Memorial Day Was Born From Grief — and Immigration

We just don’t talk about it that way.

Together with:

He was only 17, but he knew enough to wait until nightfall. With the lantern light of Boston Harbor glimmering in the distance, a young Joseph Pulitzer slipped overboard, the cold waters of the Atlantic swirling around him. He swam hard, pulling for shore, determined to make landfall before the recruiters noticed he was gone.

Pulitzer staggered, his sea legs wobbly beneath him, before making the decision to leave Boston immediately and head for New York. He spoke barely a word of English. The year was 1864, and like many immigrants who graced American shores during the Civil war, Pulitzer had been offered a bounty — money promised to foreign recruits in exchange for joining the Union Army.

Pulitzer would change the course of history. But before that, he was just one of hundreds of thousands of immigrants who fought, and often died, in the Civil War.

Immigrants in the the Union Army: fighting for a new home

Pulitzer’s story might sound wild, but it wasn’t unique. During the Civil War, roughly one-quarter of the more than two million soldiers in the Union Army were immigrants, and even more were the children of immigrants. All told, more than 40% of Union soldiers were either foreign-born or had a foreign-born parent.

Many had just arrived in the US — from Ireland and Germany (the largest groups, at roughly 150,000 to 200,000 each), as well as Hungary, Italy, and other parts of Europe. Most were poor, spoke little or no English, and had come in search of a better life.

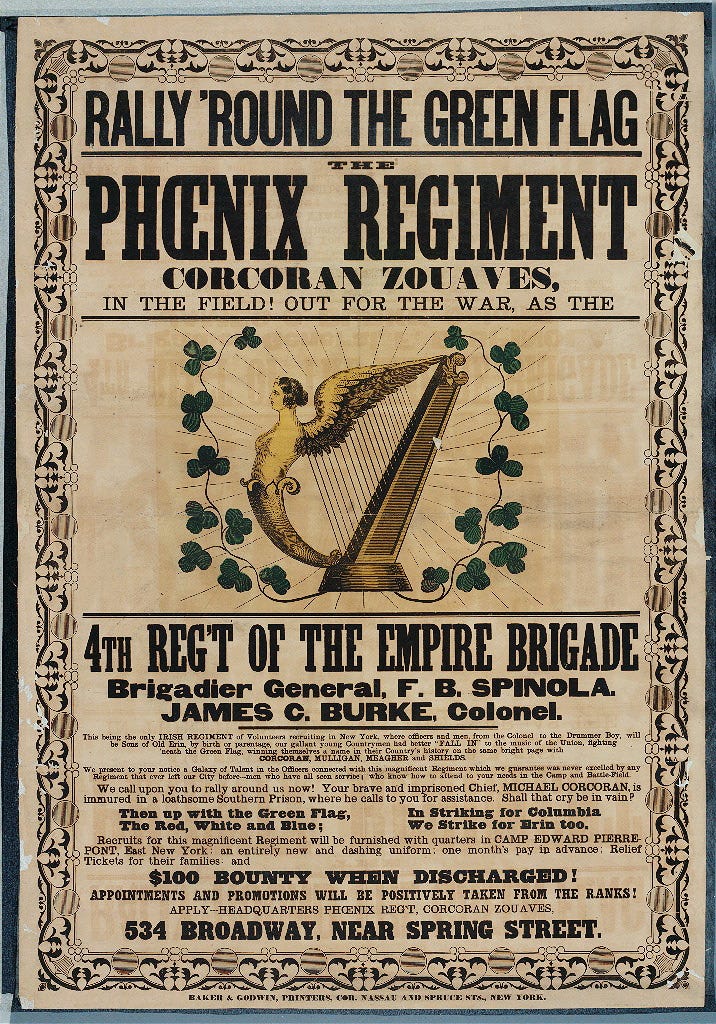

The Union needed soldiers, and they were willing to pay. The government — and sometimes individual towns or states — offered cash bounties to foreigners who enlisted. At first, these payments were just a few dollars. But as the war dragged on and enthusiasm waned, the bounties soared — to hundreds, even up to $1,500 (about $31,000 today). That kind of money could change a new immigrant’s life.

But paying people to enlist didn’t create a big enough army. So in 1863 the Union began conscripting men into military service. If you were drafted, you could pay a $300 fee to the government or hire someone to take your place — an option that only the wealthy could afford. Often, the “replacements” for the conscripted wealthy men were poor immigrants like Pulitzer.

