Is Your Zip Code Your Destiny?

How education and economic opportunity became linked to neighborhood

It’s an idea that’s core to the American Dream: where you are from shouldn’t affect your opportunities in life. In a truly meritocratic society, the state, city, or even neighborhood where a person grew up should have little, if any, bearing on outcomes in their adult lives that we might associate with “success,” such as education, health, income, or happiness.

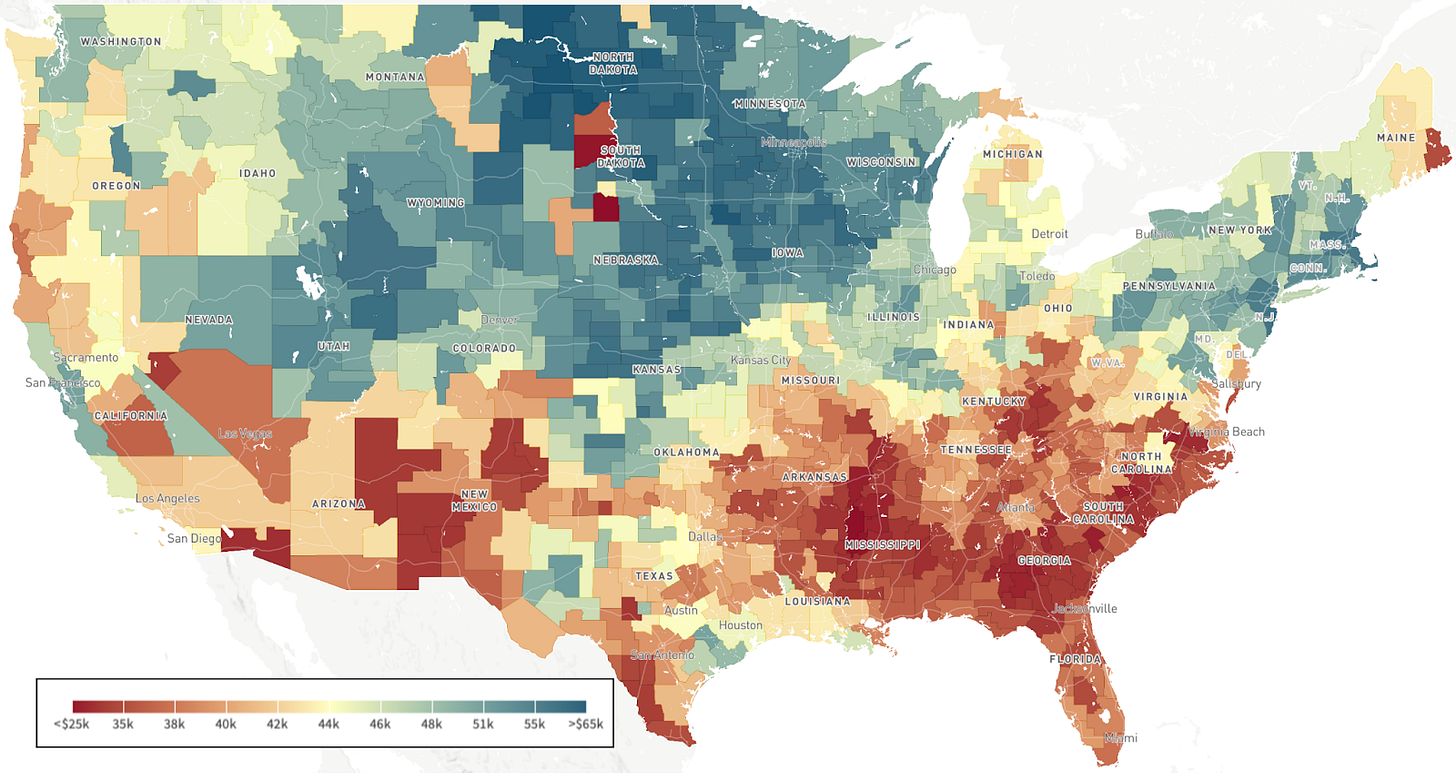

Yet decades of social science research suggest that growing up in one neighborhood rather than another can have a meaningful, and measurable, impact on your life. For example, the map below shows the average annual income of adults in the United States based on the neighborhood where they grew up.

