How Religious is the US Compared to Other Countries?

It depends on what you mean by “religious.”

One of the more reliable findings in the social science research on religion is that Americans, on average, tend to be more religious than people in other developed democracies, from Europe to Canada to Japan. Yet we are markedly less religious than pretty much the rest of the world, including many non-democracies, not-so-developed countries, and most of the Global South.

Why do we occupy this strange middle ground?

To solve this mystery, we need to first get clear on what we mean by “religious,” which is one of those concepts that feel fairly straightforward at first (you probably have a pretty quick answer to the question “Are you religious?” right now) but are incredibly complicated once you start to pick it apart. In the process of doing so, I hope you’ll also see that working with data is often as much a philosophical exercise as it is a mathematical one.

How do we turn “religion” into a number?

One of the standard ways researchers have measured religiousness over the years is by asking the relatively simple question, “Is religion an important part of your daily life?” A nice thing about this approach is that it’s pretty universal — respondents can take religion to mean whatever they want and then share the extent to which their version of religion shows up in their lives. It’s also pleasantly specific for such a broad measure: we want to know if whatever you think of when you think of religion is something that shows up for you daily.

According to this measure, we see, indeed, that Americans are notably more religious than other developed democracies, typically defined as countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

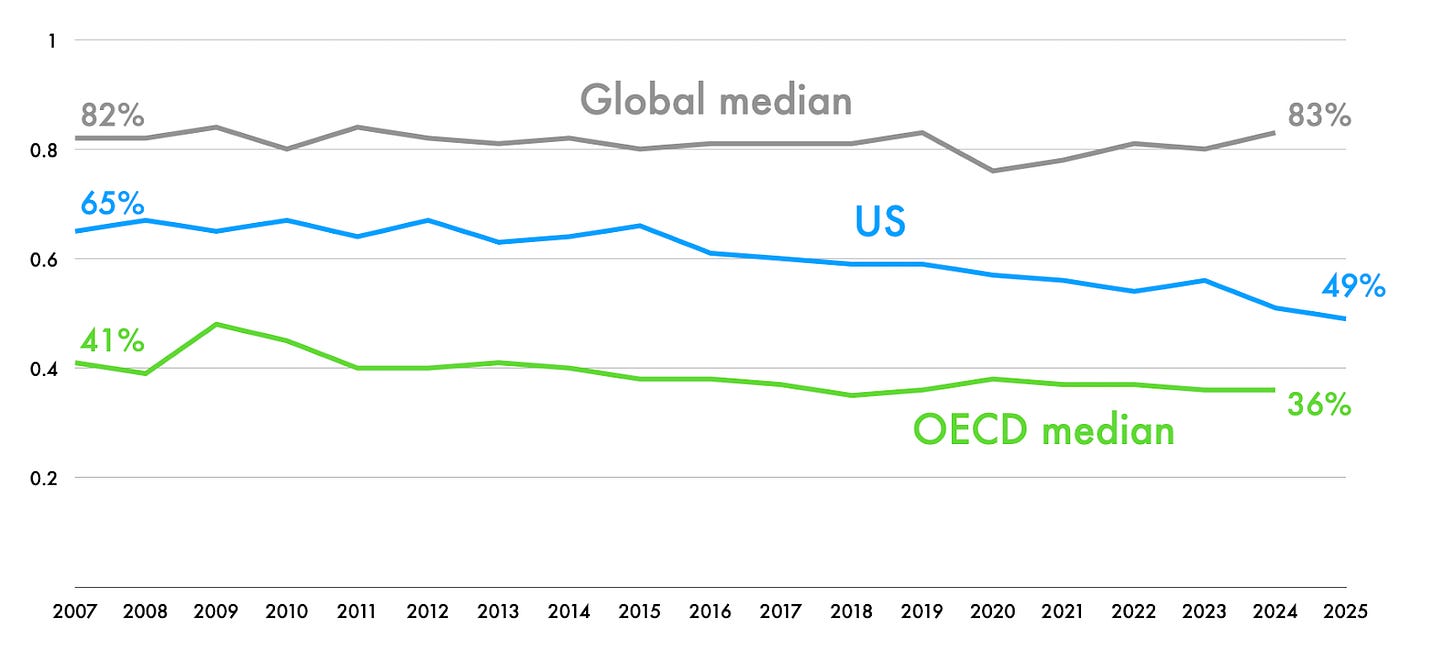

More Americans than people in other developed democracies consider religion to be an important part of their daily life

