How to Beat the Speaker of the House

Together with:

Congresswoman Mary Norton wasn’t your typical lawmaker in 1930s Washington.

“To snooty Washington society she is a business school graduate, a [machine politician], and a Catholic and hence unacceptable,” one journalist wrote.

There was also one more thing: she was a “she.” When Norton arrived as a New Jersey representative in 1925, there were 531 members of Congress: 528 men, and three women. Of the trio, Norton was the only one who hadn’t been elected to succeed a deceased husband; she was also the only Democrat. In fact, until Norton, no Democratic woman had ever been elected to the US House of Representatives.

Her integration into Washington wasn’t always smooth. Once, when a colleague called her a “lady” on the House floor, she shot back: “I am no lady, I’m a member of Congress, and I’ll proceed on that basis.” Later, when Norton became the first woman to chair a major congressional committee, another of her male colleagues took exception. “This is the first time in my life I have been controlled by a woman,” he said.

“It’s the first time I’ve had the privilege of presiding over a body of men,” Norton replied, “and I rather like the prospect.”

Plenty of people in Washington know policy. But the people who really get stuff done are the ones who also understand procedure, who take the time to learn how Congress works and how to make it work for their agendas. The people who learn how to get around obstacles and turn their proposals into reality. “I’ll let you write the substance,” the late Congressman John Dingell liked to say. “You let me write the procedure, and I’ll screw you every time.”

Mary Norton knew that lesson and deployed it expertly in the biggest fight of her career: the battle over the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which set the first federal minimum wage in American history.

Franklin D. Roosevelt had promised to create a minimum wage in his 1936 campaign, but legislation to that effect had stalled in Congress. Then, as now, bills generally didn’t reach the House floor unless the powerful Rules Committee signed off. The problem was, the panel was controlled by a coalition of southern Democrats and conservative Republicans, who joined forces to block the minimum wage bill (just as they would later do with civil rights measures).

As chair of the Labor Committee at the time, Norton was the FLSA’s chief advocate. She didn’t let the Rules Committee blockade stop her. She used her knowledge of the House rules to find another way to get her bill across the finish line.

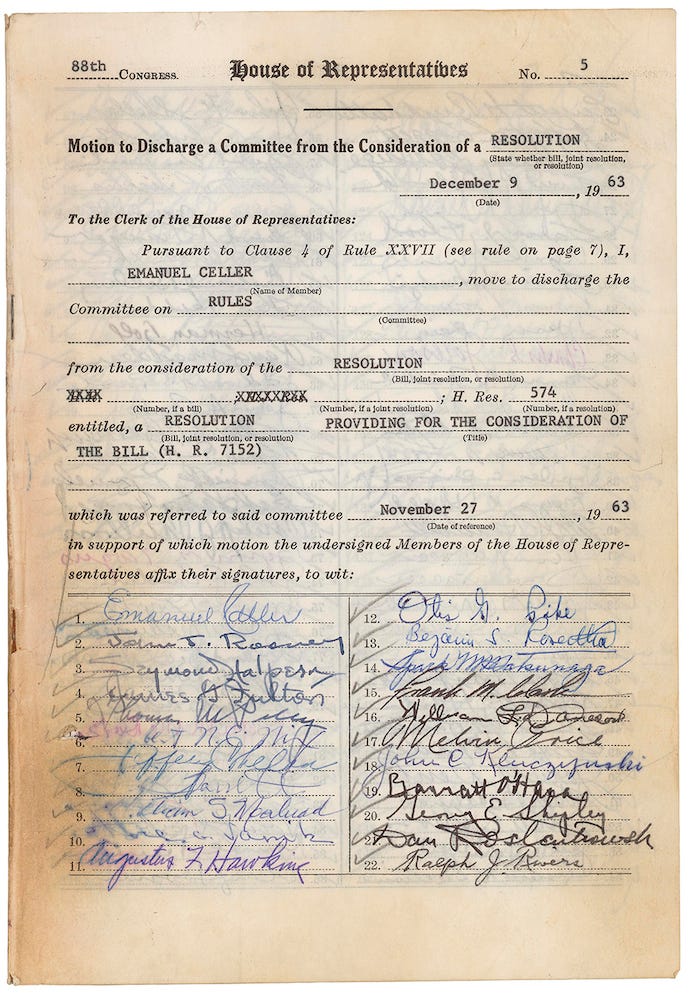

In order to make minimum wage a reality for working Americans, Norton used an obscure procedural tool known as a discharge petition.