Americans’ incomes as adults can vary depending on where we grew up

Average annual household income in 2014–15 of children who were born in 1978–83 and grew up in the shaded areas below

We can see clear regional variation. On balance, growing up in the South in the US is associated with much lower average annual incomes than growing up in much of the Northeast or upper Midwest. For example, the average annual income of someone who grew up in Macon, GA ($36k) is about half that of someone who grew up in Sioux Center, IA ($63k). (By the way, these numbers come from an interactive map, which I highly encourage you to explore!)

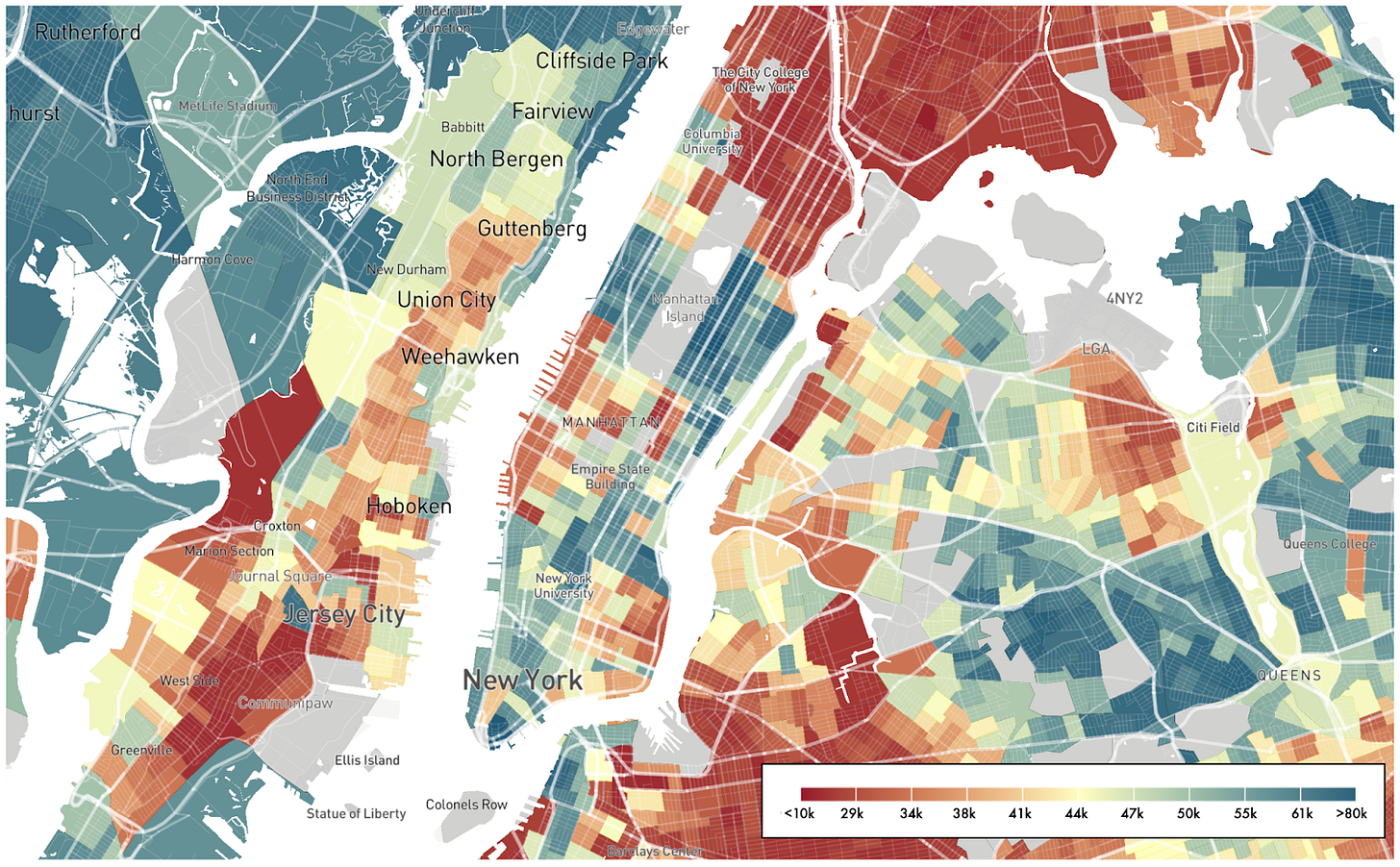

Geographical disparities also show up at far more granular levels. The map below shows differences in average annual incomes across different neighborhoods, and even sub-neighborhoods, in the New York City area. (These maps are organized by Census tracts, which are small geographic designations of about 4,200 people each. There are about 70,000 Census tracts in the US.)

