How ICE Is Mimicking 19th Century Slave Patrols

Immigration enforcement agents are using methods that look very familiar

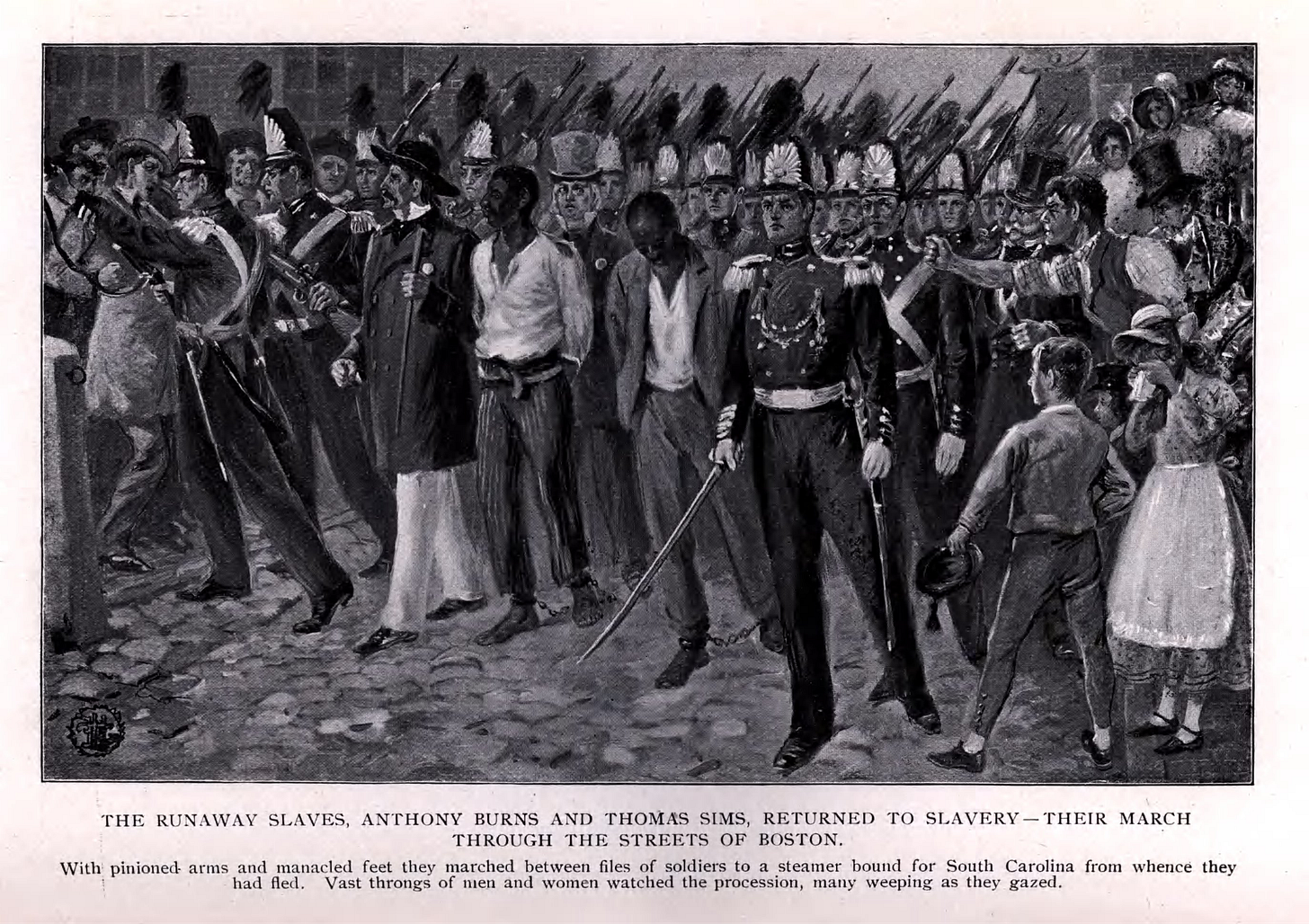

On June 2, 1854, the city of Boston was under military occupation. Federal troops with a loaded cannon stood ready as 1500 militiamen formed a human corridor from the courthouse to the harbor to march a single prisoner through the streets. His name was Anthony Burns, and he was a 20-year-old clothing store worker. His crime was escaping slavery.