Discharge petitions are a last-ditch option for lawmakers to force a bill of theirs onto the House floor. If a majority of House members — 218 in total — sign on to the petition, a bill is guaranteed a vote, even if the Rules Committee (and, by extension, the House speaker, who usually controls the panel) is opposed. It’s the best tool rank-and-file members have to assert their agendas; when they’re successful, it’s usually because of bipartisan coalitions who add their names in defiance of Congress’s top leaders.

The discharge petition was created in 1910, as a way for House members to combat the power of then–Speaker Joe Cannon, who ruled Congress with such an iron fist that he was known as “Czar Cannon.”

But almost three decades later, when Norton drafted a discharge petition to advance the minimum wage measure, no bill had ever become a law using the little-known process.

Norton went about lobbying her colleagues, determined to end that dry spell. By the time she was ready to walk her petition onto the House floor — with her name as the first signature — it was clear Norton’s persistent advocacy had paid off.

So many House members crowded around the petition that the speaker of the House had to beg them to form a single-file line. Congressmen jostled with each other to get to the front; Norton handed each one her fountain pen when it was their turn. Up to that point, no discharge petition had ever received more than 100 signatures in a single day. In less than two and a half hours, Norton notched all 218 she needed.

The Fair Labor Standards Act quickly became law, enshrining not only the country’s first minimum wage ($0.25 an hour), but also a 40-hour work week (with guaranteed overtime pay) and a ban on “oppressive” child labor. Norton would later call it her proudest achievement as a congresswoman. She didn’t earn the nickname “Fighting Mary” for nothing.

Norton’s success during the minimum wage debate was the result of careful planning — including recruiting a powerful ally. Using her relationship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Norton wrote a telegram to FDR, pointedly reminding him of his past promises to support a minimum wage and asking him to nudge anxious Democrats towards the discharge petition.

In his response, Roosevelt acknowledged the important role committees play in filtering legislation. “There are, however, certain types of measures in each session which are of undoubted national importance because they relate to major policies of government and affect the lives of millions of people,” he added.

“It has always seemed to me that in the case of these measures — few in number in any one session — the whole membership of the legislative body should be given full and free opportunity to discuss them,” Roosevelt wrote.

From Ground News:

