Is DEI Discrimination? Here Are the Arguments on Each Side

The Trump administration is cutting hundreds of millions in federal funding from schools, colleges, and organizations that continue with diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts.

In September alone, the US Department of Education, under the Trump administration, announced:

Chicago Public Schools will lose $23.3 million in the years to come for moving ahead with a DEI initiative called the Black Student Success Plan that began earlier this year.

Nearly $170 million in grants that funded college preparation and career-readiness counseling are now canceled at schools with any connection to DEI.

Several grants, totaling $350 million, are being withheld from minority-serving institutions because they are designated for colleges with high minority populations.

The desirability of such programs has long been debated. Some see DEI as necessary to reduce discrimination — a position the Biden administration took — while others see DEI itself as discrimination, which is the position the Trump administration takes.

Under the Biden administration, DEI was mandated. Under the Trump administration, it’s been banned. On Biden’s first day in office, he signed an executive order aimed at “advancing racial equity,” which Trump essentially reversed on his second day back in office with an executive order that called for “ending illegal discrimination.”

Previously, universities were expected to pursue diversity within their student bodies as a “compelling interest” and received funding specifically for adopting DEI programming. Now, diversity cannot be pursued as a goal.

One administration says “racial equity,” the other says “illegal discrimination,” and somehow they are talking about the same thing. So which is it? Are efforts to achieve equal outcomes fair because they counteract discrimination, or are they unfair because they create discrimination?

Let’s consider the arguments each side makes, and trace some of the history, to help you decide for yourself.

The history of affirmative action

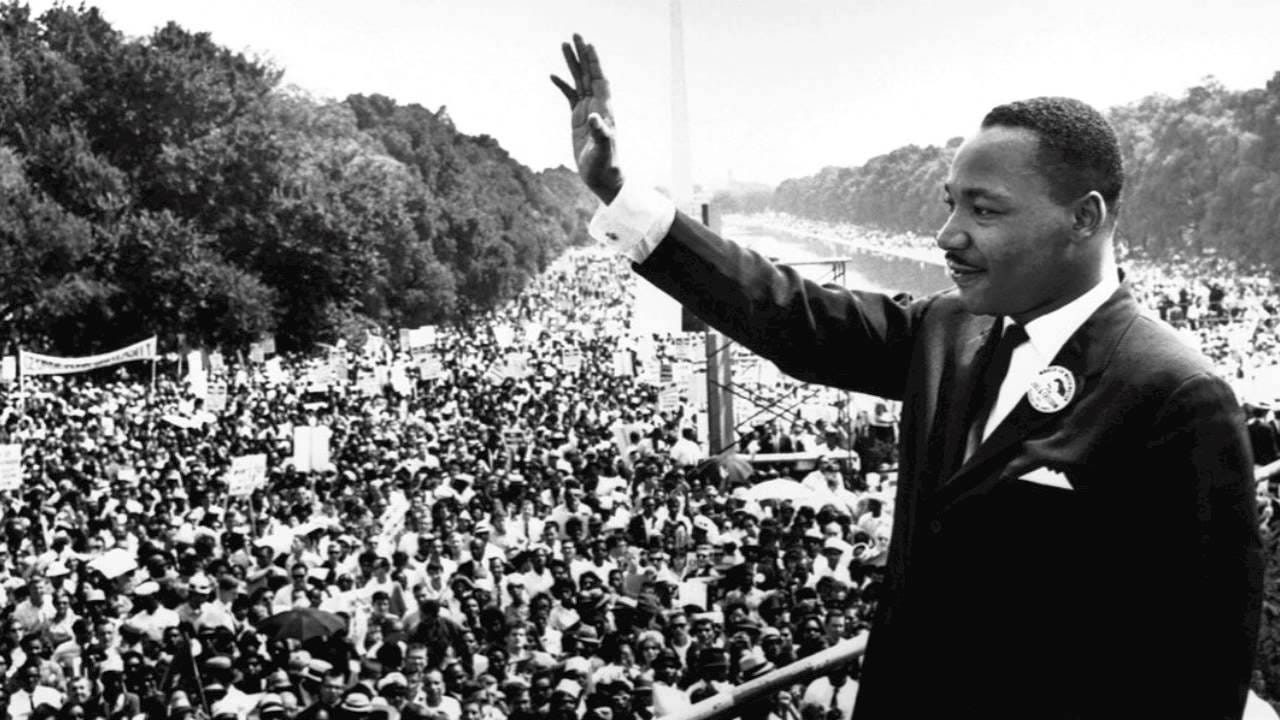

In his 1964 book, Why We Can’t Wait, Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, “A society that has done something special against the Negro for hundreds of years must now do something special for the Negro.” He was repudiating a popular stance at the time, that discrimination should come to an end but nothing should be done to make up for past discrimination. In King’s view, that would come short of true equality. “For it is obvious that if a man is entered at the starting line in a race three hundred years after another man, the first would have to perform some impossible feat in order to catch up with his fellow runner.”

This is the essence of affirmative action. The commitment to “take affirmative action” against racial discrimination was first penned by President John F. Kennedy as he introduced the Committee for Equal Employment Opportunity in 1961 and appeared again in a 1965 executive order signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. In practice, this meant things like providing scholarships to minority students, recruiting job candidates from minority groups or giving special training to them, conducting outreach among minority communities to make them aware of opportunities, relaxing university-admission or professional standards for minorities, or setting quotas for their inclusion.

