How Hard Can It Be, Boys Do It?

The woman who built an army, and then was erased from its history

The sun was already high and hot over Oregon’s Willamette Valley that summer day in 1944. Florence Hall’s legs carried her purposefully down the neat rows of trees, the scent of ripening peaches wafting past. Nearby, young women filled baskets and hauled crates. Florence, now in her mid-50s, was there to check up on the program she built, which would help win the war for the Allies. “The work will be hard and long,” Florence said. “But women bring dexterity, speed, and patriotism to the job.”

Little more than a year earlier, Hall had been handed what seemed like an impossible assignment: figure out a way to make up for the million men missing from American farms. The unplanted fields and unharvested crops would be as dangerous an enemy, she was told by officials above her, as the men from foreign lands piloting planes and commandeering ships. Hall was named the chief of the Women’s Land Army, and now, a year later, she watched as college students, teachers, and clerks who had never stepped foot on a farm before the war moved through the trees like they’d been there all along.

The Women’s Land Army was born of desperation. But in the verdant Willamette Valley, the blue-skied sunshine of California, the muggy Midwest where the air felt too thick to breathe, and the briny breeze off the Atlantic was all the proof needed to silence the naysayers: the nation’s victory depended on work being done by women.

Hall knew she wasn’t just facing a shortage of workers. What she had on her hands was a shortage of belief. When she set out to recruit women, even newspapers that seemed amenable to the idea printed skeptical articles: “Can women really drive a tractor?” they seemed to ask, incredulously. “You’d have us believe that women can plow?”

But if she was to build a Women’s Land Army, Hall didn’t have time to waste on nonsense. Men looked for a fight, but Florence Hall answered with infrastructure. Within a few weeks of her appointment in April 1943, she had built a network through the USDA’s extension offices that reached nearly every county in the 48 states. Hall opened training camps, distributed pamphlets on tractor safety, and taught new recruits how to milk a cow and thin a fruit tree.