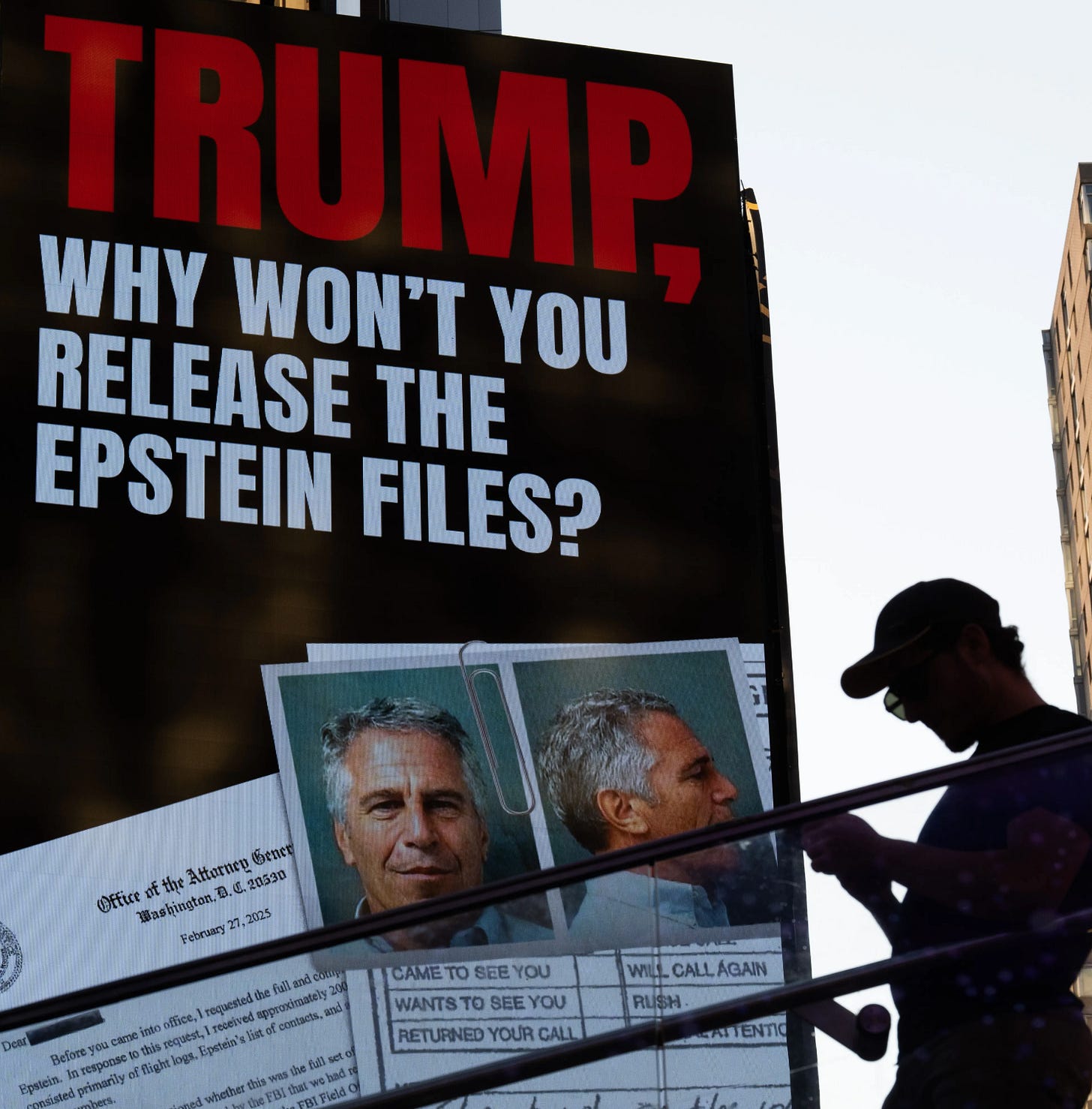

The drama and heightened scrutiny surrounding the release of the Epstein Files won't be going away anytime soon. As the House Committee on Oversight issues a subpoena to the Justice Department, Speaker Mike Johnson finds himself caught between demands from the White House and pressure from members of his own party. But depending on where you get your news, your understanding of what the files contain may vary. With over 80 sources covering this story, Ground News is the most practical solution to exposing spin before we mistake it for fact.

If you like The Preamble, you’ll love their app and website. It pulls in every perspective on the most polarizing issues then breaks down each source’s political bias, factuality, and ownership so you understand news isn’t just reported – it’s crafted.

Their Blindspot Feed even exposes how much our perspective is shaped by selective reporting from partisan outlets we mistake as “unbiased.” Ground News is independent and funded by readers like us. But my readers get 40% off the same unlimited access Vantage plan I use.

Subscribe now at ground.news/preamble for $5/month.

Discharge petitions were a break-glass-in-case-of-emergency option, he argued, only to be used to force a debate when an issue absolutely demanded it.

In the decades since, House members mostly haven’t followed in Norton’s footsteps, opting to obey orders from their party leaders instead of rocking the boat and pushing for their bills to get a vote.

