Joy as Resistance

It's okay to feel happiness when the world is on fire

By Isla Flaherty

In a world where headlines are often heartbreaks packaged for immediate consumption, where images of humanitarian crises in Gaza, families ripped apart at immigration hearings, and global conflicts scroll past without pause, our feeds rarely let us catch our breath. But for a moment, everything seemed to change. Taylor Swift announced her latest album, The Life of a Showgirl, and social media exploded. Fans spotted Easter eggs, livestreamed their reactions to her New Heights podcast appearance, where she sat next to her boyfriend Travis Kelce, and flooded timelines with excitement and anticipation. For a few brief hours, Swifties felt joy creep in, and everything else seemed to stop.

But was it right to stop? Should we allow ourselves to forget, even for a moment, all the problems in our country and our world?

Especially for those living with constant fear or loss, stopping to celebrate, even momentarily, can feel irresponsible. Yet both history and psychology suggest that joy, even when we are suffering, serves a crucial purpose: it is a means of survival and, at times, a form of resistance.

The Psychology of Pausing

Positive psychology, “a branch of psychology focused on the character strengths and behaviors that allow individuals to build a life of meaning and purpose,” helps us understand why allowing moments of joy matters. Joyful experiences activate our brain’s reward system and counteract stress. Over time, they help prevent emotional burnout, anxiety, and numbness.

The Big Joy Project, a study led by researchers at UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, supports these findings. More than 70,000 participants across 200 countries were asked to practice simple “micro-acts of joy,” such as doing something kind, making gratitude lists, or celebrating another’s happiness. Each act was small, but the results were large: participants' overall sense of well-being, defined as a “composite of their self-rated life satisfaction, happy feelings, and meaning in life,” jumped 26% in just one week, and positive emotions, including “hope, optimism, wonder, amazement, amusement, and silliness,” increased by 23%. In other words, joy isn’t just fleeting, passive pleasure; it’s a tool of resilience with cumulative benefits, and there are techniques for creating it.

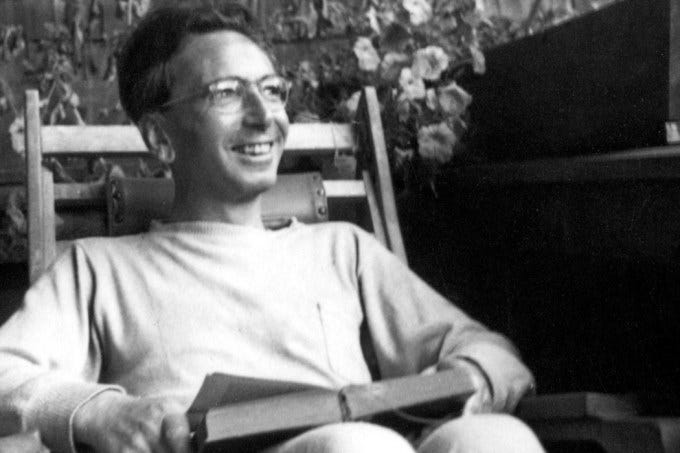

Yet the question lingers: how can people create joy when surrounded by suffering? Viktor Frankl, Holocaust survivor and author of Man’s Search for Meaning, offers a vital perspective. He observed that even when life is stripped to its barest essentials, individuals have the freedom to choose their response. “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.” Frankl illuminates why, across history, individuals and communities have sought brief moments of happiness even under extreme threat. It is not escapism, but an assertion of agency, the choice to find meaning and persevere amid suffering.

The Lesson of The Telly Cycle

Poet Toi Derricotte writes that “joy is an act of resistance” in her work The Telly Cycle. Derricotte explores this idea through the lens of a bond with her pet fish.

Born in 1941 in Michigan, Derricotte often grapples with themes of identity, trauma, and resilience. As a Black woman navigating a society that frequently questions her worth, she consistently finds meaning in the intimate and personal.

In The Telly Cycle, Derricotte asks, “Why would a Black woman need a fish to love?” The question reveals the deep human need for connection. Choosing happiness, Derricotte suggests, is a radical act of defiance. The fish becomes a metaphor for a small, sustaining source of joy, and Derricotte reminds readers that the pursuit of happiness is not frivolous but necessary, a way to reclaim agency over one’s life.

