The Bircher Playbook

Why the John Birch Society’s playbook outlasted its critics — and how it led to the crises now shaking the right.

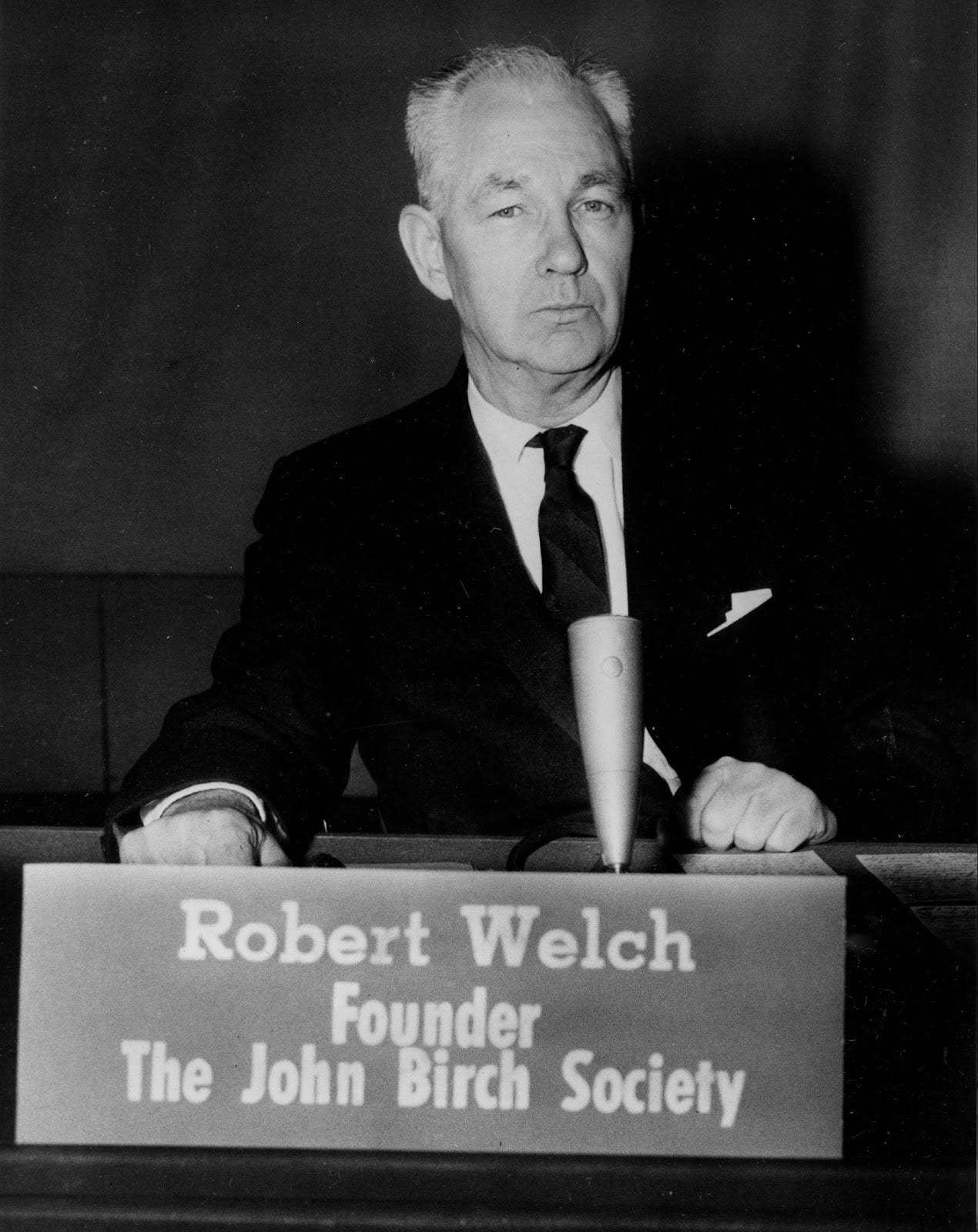

On a frigid December morning in 1958, eleven of America’s wealthiest businessmen gathered in a Tudor mansion in Indianapolis for a secret meeting. The host, candy magnate Robert Welch, had a warning: a vast communist conspiracy had infiltrated the highest levels of American government. The traitors included President Dwight Eisenhower.

