Target Becomes a Target

Target’s CEO of 11 years, Brian Cornell, announced on August 20 that he will soon be stepping down. That is news that many in the Black community have been waiting to hear.

Across the country, Black Christians are boycotting companies that have pulled back from earlier commitments to the Black community. Chief among them is Target, which announced in January that it would no longer fulfill the racial equity goals it set in 2020.

Target described its change as an effort toward “staying in step with the evolving external landscape.” (This announcement came just four days after President Trump was inaugurated.) Some Black businesses responded by pulling their products from Target’s shelves. Black patrons, for their part, responded by organizing a boycott.

The boycott, known as the Target Fast, boasts more than 200,000 supporters. It is led by Jamal Bryant, the executive pastor at New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, a predominantly Black congregation of roughly 10,000 members in Georgia. The boycott has made four specific demands of Target. Fortune summarizes them: “Invest some of its profits from Black dollars into Black banks, open locations on the campuses of 10 Historically Black Colleges and Universities, complete its 2020 pledge to spend $2 billion on Black small businesses, and reinstate its original DEI hiring and promoting goals.” Target previously pledged to increase the overall share of Black employees by 20 percent and made a broad commitment to increase the number of Black senior leaders.

The name, “Target Fast,” comes from the fact that the boycott was originally to be a Lenten “fast” from shopping at Target, intended to last for the 40 days leading up to Easter. But after Pastor Bryant met with then-CEO Cornell in the final days of Lent and learned that not all of the four demands of the boycotters would be met, the Lenten fast was declared a full boycott. (In that meeting, according to Fortune, Target’s representatives agreed to make good on the financial pledge of $2 billion, but not the boycotters’ other three demands.) It was also at this point that securing Cornell’s resignation became one of the boycott’s express goals.

Some have asked why Target is being singled out, especially given its past support for Black-owned businesses. Boycotters say that the heightened scrutiny is the company’s own doing. Target made clear, long-term commitments to DEI in 2020. In the wake of the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, where Target is headquartered, Brian Cornell famously stated, "That could have been one of my Target team members." Following this, Target announced specific pledges to the Black community, vowing to “hold ourselves accountable to the goals we set” and “remain steadfast in our commitment” while crediting “the support of CEO Brian Cornell.” Just five years later, and still under Cornell’s leadership, Target abandoned its own goals. This is why Target is essentially regarded as the chief offender, though not the only offender. By focusing on Target, the boycotters aim to send a message to all corporations that promises made to the Black community must be kept.

For the Black clergy leading the movement and the thousands of participating Black Christians, the boycott is a facet of discipleship. It is telling that this particular boycott began as a fast. In the Christian tradition, the practice of fasting is a communal act that invites small sacrifice, offered up for love of God and neighbor. That is to say, it’s a lived expression of theology — a corporate, public liturgy, shaping real life and daily habits.

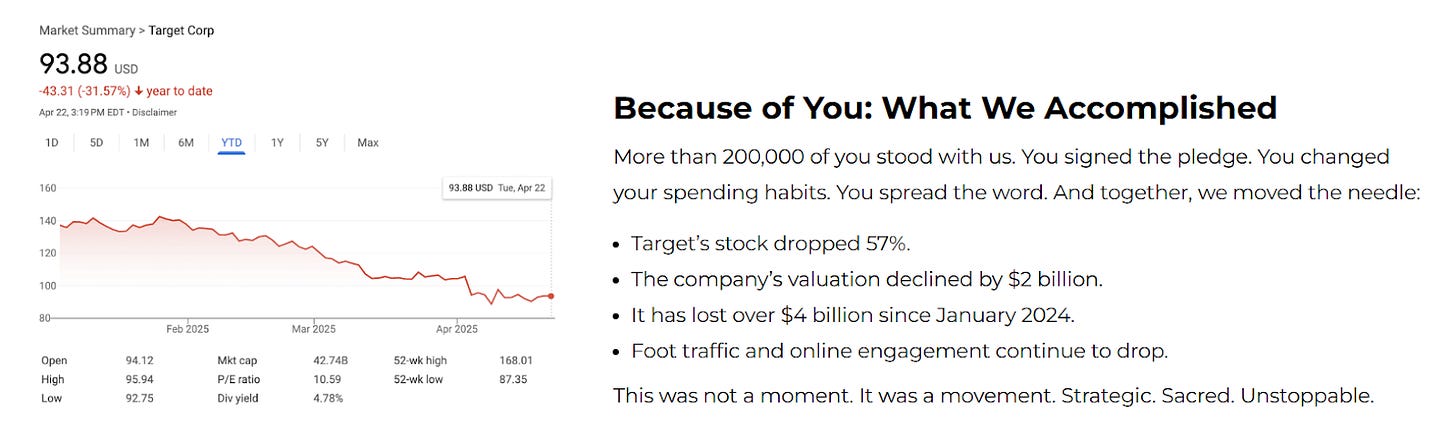

And it seems to be working.