Income differences are apparent even at the hyper-local level

Average annual household income in 2014–15 of children who were born in 1978–83 and grew up the shaded areas of New York City below

In the NYC closeup we can see that there are parts of the city where walking even a few blocks can mean vast changes in eventual average incomes for children growing up there. For example, if you wandered down the west side of Manhattan or headed just east from New York University, you’d quickly find yourself walking from a $60k region into a $30k one.

And it’s not just income. Effects of the neighborhood where a child grows up have been observed for decades, in all kinds of outcomes. Where a person grows up has been found to influence their credit score, hours worked, exposure to pollution, access to health care, political participation, and even likelihood of becoming inventors, among many other outcomes.

Okay, place matters… but why?

Why does the neighborhood where a child grows up in the US seem to matter so much? Is it schools? Economic resources? Peer influence? Safety? Something else? All of the above? And why do we have those differences in these neighborhoods in the first place?

While the statistical correlations between a child’s neighborhood and their adult outcomes is airtight, establishing causality is much harder. This is because, until recently, most of the research has had to rely on what scientists call observational data, which is data based on, well, observations (you’re welcome!). Observational data is about things that happened in the world that we chose to record in some way. Things like the average annual rainfall in South Carolina, lung cancer rates among young men in Appalachia, or the percentage of households that adopted a dog during Covid are all examples of observational data. Something happened in the world (hurricanes, coal mining, a global pandemic), and scientists tracked aspects of it in real time or reconstructed them after the fact.

Observational data is great, and it’s often all we have for a lot of things we might want to study, but to understand cause and effect, we need experimental data, which is data based on (you guessed it!) experiments. As I’m sure you already know, in an experiment, the researcher randomly assigns some participants to some kind of treatment (e.g., taking a drug) and the rest to a control or placebo (e.g., taking a sugar pill). If the treatment and control groups are reasonably similar apart from whether they got the treatment or the placebo, we can conclude that any changes in the treatment group are due to the treatment.

Experimental data is pretty much the closest scientists can get to establishing causality. It’s super powerful — and it’s also very hard to get in the real world. You can’t ethically (or financially, to be frank) randomly assign a bunch of people to live in hurricane zones, work in coal mines, or experience a pandemic. Similarly, you can’t randomly assign children to move to different neighborhoods to see how variations in schools, peers, crime, environment, or other factors affect adult outcomes…

An extremely cool experiment

Or can you? Between 1994 and 1998, the US government partnered with social scientists to conduct an actual experiment about the effects of growing up in different neighborhoods. In the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) experiment, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development invited families living in high-poverty areas in five major US cities to apply to participate in the study. Of the 4,600 families that applied, some were randomly given subsidized housing vouchers to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods, others were given regular housing vouchers with no specification about where to move, and a third group was a control (meaning they were not given vouchers).

Of course, we shouldn’t expect that we’d see results from these “treatments” overnight, but by the early to mid 2000s researchers were able to establish a few exciting differences between the groups, including that families who moved to the lower-poverty area generally saw improved mental health, lower rates of diabetes, and improvements in safety. But, surprisingly, these same studies found limited evidence that moving to “better” neighborhoods improved outcomes for children overall or increased families’ economic self-sufficiency.

Things took yet another dramatic turn when three researchers returned to the MTO data in the mid 2010s. By this time, children who were very young when their families participated in this experiment were old enough to be entering the labor market. And, based on other studies in the interim that had started to suggest it matters how long people spend in a neighborhood, these researchers specifically considered differences in outcomes for children who were young (under 13) or older (13–18) when their families moved.

Dividing children up into younger or older at the time of the experiment opened up a whole new set of discoveries. It turned out that younger children who moved to lower-poverty neighborhoods ultimately had higher incomes, were more likely to attend college and to attend better colleges, were less likely to live in lower-poverty neighborhoods as adults, and were less likely to be single parents.

For older children, however, the effects were either zero or even slightly negative: individual income for older children in the treatment group seemed to be slightly lower than income in the control. The researchers speculate that this may reflect a disruptive effect of moving to a new environment: for older children with established social networks and familiar schools and teachers, the harm of severing those ties may outweigh the benefits of moving to a lower-poverty area.

