we have can be traced back to it, and until we pull this root out for good, we will continue to all be negatively impacted.

I’m heartbroken at the state of our democracy. The Supreme Court has already ruled that partisan gerrymandering is fine. I have no faith that they will uphold the hard won legislative victory of VRA. https://www.npr.org/2019/06/27/731847977/supreme-court-rules-partisan-gerrymandering-is-beyond-the-reach-of-federal-court