According to data from Placer.ai, Target’s foot traffic has been down throughout 2025 compared with previous years (ranging from -2.2 percent in May to a peak decline of -9.7 percent in February, which is Black History Month).

In an interview with CNN in May, Bryant enumerated the facts of Target’s decline: "They've lost $12 billion in valuation. Their stock tumbled from $145 a share to $93 a share. The CEO's salary was cut by 43 percent… [This shows] what happens when our community mobilizes and stays focused.”

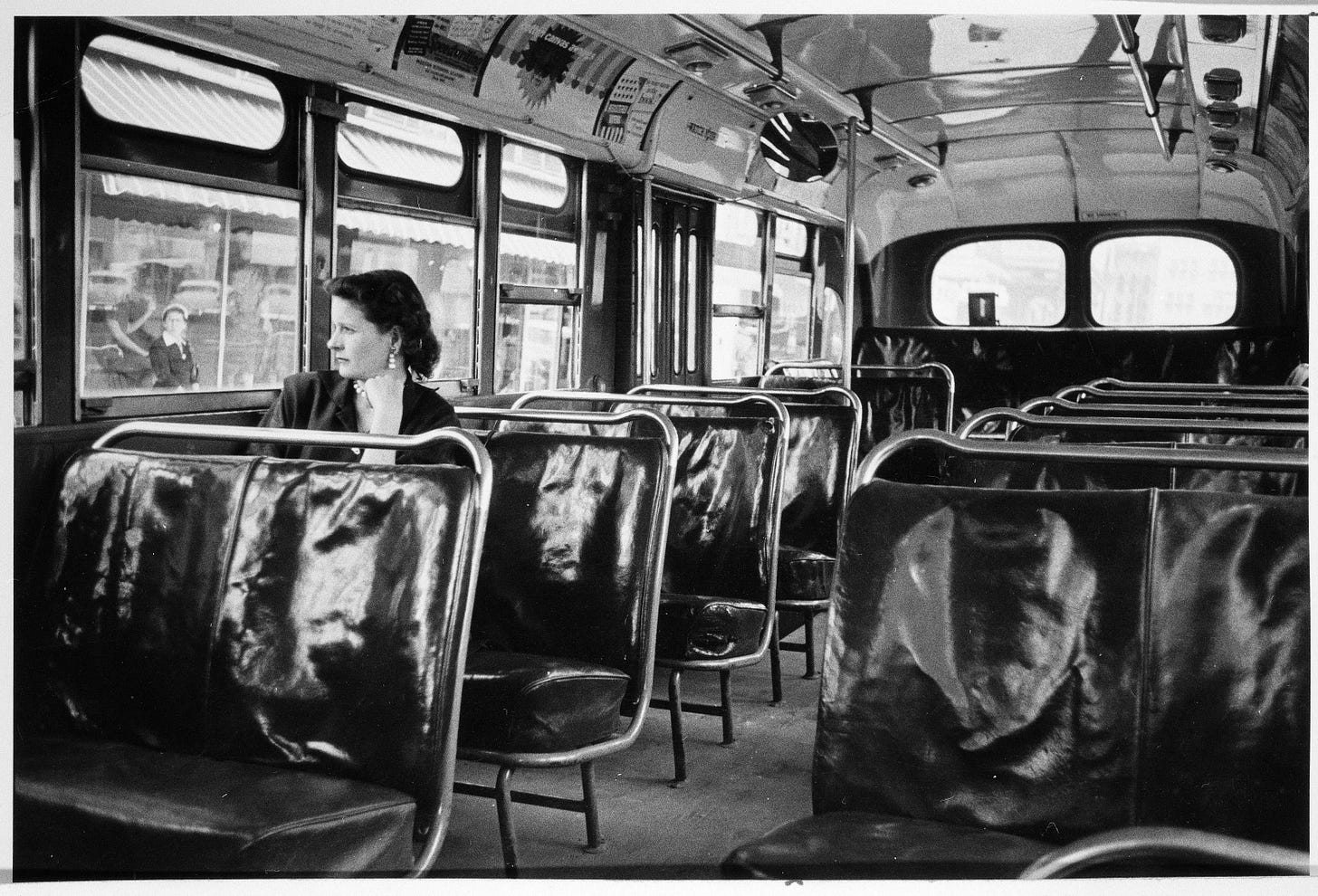

Bryant said this movement is historic, even calling it “the most successful boycott by Black people… since the Montgomery Bus Boycott.” It’s an ambitious claim, but it’s not unfounded.

