Out with the Old?

Is this a...gerontocracy?

A new Congress was just seated, and there will be a change in administration soon. Now seems to be an appropriate time to reflect on one of 2024’s dominant themes: generational change — and when it will finally take place in American politics.

Of course, this theme was felt most notably in 2024 on the presidential level: per the Wall Street Journal, President Joe Biden — who turned 82 last month — has had “good days” and “bad days” at least since spring 2021. “If the president was having an off day, meetings could be scrapped altogether,” according to the Journal. “Former administration officials said it often didn’t seem like Biden had his finger on the pulse,” the report also alleged.

It was Biden’s advanced age (seen most viscerally on the debate stage) that ultimately led his fellow Democrats to push him out of the presidential race, which was won by 78-year-old Donald Trump. By the time Trump leaves office in 2029, he will be 82 years and seven months old, taking over Biden’s record as the oldest president in U.S. history.

On the other side of Pennsylvania Avenue, things aren’t much different: the 118th Congress, was the third-oldest ever in history. None of America’s peer countries have legislators as old, leading some to label the U.S. a “gerontocracy”: a government by old people.

This dynamic has been unfortunately reflected by a string of painful examples in the final weeks of the year. Earlier this month, outgoing Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) — who are both still serving in Congress as rank-and-file members, at ages 82 and 84, respectively — were each injured in separate on-the-job accidents.

McConnell sprained his wrist and cut his face after falling at the Capitol; Pelosi fractured her hip after falling down the stairs while on an official trip to Luxembourg.

Then, last week, the Dallas Express — an independent news outlet run by a Republican operative — reported that 81-year-old Rep. Kay Granger (R-TX), who officially left office on Jan 3 – had been living in a memory care facility. Granger’s son denied the report to the Dallas Morning News, saying his mother was living at a senior living center, not at the memory care facility included on the same property. But he did confirm that Granger, a sitting congresswoman, has been “having some dementia issues.”

Granger unexpectedly stepped down as chair of the powerful House Appropriations Committee in April; she hasn’t voted since July, even while continuing to serve (at least in theory) as the representative of Texas’ 12th congressional district.

The revelations about Granger have sparked fresh conversations about aging on Capitol Hill. “We need to do some norm changing at a minimum,” Rep. Jared Huffman (D-CA) told Politico. “It should really be unacceptable for members to be completely missing from communications with the public and with their own colleagues for months at a time.”

“Kay Granger's long absence reveals the problem with a Congress that rewards seniority & relationships more than merit & ideas,” Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA) wrote on X. “We have a sclerotic gerontocracy.”

Huffman and Khanna are both members of the House Democratic Caucus, which has been having its own roiling debates about age and generational leadership in the last few weeks.

Traditionally, House Democrats have been the the greatest bastion of seniority rule in Congress: while Republicans impose term limits on their committee leadership, Democrats typically allow the members who have served in Washington the longest to wield their committee gavels (or, when the party is in the minority, to serve as ranking members).

