Texas Kicks Off Redistricting Arms Race

Special session could trigger nationwide rush to redraw House maps

Three weeks ago, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott received a letter from Harmeet Dhillon, the assistant US attorney general for civil rights.

The missive was urgent in tone.

“This letter will serve as formal notice by the Department of Justice to the State of Texas of serious concerns regarding the legality of four of Texas’s congressional districts,” Dhillon wrote.

Texas’s 9th, 18th, 29th, and 33rd districts — all in the Houston or Dallas areas, all plurality-Hispanic, all currently held by Democrats — were unconstitutionally drawn with race in mind to benefit minority voters, Dhillon alleged. She asked Abbott to send her a response on “the State’s intention to bring its current redistricting plans into compliance with the U.S. Constitution”… by the end of the day. No hurry, though.

“If the State of Texas fails to rectify the racial gerrymandering of TX-09, TX-18, TX-29 and TX 33, the Attorney General reserves the right to seek legal action against the State, including without limitation under the 14th Amendment,” the assistant AG threatened.

You might think that Abbott’s response would be equally forceful. Governors generally don’t like the federal government trying to push them around. After all, Dhillon was objecting to a congressional-district map that Abbott himself signed into law four years ago. On top of that, Texas is currently arguing in court that the district lines were drawn without race as a consideration.

Instead, Abbott took a different route: he embraced the Trump administration’s criticism of his own map.

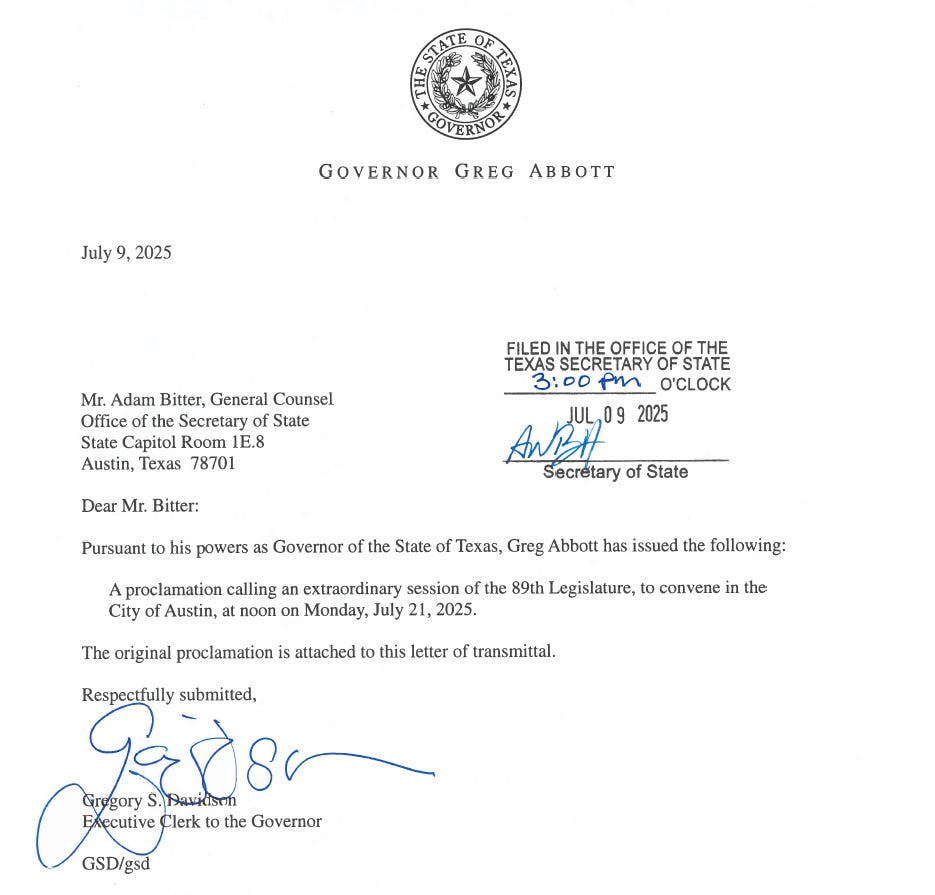

In a proclamation earlier this month, Abbott listed 18 agenda items for a special session of the Texas legislature. Buried towards the bottom of the list? “Legislation that provides a revised congressional redistricting plan in light of constitutional concerns raised by the U.S. Department of Justice.”

It may seem odd for a governor to buckle so quickly to that kind of legal pressure from the federal government, but it helps to understand that this wasn’t really pressure at all. It was a well-orchestrated dance in which everyone played exactly the role they had intended, in order to secure a shared ambition: a brand-new Texas congressional-district map for the 2026 elections.

Normally, redistricting in the US follows a familiar timeline. The census, which counts the total number of Americans across the country, is conducted every decade in the year ending in “0” (e.g. 2020). The population count is then used to apportion the 435 congressional districts among the 50 states, and state legislatures go about drawing their new district lines. These lines are used for the first time in the election year ending in “2” (e.g. 2022) and then continue to be used until the next one (e.g. 2032).

But Texas Republicans didn’t want to wait that long. So, using the Justice Department’s “concerns” as a legal rationale, they are throwing out that script and taking the rare step of redrawing their district lines in the middle of the decade.

Redistricting — the act of state legislators using complicated computer software to slice and dice their voters into odd-looking districts — might not sound particularly interesting. But remember that Republicans wielded only a five-seat House majority after the 2024 elections. And a seven-seat majority after 2022. And Democrats controlled only a nine-seat majority after 2020.

When control of the House so routinely depends on such a small number of seats, any little change matters: even a state making slight adjustments to their map can make a big difference in who ends up with a majority.

