How Trump Can Get Things Done in Congress

An old Senate rule could be all he needs

Today’s post comes to you from Gabe Fleisher, who writes the popular Substack newsletter Wake Up to Politics. He’s a journalist who knows government —and DC— far better than most. He’s going to be joining me here occasionally on The Preamble, sharing his knowledge and reporting with all of you. I hope you’ll enjoy his work as much as I do.

Republicans have narrowly won the House and Senate, and they have big plans for what they expect to accomplish once Trump takes office. They’re already hard at work preparing ambitious pieces of legislation that they hope to swiftly move through both houses.

But, wait… what about the filibuster? Don’t all pieces of legislation need to get 60 votes to get through the Senate?? How can they expect to get anything done with such slim majorities?

Great questions. The answer is with “reconciliation,” a process that is responsible for some of the most consequential laws of the 21st century, from the Trump tax cuts to Obamacare. The tool is little-known, and even less-understood, with origins that often get swept under the rug. Ask anyone in DC, what exactly are we reconciling? and you’ll be met mostly with blank stares.

The Birth of Reconciliation

The reconciliation process dates back to the 1970s — and, the truth is, lawmakers didn’t set out to give themselves a “get-out-of-the-filibuster-free” card. The filibuster is a process set up by the Senate, where senators can block a bill from getting to the floor for a vote by engaging in unlimited debate.

In the past, the Senate required members to physically get up and talk to continue to “engage in debate.” (You’ve probably seen this on TV with people reading their grandmother’s recipe books to keep the clock running.) Eventually, so many Senators would get sick of the stalling tactic that they would band together to shut up the speaker, voting to end the debate.

But in the 1970s, the talking filibuster was eating up so much of the Senate’s time that they changed the rules. The net effect is now that in order for a bill to even come to the floor, sixty Senators must agree to allow that to happen.

Again, not 60 votes to pass the bill. That only requires 51. It’s 60 votes to decide to bring the bill to the floor to even be able to talk about passing it.

But under the reconciliation process, the filibuster is bypassed. When lawmakers made the reconciliation rule, they were really just trying to establish a standardized budget process, something the U.S. government lacked for most of its history. (Until then, Congress would basically pass tax and spending laws throughout the year willy-nilly, without any attempt to balance the books. Deficits ballooned as a result.)

The Congressional Budget Act of 1974 was approved with almost no opposition and signed into law by Richard Nixon, and it was intended to finally give lawmakers a timeline they could follow to pass a budget resolution annually.

Actually, the law originally called for lawmakers to pass two budget resolutions each year: one in the spring (which would be advisory) and one in the fall (which would be binding). But, of course, it was always possible that fiscal circumstances would change between the two resolutions. The reconciliation process was conceived as a way to smooth out any differences between the first advisory budget resolution and the second binding resolution.

Since the 1970s lawmakers knew they’d already be deliberating over two separate budgets, they figured they wouldn’t need a lot of time to discuss the reconciliation measures. So on just this one bill, they added a hard 20-hour limit on debate, which allowed it to be fast-tracked.

Without even realizing it, members of Congress had just handed their future legislative descendants a powerful secret weapon.

The budget process went on like this for a few years — but eventually, Congress got tired of having to pass two budget resolutions each year. (After all, lawmakers can often barely even agree on one!)

In 1985, the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act eliminated the requirement to have the advisory budget and the binding budget, but kept the reconciliation provision, even though the lack of a second budget resolution meant there really wasn’t anything left to reconcile.

It didn’t take long for presidents to catch on to the implications of that decision; the first was Ronald Reagan, who used the filibuster-free reconciliation process as a way to fast-track a series of spending cuts.

But, eventually, presidents began to think even bigger. In 2001, under George W. Bush, Republicans used reconciliation to push through a package of tax cuts. For the first time, a process set up to help keep the deficit under control was used to add to it.

From there, all bets were off: both parties began using the reconciliation process to advance all sorts of policy priorities, even in ways that padded the deficit (increasing spending for Democrats, cutting taxes for Republicans).