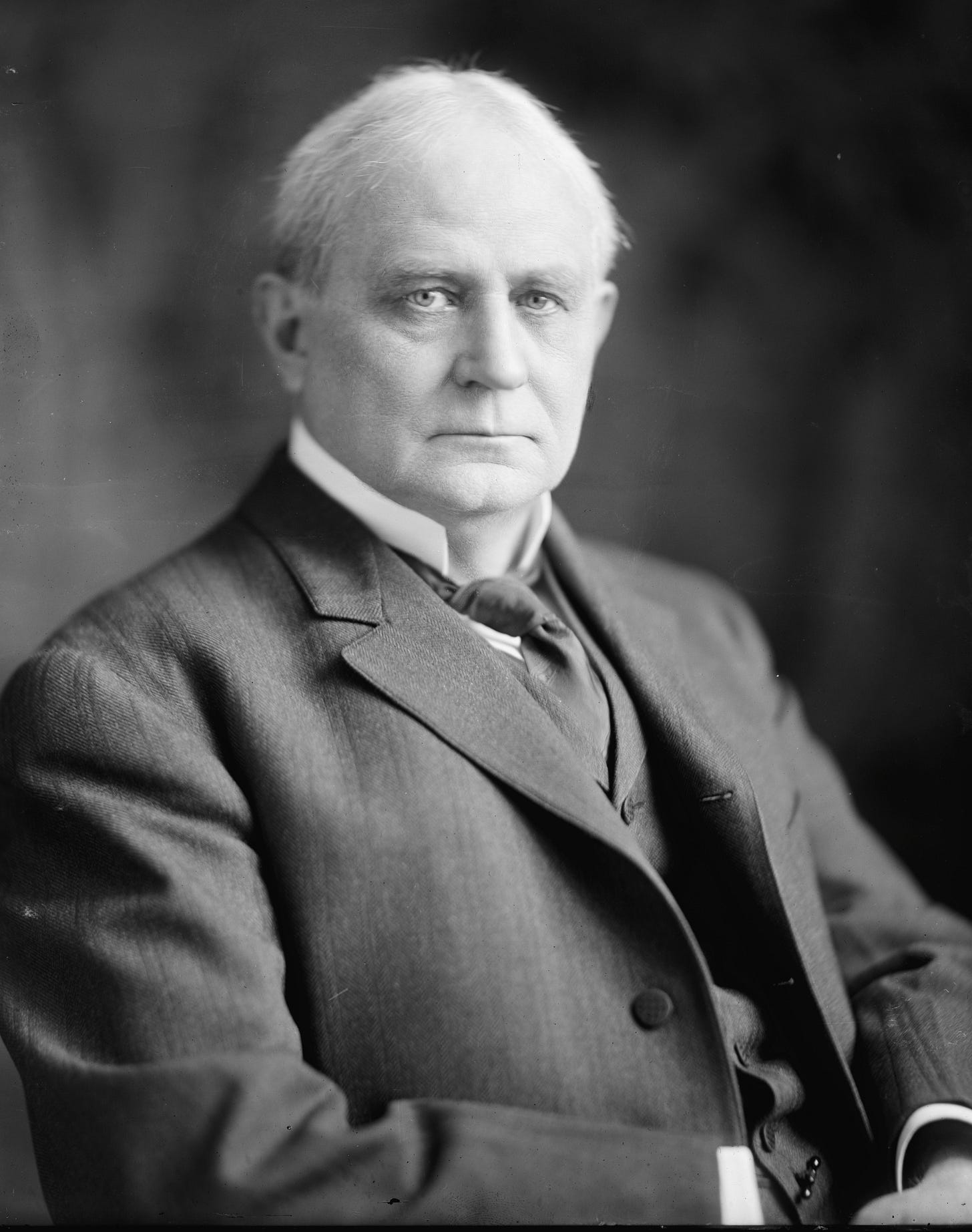

That expectation dates back at least to the days of House Speaker Champ Clark, a Missouri Democrat who ruled over the House in the 1910s. In total, Clark spent close to three decades in Congress. Here’s how he defended the seniority system in his 1920 memoir, My Quarter Century in American Politics:

“No sane man would for one moment think of making a graduate from West Point a full general, or one from Annapolis an admiral, or one from any university or college chief of a great newspaper, magazine or business house,” Clark pointed out. “A priest or a preacher who has just taken orders is not immediately made a bishop, archbishop or cardinal. In every walk of life ‘men must tarry at Jericho till their beards are grown.’”

Perhaps most famously, the Democratic seniority system reared its head during the 1950s and 60s, as it allowed longtime Southern lawmakers to vault to the top of key committees, where they were able to bottle up key progressive legislation for years. Virginia’s Howard Smith served in Congress for 36 years; as chair of the House Rules Committee, he was able to delay passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Wilbur Mills of Arkansas, a congressman for 38 years, used his perch as chair of the Ways and Means Committee to stymie the creation of Medicare.

But the House Democrats’ longtime deference to seniority crumbled earlier this month, as three committee ranking members were forced to surrender their posts amid challenges from younger members.

Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D-AZ), 76, stepped aside as the top Democrat on the House Natural Resources Committee after Huffman, 60, announced a challenge against him. Rep. Jerry Nadler (D-NY), 77, gave up his leadership of the House Judiciary Committee after Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD), 61, ran against him.

After the abdications, both Huffman and Raskin were elected to their respective posts for the next Congress. “It’s like the fountain of youth, we found it!” Huffman joked, poking fun at an institution where electing a 60-year-old is considered groundbreaking generational change. (Baby steps, Congress. Baby steps.)

The third leadership change wasn’t as voluntary: Rep. David Scott (D-GA), 79, sought another term as ranking member of the House Agriculture Committee. But the full caucus opted to elevate Rep. Angie Craig (D-MN), 52, a rare example of the party ousting an aging committee chief against their will.

