Restricted Access

Why “protecting people” is actually just controlling them

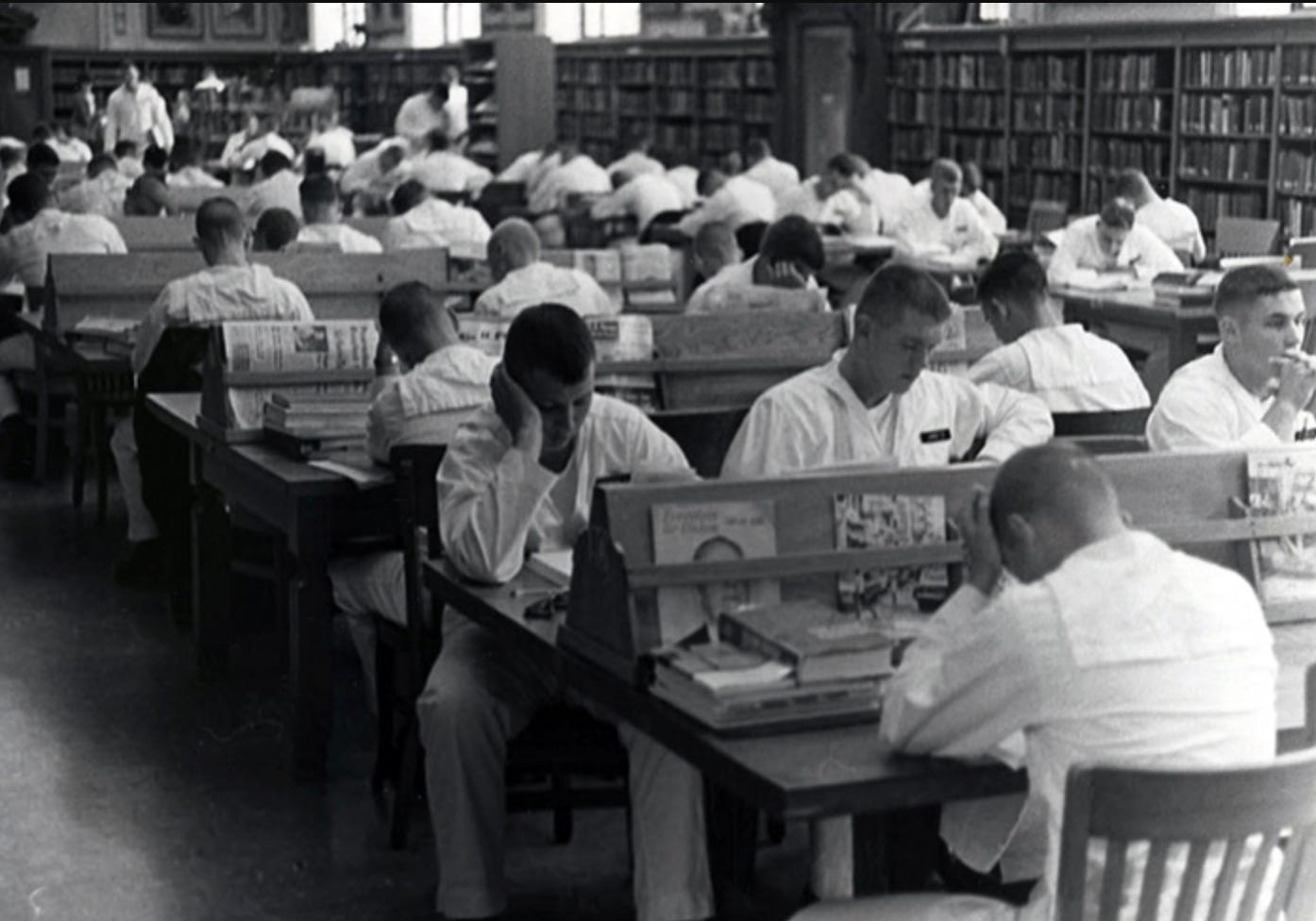

Late-afternoon light fell through the high windows of the library in long, pale rectangles, catching the dust that drifted above the carpet like snow that had forgotten how to land. The building was warm in that particular way libraries are warm — radiators ticking softly, paper holding the heat, the air carrying a faint trace of glue and bindings. Somewhere in the back, a printer woke up and sighed out a page.

A student — old enough to vote, old enough to enlist, old enough to sign their name to an oath — moved down a row of shelves looking for a title he couldn’t quite remember the name of, so he pulled out his laptop, typing the fragments into the catalog.

The results returned right away: title, author, location. And then, beneath it, the small print: “Not in circulation. Restricted access.” The words sat there in the same font as everything else, as though the book had simply been checked out by another student.

He tried again. Different fragments. A different title. Another search, another neat little row of information, another status line that closed like a gate.

The library around him kept breathing. Pages turned. Chairs shifted. Someone laughed softly at a nearby table, the sound swallowed quickly by carpet and stacks. Nothing about the room announced what had just happened.