While other pieces of legislation need 60 votes — which generally requires working across party lines — using reconciliation means that parties in control of the White House, House, and Senate (even with slim majorities) are able to get through at least one big piece of legislation each year, without even consulting the other party.

In a polarized era, that pretty much guarantees that a president’s biggest accomplishments will end up going through the reconciliation process: that was true for Barack Obama (parts of the Affordable Care Act were approved by reconciliation) and for Donald Trump (his 2017 tax cuts used it too).

Under Joe Biden, Democrats used reconciliation to pass a $1.9 trillion Covid stimulus bill and the $900 billion Inflation Reduction Act, which tackled everything from drug prices to climate change.

Trump tried to repeal Obamacare using reconciliation, but was unable to marshal enough Republican support to do so. (Do you remember the late night moment when John McCain, who was the deciding vote and battling brain cancer, dramatically lifted his arm in a thumbs-down, ending his party’s hopes of repealing Obamacare?)

A Dunk in the Byrd Bath

To be clear, there are limits to what a party can do using reconciliation.

Back in the 1980’s, Robert Byrd — who represented West Virginia in the Senate for 51 years, the longest tenure of any senator in history — was one of the first Senators to recognize that reconciliation was growing far beyond what its creators had intended. “It was never foreseen that the Budget Reform Act would be used in that way,” he said.

Byrd argued that any “extraneous” provisions shouldn’t be allowed in reconciliation bills if they don’t impact spending or revenue (or if the spending or revenue changes are “merely incidental”). Congress passed the “Byrd Rule,” which gave the Senate Parliamentarian the task of deciding which provisions may comply with the rule.

In other words, anything in a reconciliation package better spend money or cut taxes. Every provision must relate to the budget. You can’t just add in a statement like, “And oh yeah, now all classrooms need to contain the holy book of _______ religion.” That’s not a budget bill.

The Parliamentarian is sometimes referred to as the Senate Referee. They pore over legislation and Congressional procedures, offering non-binding advisory opinions on whether procedures harmonize with rules and precedents.

When the Parliamentarian is analyzing reconciliation bills to confirm whether they follow the Byrd Rule, Congressional veterans refer to the legislation as going through the “Byrd bath.”