Though it sounds like a fringe conspiracy theory, this wasn’t a gathering of cranks. Fred Koch, founder of what would become Koch Industries — now one of America’s largest private companies, led by his sons Charles and David, who became major Republican donors — sat in that room. By the time they left two days later, they had founded the John Birch Society, named for a Baptist missionary killed by Chinese Communists in 1945. Their mission: to save America from enemies within — communists, liberals, internationalists, anyone pushing what they saw as collectivism and federal overreach.

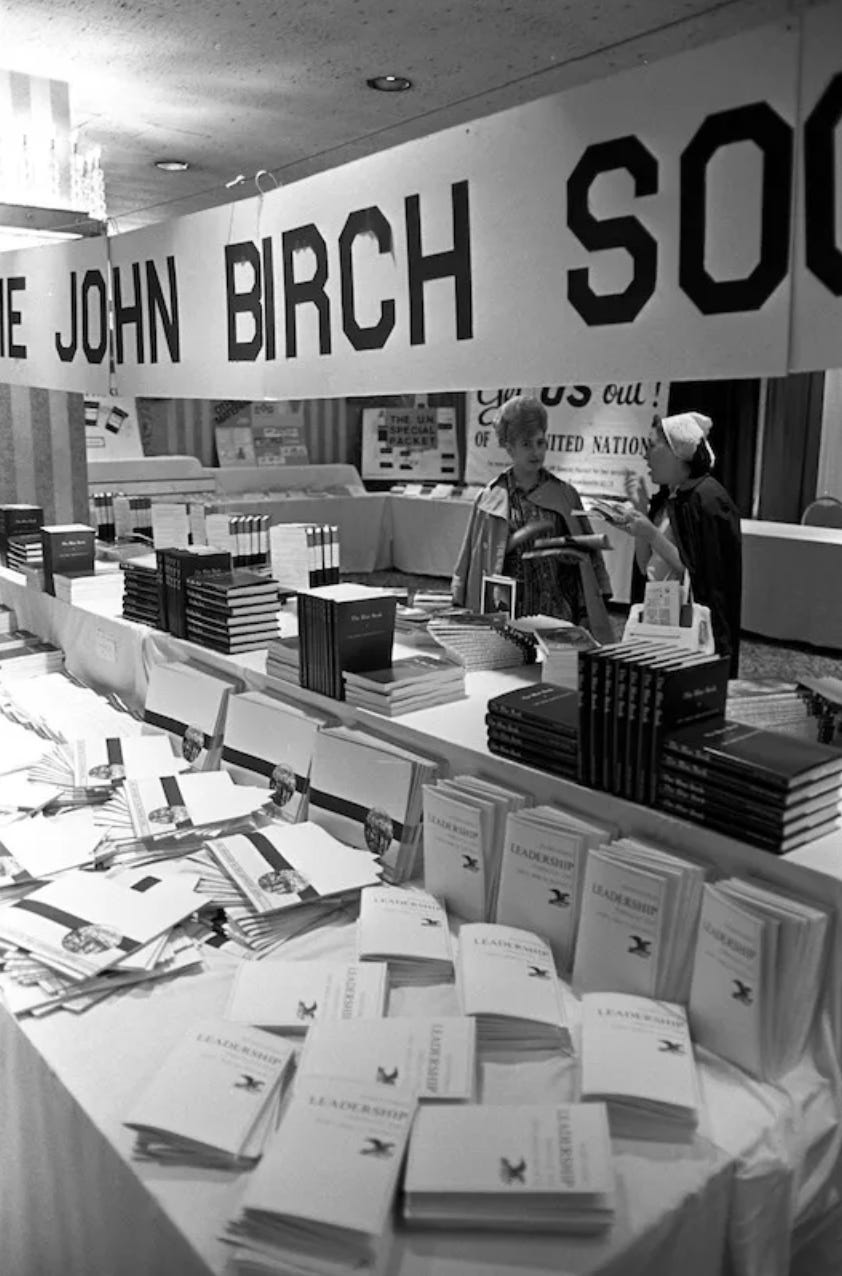

At its peak, the society claimed 100,000 members. They opened 400 bookstores, published magazines, and flooded Congress with coordinated campaigns. Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater observed that in Phoenix, “every other person” was a member. These weren’t marginal figures. They were, in Goldwater’s words, “the highest cast of men of affairs.”

The Birchers didn’t just oppose communism. They opposed the entire architecture of postwar governance. And in that opposition, they built a template that would reshape the Republican Party for generations.

