Is Religion the Answer for Democrats? James Talarico Thinks So

Plus: A presidential historian's take on Trump and Congress

by Andrew Kordik

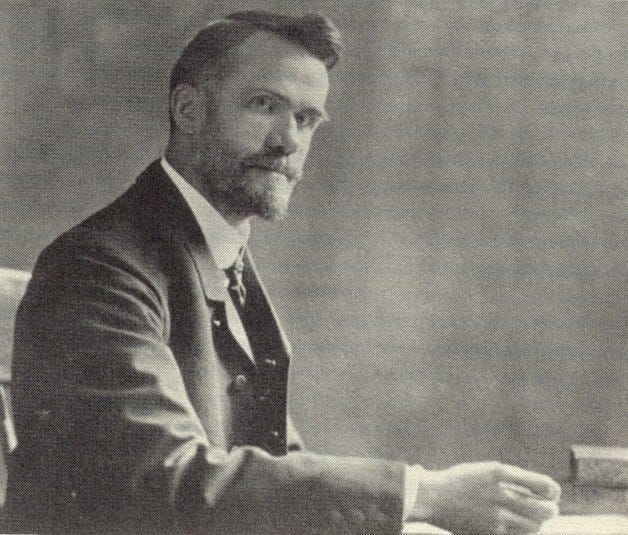

Speaking from the bed of a rusty old pickup, State Representative James Talarico — with a microphone in hand and the collar worn loose on his dress shirt — addresses a rapt crowd in front of a quaint white church and a barn adorned with the Texas flag. The scene, chosen as the setting for his first campaign ad, is chock-full of the small-town Texas charm that characterizes the 31-year-old Presbyterian Democrat now running for the US Senate.

“The biggest divide in our country,” he begins, “is not left vs. right; it’s top vs. bottom.” Then Talarico quickly pivots from class politics to faith: “My granddad was a Baptist preacher in south Texas. He taught me that we follow a barefoot rabbi who gave two commandments: love God and love neighbor.” He continues, “2,000 years ago, when the powerful few rigged the system, that barefoot rabbi walked into the seat of power and flipped over the tables of injustice. To those who love this state, to those who love this country, to those who love our neighbors: it’s time to start flipping tables.”

If this feels new, it’s because for decades Democrats — wary of mixing faith and politics — have largely ceded religion to Republicans as white working-class Christians fled to the GOP. Between 1998 and 2001, according to the Survey Center on American Life, white evangelical support for Democrats declined from 41% to 19%. And the party’s struggles have only deepened since then: In 2024, Kamala Harris received 36% of the Christian vote but only 26% of the white Christian vote. Among white evangelicals, her support was an even lower 14%, per the Public Religion Research Institute.

But in his long shot bid to unseat Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX), James Talarico is betting that faith can reconnect these voters with the Democratic Party. Speaking to The New York Times, Talarico says, “Progressives have got to understand that separation of church and state is not the separation of faith and politics. Unless we do, we’re going to continue losing elections.”

Talarico’s bet is bold and uncertain, but it’s not without precedent.

In framing progressive goals within Biblical teachings, the Texas politician is resurrecting the Social Gospel Movement, a late 19th- and early 20th-century political tradition that emphasized the values of Jesus in challenging robber barons and advocating for poor, marginalized workers. More than theology, the Social Gospel was a philosophy of political action for Christians, one that called them to fight for working-class Americans.

Walter Rauschenbusch, the movement’s leading theologian, argued that “whoever uncouples the religious life and the social life has not understood Jesus” and urged Christians to transform “life on earth into the harmony of heaven.” This belief underpinned a generation of progressives — from President Theodore Roosevelt to populist William Jennings Bryan and socialist Eugene Debs — who fought for reforms in child labor, working hours, housing regulation, and more.

Yet in the years since Jimmy Carter’s campaigns, which presented his evangelical background as foundational to his commitment to social justice, the Social Gospel has rarely appeared as an animating force in progressive politics — with the exception of Sen. Raphael Warnock, who represents a Social Gospel tradition that has remained strong in many Black churches.

Talarico believes his renewed Social Gospel campaign will stop the party’s bleeding with white working-class Christian voters. And if he can claw back even a few percentage points among these voters, Talarico just might disrupt politics in Texas — where a Democrat has not won statewide office since 1994 — while also demonstrating that there’s still an appetite for the Social Gospel.

For perspective, Beto O’Rourke — who suggested denying tax-exempt status to religious institutions that oppose same-sex marriage — lost the 2018 Senate election to Ted Cruz by 215,000 votes as Cruz earned 84% of the white non-college-educated evangelical vote, according to CNN. If we assume that white evangelicals represent 23% of Texas voters, Beto O’Rourke could have won the election with a 6% increase in his share of their vote.