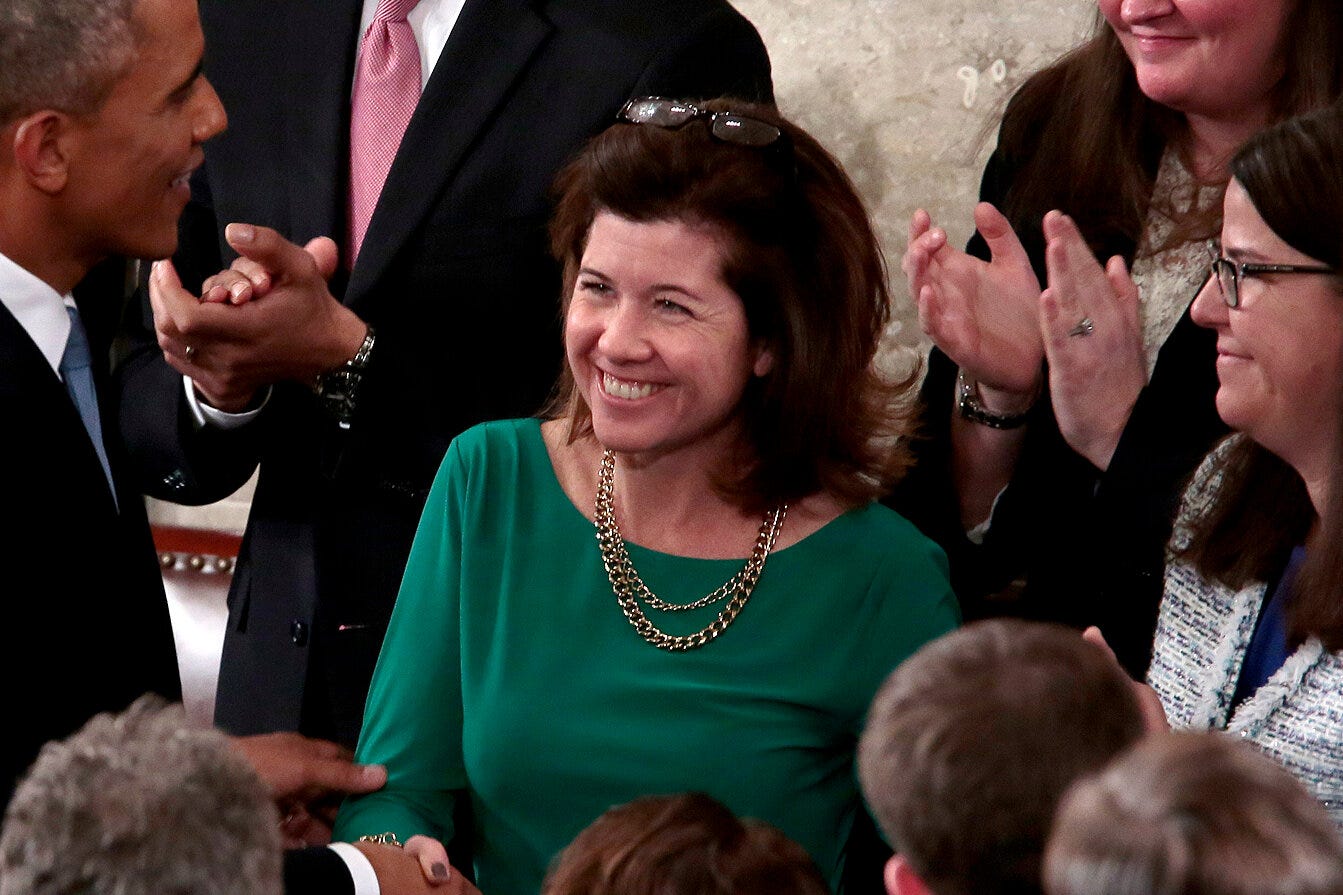

For example, in 2021, Democratic attempts to change immigration law and raise the minimum wage through reconciliation didn’t survive the “Byrd bath,” when current Senate Parliamentarian Elizabeth MacDonough ruled that their budgetary impacts were “merely incidental.”

However, the Byrd Rule is less hard-and-fast than you might think. 60 senators can vote to overturn a ruling of the Parliamentarian. Technically, the Vice President (who presides over the Senate) can do so as well, although that hasn’t been done in several decades.

Or, if they really want to make a statement, the Senate Majority Leader can even fire the Parliamentarian. That happened back in 2001, when Senate Republicans were unhappy with some of the Parliamentarian's rulings.