The Bircher worldview

Start with their enemies list. The United Nations was “an instrument of Communist global conquest,” Welch wrote in The Blue Book of the John Birch Society. Chief Justice Earl Warren was a traitor whose support for desegregation proved communist influence; “Impeach Earl Warren” billboards lining American highways were Birch productions. The Civil Rights Movement? A Kremlin plot. Martin Luther King Jr. was a communist agent.

Then there was fluoride. The society thought that adding it to water supplies was communist poison, a “wedge for socialized medicine,” according to historian Matthew Dallek, author of Birchers: How the John Birch Society Radicalized the American Right. The paranoia worked: communities across America rejected fluoridation because of John Birch campaigns.

Welch made his most explosive claim in a letter to friends: President Eisenhower was “a dedicated, conscious agent of the Communist conspiracy.” That’s right — the hero of D-Day was secretly working for Moscow.

The Birchers pioneered what Dallek calls “an alternative political tradition on the far right.”

Where mainstream conservatives supported NATO and international engagement, the Birchers embraced isolationism. Where conservatives argued for limited government through constitutional principles, the Birchers saw conspiracies everywhere. Where conservatives often used dog whistles on race, the Birchers were explicit about their opposition to racial integration and civil rights.

What they achieved

Only a handful of Birchers became members of Congress over the organization’s entire history. But electoral victories weren’t the measure of their influence.

They moved the culture. The campaign to “get US out of the UN“ planted deep skepticism about international institutions that persists today. The attacks on Chief Justice Warren energized opposition to federal civil rights enforcement. The resistance to integration, framed as resistance to federal overreach, became Republican orthodoxy in the South and beyond.

Birchers shaped conservative politics with apocalyptic rhetoric. As Welch wrote, this was a conflict “between light and darkness; between freedom and slavery; between the spirit of Christianity and the spirit of the anti-Christ for the souls and bodies of men.” Every policy debate became existential.

The society demonstrated that intensity mattered more than numbers. One hundred thousand committed activists, organized into disciplined local chapters, could dominate school boards, flood representatives with mail, and define debates in ways millions of voters could not. The model worked.

They showed there was a market for conspiracy-driven politics. Far-right broadcaster Alex Jones — who built an empire on conspiracy theories through his InfoWars platform — has said that his father was a Bircher and the society’s influence shaped his worldview. The conspiracies changed over decades, but the logic remained consistent: secret elites are destroying America from within.

Most important, the John Birch Society established that the Republican Party would tolerate extremism if extremists delivered votes. Party leaders denounced Welch’s claims that Eisenhower was a communist traitor but still courted Birch members for their energy and money. That bargain — accept the activists, ignore their most embarrassing statements, benefit from their organizing — became the Republican playbook.