Shortly after Burns was first captured and held pending a hearing to confirm he was a fugitive slave, a mob gathered at the courthouse and stormed the door in an attempt to rescue him. A brawl with law enforcement ensued. By the time more police appeared and ended the riot, a federal deputy was dead, and Burns remained captive.

Days later, as Burns was marched toward the harbor where he was to be loaded onto a ship and returned to slavery in Virginia, 50,000 people crowded the route in protest of his removal. Storefronts were draped in black. American flags hung upside down. Someone had suspended a coffin across State Street with one word painted on its side: Liberty. As soldiers beat back the crowd with bayonets, protesters shouted back at them: “Shame!”

Authorities managed to get Burns onto the ship, but the spectacle cost the federal government $40,000 and unprecedented manpower. It also backfired completely. Within months, Boston became a “no-go zone for slave catchers,” according to historian H. Robert Baker. Secret resistance networks formed, and Massachusetts passed laws that made federal enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act nearly impossible. No freedom seeker was ever captured in the state again.

Over the last few weeks, as agents from US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Border Patrol have flooded the streets of Minneapolis, snatching away residents and sending them to faraway detention camps — and even killing citizens — commentators have looked to history for comparisons, often reaching for World War II analogies that liken ICE to the secret police of Nazi Germany. But we needn’t look outside the US for the clearest parallel. ICE isn’t the Gestapo — ICE is the slave catcher. And the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 tells us everything we need to know about where this is heading.

A law designed to hunt

Before the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868, Black people in the United States were not considered citizens. As a Black person, if you were enslaved and left the domain of your enslaver, you were breaking the law. Unless you carried papers declaring your freedom or authorization for travel, you were, effectively, “undocumented,” and any undocumented Black person was subject to arrest and punishment.