The goal was to bring about a society less distorted by racial discrimination. But the risk was that some of these policies would end up discriminating against individuals in the majority by requiring them to clear a higher bar in order to have the same opportunities.

In the 1960s, there was clearly a lot of ground to make up to achieve racial equality. As time went on, though, the question became, How much proactive intervention is needed, and for how long? At what point does the race eventually become fair? Though wide outcome gaps remained throughout the 20th century, some people feared that measures toward equality were being taken too far and previously marginalized groups were being given the upper hand.

Not always able to strike this delicate balance, affirmative action was challenged and reformed several times over the years — most significantly in the 1978 Supreme Court case University of California v. Bakke. At the University of California Medical School at Davis, some spots were reserved for qualified minorities. When a white man filed a suit because he was twice denied admission despite having higher relevant test scores than those of the qualified minorities who were admitted, the Court ruled in his favor.

The Court decided explicit racial quotas could not be used, but granted that race could be considered as one of many factors in the admissions process. In the decades following this decision, race-conscious college admissions continued under “strict scrutiny” standards: they were allowed only if they were narrowly tailored to the goal of pursuing diversity in higher education, which was deemed a compelling government interest. They were allowed, that is, until the final blow to affirmative action came in a 2023 Supreme Court decision.

Dealing with discrimination

In Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. Harvard and a companion case, SFFA v. University of North Carolina, the plaintiffs challenged the use of race-conscious admissions. For them, dismantling affirmative action was about ending discrimination against Asian and white students in the admissions process, which was an unintended result of affirmative action.

The plaintiffs contended that Asian applicants had to meet higher standards to have the same chance of being admitted as applicants of other races — and that both Asian applicants and white applicants would see increased admissions if race were not considered. In these cases, the Court struck down race-conscious admissions, ruling that they violate the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, “Eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it.”

Proponents of affirmative action were devastated by this decision. DEI advocates, such as activist and scholar Ibram X. Kendi, typically say that unequal outcomes are evidence of discrimination. (According to Kendi, to believe otherwise is to believe that some groups are naturally more intelligent than others, which is racist.) That’s why in his 2019 book, How to Be an Antiracist, he claims, “The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination.”

The Court’s decision was cheered as needed progress among those who believe that outcome gaps are a product of something other than deliberate discrimination, that equal outcomes should not be artificially achieved, or that individuals should not be discriminated against for the sake of a collective good. In her 2018 book, The Diversity Delusion, conservative scholar and author Heather Mac Donald argues that when race-conscious policies advantage certain racial minorities, they introduce discrimination that wouldn’t otherwise exist, and they resemble the very thing they are meant to protect against.

The 2023 Supreme Court ruling functioned as a kind of litmus test. If you believe that racial discrimination against Black and Hispanic people in particular is, for the most part, a thing of the past, then affirmative action’s end was overdue. If you believe that racism against Black and Hispanic people is severe and ongoing and that affirmative action is the right way to address it, then affirmative action’s end was premature — and was further evidence of the tragedy of racism.

Or you could fall somewhere in-between: you might believe that racism is ongoing, but that affirmative action — in its flawed form — led to its own form of discrimination in a zero-sum competition for admission and that its time had come.

The debate continues

The implications of the SFFA cases have only grown since Trump returned to office. The president specifically mentioned the Supreme Court’s decision in his executive order banning DEI programs. The Court had not discussed contexts other than university admissions, but the administration is taking the race-blind logic of the ruling and applying it to all aspects of schools that receive federal money. According to this view, any DEI programs seeking to boost inclusion of some racial groups are a form of discrimination against other groups, just as trying to boost Black or Hispanic enrollment at universities is discrimination against other applicants.

Secretary of Education Linda McMahon articulated this view when discussing recent funding cuts. “Discrimination based upon race or ethnicity has no place in the United States,” she said. “Our commitment to ending discrimination” means “fighting to ensure that students are judged as individuals, not prejudged by their membership of a racial group.”

Representatives of minority-serving institutions responded with concern — not just for minority students but for all students at the schools affected by these cuts. “Without this funding, students will lose the critical support they need.”

The Department of Education will continue to see major shakeups. As these grants and programs end, it’s unclear what new arrangements will take their place. McMahon says the Department of Education is still in the process of deciding how to “re-envision” how federal education funds will be distributed. In the latest move, just this month, nine colleges were sent “compact” agreements that involved (among other things) eradicating DEI in exchange for preferential access to federal funding. Definitive plans haven’t been announced, but change is coming and, clearly, the stakes are high.

We can all agree that we don’t want there to be any discrimination or racial injustice in our education system. We just can’t seem to agree on what the real injustice is.

This is such a clear explanation, and I really appreciate it the way you laid out the arguments. I would add a note that this piece focuses mostly on the affirmative action argument, though, and DEI efforts are so much more broadly construed by educational institutions and workplaces - especially the inclusion - and so even if someone disagrees with the quotas addressed by the courts, it’s important to note that the administration is coming for a much broader set of actions and activities.

Kendi’s point of view isn’t really an opinion, it’s fact, right? When looking at the diversity of our business leaders in Fortune 500 companies we still have about 60% of board seats occupied by white men. White males make up 30% of the population, yet make up about 90% of the CEOs.

There are two ways to explain that: systemic discrimination, or genetic supremacy of white males.

I appreciate exploring the other side in good faith, and there are some obvious ways to tweak policy to better align with fairness, but their arguments that recruitment tactics to counteract the default discrimination is worse than the default discrimination itself are the definition of white supremacy.