Despite being equally progressive, Talarico may prove more appealing than O’Rourke to Christian voters. He’s certainly less likely to alienate them.

The critical difference between Talarico and other progressive candidates is not merely that he’s a Democrat and a Christian; it’s that he’s a progressive Democrat because he’s Christian. Channeling the Sermon on the Mount, Talarico told followers, “You can’t call yourself a Christian and deny health care to the sick. You can’t call yourself a Christian and vote to cut food stamps to the poor. You can’t call yourself a Christian and reject the stranger seeking asylum at our southern border. You can’t call yourself a Christian and destroy God’s creation with greenhouse gases. And you can’t call yourself a Christian and discriminate against your neighbor because of their race, gender, or sexual orientation.”

In true Social Gospel spirit, Talarico also encourages Christians to confront economic inequality, asking followers, “What would Jesus do about a tax system that benefits the rich over the poor?... Would he stay in his room and pray?” Talarico’s Christian style of expressing anti-billionaire, pro-worker beliefs presents another stark contrast with progressive Democrats like Beto O’Rourke or Bernie Sanders, who favor similar policies but use abstractions like “justice” rather than moral lessons from the Bible to frame them.

Talarico, by contrast, is trying to appeal to Christians by grafting widely known religious stories onto his progressive, working-class policies — not from cynicism but from conviction that Christian values are aligned with progressive politics. Speaking to Politico, Talarico said, “In my reading of history, the most successful progressives — whether it’s in the labor movement, the civil rights movement, women’s movement, farm workers’ movement — they embed themselves in those stories, and then use those stories to propel their movement forward.” Talarico firmly believes that unless Democrats develop faith-based narratives, they will continue losing elections.

Time will tell whether he is right, but for now, he is all in.

To deliver his message, Talarico, resembling a modern itinerant preacher, travels far afield from traditional liberal media. He now has over a million followers on TikTok and has eagerly accepted interviews with Fox News and The Joe Rogan Experience. After the aspiring senator explained to Joe Rogan how religion shapes his view of class politics, an excited Rogan responded, “You need to run for president.”

And it’s not only Rogan. In the past year, Talarico has become a rising star in the Democratic Party. So much so that in its first three weeks, his campaign broke Texas quarterly fundraising records for Senate candidates, raising $6.2 million. That’s $2 million more than his primary opponent Colin Allred, according to ABC News in Dallas.

To be sure, Talarico remains the underdog, trailing Allred by seven points in early polling. Yet he also appears to be the momentum candidate. According to Public Policy Polling, Talarico holds a 55–18 lead with young voters, whom Texas Democrats have struggled to capture in recent years. And though he enters with a dramatic name recognition gap, Talarico leads by two points in polls that introduce both candidates to respondents.

In other words, there is reason for optimism in the Talarico camp.

And his campaign believes that if Talarico continues crafting stories that center progressive Democratic policies within the moral arc of Christianity, his name recognition gap will close, propelling him to victories in the primary and general elections.

What happens from there, only God knows.

Congress? Never Heard of It

by Alexis Coe

Tyrants make laws. That’s why the Framers built a Constitution to stop them. Article I strikes like a hammer: “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States.” All.

James Madison, writing in Federalist No. 47 in 1788, warned that the “accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands… may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.” In Federalist No. 73, Alexander Hamilton calls the veto “a shield to the executive” because he saw it as a defensive safeguard: the president’s way to protect his office (and, by extension, the people) against rash, unjust, or unconstitutional laws passed by Congress. The veto was not intended as a power to originate policy or to let the president write laws by blocking them for political reasons — Congress remained the body meant to legislate.

The Revolution was proof enough. The Declaration of Independence devotes its longest section to George III’s abuses: imposing taxes without consent, creating offices to harass colonists, dissolving legislatures at will. Parliament existed, but royal prerogative reigned. Americans swore never again to live under a ruler whose word was law.

Presidents have always tested that boundary. In 1832, Andrew Jackson vetoed Congress’s recharter of the Bank of the United States simply because he despised it. His enemies caricatured him as “King Andrew I,” enthroned in robe and crown.