Percentage of respondents who answered yes to the question “Is religion an important part of your daily life?”

Two other things to note from this chart are that the gap between the US and other OECD countries is shrinking, largely driven by a decrease in religiousness (according to this measure) in the US over time, and that the global median has been relatively flat for decades.

But this is only one way we might think about religion. Another might be to focus on whether we consider ourselves to have an identity that is affiliated with a particular religion (even if we don’t practice it, or perhaps even believe its tenets). Or we might focus on behavior: regardless of your self-proclaimed identity or beliefs, do you act like someone who is religious? The next chart taps into some of those distinctions, again organized by OECD membership status.

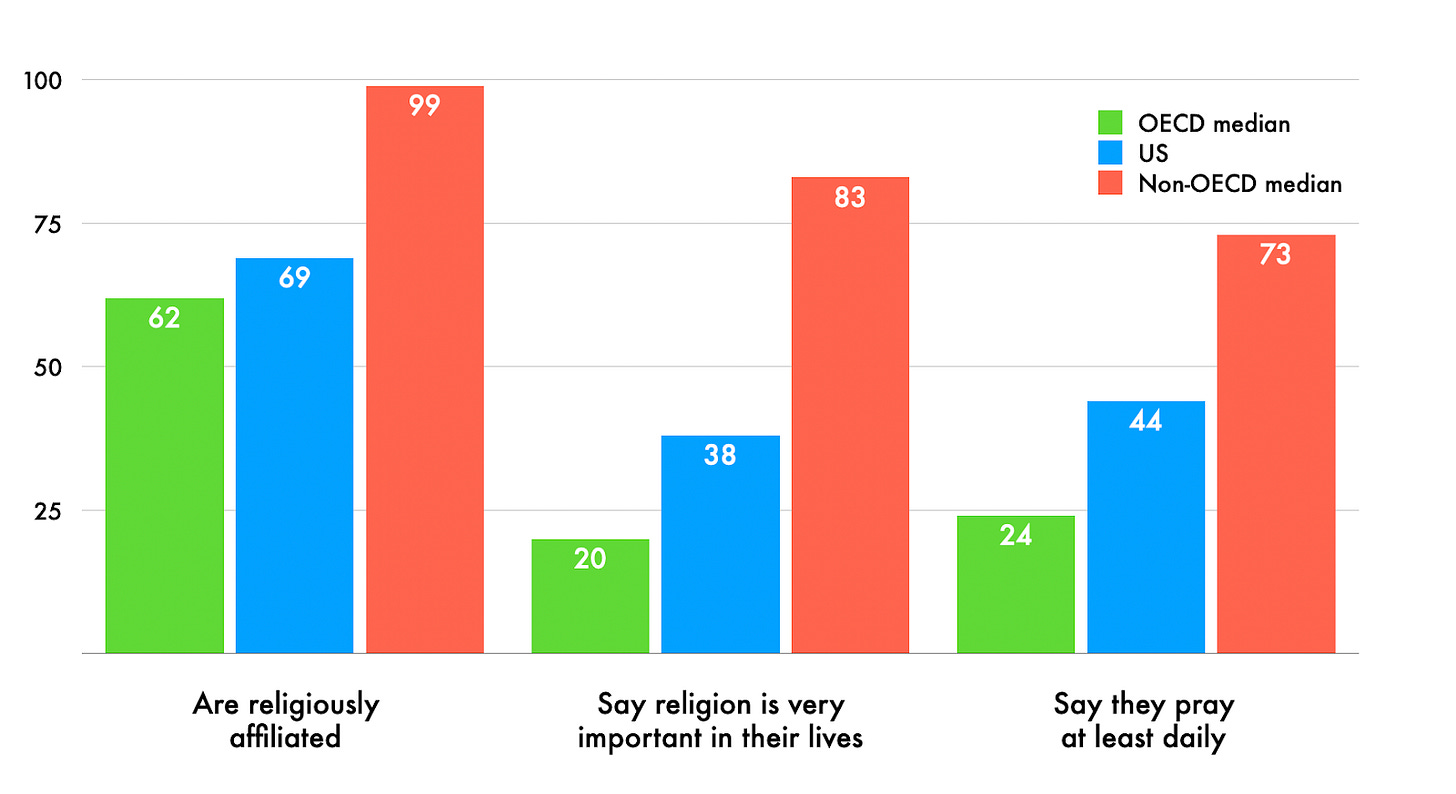

Americans are about as religiously affiliated as people in other developed countries

Percentage of respondents in the US compared with respondents in OECD and non-OECD countries who:

A very important caveat about the data from this chart is that it’s from a completely different study from the first chart from Gallup, which is conducted across more than 140 countries. This particular 2025 Pew study combines two surveys from 2023–24 to build a dataset of 36 countries, of which 20 are OECD and 16 are non-OECD. The smaller sample size doesn’t mean we necessarily take it less seriously — often smaller studies can allow for more nuance and detailed questions — but it does mean we need to use many grains of salt, and maybe some rosary beads for good measure, when we compare one study with the next.

Nevertheless, a few important things stand out. First, the cluster of bar charts on the left represent respondents who named a religion when asked, “What is your current religion, if any?” When we think about religion in terms of whether we consider ourselves affiliated with a religion, as opposed to whether it’s important in our daily lives, we look a lot more like the rest of the OECD.

The second cluster represents the percentage of respondents who indicated that religion was very important in their lives. Here is where we start to see the US back in the middle zone. You’ll also notice that the percentage of respondents in the US who say religion is important in their lives (38%) is lower than the percentage in the Gallup survey from the first chart (49%). These differences likely reflect a few things: the Pew survey includes only whether religion is “very” important as opposed to “important”; it doesn’t ask about importance in “daily” life; and the preceding questions, which can influence later answers, were different. We’re really swimming in salt grains now!

The third cluster considers a more behavioral interpretation of religion. Again we see the US in its middle ground, with almost half of us stating we pray daily (though one wonders about a kind of response bias in which people are more likely to answer affirmatively to a question about something that might be perceived as a desirable thing to do).

What about spirituality?

What if you set aside any formal religious classification or identity, and maybe even ditch the charged word “religious” altogether? This third chart is thus officially dedicated to the hippie, New Age, and forest girl–identifying readers of The Preamble.