Author and activist Adrienna Maree Brown expands this idea in Pleasure Activism, arguing that oppressed and marginalized communities must reclaim their pleasure. As she explained on NPR’s Code Switch, “I’ve come to understand that is one of the ways we are most easily controlled, when pleasure is taken off the table or made to feel like it's not even something that belongs to our lives. And so the reclaiming of pleasure in the here and now is an important act of reclaiming the wholeness of our lives.” In Brown’s framing, joy is not a distraction from struggle, but a direct challenge to systems that rely on exhaustion, despair, and silence to maintain control.

Derricotte and Brown remind us that joy is a deliberate stance, a refusal to cede one’s humanity. And this act of resistance is not confined to poetry or theory; it emerges again and again in history around the world, wherever communities turn to joy as a means of survival.

Joy in Community

During the Second World War, American GIs and Londoners alike flocked to the Rainbow Corner, a social club near Piccadilly Circus, for reminders of home and normalcy. They played pool and pinball, and enjoyed listening to the jukebox. Even as bomb blasts echoed in the distance, they packed the dance floor. Music, laughter, and parties did not erase the devastation of the Blitz or the grief of families separated by war, but they decreased stress and helped stave off the emotional numbness that comes with living under constant threat. Their joy was not frivolity; it was a survival mechanism.

In the 1990s, when the city of Sarajevo was under siege by Serbian forces for nearly four years during the Bosnian War, musicians carved out a joyful pause. The Sarajevo String Quartet performed 206 free concerts for the public in ruined buildings, their strings trembling in winter's air. These performances did not deny the suffering around them; they affirmed life in spite of it, offering a pause where beauty could exist alongside disaster.

The impulse to reach for joy in the face of devastation continues wherever people are pushed to their limits. During the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic, Italians sang from their balconies, New Yorkers clapped for health care workers, and bakers united at home in Christina Tosi’s Bake Club to bake together and share stories online. Across these moments, joy was not escapism but resilience. A collective insistence that even in disaster, life is still worth celebrating.

Privilege, Protection, and the Ethics of Joy

It is important to recognize that not everyone has equal access to joy. For communities facing daily threats of violence, displacement, or discrimination, the choice to be joyful can come at greater risk. Some Latino communities in the US, for example, have felt pressure to turn down their music, hide their flags, or quiet their cultural expressions, acts of self-erasure meant to avoid harassment by an increasingly militarized immigration system. In these contexts, joy is not only fleeting, it is dangerous.

Those of us with the safety to pause, to post, to laugh, or to immerse ourselves in art do so with freedoms that others may be denied. This awareness need not induce guilt, but it should inspire responsibility. We can use our restored energy to amplify others’ voices, defend their rights, and act for justice.

And yet, as Anne Frank reminds us, even among those for whom everything external is threatened, happiness can endure: “Riches, prestige, everything can be lost. But the happiness in your own heart can only be dimmed; it will always be there, as long as you live, to make you happy again.” In the darkest of times, humans have found ways to assert their humanity, to carve out moments of happiness, and to resist oppression through celebration. Joy, in its many forms, is both shield and weapon, sustaining the spirit and fueling action.

Begin Again

Swift’s The Life of a Showgirl reminds us that what we see on the surface -— glitter, pageantry, glamour — often coexists with struggle, effort, and resilience behind the scenes. Swift explained that the record is about “what was going on behind the scenes in my inner life on the tour.” She added that during her Eras Tour, she was “literally living the life of a showgirl,” one life unfolding under the spotlight and another carried quietly offstage.

This duality, that two things can be true at once, is often reflected in our moments of joy, too. Even amid hardship, we can create spaces to celebrate life, reclaim our humanity, and keep the fight alive. In this way, joy is not merely a pause; it is a source of strength and radical hope.

So, listen to the song, share the laugh, dance in your kitchen, or celebrate the small victories. Let these pauses restore your energy, recharge your empathy, and sharpen your resolve. Let them remind you that even in the face of injustice, despair, or exhaustion, joy can persist.

Isla Flaherty has over a decade of experience making U.S. government accessible and engaging for students from diverse age groups, language backgrounds, and life experiences. She is a recipient of multiple awards recognizing excellence in education and leadership in supporting multilingual communities.

I’m escaping reality filling my joy cup this weekend at Gorge Amphitheater sleeping under the stars in the middle of Washington state. Enjoying 3 days of music with Dave Matthews Band.

The past 2 1/2 years have been spent dealing with stage 3 and stage 4 cancer. First me then my husband! We have learned first hand about the need to find joy every day! Participating in joyful activities has made an incredible difference for us and our family/community. It has brought clarity and helps us focus on what is most needed! We still have cancer but, we are still here and are able to be helpers!