Buckley’s dilemma

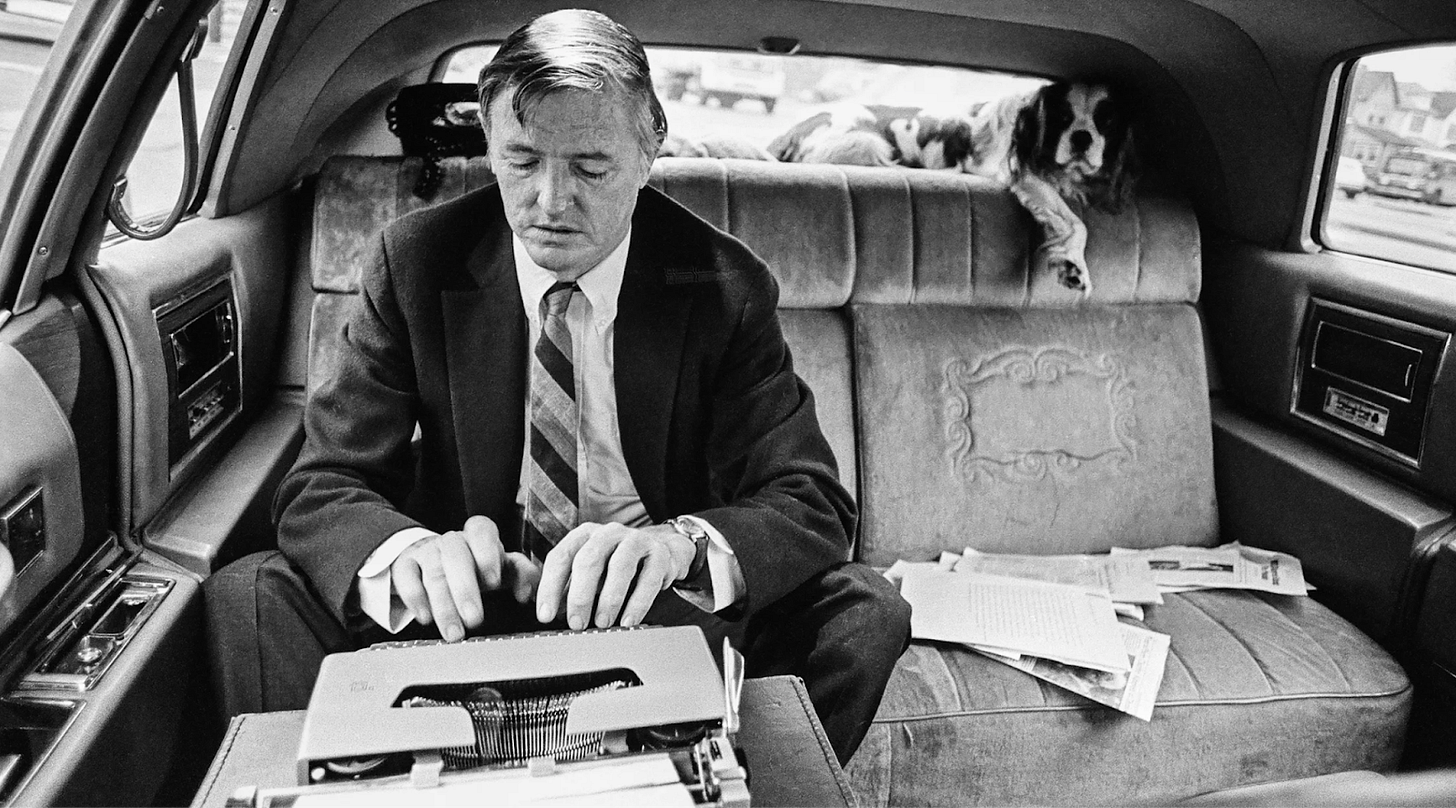

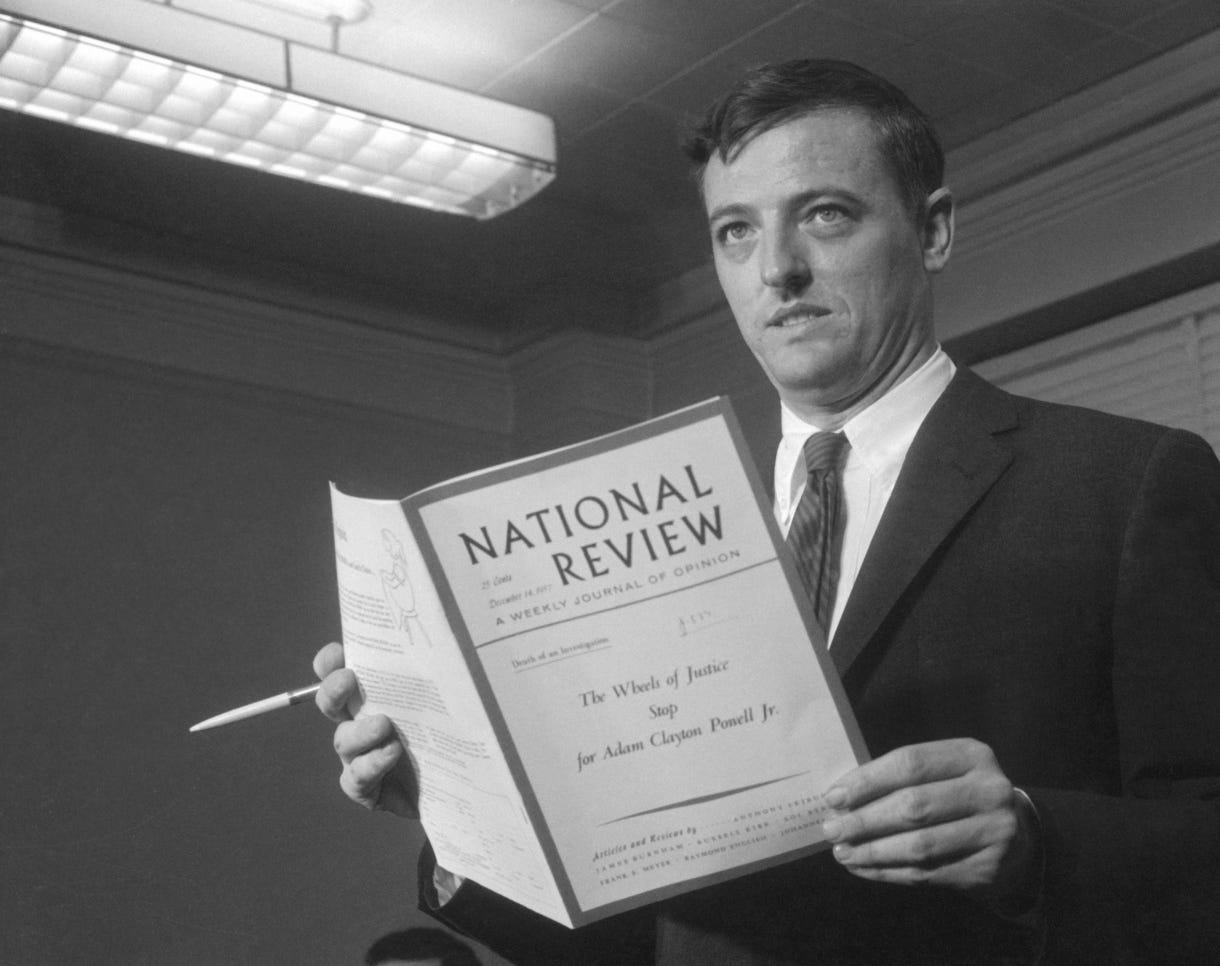

All of this created a difficulty for William F. Buckley Jr., who founded National Review in 1955 to build an intellectually serious conservative movement. He wanted conservatism to win elections and shape policy. He needed it to be respectable.

The Birchers were a problem. Buckley had personal ties to the movement. His mother was a member of the society, and Welch had been an early financial supporter of National Review. But Welch’s conspiracy theories — particularly his claim about Eisenhower — were toxic. If conservatism became synonymous with Bircher paranoia, moderates would flee and the movement would remain on the fringe.

In February 1962, Buckley published “The Question of Robert Welch” in National Review. The editorial was carefully calibrated. Welch’s theories were “damaging the cause of anti-Communism” by associating that cause with “crank assertions divorced from reality.” But the editorial avoided attacking the society itself or its members, many of whom Buckley called responsible conservatives.

The response was immediate. Birch leaders sent angry letters accusing Buckley of betraying the movement. Buckley had tried to thread the needle — criticizing Welch while praising the society’s members. “I don’t think in my life I have made a single unfavorable reference to any members of the John Birch Society,” Buckley wrote to one of the group’s founders. It didn’t work: National Review still lost subscribers. Donors withdrew support.

By 1965, as Birchers increasingly opposed the Vietnam War because they believed the conflict was a communist plot to weaken America, Buckley sharpened his criticism. He warned that association with Birchers would doom conservative candidates.

Even though conservatives like Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford, who once supported the Birchers, ultimately disavowed the group, their ideas persisted. Over time, the John Birch Society left its imprint on the Republican Party, pushing it toward more hardline positions on anticommunism, white supremacy, isolationism, and nativism. The Society’s early focus on what would become known as the culture wars established a template for subsequent conservative movements. From the Moral Majority — founded by Baptist minister Jerry Falwell in 1979 to mobilize conservative Christians as a political force — through the Tea Party movement of the 2010s, to the MAGA movement, each recognized and amplified the cultural battlegrounds the Birchers had identified decades earlier.

“The Birchers helped forge an alternative political tradition on the far right and that the core ideas were an anti-establishment, apocalyptic, more violent mode of politics, conspiracy theories, anti-interventionism and a more explicit racism,” Dallek said. “They were some of the first people on the right to take up questions of public morality, of Christian evangelical politics — banning sex education in schools, trying to insert what they called patriotic texts into libraries and into the classroom. And so they were quite early to even the issue of abortion.”

Since Donald Trump’s election in 2016, many historians and pundits have pointed to the history of the John Birch Society as the throughline that connects Trumpism to the birth of the conservative movement, casting Trump as the logical culmination of the movement rather than as its gravedigger.