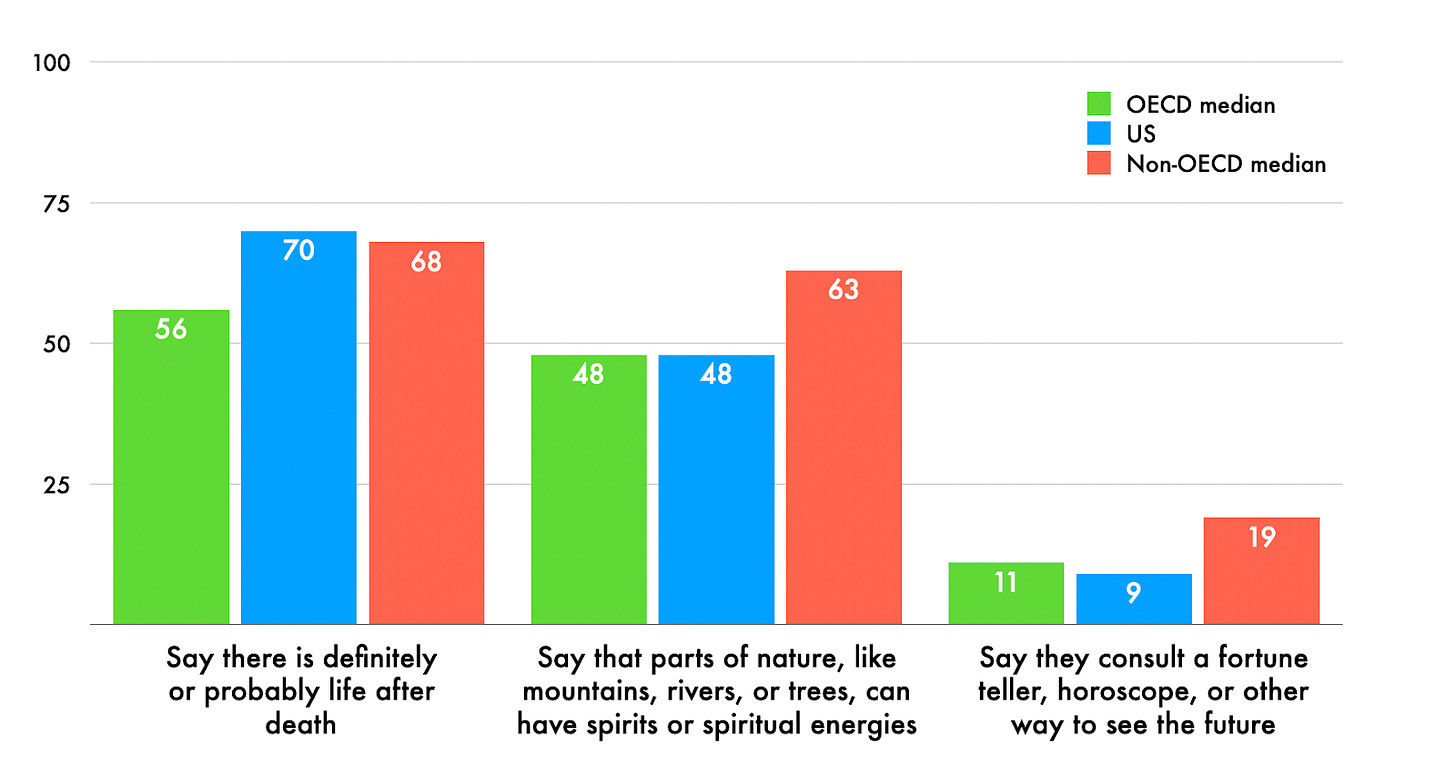

People everywhere are similarly spiritual

Percentage of respondents in the US compared with respondents in OECD and non-OECD countries who:

The striking headline from these charts is that we see a massive flattening in the differences between countries. If anything, the US nudges ever so slightly ahead of both the OECD and non-OECD median scores on whether there is an afterlife (I assume heaven is thus one giant Fourth of July party), but overall levels of spirituality are remarkably comparable around the world in this survey. (By the way, there are many more fun questions asked in this survey, and I encourage you to explore them.)

Can we go deeper?

We’ve been talking about religion in fairly superficial forms, like whether people are affiliated with a religion or engage in specific religious activities. Luckily, we can probe a little further with a concept called “religious centrality.” This is a metric with roots in psychology and religious studies, and it’s focused on the idea that someone might be religious due to either intrinsic religious motivation or extrinsic religious motivation.

Someone is intrinsically religiously motivated if religion is truly part of their core belief system. They are extrinsically religiously motivated if they are religious for reasons that serve some other goal, such as social status or community membership. Religious centrality is a metric that attempts to get at this idea of intrinsic religiosity by asking whether religion is the core guiding principle in someone’s life (upping the ante from whether religion is simply “important” in daily life).