But, in the last two years, with votes being scheduled on fewer and fewer issues that “affect the lives of millions of people,” rank-and-file lawmakers are increasingly taking matters into their own hands.

Three discharge petitions have successfully obtained 218 signatures in the last two years, more than in the preceding 30 years combined.

The first was for the Federal Disaster Tax Relief Act, which provided tax relief to the victims of natural disasters. The second was for the Social Security Fairness Act, which increased Social Security benefits for millions of retired teachers, firefighters, police officers, and other public workers.

Both were bipartisan bills ultimately signed into law by President Biden.

The third was for a House rules change that would have allowed new members who had just given birth to vote remotely. The petition got to 218, but its backers reached a deal with House Speaker Mike Johnson to enact a modified version of the proposal instead of forcing a vote.

All three discharge petitions represented a rare loss of control for Johnson, who normally sets the House floor schedule as speaker. Enough of his own members felt so strongly about those bills that they went around him, deciding that the issues at hand were more important than party unity.

Get ready for even more discharge petitions this fall.

Johnson recessed the House early last month partially to avoid being forced into a vote on a bipartisan bill to require the Justice Department to release the Jeffrey Epstein files.

The bill’s authors, Reps. Thomas Massie (R-KY) and Ro Khanna (D-CA), have said they will introduce a discharge petition when the House returns in September. If the petition receives 218 signatures, Democrats and Republicans will be able to team up to force a vote on Epstein, against the Trump administration’s wishes.

Rep. Anna Paulina Luna (R-FL), who was behind the remote voting petition, also plans to unveil a high-profile discharge petition once members return from recess. Luna’s petition would trigger a vote on the End Congressional Stock Trading Act, which would ban members of Congress, their spouses, and their dependent children from trading and owning stocks during their service in Washington.

Both of these bills share many of the features of successful discharge petitions.

Discharge petitions generally come into play when an issue is (a) widely popular across party lines, but (b) would harm an entrenched interest, leading congressional leaders to oppose it.

The Fair Labor Standards Act, for example, was supported by 67% of Americans in its time. But corporate titans with influence over both parties opposed the measure, tying up the bill until Norton’s discharge petition dislodged it.

Similarly, 79% of Americans want the Epstein files to be released. But because the documents could embarrass Donald Trump, Speaker Johnson has refused to set a vote. That leaves a discharge petition as the best way to force movement on the issue.

Discharge petitions are also often an effective way to enact reforms to Congress itself, by going around party leaders and other longtime incumbents who might be harmed by changes to the status quo. The last major campaign-finance reform package, the 2002 law known as McCain-Feingold — which sought to limit the role of money in politics and is also the reason why politicians have to show their face and tell you they “approve this message” in every ad — became law because of a discharge petition.

The proposal to ban congressional stock trading, supported by 86% of the public but opposed by career pols on both sides of the aisle, would fit comfortably in this lineage.

Even when discharge petitions don’t reach 218 signatures, they can play a key role in pressuring congressional leaders to call a vote on important pieces of legislation. That’s what happened with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which made it out of the Rules Committee only after the panel’s chair was persuaded that scheduling a vote would be less embarrassing than being outnumbered on a discharge petition that had been filed.

Every member of Congress has been elected to represent their constituents, but more often than not, they are content to follow the whims of their party leaders, even if it means ignoring issues their voters want addressed.

But discharge petitions offer these members a tool to force their will, as long as they’re bold enough to take a stand.

Mary Norton was, and that’s why we have a national minimum wage today. When Congress returns next month, some key lawmakers are set to follow in her example. Votes could end up being forced on two of Washington’s most contentious issues as a result.

More stories like this, please! Small and mighty and hopeful and a dash of current events for relevance and practical application. Love it.

What an amazing story. I feel guilty for not knowing anything about the first elected congresswoman and any of her accomplishments. Nor did I understand the way these discharge petitions worked, both logistically and politically. I’m gonna dedicate my morning to learning even more about Mary Norton. Thank you, Gabe!