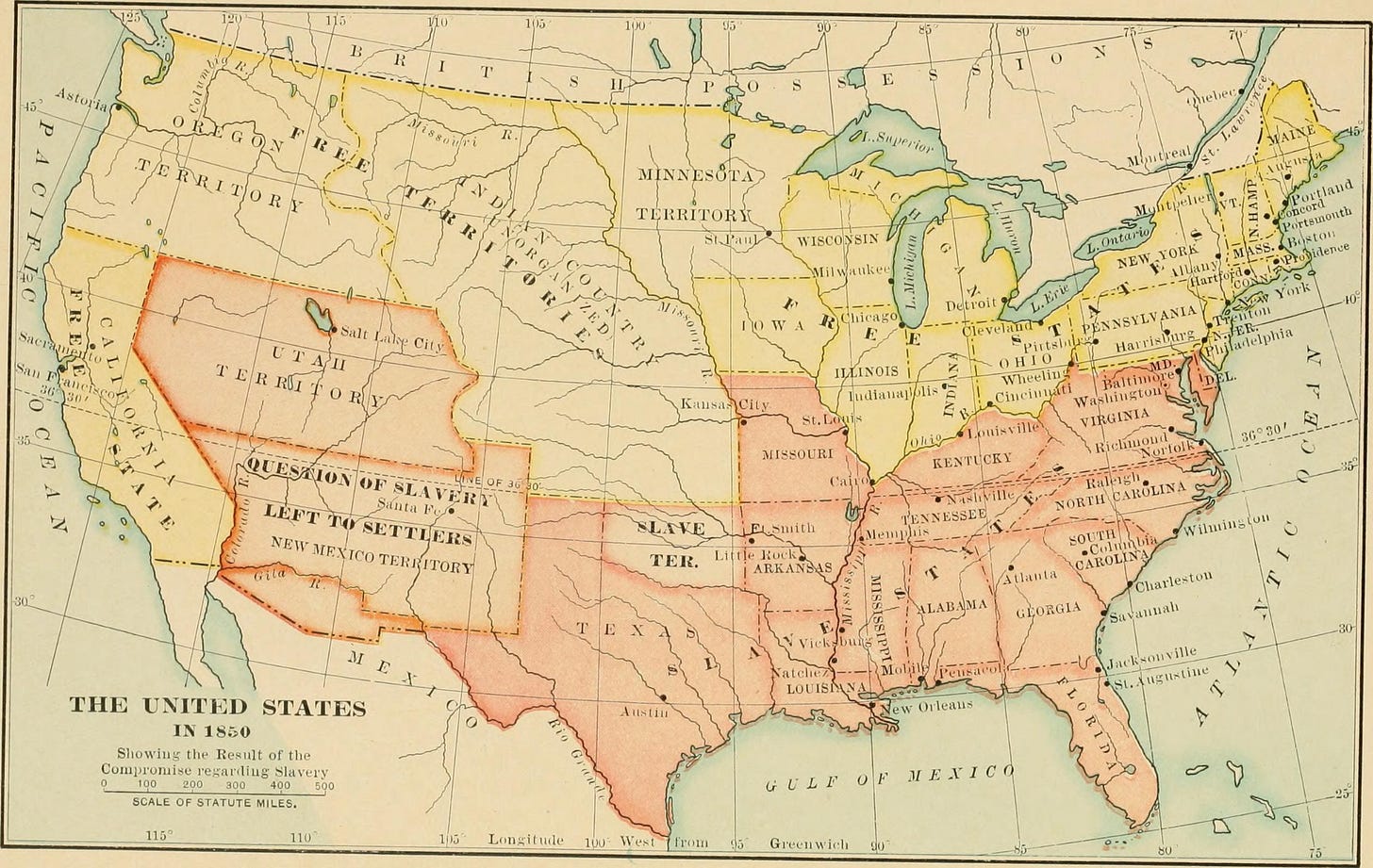

However, in the mid-1800s, the nationwide political balance began to shift in favor of Northern states. With California and New Mexico poised to enter the Union as non-slave states, the South’s grip on the Senate looked increasingly fragile. Fearing the introduction of laws that would favor the enslaved over the enslaver, Southern politicians warned that their states would leave the Union if their “property rights” weren’t protected. South Carolina’s John C. Calhoun openly threatened secession.

The resulting compromise, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, created one of the most aggressive federal enforcement regimes in American history. The new law didn’t simply allow slave owners to retrieve enslaved people who had escaped. The law empowered federal marshals — officers of the United States government, not local police —to enforce it directly in Northern states where slavery had been abolished. This was unprecedented: It was the first time in American history that the national government established a local law enforcement presence.

The law also required state and local officials to actively cooperate with capturing fugitives, regardless of whether their states allowed slavery. Beyond that, it deputized ordinary citizens to participate in the hunting by granting marshals the authority to conscript passersby to act as their impromptu assistants. If someone refused to help a marshal catch a fugitive slave, they could be fined up to $1000. Those who interfered with a capture risked half a year in prison.

Meanwhile, the legal process applied to fugitive slaves was designed for conviction. Once captured, an accused fugitive would be brought before a federal commissioner — a government-appointed official, not a judge or jury — for a summary hearing. The enslaver needed only to present “satisfactory proof” of ownership, which could be as little as a sworn affidavit from a Southern court. Such affidavits were treated as conclusive evidence. The accused, however, was barred from testifying in their own defense.

And the system was financially rigged: Commissioners earned $10 for every person they returned to slavery, but only $5 if they ruled the evidence insufficient. The law didn’t just permit injustice. It paid for it.

When “undocumented” meant Black

Racial profiling was the engine of slave-catching in the 1800s, much as it is the engine of immigration enforcement today. Consider the story of Solomon Northup. A free Black man born in New York, Northup was a farmer, laborer, and talented fiddler. His father had been enslaved but was freed after his master’s death and eventually acquired enough property to vote. Solomon received an education, married, and built a life in Saratoga Springs.