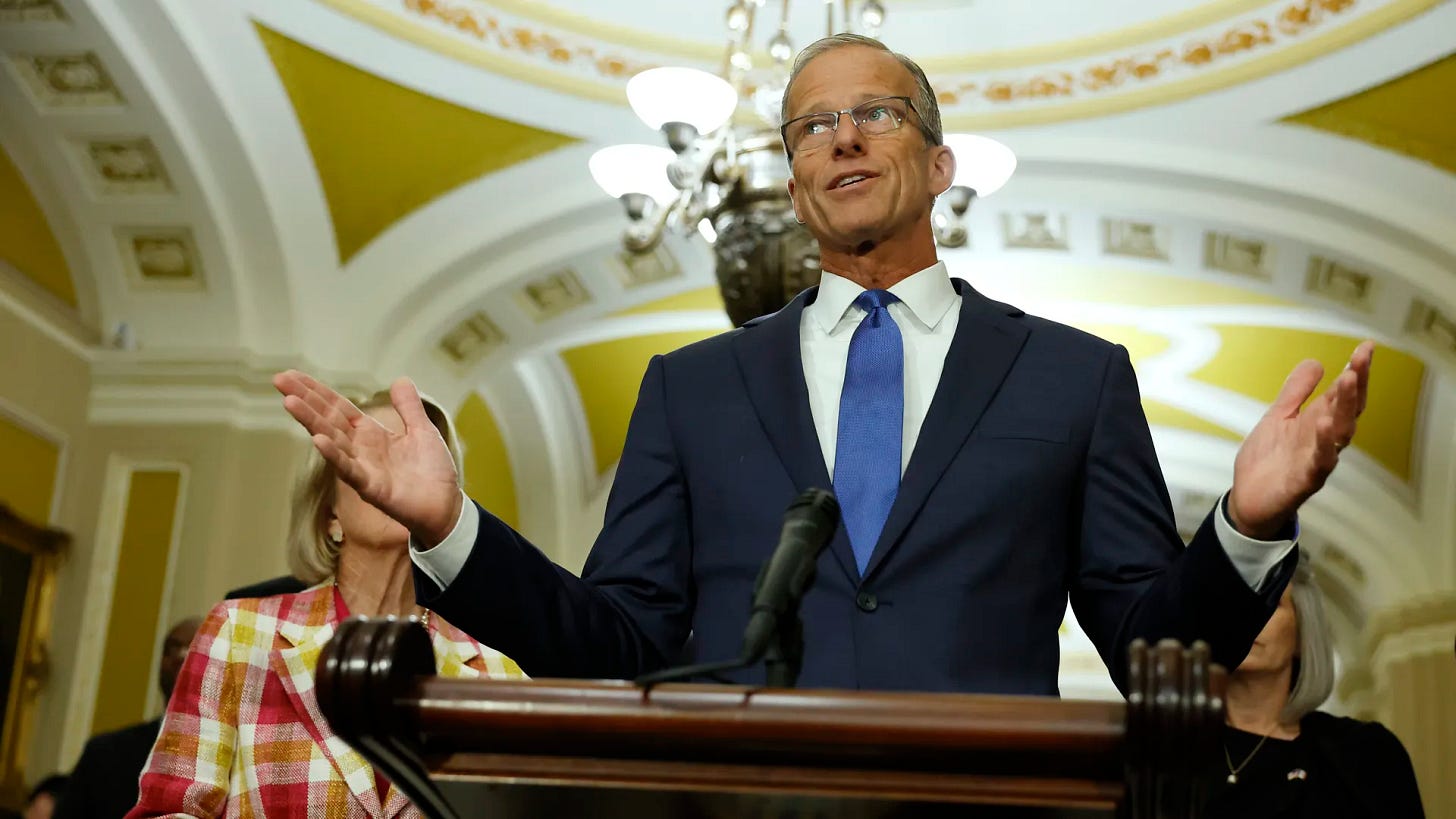

There’s good reason to think these sorts of clashes could heat up again in January — potentially even including calls for Vice President-elect JD Vance to overrule the Parliamentarian or for incoming Senate Majority Leader John Thune to fire her. That’s because some Republicans are pushing for a reconciliation package that includes immigration changes, the same issue that got Democrats in Byrd Rule trouble in 2021.

In general, some splits have emerged among Republicans about how to use reconciliation once they take power in Washington next month. Thune has called for the GOP to pursue two reconciliation bills next year: first, a package tackling the border; then, a package extending Trump’s 2017 tax cuts, many of which are set to expire in 2025. (Technically, parties can pursue up to two reconciliation bills per year if one wasn’t passed the year before.)

But Rep. Jason Smith, the Republican chairman of the influential Ways and Means Committee (which oversees budget issues, taxes, and things like Social Security and Medicare), has called that a “reckless” idea. He wants to focus on the tax cuts first.

President-elect Trump has yet to weigh in on this debate. Ultimately, Republicans will likely pursue whichever strategy he favors — but, no matter which path he takes, the early months of his presidency will be dominated by talk of reconciliation packages and debates about what can be done under the Byrd rule.