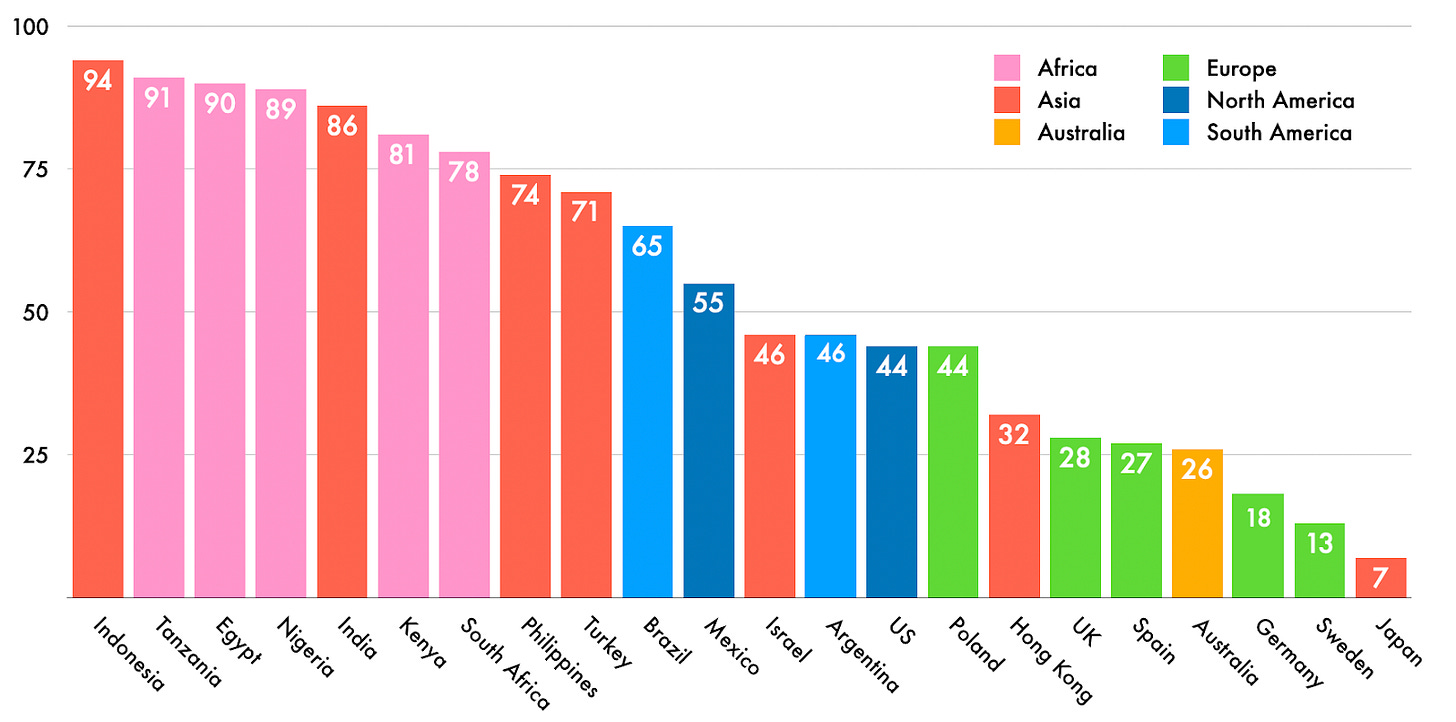

Our religious centrality rates are similar to those in Poland, Israel, and Argentina

Proportion of respondents in each country who agreed with the statement “My religious beliefs and practices are what really lie behind my whole approach to life.”

The above chart presents data from a recent study that was also notably the first to attempt to quantify religious centrality across a religiously diverse range of countries (most prior work focused on the US and Europe).