If the book was checked out, he could wait. If it was missing, the library could replace it. But this was something different entirely: upstream interference.

It means someone has decided that the safest version of him — the most acceptable version of him — is a version who never ran into this sentence, never encountered this argument, never had to wrestle with this story.

And this is the American question hiding inside a line of small print: Who gets to decide what you are allowed to confront?

Americans like to talk about liberty as if it lives only in big, bright places: on podiums and parchment, in speeches and monuments, in the clean romance of founding stories and the excitement of a revolution. But liberty also shows up in the spaces where people go to rendezvous with ideas they didn’t grow up with or didn’t vote for.

A free country does not only protect the right to speak. It protects the right to seek. The right to pick up a book because it is famous, or because it is reviled, or because it is sitting at eye level and your hand reaches before your mind makes a plan.

That is the American bargain: we trade the comfort of control for the liberty of choice. We live among people who will read what we would never read, believe what we would never believe, and say what we wish they wouldn’t say, and we do it because the alternative is a country where someone else decides which thoughts are safe for us.

When we restrict the arteries of information, we train people to treat inquiry as suspicious. We grow a nation of permission seekers rather than a nation of critical thinkers.

And you can hear the reasoning every time it happens. “These are terrible ideas, and people should be protected from them,” those in power say. But the solutions offered are never: better teaching, deeper context, stronger discernment. The solution is always to allow someone at the top to clamp down the artery of information.

But the American version of liberty was never meant to depend on the confidence of the most anxious or controlling person in the room. This is a country that believed ordinary people could be trusted to encounter an idea with which they disagreed and to survive the discomfort. Argue, reject, wrestle, learn? Yes. But still remain free.

A book ban is un-American for this simplest reason: it takes a decision that belongs in the private space that exists between a person and their conscience and turns it into a public act of control. It says: some encounters are not yours to have, and someone who has not earned your trust will be the one to choose on your behalf.

That is how a nation loses liberty without noticing. With a list. With an empty place on a shelf. With an email. With a pull of funding if compliance is not ensured.

It takes the form of responsible and reasonable people saying, “We must protect the children. We need to keep politics out of the classroom. We need to stop indoctrination. We need to keep certain information from being shoved down anyone’s throat.”

The instinct to treat access as a privilege is older than the internet and older than school boards. In the 19th century, the choke point was the mail. If you could control what traveled, you could control what arrived. That was the logic behind federal efforts to detain certain publications.

The Supreme Court’s modern First Amendment doctrine developed, in part, as a rebuttal to that logic. Over and over, the Court has recognized that free speech is not only about protecting the speaker, it also protects the audience — the citizen who wants to read, hear, and learn. In Stanley v. Georgia, the Court said it was “well established” that the Constitution protects the right to receive information and ideas, even when those ideas are unpopular or low-status.

That “right to receive” principle is also why school libraries became constitutional battlegrounds. In Board of Education v. Pico, the Court held that a school board cannot remove books from a school library simply because it dislikes the ideas inside them — because a library, unlike a required curriculum, is the place in a school designed for voluntary inquiry. The case is messy in its votes, but the underlying warning is clear: when officials purge shelves to enforce ideological conformity, they are not “curating.”

In December 2025, the Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal in the Llano County, Texas, case after the Fifth Circuit allowed local officials to remove certain books from public libraries. The Fifth Circuit rejected the patrons’ claim that they had a First Amendment right to receive information in that setting. The Supreme Court’s decision not to take the case lets that Fifth Circuit ruling stand in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, without settling the question nationally.

And that is precisely why these arguments matter. It is not the role of the government to pre-decide which stories its citizens are fit to meet. In fact, the First Amendment makes the opposite wager.

A library is not a museum of acceptable ideas. It is a civic promise made in wood and brick and paper and databases: you do not have to be rich to learn, you do not have to be powerful to explore, you do not have to belong to the right kind of family to encounter the entirety of human knowledge.

Book banning breaks that promise. A young person learns that there are some ideas they aren’t fit to grapple with. Parents learn that someone else’s moral panic must become their household’s policy. A librarian learns that their work — the quiet work of stewarding a public good — can be recast as suspicious. A teacher learns to hesitate before placing a novel on a syllabus, before offering a memoir as an option, before recommending a title in the way teachers have always done.

Sometimes liberty doesn’t disappear in the whistle of bombs. It disappears in the status displayed in the library catalog.

It’s simpler and faster to control the supply of information than to raise citizens who can think for themselves. But a free country must not require its citizens to live inside someone else’s level of comfort.

Liberty is not the promise you will never encounter information that offends you. It’s a promise that you are trusted to encounter it anyway, and remain free enough to decide what you will do with it.

Most thoughtful, powerful, succinct commentary I’ve read on banning ideas. This should be posted in every library and school. Thank you for the intelligent insights. Keep them coming!

As a public school teacher, thank you for this excellent commentary. As a science teacher, I hear many “ideas” from students that they believe are “truths”. Not having access to books or periodicals that open our eyes and minds is dangerous. I am thankful for your voice during this time in our country.