The role of education

While now we’ve established some compelling evidence for a causal relationship between the neighborhood where a child grew up and various adult outcomes that we might care about, we still haven’t discussed my favorite concept in all of science: the causal mechanism. My preferred definition for a causal mechanism is that it’s: the thing that causes the thing to cause the thing. But because that definition is preferred by zero other people, I can also tell you that the causal mechanism is the reason one thing causes another. If growing up in a lower-poverty neighborhood causes a child to have a higher income as an adult, the causal mechanism is the answer to the question: What is it specifically about the neighborhood that is driving the higher income?

I’m oversimplifying a bit, but the research conducted since these studies has led many experts to think of the impact of where you grew up as the result of “exposure” to “neighborhood effects.” Specifically, the more years a child from a low-income family spends in a less-poor neighborhood, the greater the “effects” of that neighborhood on things like income as an adult.

Further research has also explored specific aspects of that effect, including education, peer influence, pollution, violence, and criminal justice policies. While there are a lot of nuances to each, in general all the above aspects of a neighborhood seem to matter, with the empirical evidence particularly strong around education. Lower-poverty neighborhoods tend to have better schools and teachers, which are associated with higher academic achievement and college enrollment, as well as lower criminality and teen pregnancy.

In fact, while there are still open questions about the extent to which different components that make up a “neighborhood effect” matter, recent research (albeit in Canada!) suggests the schools in a neighborhood may be responsible for at least 50% of the overall neighborhood effects we see.

Why is education tied to neighborhoods in the first place?

We’ve seen that the neighborhoods where kids grow up can exert a big effect on their lives as adults, and increasing evidence suggests that education is one of the strongest mechanisms by which neighborhoods exert this effect. This suggests two possible pathways by which we can improve outcomes for children, especially low-income children, in the US. One is to increase housing mobility so that more families with young children can move from high-poverty areas to lower-poverty areas where schools typically have more resources. The other is to relax the ties that specific schools have to specific neighborhoods.

Before the American Revolution, education in the US was a local effort run by churches, homeschools, community schools, and even some boarding schools. After independence, education was built out at the local and state levels, including through ordinances that required sections of land to be allocated to public schools. Even today, there is language in every state constitution about education, while there is nothing about it in the US Constitution (though the Tenth Amendment is understood to imply that states have power to manage public schooling). In fact, in 1973, attempts to enshrine access to education as a federal right were shut down by the US Supreme Court. To this day, the vast majority of funding for schools comes from state (46%) and local (44%) sources as opposed to federal funding (11%).

One of the consequences of this system, however, is that if schools are reliant on local funding, then the more money an area has, the more money a school will have. The formation of formal school districts, which are related to but not exactly overlapping with ZIP codes, thus meant that if you had people living in your school district who bought more expensive homes, then more money from property taxes would be available for schools. Other research shows that this effect gets amplified over time as affluent neighborhoods attract better teachers, which creates better schools, which increases property value, which attracts more affluent residents, and so on.

Because schools are funded by local taxes, all residents of those districts can send their children to school for free. But this also means there are restrictions on allowing children to go to schools outside their home districts. It is possible, but it can be complicated, and the rules vary by state. So what all of this means is that we now live in a world where your neighborhood dictates what school you can go to, and if your neighborhood isn’t wealthy, then it’s unlikely your school will be, either.

It’s not just that this setup prevents many people from living in areas where there are higher-resourced schools. One of the most sinister parts of the story is redlining, a policy that came into widespread use in the 1930s at the encouragement of the federal government, in which people were denied mortgages, insurance, loans, and other financial services based on where they lived. Specifically, neighborhoods in cities across the US were labeled “red” or “hazardous” if they met certain criteria, including a large Black or mixed-race population.

For decades, this actively prevented many people in Black and other predominantly non-white communities from getting mortgages that would allow them to buy a home or move to a wealthier neighborhood. While the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed redlining in principle, much damage had already been done, and housing discrimination is still an issue today, including through algorithmic bias. (That’s when computers are given data that reflects existing biases in society and we thus end up training machines to make decisions as biased as ours or even more so.)

Thus, we’re in a situation where being wealthy gets you access to better schools, and being at better schools can help you become more wealthy. As exciting as the “neighborhood effects” findings are for the possibilities of increasing economic mobility for children in higher-poverty areas, these effects can also increase the barriers to entry into neighborhoods that would be most helpful to children. If there were an obvious answer to this catch-22 I would tell you about it (and I’d have a Nobel Prize), but in general, continuing research on the mechanisms by which education makes a difference (high quality elementary school teachers, great kindergarten, and mobility institutions are some promising ones) can offer some pathways forward. And I am biased, but I am always in support of more experiments.