A few things stand out. First, religion plays a really central role for a lot of people in many parts of Asia and Africa. Second, the US is still more religious than much of the OECD on this metric. But, third, it is about as religious as a number of perhaps surprising countries: Poland, Israel, and some of our neighbors in the Americas.

Before we read too much into this, however, note that the study, like the Pew one above, is not representative of the entire world. We are leaving out a lot of countries, including China and much of the Middle East. While there is impressive survey work being done across those other countries, we don’t yet have enough cross-national measures on detailed religious questions to feel confident making comparisons, even with all the salt in the world.

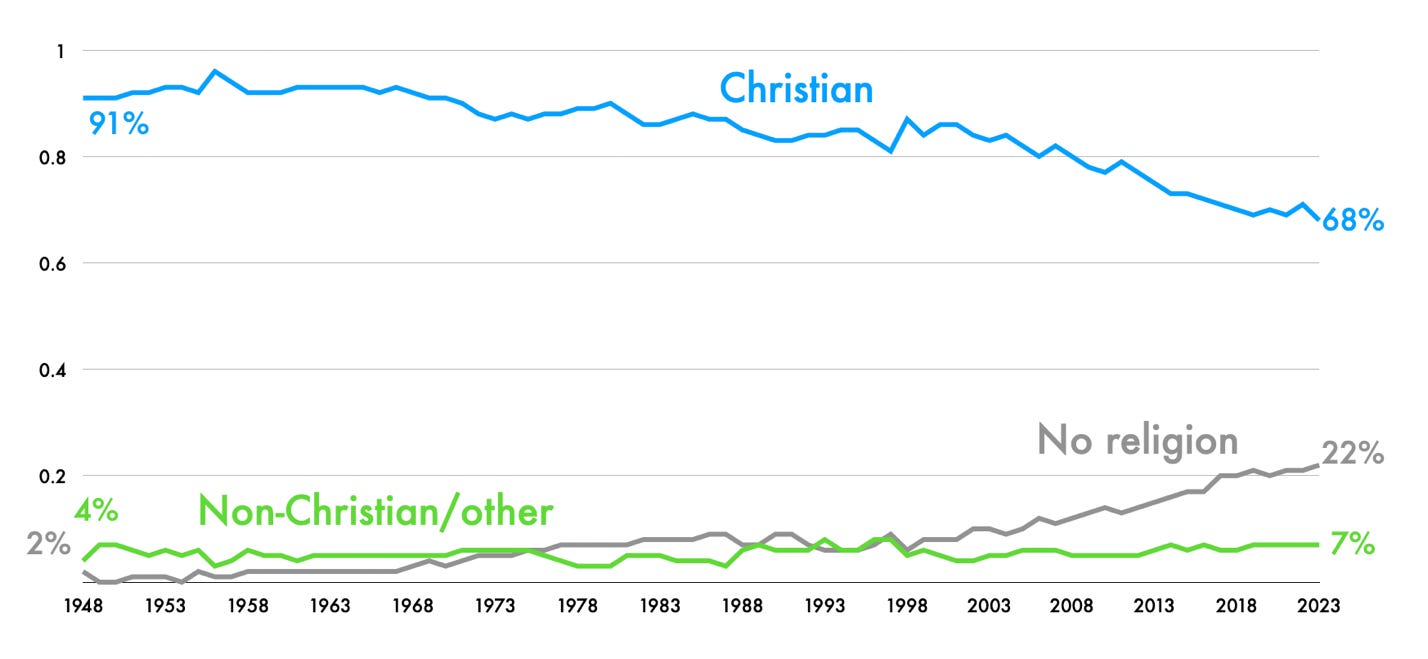

To put all these pieces together, we have one more (sacred) stone to turn over. We need to return to the observation in the first chart that religiousness, measured as the importance of religion in our daily lives, seems to be on the decline in the US. A similar pattern arises when we ask Americans whether they identify with a specific religious faith (yet another slightly different way to ask about religiousness).