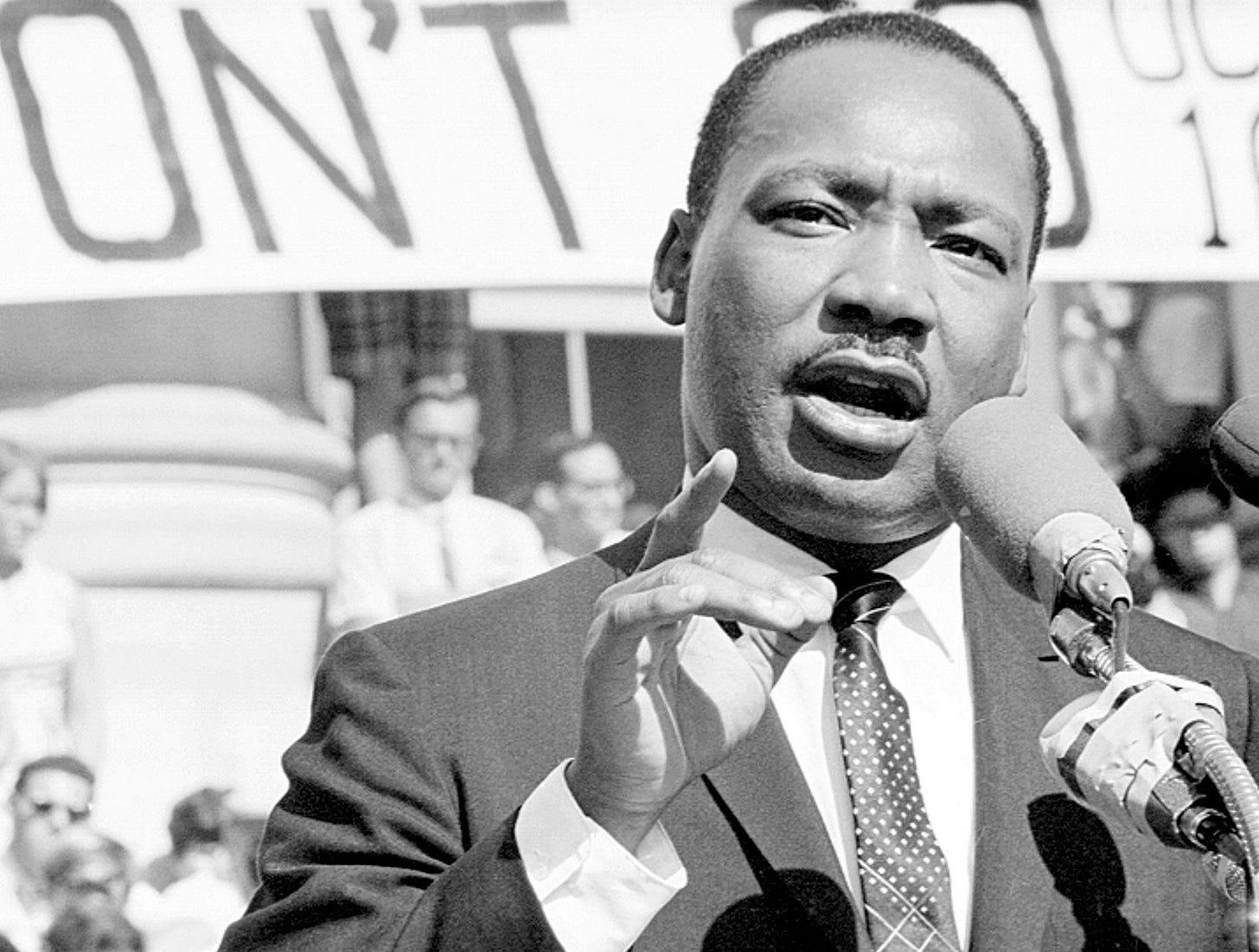

The Montgomery Bus Boycott, after all, began in Black churches. After the arrest of Rosa Parks, local pastors and community leaders in Montgomery, AL, organized a citywide bus boycott. They appointed a 26-year-old reverend to lead it: Martin Luther King Jr. Beginning on December 5, 1955, four days after Parks’s arrest, roughly 40,000 African Americans came together to protest segregated busing in the city of Montgomery. Because carpool efforts were continually sabotaged, many had to commute on foot, which was often dangerous due to the threat of racist violence. The homes of three of the boycott’s prominent leaders were bombed. Still, the boycotters carried on. The campaign lasted 381 days.