Shortly after, Scott — who has battled with health challenges for years — was being pushed in a wheelchair at the Capitol when he upbraided a journalist for attempting to photograph him. “Who gave you the right to take my picture, a**hole?” he yelled, according to a Punchbowl News reporter. (Journalists have long been free to photograph lawmakers at the Capitol.) Scott’s outburst caused yet another round of conversations about congressional gerontocracy.

In another Democratic committee battle, however, more typical patterns of seniority won out. To succeed Raskin as ranking member on the House Oversight Committee — a post he vacated to succeed Nadler on Judiciary — Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), 35, ran against Rep. Gerry Connolly (D-VA), 74.

Ocasio-Cortez is one of the House Democratic Caucus’ youngest members; Connolly has served in Washington for twice as long as her. Despite some concerns about his health (the Virginian has esophagus cancer), Connolly triumphed against AOC, with 131 members of the caucus voting for the lawmaker next in line, while 84 voted for the firebrand upstart.

In some ways, this push-and-pull is nothing new. The senior Southerners flexing their clout in the ’50s and ’60s led to a reform push in the 1970s, when the House Democratic Caucus — in a move similar to the clashes this month — ousted a trio of committee leaders (two Texans and a Louisianan) in violation of the seniority system. Five other aging chairmen, recognizing that the times were turning against them, either retired from Congress or gave up their gavels voluntarily.

We appear to have arrived at a similar moment of transition, brought on by similar frustrations.

After the new revelations about Granger, the congressional press corps is likely to be watching aging lawmakers even more closely; after the revelations about Biden, White House reporters can be expected to ask more questions about presidential health and fitness. Democrats, too, were clearly scarred by the Biden experience, as seen in their unusual willingness to push aside veteran colleagues like Scott, Nadler, and Grijalva.