In fact, when the draft began, a group of mostly Irish immigrants led a violent anti-draft riot in New York City that lasted four days and killed more than 100 people. The protest wasn’t just about war — it was about inequality. The rich could buy their way while the poor, especially immigrants, were being sent to die.

Recruitment agents took full advantage of the financial opportunity that the bounties offered. They gathered in immigrant neighborhoods or even traveled overseas — like they did when they found Pulitzer in Germany — looking for men willing to fight. To drum up excitement, they sometimes threw parades, gave patriotic speeches, and waved flags. The promise of adventure and quick cash was hard to resist for many.

The recruits didn’t always get the payout they expected. Sometimes these agents were honest. Too often, they weren’t. They’d take a big cut of the bounty and leave recruits with almost nothing. Pulitzer refused to let that happen to him — which is why he leapt into Boston Harbor to claim his bounty directly, bypassing the recruiting station in Boston and leaving town before anyone from the ship recognized him.

From OneSkin:

OneSkin has always been pro-healthy aging. For Memorial Day, they’re offering up to $117 in travel size gifts with your order. Choose from their most trusted treatments, including PREP daily cleanser, OS-01 EYE, OS-01 FACE, and OS-01 BODY—all hydrating, gentle, and clinically backed. Consider it a smart skin policy made for longevity.

Get 15% off your first purchase with code PREAMBLE at oneskin.co/PREAMBLE.

Despite corruption and danger, many immigrant soldiers became heroes. The Union didn’t just welcome them — it depended on them. Entire units were formed around shared language or national identity: there were German regiments that gave orders in German, Hungarian units, Irish brigades, and Italian companies. These groups brought their cultures and languages into the war effort — and often suffered heavy losses.

One famous group, the Irish Brigade, fought in some of the bloodiest battles of the war. Their bravery became legendary, but they paid a high price: thousands died. In fact, the first soldier killed in the Civil War was also an immigrant — Private Daniel Hough, an Irishman who died in an accidental explosion at Fort Sumter, SC, in April 1861.

No one knows exactly how many immigrant soldiers gave their lives and died during the war. The military didn’t track the country of birth very carefully. But we know the number is likely in the tens or even hundreds of thousands — a reminder that many who fought and died for the US weren’t even citizens yet.

From Civil War to Memorial Day’s beginnings

That brings us to Memorial Day.

The Civil War didn’t just threaten to rip the Union asunder. It tore apart families, as they grieved the deaths of more than 700,000 people. (By contrast, around 400,000 Americans died in WWII.) Joseph Pulitzer was there in April 1865 when General Lee surrendered in Appomattox. April is lovely in Virginia — the sun is bright, but not too hot. Flowers erupt from the ground, ejected from their winter slumber beneath the soil. And soon, people began to gather these flowers to adorn the graves of their loved ones.

It happened organically at first: people marking the end of the war by decorating the resting places of fallen soldiers. But by 1868, it became official, when James Garfield (a congressman who would later become president) spoke to an assembled crowd of 5,000 on the first official Decoration Day.

“If silence is ever golden,” he said, “it must be here beside the graves of fifteen thousand men, whose lives were more significant than speech, and whose death was a poem, the music of which can never be sung.”

By 1873, New York was the first state to officially declare May 30 as a day of remembrance. By 1890, all of the other states in the Union had followed suit. Over the following decades, the US government and private cemeteries around the country installed Memorial Day Order plaques to commemorate the dead.

After the dust settled from WWII, there was a renewed interest in formalizing Memorial Day as a national holiday — in 1950, Congress approved a joint resolution that asked the president to “issue a proclamation calling upon the people of the United States to observe each Memorial Day as a day of prayer for permanent peace and designating a period during each such day when the people of the United States might unite in such supplication."

During the Lyndon Johnson presidency, Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, moving some federal holidays, like Memorial Day, to a designated Monday as opposed to a fixed date. Memorial Day used to be celebrated on May 30, but the act changed it to the last Monday in May.

What about Joseph Pulitzer?

After his service as an immigrant in the army, Pulitzer became a famous newspaperman, purchasing the failing New York World and turning it into the most profitable newspaper in the country at the time. In its editorial pages, he dedicated space to fighting for ordinary people, challenging corruption, and championing free speech. His name is still known today because of the Pulitzer Prizes, which honor the best work in journalism, literature, and music.

But he began his time in America as a teenage immigrant who owned only a white handkerchief, which he sold to try and avoid starvation. His story, like the stories of the thousands of immigrants and Americans we memorialize this year, reminds us that America has always depended on people from other places — not just to build a nation, but to defend it.

