Pardoning Fauci?

What might Biden's final weeks in office hold?

Last week, US District Court Judge Mark C. Scarsi wrote, "The Constitution provides the President with broad authority to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, but nowhere does the Constitution give the President the authority to rewrite history.”

Scarsi’s statements came in the wake of President Biden’s pardon of his son Hunter. Hunter’s lawyer formally asked the Scarsi to dismiss the charges against him, charges that the President says were politically motivated and not in keeping with the kind of treatment other defendants would receive.

Biden cites the fact that his plea deals were repudiated by judges, and asks the American people to “understand why a father and a President would come to this decision.”

Scarsi, who presided over Hunter Biden’s California tax fraud case, says that Biden’s characterization of events “stand in tension with the case record.”

And of course, there’s the elephant in the room: Biden had already promised, repeatedly, not to pardon his son. Conservative news outlets have had a field day with that fact that Biden pledged to do one thing, and has now changed his mind and is doing another.

When pressed, White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said that circumstances changed, and that caused Biden to rethink his decision. “Republicans said they weren’t going to let up,” she said. “Recently announced Trump appointees for law enforcement have said on the campaign that they were out for retribution, and I think we should believe their words, right? We should believe what they say.”

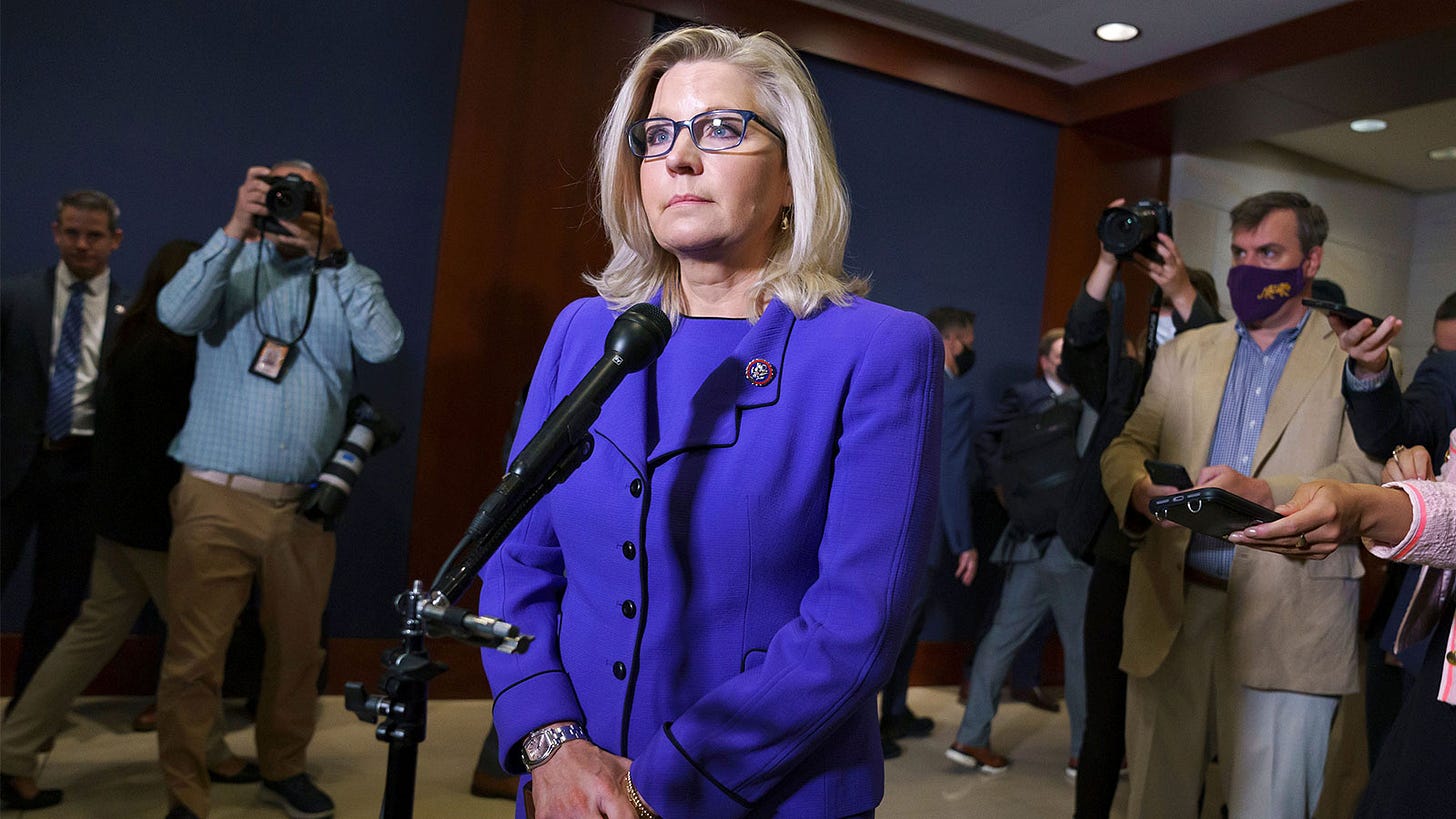

With six weeks left in his presidency, rumors have begun swirling as Biden staff members have reportedly been spearheading conversations about issuing other pardons. Not for family members, but for people like Liz Cheney and Anthony Fauci, people that Biden fears may become targets of the incoming administration.