In leading the bus boycott, King was strategic. He believed that focused, targeted action — rather than broad outrage — had the power to start a cascade of change. Some thought the boycott’s target was strangely specific. Why just busing, and why only in Montgomery? But by zeroing in on one tangible goal, the movement gained cohesion and momentum. The effort not only succeeded in Montgomery but, along with victory in the lawsuit Browder v. Gayle, which ruled that segregated busing was unconstitutional, helped end bus segregation nationwide. A seemingly small victory in one city in Alabama proved to be a pivotal win for African Americans everywhere. Bryant is following in the tradition of King, seeking to channel widespread discontent into a visible, specific campaign.

Before the boycotts of the Civil Rights Movement, abolitionists organized the Free Produce Movement, refusing to buy goods made with slave labor. Boycotts, in short, are nothing new to the American tradition of racial justice. In the present day, as various expressions of DEI are now curtailed or prohibited, it may once again be the tried and true boycott that carries the work forward.

When asked about fulfilling Target’s DEI commitments back in 2023, Cornell said, “The things we’ve done from a DE&I standpoint, it’s adding value, it’s helping us drive sales… and those are just the right things for our business today.” That last statement is key. It may explain Target’s sudden shift. What was “just the right thing for business” in 2023 was no longer the right thing for business in 2025.

Target does not exist in a vacuum. A series of executive orders related to DEI issued in January 2025 forced all companies nationwide to consider whether they were complying with the new regulations. These new regulations made it so that previous efforts to seek more equitable outcomes are now deemed “illegal discrimination” themselves. (Target’s previous DEI hiring and advancement goals for Black employees, for example, could be considered “illegal discrimination” and at odds with “merit-based opportunity.”) Around this same time, other retailers, such as Walmart and Amazon, also decided to rework or renege on DEI programs and policies that could potentially have led to unwanted investigations. Target’s decision to walk back its commitments to the Black community was likely a calculated response to this same pressure.

While some have been celebrating Cornell’s departure, others have pointed out that it’s little more than an internal reshuffling. Cornell is stepping down as CEO, but he is not actually leaving the company. He will become executive chairman. The incoming CEO is an internal hire: Michael Fiddelke. He is currently the chief operating officer and has been with Target for 22 years.

When Bryant was asked whether he saw the change in leadership as a promising shift, he said, “I think there’s nothing really different about the ideology or their stance on DEI,” and “just moving the COO to the CEO is really stylish, but it has no substance.” Bryant says he hopes Fiddelke will be willing to meet to discuss the boycotters’ four demands.

Remember, though, that those demands include reinstating the prior hiring commitments. Having this demand met may be particularly difficult — or even potentially unlawful, given the new executive orders.

Regardless, the Target Fast isn’t letting up. The sheer ambition of the boycott could be one of the reasons it has garnered such support. It came at exactly the time when individuals’ other avenues for supporting DEI efforts became unavailable. When participating in DEI programs at their schools or workplaces was no longer an option, boycotting has presented individuals with an opportunity. The boycott’s invitation is simple: if you’re looking for a response to the DEI rollbacks — especially in a moment when so many efforts are being stalled or shut down, and there is no practical way to object to these changes — this is something you can do. It’s a way to lend your weight to a focused effort led by the Black church and aimed squarely at advancing DEI.

Organizing is difficult. Attention is fleeting. But when a movement gains real traction, we should pay attention — and, for those who support its aims, join in if we can.

Great explainer. I’m a Minnesotan who spent huge amounts at Target over the years. Have not spent a dollar with them since January. I shifted my spending to smaller business where possible and overall am spending less, and it was far less painful than I expected.

I’m a white Midwesterner in a small town where Target had been my favorite shopping option. This year, I have not stepped foot inside the store and have purchased ZERO from them. I made this decision in solidarity with both the black and LGBTQIA communities 🌈🖤 I did the same thing with Amazon, which was my other go-to shopping. It was much easier than I thought! I have shifted to ways to shop local, got a COSTCO membership ⭐️, order directly from the manufacturers if needed, use Etsy, or do without. It feels good to see a boycott working!! 🎉