Thank you, Sharon. This article was posted earlier and I commented on it, then I got a reply that misinterpreted what I was saying. That might have been my fault for not being clear enough.

I was in the middle of replying to that reply to clarify, starting to panic that people would misunderstand what I was saying and think I was critiquing the article and people in the military (the complete OPPOSITE, I love this article and have a deep respect for people who serve!), but then the article disappeared. I wonder if people still might have misunderstood my perspective.

My original comment was critiquing a traditional "Hollywood" narrative about service (the narrative that people often make the decision to serve out of pure principle and love of country, divorced from their economic circumstances). I believe that the recruitment system often exploits people's economic vulnerabilities. I was welcoming how this historical analysis shows our history of exploiting poor people and immigrants to serve in the military goes way back. So here's my original comment, edited for clarity.

The reality, as you point out, is that it's often reluctant young people without many other options trying to figure out how to start their adult lives. That doesn't make their sacrifice any less meaningful - if anything, it makes it more profound because they gave their lives even when the system they were protecting didn't respect them back. Even if they had to swim Boston Harbor to get what was promised to them.

This brings back so many memories of my own high school classmates, including two of my foster brothers, who made the decision to enlist. Neither of them seemingly did it out of burning love for America. My brothers specifically hated the government after everything they'd seen in the foster care system before joining our family. Their father was an undocumented Mexican immigrant who was murdered by a stranger before they were old enough to know who he was. Their mother wasn't fit to care for them due to drug addiction. They shuffled from family to family until they ended up with us right on the cusp of becoming teenagers. But they didn't think college was for them, and the school counselors would basically nudge them toward the military with the argument "what else are you going to do?" Military recruiters would show up on campus like they had the answer for teenage boredom, more than any realistic descriptions of what the choice to serve would look like.

The older of the two, who was my age, seemed to embrace the forced discipline of military service, which was ironic given how much he'd fought against any authority figures during our childhood. He would even point that irony out on his home visits, but the difference for him was that he was allowed to carry a gun when he listened to these guys. For a few years he'd come home on leave, full of stories about the good times he was having, but gradually the visits became less frequent and the contact dropped off. When he did show up, it would be unplanned. He’d throw his drink and duck under the table when someone popped a cork. Fireworks made him hate the Fourth of July. He'd wake up screaming from nightmares. It was clear he was dealing with serious PTSD, but he didn't want anyone to mention PTSD around him. All I know now is that he was dishonorably discharged for some reason, moved to Washington state, got married, and posts online almost exclusively about his cat who seems to mean more to him than anything else in the world. My attempts to reach out usually get a "hey bud how's it going" and then silence.

My other foster brother enlisted after literally running away from our house in the middle of the night. He'd been fighting with my parents who told him that on his eighteenth birthday he needed to get a part-time job in town. He ended up punching all the picture frames in the house, leaving smears of blood down the stairs and out the front door. He finished high school living in his friend's basement. That was his state of mind when he decided to join the military. But what he told me later, laughing over a beer at the bar where he now works, was that a few weeks into basic training he lied and said he was gay so they would kick him out. I had just recently come out as gay myself, and we both cracked up about the full-circle moment. He's married now (to a woman), works at a restaurant, and seems to be doing alright.

I realize my brothers' stories aren't typical, but they mirror what I saw with other kids from my graduating class who enlisted in 2003, who immediately got shuffled off to the other side of the world. They weren't the ones volunteering their time after school to help their communities. They were more likely to be into violent video games, blasting country music with lyrics about America putting “a boot up your ass" from their elevated pickup trucks, generally not the friendliest bunch. That's not to say everyone who enlists fits that description, but it was definitely a pattern I noticed. It's more of an observation that our military recruitment system relies heavily on the vulnerabilities of people who don't have much economic power to fill their ranks.

When Memorial Day comes around, people tend to honor fallen soldiers with a stereotypical caricature of who they were and why they served, giving empty platitudes before enjoying a three-day weekend. I really appreciate you telling this history that presents the decision to serve as what it often actually is: not much of a decision at all.

Thank you Sharon for highlighting that our nation of immigrants has always relied on immigrants to build and defend this country. America was built on the backs, and of the blood, of its immigrants - both documented and undocumented. I will always think of my grandfather on Memorial Day and acknowledge him and all the other soldiers who gave their lives in service to our nation. However, this is also a sad reminder that our country has always provided a get-out-of-service-free card to the wealthy, while exploiting America's poorest and most vulnerable. :(