And that begs the question: can he do that? Can presidents just wave a proverbial pardoning wand and protect certain people from future trouble?

To answer that, let’s go back to where the power to pardon even comes from. It can be found in Article II of the Constitution, which reads that presidents have the power to “grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment.”

The idea that a ruler should be allowed to pardon originated more than 1500 years ago under British law, and it was Alexander Hamilton who first floated the idea that presidents should be granted this right. The framers debated whether pardons should have to be approved by Congress or a judge, and decided against it. They felt that the people making the laws and judging the laws should not be the same as the one granting the pardons.

No president pardoned more people than FDR: he clocks in at 2,819 pardons, many of them people who had been convicted under prohibition laws before prohibition was done away with. So far, Biden has issued only 26 pardons, but that number is likely to increase dramatically in the coming weeks. Trump pardoned a total of 143 people during his four years in office, Obama 212 in his eight, and George W. Bush pardoned 189 people during his two terms.

The Supreme Court has affirmed that a president’s pardoning power is nearly unlimited. In Ex parte Garland, the Court said that the power to pardon “extends to every offense known to [federal] law, and may be exercised at any time after its commission, either before legal proceedings are taken or during their pendency, or after conviction and judgment.”

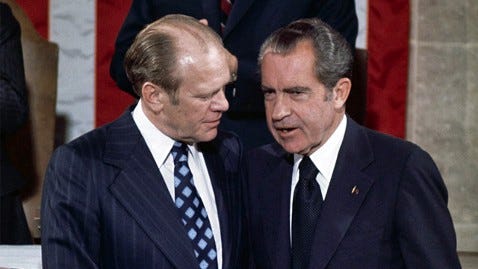

This helps explain how Gerald Ford was able to issue a pardon for Richard Nixon. Nixon had been accused of crimes, yes, but not formally charged with them. Ex parte Garland was decided in 1866, and the precedent has stood since then.

There’s always the chance that a pardon could be challenged in court and that the Supreme Court could choose to abandon their 158 year old precedent, but I think that’s unlikely. If anything, the sitting Court has been increasing the power of the president, not diminishing it.

In another case, Burdick v United States, the Court held that accepting a pardon brings with it “an imputation of guilt and acceptance of a confession of it,” meaning that someone who accepts a pardon is legally admitting they are guilty, whether they want to say it or not. Because they are admitting guilt, the Court found that someone cannot be forced to accept a pardon.

So does this mean that if Biden pardons, say, Liz Cheney, that she would be untouchable, and that future administrations could not prosecute her? A few things to consider here:

1. A presidential pardon only protects you from federal prosecution, not state. So it’s possible that a state could decide to prosecute. You can see this in the prosecutions of Trump: there was a state case brought in Georgia, and another federal case brought by Jack Smith.

2. A pardon is not a get out of jail free card, that allows you to get away with any and all crimes in the past or the future. If Biden were to pardon someone like Cheney for her activities surrounding January 6th in an effort to protect her from prosecution, that doesn’t mean she could get into a drunk driving accident and not be prosecuted. You cannot pardon against future acts.

But there is another factor here, which is a concept brought up in the case In re Neagle. That case, also from the 1800s, found that federal officials cannot be prosecuted at the state level for actions undertaken while acting on behalf of the federal government.

Say a state wanted to prosecute Anthony Fauci for something that happened during the Covid pandemic. His lawyers would likely argue the legal precedent that people “acting under the authority of the United States” cannot be subjected to state prosecutions.

3. Pardons don’t protect you from civil lawsuits. Even if someone like Fauci or Cheney were to make a claim of qualified immunity, just having to defend themselves against potential lawsuits could lead to hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal bills. Pardons also don’t protect you from IRS audits or state investigations into your finances.

Presidents can pardon preemptively, meaning before someone is charged with a crime, but not before the crime was committed. And while the president’s pardoning power is extremely broad, the limits don’t mean that someone won’t be subjected to life-changing investigations, civil suits, and allegations.

Biden’s time in office is short. And we’ll soon see what happens.

Thanks, Sharon. I think we need to be talking more about the immense concern that Trump is even considering going after people who did not commit crimes.

What crimes did Fauci and Cheney commit?