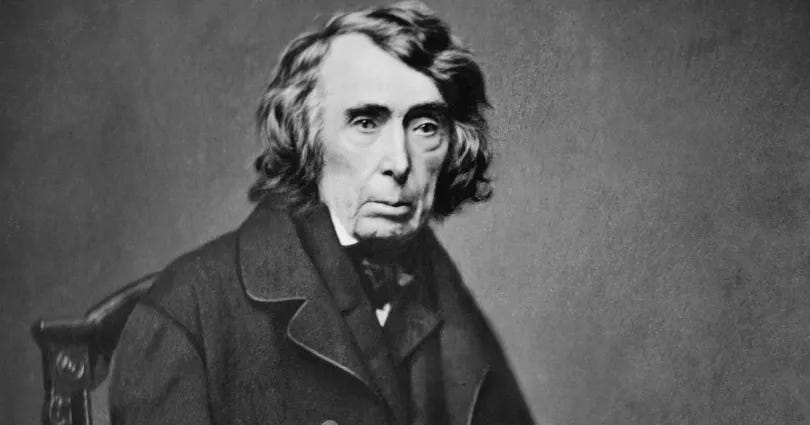

Even at the peak of national emergency, presidents could stretch enforcement, but they could not legislate. In 1861, Abraham Lincoln suspended habeas corpus without congressional approval; Chief Justice Roger Taney, in Ex parte Merryman, ruled that only Congress could suspend the writ. In the 1930s and ’40s, Franklin Roosevelt signed thousands of executive orders, but the Social Security Act (1935), the Securities Exchange Act (1934), and the National Labor Relations Act (1935) all came from Congress.

And yet President Donald Trump makes claims to legislative power the Constitution does not grant. “We’re just gonna do it,” he scoffed when the point was raised that only Congress could change the name of the Department of Defense to the Department of War.

Courts have rebuked presidents for executive overreach before. The Supreme Court recently struck down President Joe Biden’s student-loan forgiveness plan as an unlawful use of administrative power. But that episode, while significant, still presumed Congress held the legislative keys. Trump’s posture is different: he doesn’t test the edges of executive authority, he collapses the distinction between the branches altogether, treating legislation itself as a presidential prerogative.

Trump’s actions match the words. In March 2025, his allies introduced the Dismantling Government Act (H.R. 1295), which would allow him to abolish entire agencies unilaterally. Imagine the Department of Education erased overnight because one man chose to — a man who never served in Congress.

And even without such a law, he has pursued the same end through attrition; he’s defunded programs, withheld appropriations, and instructed administrators to dismantle their own agencies from within. Where Hamilton imagined the executive executing, Trump imagines the executive extinguishing.

In February 2025, Trump signed Executive Order 14215, compelling agencies — including those Congress deliberately insulated, like the FCC and SEC — to accept his reading of the law as the only “authoritative” one. Legal allies seemed to spelled it out: “Trump is the law for the executive branch.” Congress may pass legislation, but under this doctrine, Trump alone decides its meaning. No president had done this before. Independent agencies had always been expected to exercise their own legal judgment, subject to review by Congress or the courts. Trump replaced that tradition with something new: not influence, but command.

And the pattern widens. His administration has sought to strip federal workers of appeal rights after they were fired, leaned on judges who ruled against him, and threatened law firms that challenged him. “IF YOU GO AFTER ME, I’M COMING AFTER YOU,” he wrote on social media in 2023, and he certainly seems to be making good on the threat. Each act is rehearsal for the main event: a presidency that not only enforces law but punishes anyone who says, You cannot write it yourself.

The contrast is brutal. Washington issued eight executive orders. Trump is attempting to crown himself with a legal pad. The Framers did not draft parchment to sanctify that. They fought a war to bury it.

If October 2025 ends with Americans letting a president steal Congress’s pen, they will not be living in a republic. They will be wandering a wax museum version of one, admiring the lifelike figures, blind to the fact that the whole thing is melting.

Alexis Coe, a presidential historian, writes the Substack Study Marry Kill. She is a history columnist for The New York Times Book Review, a senior fellow at New America, and the bestselling author, most recently, of You Never Forget Your First: A Biography of George Washington.

Talarico earned my admiration when he stood up to Gov. Abbott’s education voucher scheme and the bill to command every classroom post a 10 Commandments poster. He eviscerated his opponents in the debate by pointing out they were violating the commandments by voting on Saturday (Sabbath). He reminds me of Obama’s rhetorical eloquence and puts the GOP performative Christianity to shame, exposing its hollowness. And I am thrilled to finally have a senatorial candidate I can wholeheartedly vote for.

Talarico takes Jesus back. Jesus was not a conservative by today’s standards. He was, dare I say, “Radical Left”? I love that Talarico isn’t afraid to embrace Social Justice Jesus. But make no mistake - he believes in a strong separation of church and state unlike the current chucklehead Christians in office. “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and to God the things that are God's” Matthew 22:21 and Mark 12:17. This is an ode to secular authority.

But not sure that part made it into the Trump Bible?