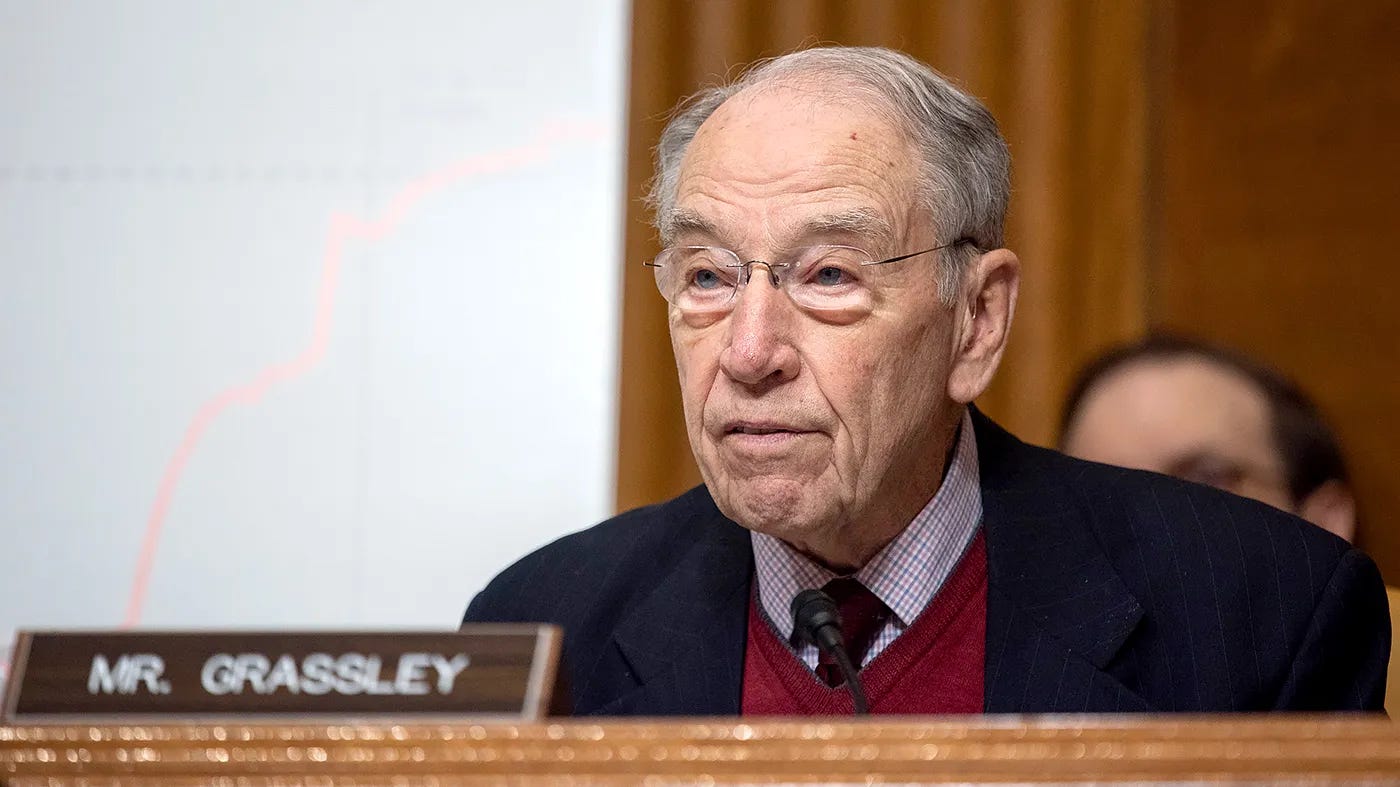

Aging leaders are not gone: President-elect Donald Trump, again, is 78; Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) — at 91! — is the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, placing him three heartbeats away from the presidency. (This job is a largely ceremonial position, generally given to the longest-serving member of the Senate’s majority party. The job comes with few real responsibilities… but it is third in the presidential line of succession. Starting next month, if the President, Vice president, and Speaker of the House all pass away, the nonagenarian Grassley would become commander-in-chief.)

Still, in other places: change is clearly afoot. Many of Trump’s nominees are strikingly young, including 27-year-old White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt, 40-year-old UN Ambassador nominee Elise Stefanik, and 44-year-old Defense Secretary nominee Pete Hegseth.

The early frontrunner for the 2028 Republican presidential nomination, Vice President-elect JD Vance, is only 40, the second-youngest VP in U.S. history. (Fun fact: being a young VP is how Teddy Roosevelt got to be the youngest president – he was 42 when McKinley was assassinated.

With Democrats likely to elevate a younger choice as well, 2028 is poised to be the first presidential race since 2012 not to feature at least one candidate in their 70s. It could also be the first since 2000 — nearly three decades earlier — to feature two candidates in their 50s or even younger.

The gerontocracy may not be completely gone from Washington — but after 2024 was marked by several high-profile examples of aging leadership, new pockets of youth are set to assert themselves in 2025 and the years ahead.

Find more Gabe Fleisher at Wake Up To Politics .

The Constitution requires presidents be at least 35, an indication that we have long understood that lacking brain development and knowledge are disqualifying factors on the front end of the age spectrum. We should apply this logic to the other end as well.

Even though there are plenty of folks who live healthy lives longer than the statistical average (I know a woman who is 100 that is more mentally sharp than me some days), we should pick an age where the stats tend to drop off for health indicators, even if it feels a little bit arbitrary. I believe that no one should begin a term after 69, meaning the oldest serving officials would complete their terms at 71 for House members (2-year terms), 73 for presidents (4-year terms), and 75 for senators (6-year terms). For Supreme Court justices, who currently serve life terms, mandatory retirement at 75 would ensure similar protection against decline.

This wouldn't silence elder wisdom; experienced statespeople could serve as advisors, mentors, and public voices without holding the daily responsibilities of office, or leaving constituents voiceless during secret health issues. Just as importantly, it would create space for fresh perspectives in a system that currently suffocates young talent.

Leadership transitions should not be driven by crisis, yet the current system of letting leaders subjectively evaluate their own fitness creates exactly that. The cases in this article - from Granger's memory care to Biden's 'good days and bad days' - show the cost of our reluctance to set clear guardrails. My former Senator Dianne Feinstein didn't get a mention, but she was another recent example of someone who was clearly incapable of her job, surrounded by people lying to the public about her reality.

These situations force us to have icky conversations about folks in wheelchairs screaming angrily about having their photo taken - a spectacle that serves no one. Age limits would actually make politics more respectful to seniors, sparing them from public scrutiny of their decline while preserving their legacy of service.

I would love to see older senators and representatives mentor and cheer on the younger generation to rise up and serve in politics. It seems that they find it difficult to release some of their “power.”Maybe that means term limits should be considered also.

Since we have peaceful transfer of power, shouldn’t we be allowing younger people to fill these positions so they have time to learn before getting on the more prestigious committees?