The lesson we ignored

The Republican party faces a new group of extremists in its ranks today: the ”Groyper” movement led by white nationalist Nick Fuentes, who famously began a speech by saying, “I love you, and I love Hitler.”

The Groypers take their name from a variant of the Pepe the Frog meme used among extremist groups. The Anti-Defamation League describes them as “alt-right, white nationalist, and Christian nationalist activists” promoting antisemitic, racist, and homophobic views cloaked in talk of traditional values.

Where the late Charlie Kirk built a broad coalition that could win elections and influence policy, Fuentes prioritized racial politics and accelerationism over political viability. In 2019, his followers disrupted Turning Point events, heckling Kirk with provocative questions about immigration and LGBTQ rights — issues on which they thought he was too moderate and willing to compromise.

Four years ago, Fuentes was banned from nearly every platform for hate speech and encouraging the January 6 rioters. Now he has over a million followers on X and, at 27 years old, sits at the center of a civil war over conservatism’s future.

Fuentes makes no bones about his views. In a March podcast, he said, “Jews are running society, women need to shut the f*** up, Blacks need to be imprisoned for the most part, and we would live in paradise.”

Far-right broadcaster Tucker Carlson — Fox News’s most-watched personality before his 2023 firing — recently hosted Fuentes for a friendly interview that drew five million views. Carlson didn’t challenge Fuentes on his praise of Hitler. He didn’t ask why Fuentes thinks Jewish broadcaster Mark Levin should be deported for his support for Israel. The conversation was cordial.

The interview sparked backlash. Ted Cruz and conservative influencer Ben Shapiro condemned it. But Kevin Roberts, president of the Heritage Foundation, a prominent conservative think tank, initially defended Carlson and blasted the “globalist class” for its criticism. Jewish groups and Heritage staffers said the phrase played on antisemitic conspiracy theories. Roberts’s chief of staff resigned. Heritage held an all-hands meeting. Roberts eventually backpedaled, calling Fuentes “evil” — but still won’t criticize Carlson directly.

For the GOP, this is a Buckley moment. Do you draw a line? Do you say certain figures, certain ideas, are incompatible with the movement? Or do you equivocate, hoping to keep the activists engaged while avoiding their most embarrassing associations?

Vice President JD Vance posted that “the infighting is stupid” and called for unity. But the question isn’t about unity. It’s about values and boundaries.

The monster the GOP created

The conservative establishment that embraced Buckley chose equivocation in the 1960s. They criticized Welch but courted his members. They wanted the energy without the extremism, the donations without the embarrassment, the votes without the associations. They told themselves they could manage the fringe, harness it, keep it useful but contained.

Sixty years later, the fringe is the movement.

As Dallek noted, “the GOP establishment’s efforts to court this fringe and keep it in the coalition allowed it to gain a foothold and eventually cannibalize the entire party.” Robert Welch’s vision — a Republican Party hostile to international institutions, suspicious of democracy itself, animated by conspiracy theories about internal enemies, willing to accommodate explicit racism and antisemitism in service of political power — has won. Not because the John Birch Society survived as an organization, but because the party that tried to marginalize the Birchers while courting their voters eventually became indistinguishable from them.

Buckley understood that intellectual purity mattered. That conservatism needed boundaries. That some ideas weren’t just wrong but poisonous. When he stepped down as National Review editor in 1990, he told The Washington Post his greatest achievement was the “absolute exclusion of anything antisemitic or kooky” from the conservative movement.

Yet you cannot build a coalition on extremism and expect moderation to prevail. Once you accept activists who believe in vast conspiracies, who see enemies everywhere, who reject democratic norms when those norms produce outcomes they dislike, you can’t contain them. They don’t go away when you criticize their leaders.

Perhaps conservatives should have done more to expel the Birchers and their ideology 60 years ago. But now it remains to be seen whether today’s conservatives will learn anything from that failure that is repeating itself with Tucker Carlson and Nick Fuentes. Some, like Cruz, seem to understand what’s at stake. But many haven’t made the choice to guard their principles more fiercely than their coalition.

I had no idea that many of the ideas I hear from Republicans in the American west, where I live, came from Birchers. Thanks for writing this piece!

What a great article. From time to time I see Never Trumpers say something like, "If we can just get of Trump, everything will go back to normal." But I believe you are 100% correct when you said, "Sixty years later, the fringe is the movement." The GOP has sliding toward this for a very long time, and fixing it will take more than just getting past Trump.