That all changed when two strangers approached him in spring 1841 with what seemed like a promising opportunity: paying work as a musician in a traveling show headed toward the nation’s capital. In Washington, the con turned violent. Northup was poisoned, and when he came to, he found shackles on his wrists. Traffickers moved him through Richmond and by sea to New Orleans, where he was auctioned off into slavery under the name “Platt Hamilton.” For the next twelve years, Northup passed through several owners in Louisiana’s Red River region.

Northup wasn’t targeted by accident. He was targeted because he was Black, and in antebellum America, any Black person could be turned into property if no one was around to stop it. Northup had papers. He was a citizen. It didn’t matter then, and as we are seeing today with the normalization of racial profiling and widespread arrests of citizens by immigration officers, it does not matter now.

Historian Richard Bell even documents that a secret network of human traffickers, which he calls the “Reverse Underground Railroad,” kidnapped tens of thousands of free Black people from Northern cities and sold them into slavery in the Deep South. Any Black person could be seized on the street and, if they could not immediately produce documentation — or if that documentation was ignored or destroyed — they were fair game. Northup’s case became famous only because he managed to get word out and secure his release. Most never did.

According to a UCLA analysis, Latinos accounted for nine out of ten ICE arrests during the first six months of 2025, and arrests nearly doubled during Trump’s first 100 days in office. Community-based enforcement, meaning raids targeting people in their neighborhoods rather than at the border or in jails, surged by 255%.

In September 2025, the Supreme Court gave this surge legal cover. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, in a solo concurrence in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo, laid out a framework that would permit agents to weigh a person’s apparent ethnicity, the language they speak, and where they’re encountered as part of the calculus for a brief stop. Advocates have dubbed the resulting encounters “Kavanaugh stops,” brief detentions in which agents stop people based on how they look or sound, check their papers, and release them if they’re determined to be lawfully present in the US.

As University of Minnesota law professor Emmanuel Mauleón told the Star Tribune, the opinion represents “a major turn in the doctrine” because “it would essentially be adopting the position that racial profiling, ethnic profiling, is reasonable under the Constitution, which no other court has said thus far.” In addition, there’s no official definition of what constitutes a “brief” stop, and there have been reports of people being held for hours or even days before being released.

The Trump administration claims immigration enforcement is targeting “the worst of the worst,” but according to the Migration Policy Institute, the share of ICE detainees with criminal convictions dropped from 65% in October 2024 to just 35% by September 2025.

Most people being detained now have committed no crime at all — the status of being “undocumented” in the US is a civil violation, not a criminal one.

Boston’s resistance

Prior to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, an 1842 court ruling had absolved free states of any duty to cooperate in the recapture of escaped slaves. The 1850 law was a direct response, forcing Northern states back into complicity. In cities like Boston, though, abolitionists responded with fury and organization.

Soon after the law was passed, Frederick Douglass electrified a crowd when he took the stage at Faneuil Hall and issued a warning: If Bostonians accepted the Fugitive Slave Act, he declared, they should be “prepared to see the streets of Boston flowing with innocent blood.” He reminded them they stood on the very ground where blood “first spouted in defence of freedom.” By the meeting’s end, the Boston Vigilance Committee had been born.

The committee pledged to protect Black residents by any means necessary. They would provide shelter, legal aid, and passage to Canada. They alerted Black neighbors when bounty hunters were spotted in the area. When slave catchers did manage to apprehend people, committee members mounted bold efforts to free the captives.

One member’s resolution captured the spirit: “Constitution or no constitution, law or no law, we will not allow a fugitive slave to be taken from Massachusetts.”

The Crafts were among the first targets. They were a married couple who had escaped enslavement in Georgia by having Ellen disguise herself as a white male slaveholder, with William pretending to work for her. Abolitionists ferried them across the Atlantic before the hunters could close in. Shadrach Minkins, a formerly enslaved man who worked as a waiter at a Boston coffeehouse, was seized when federal marshals pretended to be customers. When he was taken, a group of Black Bostonians stormed the courtroom mid-hearing, pulled him from custody, and relayed him northward until he crossed into Canada.