Thank you Andrea! Great piece connecting statistics to our lived experiences and causes (with some hilarious but effective explainers of how cause and effect is measured!).

I grew up in a lower income neighborhood of a higher income suburb. My home was walking distance to a nicer elementary school but not walking distance to the not-as-nice elementary school that was in our district, so we were driven to the not-as-nice school from kindergarten to 3rd grade. Both schools were great in their own ways but when I transferred to the nicer one in fourth grade the difference was stark.

In the former we had kids trying to set fire to the school. At recess one day I fell from high up when one of the swinging bars broke and I fell onto my back, hitting my head and almost getting seriously injured. There was a creepy music teacher who found excuses to separate the boys and girls and would give the girls lots of attention while sending us boys to go run laps around the track for no reason. One teacher was suspended but not fired for wrapping duct tape around a student’s mouth and body. There are probably a lot of other wild things that happened that I was too young to process.

Anyway, when my mom started working at the nicer school as a teacher, somehow that meant my siblings and I could go to the nicer school even though my neighbors couldn’t. Night and day. I went from having 40 classmates to 20. All of my teachers got to know me individually, made learning fun, we had all new equipment, and the school building itself was new, not crumbling. All of this because my neighborhood’s zip code ended with a 4 instead of a 2.

Thinking back to yesterday’s essay about homeschooling that is witnessing an exodus from public schools, this piece feels like it has the missing part of that equation: taxes and funding. It seemed like that piece was making the case that every public school was becoming a learning-free zone where kids take tests all day and hate where they go to school. Maybe that’s the case now, I’m not sure. But in the 90s and 00s when I was in grade school we had plenty of standardized testing, and yet I feel like I got a pretty good glimpse at what had more of an impact: that the love for learning came from access to resources. Is this the best system we can come up with? It feels antithetical to the idea of public education to then have the quality depend on the affluence of surrounding residences.

My ears perked up when Andrea mentioned a Supreme Court case in the 70s is why courts have determined that kids don’t have a constitutional right to education. The case was San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez (1973), where Mexican-American parents from the Edgewood district in San Antonio challenged Texas’s school funding system. Their district, despite having one of the highest tax rates in the county, received only $37 per pupil while the wealthier Alamo Heights neighborhood got $413 per student. A three-judge federal district court actually ruled in their favor and declared education a fundamental right under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. But then the Supreme Court reversed it 5-4, with Justice Powell writing that education was neither “explicitly nor implicitly” found in the Constitution, and therefore not protected by it. Justice Marshall’s dissent argued that education must be considered fundamental because of its “close relationship between education and some of our most basic constitutional values,” specifically pointing to its necessity for exercising First Amendment rights and the right to vote.

My current obsession is my newsletter thinking about which constitutional amendments we most desperately need, being that we used to amend the constitution at least once a decade on average, and yet we haven’t really done so since 1971. Although an amendment was ratified in 1992, it did not introduce a new right or structural reform, leaving the United States in a de facto half-century dry spell when it comes to substantive constitutional change.

Is a right to education one that should be there?

Here’s my question to fellow readers: if an amendment to protect education should be added, what exactly should it protect? Based on the Rodriguez case and what’s happened since, an amendment could potentially guarantee every child access to a quality public education regardless of where they live, require equitable distribution of educational funding that isn’t tied to local property wealth, and establish minimum standards that states must meet. The Rodriguez dissent suggested education is essential for meaningful participation in democracy. Perhaps an amendment should explicitly connect the right to education to the exercise of other constitutional rights like voting and free speech. There is already state-level precedent for this working. In New Jersey, a series of rulings beginning with Abbott v. Burke forced the state to dramatically increase funding for its poorest districts, resulting in measurable gains in student outcomes. Similar rulings in states like Kansas and Washington have compelled legislatures to revise funding formulas when courts found them incompatible with constitutional education guarantees.

Would love to hear what others think the language of such an amendment should include.

I would love to see an article about improving the public school system in the United States. There has to be a way to ignite a new round of good teachers obviously money would help, but it’s not everything. Personally think it’s really important to get off on a good start at a very young age.