As it happens, Texas isn’t looking at only a small change.

Abbott’s special session gaveled in last week, and legislators are under direction from President Trump to massively shift the state’s map in favor of the GOP. Trump has told reporters that he wants the new map to produce five additional Republican-leaning seats.

If Texas moves forward with such a drastic revamping of their congressional-district lines, the number of House seats Democrats would need to pick up to regain a majority in 2026 would double, going from five to ten.

A Texas redraw would also set off a redistricting arms race across the country.

“Two can play this game,” Gavin Newsom, the Democratic governor of California, wrote on X in response to Texas’s redistricting efforts.

Legally, actually, Newsom can’t play this game: California has drawn its congressional district lines by an independent commission since 2010. California Democrats would have to ask voters to do away with the existing redistricting process if they wanted to try to offset the Texas changes.

Newsom isn’t the only governor frantically trying to read up on redistricting law.

On the Democratic side, leaders in New York and Maryland are looking at revisiting their congressional district lines in response to Texas. On the Republican side, Ohio and Missouri are considering plunging into the mid-decade redistricting game as well.

The end result could be a nationwide House map that doesn’t just favor the party in power in each state — but is gerrymandered to the max, with each party trying to squeeze as much of an advantage as they can out of their maps.

It’s unclear which party would win that back-and-forth, but we know who would lose: the voters. Partisan gerrymandering (drawing district lines to benefit a political party) has helped decimate electoral competition across the House map. According to The New York Times, out of 435 districts, only 36 were decided by fewer than five percentage points in 2024.

When state legislators draw congressional-district maps that are heavily gerrymandered, fewer and fewer House members face a competitive reelection contest, making them less and less accountable to their constituents. If members always know they’re going to win, they don’t have to be quite so attentive to their districts. Suddenly, voters lose the best check they have on their representatives. Politicians start to pick their voters, instead of the other way around.

Well, most of the time, that is.

In a 2005 article, a pair of scholars coined the term “dummymander” to describe situations where state legislators go so far in gerrymandering… that they end up hurting their own party.

“If you’re a Republican trying to draw a partisan Republican gerrymander, you’re trying to take Democratic districts and turn them into Republican districts,” Nicholas Goedert, a political science professor at Virginia Tech, explained to me in a recent interview. “But of course, to do that, you have to get Republicans from somewhere.”

A common way to do that is to move GOP voters from a reliably Republican district into a currently Democratic district, in order to turn that district from blue to red. But that also has the effect of making the original Republican district less Republican.

“Now, if you’re taking a 65% Republican district and making it 60% Republican, that's probably fine,” Goedert continued. “That district is still going to vote for a Republican almost all of the time. But if you’re taking a 60% Republican district and turning it 55% Republican or 52% Republican, then you get into a dangerous territory where, yeah, that district, more often than not, will probably vote Republican, but you don’t really necessarily know what’s going to happen in the future.”

“If political circumstances change in some way that you might not have predicted, that district could easily be won by a Democrat.”

Dummymanders, Goedert said, happen when parties “try to slice these districts too thinly” and — in an attempt to make new districts lean their way — end up making the existing districts they hold more vulnerable. Oftentimes, the districts still swing the way they were intended. But in wave years (when one party sweeps into power by a big margin), these 52% or 55% districts often fall to the wayside.

A classic example comes from Texas itself, which got caught in a dummymander during the 2018 Democratic wave.

By its nature, the act of gerrymandering assumes that political conditions will remain constant enough in subsequent years that mapmakers will be able to forecast what will benefit them down the road. That’s how gerrymandering usually manages to suppress electoral competition.

But if the mapmakers are wrong, and conditions shift, suddenly gerrymandering can accidentally increase competition, since one party has handed the other party a bunch of vulnerable seats on a silver platter. In a 2017 article, Goedert called this the “pseudoparadox of partisan mapmaking.”

This pattern could repeat itself in 2026 if either party — especially Republicans, who would historically be expected to have a weak midterm year, as the party that controls the White House — overplays its redistricting hand, or reads the political environment incorrectly. If the GOP tries to mine five new seats in Texas, for example, they will probably be doing so under the assumption that the party’s gains in 2024 among Hispanic voters will continue, and shift more of those voters into their districts.

But those sorts of demographic trends are difficult to be sure of.

Then again, I suppose if their new map doesn’t work out in 2026, the Texas GOP can always pivot before 2028 and draw maps again, extending their novel use of mid-decade redistricting. And then you could have blue states trying to correct their mistakes and revisiting their district lines as well.

The forthcoming new map in Texas could plunge the country into a constant blizzard of redistricting wars, turning a decennial event into a much more frequent phenomenon. The crucial votes deciding who will control Congress won’t just be cast at the ballot box in November 2026. They’re being held at state houses as we speak.

The Supreme Court did a huge disservice to this country when they ruled political gerrymandering was nonjusticiable in federal court (Rucho v Common Cause 2019). To me, it’s as significant as Citizens United and Presidential Immunity.

💔

Thank you, Gabe. This is exactly what turns voters off of politics. It is voter suppression.

I wrote to my MO Gov. Kehoe and told him, “we see your transparent power grab and it is not a good look.”

He sent a generic reply which included, “Discussions are always being held to ensure that conservative Missouri values are represented in Washington.”

He doesn’t hide that he has no intention of representing all of his constituents.

I replied by reminding him that the majority of MO voters just voted for abortion access in November. That is a Missouri value! And we expect him to respect that and our votes.

Unfortunately, he does not. But we can hold him accountable at the next statewide election.

That is where our power remains.