The proportion of Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated is on the rise

Percentage of respondents in the US who indicate they identify with a specific religious faith

Notably, the decline in Christianity in the US seems to be much less about the rise of other religions than about the rise of people who simply say they have no religious preference. Also importantly, “no religious preference” does not necessarily mean “atheist.”

In fact, among the religiously unaffiliated in yet another Pew study, only about 17% of “unaffiliated” respondents identified as atheists, while 21% indicated they are agnostic, and the remaining 66% simply identified as “nothing in particular.” So the decline in Christianity may not be a result of less religiousness per se, but of a loss of formal or more traditional religion.

Won’t someone think of the religiously unaffiliated?

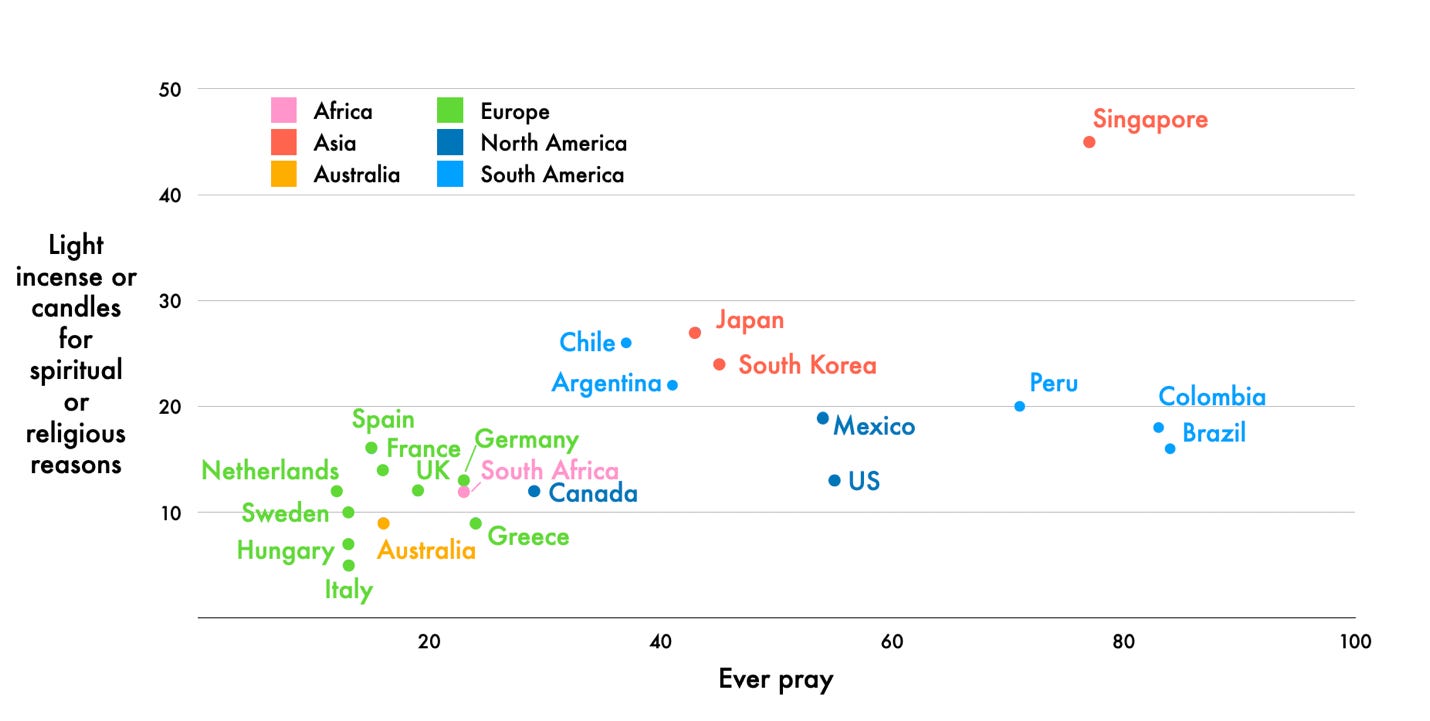

This brings us to our final, and perhaps most wild (if I may say so), chart of the article. It shows, in my opinion, two pretty fun religious behaviors among religiously unaffiliated people in 22 countries (not the same 22 as in the religious centrality measure from above, just an auspicious number).