The resistance was not always successful. For example, like Anthony Burns — whose capture inspired the mass demonstration in 1854 — Thomas Sims was captured, jailed, and ultimately sent back South despite a failed breakout attempt by abolitionists. But the spectacle of armed troops marching shackled men through Boston’s streets converted fence-sitters to the cause of abolition. As Amos Adams Lawrence recalled: “We went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs and woke up stark mad Abolitionists.”

The Fillmore administration responded by deploying soldiers to shield bounty hunters from local opposition.

Seven Northern states — from Vermont to Wisconsin — responded with “personal liberty laws.” These statutes barred state and local government employees from aiding slave catchers, closed local jails to those who sought to detain runaways, and guaranteed jury trials for anyone accused of being a fugitive. Today’s sanctuary city policies are the direct echoes of those laws.

The echoes

Then, as now, one faction of the country enlisted federal power to enforce a legal regime in such a manner that other jurisdictions found morally repulsive. Then, as now, those defending enforcement claimed their targets posed a threat to public safety, despite evidence to the contrary. Then, as now, the only “crime” most people had committed was not having the correct legal status and documents. And just as watching people get dragged back to slavery turned Boston against the Fugitive Slave Act, watching ICE tear families apart, detain children, teargas and kill people has turned public opinion against the agency, prompting the current administration to threaten sending in soldiers.

The federal enforcement apparatus is growing. As the Council on Foreign Relations details, “the One Big Beautiful Bill Act allocates nearly $170 billion for immigration enforcement over the next four years, including $45 billion to expand ICE detention capacity and roughly $30 billion to hire new agents.” ICE has signed more than 1,100 agreements deputizing state and local law enforcement to perform federal immigration functions, up from just 135 in December 2024.

But resistance is growing too. In Minneapolis and St. Paul, neighbors have organized rapid-response networks through Signal chats, tracked ICE movements block by block, blown whistles to warn families, and shown up to document arrests. These are all modern versions of tactics used by the Boston Vigilance Committee to shadow slave catchers in the 1850s. In recent weeks, tens of thousands have marched in below zero temperatures to express their dissatisfaction with the current administration’s brutal campaign, much like Bostonians who gathered to protest the seizure of their Black American neighbors.

The Fugitive Slave Act was not defeated by compliance. It was defeated by people who decided that unjust laws — and like in this modern case, overly aggressive, constitutionally dubious enforcement of those laws — deserve resistance. The abolitionists who turned Boston into a “no-go zone” for slave catchers were not acting within the bounds of the law. They were acting within the bounds of conscience.

The Burns affair became a national flashpoint, drawing widespread sympathy and sparking violent clashes in the streets. The unrest surrounding Burns’s capture pushed Massachusetts lawmakers to enact sweeping new protections in 1855, effectively shutting down fugitive slave bounty hunting within state borders with the Massachusetts Personal Liberty Act. The law barred Massachusetts officials from aiding fugitive slave proceedings, prohibited use of state and county jails for related detention, provided for jury trials in habeas corpus proceedings involving fugitive claims, and created state-supported legal protections, including access to counsel for accused fugitives.

Today, over 30 cities, counties, and states have enacted sanctuary laws with similar provisions, such as barring local police from honoring ICE detainers without judicial warrants, prohibiting use of state jails for immigration detention, and limiting information-sharing with federal authorities. California’s 2025 SB 48 went further, restricting ICE access to school campuses. The Trump administration has responded by identifying and castigating these jurisdictions, threatening to withhold federal funding and, in some cases, pursuing legal action. The Immigrant Defense Project has written extensively about these attacks and proposed reforms that these and other cities can adopt to further protect residents from ICE and the federal government.

The people who enforced the Fugitive Slave Act now occupy history’s moral dustbin. The question for all of us now is simple: Which side do you want to be remembered on?

This piece is phenomenal. It should be published far and wide. It ought to be a featured editorial piece in every major newspaper.

Thank you! This article is an entire history course, and yes, it should be published in all major printed/online newspapers and journals. I can truly say, many of us went to sleep concerned citizens and woke up resistance fighters.