Accidents of History

There’s reconciliation, a footnote that became a weapon. But there’s also the fact that reconciliation is only influential because it evades the filibuster, which some historians believe was itself created by mistake.

Another factor that often looms large in Washington spending debates is the threat of government shutdowns; those only exist because of a 1980 memo by Benjamin Civiletti, Jimmy Carter’s Attorney General, who — like the fathers of reconciliation — didn’t set out to create the monster he unleashed.

“I couldn’t have ever imagined these shutdowns would last this long of a time and would be used as a political gambit,” Civiletti told the Washington Post in 2019, adding that the precedent he set had been “used in ways that were not imagined at the time.”

In 1974, Congress set out to regulate the budget process and get deficits under control. But since then, deficits have only climbed — reaching $1.8 trillion last fiscal year — and lawmakers have almost always missed the Budget Act’s deadlines, leading to last-minute brinkmanship and sometimes shutdowns.

But one legacy of the 1974 reforms has not only remained intact, but grown in influence: the reconciliation process, which has been responsible for shaping some of the largest legislative initiatives in memory, despite originally entering into the world as a mere afterthought.

Now when you hear it mentioned in the coming months, you’ll know exactly what they’re talking about.

Gabe's analysis of reconciliation highlights (yet again) a fundamental truth about Congress: the very people who benefit from a broken system are the ones we expect to fix it. Or maybe "expect" isn't the right word... we know it will never change. Are we supposed to just accept this as unchangeable?

It was a parenthetical note that Gabe made, but take Senator Robert Byrd's 51-year Senate career as an example. While Americans broadly agree that such lengthy tenures create problematic power dynamics and stagnation, we've somehow normalized the idea that Senators can serve unlimited terms. You'd think the same logic that created term limits for presidents would apply here. However, the only way to change this would be via Congress, also known as never going to happen. (Some history about how we almost had Congressional term limits can be read here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S._Term_Limits,_Inc._v._Thornton)

Examples of Congressional perverse incentives are numerous. The rules that govern Congress are largely set by Congress itself – a clear conflict of interest that would be unacceptable in any other context. Imagine if professional athletes served as their own referees during games, or if restaurant inspectors were chosen by the restaurants they inspect. We would immediately recognize such arrangements as fundamentally flawed, yet we've accepted this exact scenario in our highest legislative body.

I mentioned this recently in a comment on one of Sharon's pieces, and I'll repeat it again here because it's relevant and important. Her proposals for improving elections, and thereby repairing the perverse incentives that Congress operates under, can be found here: https://thepreamble.com/p/my-proposal-to-improve-elections

Her call for citizen oversight groups to establish congressional rules and ethics standards addresses this exact problem. As she points out, we need external mechanisms to implement reforms that Congress will never voluntarily adopt. Term limits, age limits, campaign finance reform... these changes won't come from within the system.

I'm working to build a coalition focused on creating the external pressure needed for these reforms. Politicians are trapped in a prisoner's dilemma where they can't support reforms without risking their careers – or more accurately, they can't support reforms when the current system benefits their side, though they're quick to demand changes when the tables turn electorally. Many of them are already begging us to save them from themselves. We need to create conditions where they can collectively agree to limit their power.

If you're frustrated by these institutional failures and want to help create practical solutions, I'd love to connect. We need people who understand policy mechanics and human psychology to design reforms that can actually work in the real world... sure, that would be very helpful. But we also need people who might not understand everything, yet are passionate about fixing the problem. I'm probably closer to the latter: I am not an expert, but I can see that things need to change, and I can see that they never will change without thinking outside of the box.

Who else wants to help tackle this challenge? Reply here or shoot me a message if you'd like to join our discussion group on making these reforms reality. We're particularly interested in exploring ways to build public pressure for constitutional amendments and state-led initiatives.

I read the headline and I just wanted to crawl back into bed. I’m having a hard time dealing with this reality.