Many religiously unaffiliated Americans are still fairly religious

Percentage of religiously unaffiliated respondents in 22 countries who indicate they ever “pray” (x-axis) or “light incense or candles for spiritual or religious reasons” (y-axis)

According to this chart, 55% of religiously unaffiliated Americans say they ever pray, and 13% ever light incense or candles for spiritual or religious reasons. This puts us in the ballpark of some of the other countries in the Americas on these two questions, and again pulls us away from Europe. Japan, which scored the lowest in the world on religious centrality, has a fair amount of prayer and candles among their religiously unaffiliated.

What have we learned?

Putting all the pieces together paints a complex and evolving picture of religion in the US. When it comes to how important we perceive religion to be in our daily lives, we outpace the rest of the OECD by a fair margin, though the gap has been shrinking in recent years. But if we think of religion as more of an external identity or label, we are nearly indistinguishable from many of our OECD peers — and we are all far less religious than the rest of the world. And people in America are pretty much just as spiritual as people everywhere.

Additionally, the newer cross-national measure of religious centrality offers more granular clues about where we land compared with other countries. Just under half of Americans consider religion to be a guiding force in our lives, and we are remarkably similar to countries across three different continents, even in just a small sample of countries. But even people in the US who are religiously unaffiliated report participating in religious activities, like prayer and lighting candles.

Religion is of course complex, personal, and individual. Yet, we can also identify striking trends around the world, depending on how we think about the many ways religion might show up in someone’s life.

Okay, but why are we like this?

About ten billion tomes have been written about why the US has the religious patterns it does, and making causal claims from observational and historical data like this requires pretty much all the salt in the universe.

With these (massive) caveats, a prevailing narrative is that because the US has no established religion, and was in some areas colonized by Europeans looking for a place to practice their religion freely, churches had to compete in a kind of spiritual marketplace for people to join them. This meant that churches in the US worked hard to attract and retain more “customers” by adapting services, beliefs, and even moral codes to stay relevant and appealing. This also meant that if we “customers” didn’t like a particular church, rather than leaving religion entirely, we could simply switch to a new one. As Anna Grzymala-Busse describes it, “religious pluralism thus breeds religious fervor.”

As to why other parts of the world are more religious than we are, the simplest story comes from modernization theory, which used to hold that as countries developed they would become more secular. But the fact that many countries, including the US, have developed economically and yet remain religious suggests a flaw in this logic.

Instead, another argument has arisen, which is that religion becomes attractive whenever individuals face existential insecurity, or a feeling that basic survival cannot be taken for granted. Thus, religion is especially important among vulnerable populations, whether they are in a developing country or even in parts of the US, given the lack of a welfare state here akin to those in much of the rest of the OECD.

Finally, it’s debated whether the US is indeed becoming less religious. You’ll find strong arguments on either side, but much of the evidence in the charts here suggests that while we may be drifting away from formal religion, many of us are still quite religious and/or spiritual in our own ways. Though we still aren’t lighting nearly as many candles as people in Singapore.

One take-away for me is that there doesn't seem to be a connection between people in a country that claim that religion is central to their lives and the amount of peace, care, and concern for others that exists in those places. In fact, without studying the charts too closely, the inverse might be true.

Thank you for this great article. As I was cornered at our local farmers market yesterday by a young fellow wanting to ask me about the ‘true’ meaning of Christmas, I actually felt good after I blasted his intentions into oblivion. I simply told him that after 25 years of unraveling the damage of all the religious garbage, I am happy to be out of that fog and in a place where I can enjoy the holidays as simple moments to enjoy the love of family and friends.