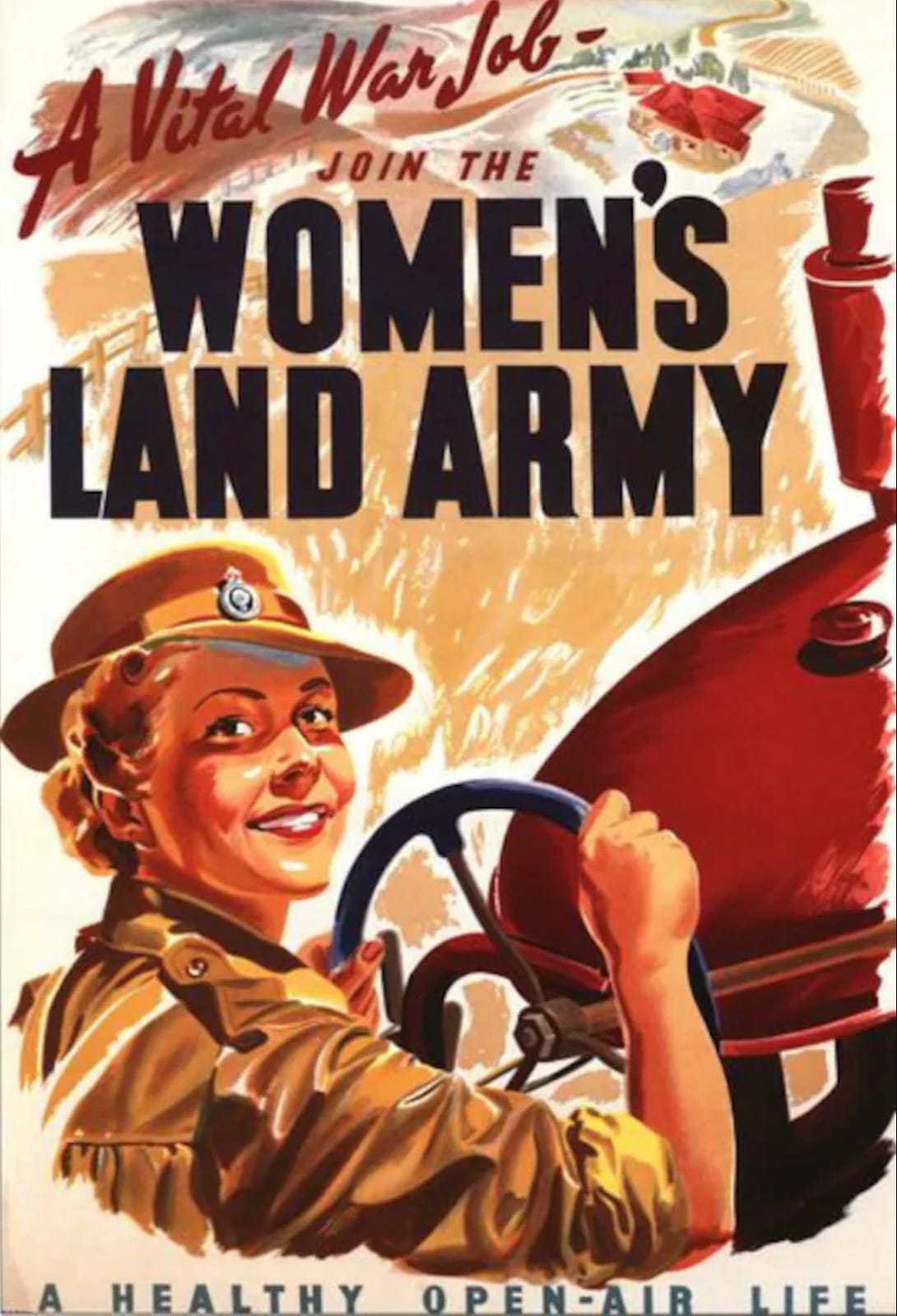

“A Vital War Job,” posters read. “Join the Women’s Land Army, a healthy open-air life.”

By fall, Hall’s program had placed nearly half a million women on farms around the country. Newspapers called the workers “farmerettes” –– it’s so important to have gendered diminutives, right? however shall we minimize the contributions of women without them? –– and many “farmerettes” were college students who were earning academic credit. Others were housewives who had never traveled farther than the next town over. They lived in musty school dormitories and on dusty fairgrounds, their days beginning before the rooster crowed and ending after crickets began their nightly symphony. Their pay averaged 40 cents an hour, and while the government sold uniforms for $6 –– denim overalls, cotton shirts, and a patch stitched over the pocket that said “WLA U.S.A.” –– many women simply wore their own perfectly serviceable work clothes. To offset the fact that many housewives were now no longer staying home, more than 3,100 federally sponsored daycares were established for young children.

The tonnage tallied, the acres planted, and the counties saved from crop loss ticked their way into Hall’s hands. With every report, the news got better. By the end of year one, the Women’s Land Army had helped yield record quantities –– sometimes more than 20% greater than the year prior –– of wheat, fruit, and vegetables, despite the absence of men. Hall’s own reports could barely contain her pride: “Without these women,” she said, “the nation’s food supply could not have been maintained.” The country could ask for difficult things, and women could do them.

In Michigan alone, more than 30,000 women with no prior farm experience had been placed in bean fields, put to work in orchards, and had their muscles taxed in dairies. Michigan State College taught animal husbandry, tractor maintenance, and safe canning techniques. In 1944 alone, more than one million women of the WLA worked a total of 13 million farm days from coast to coast.

By 1946, the war was won, the bellies of the Allies were stoked with wholesome American fuel, and the Women’s Land Army was winding down. County extension offices began returning unused uniforms and closing their training camps. The War Food Administration dissolved, its functions folded back into the USDA. Hall stayed on long enough to supervise the archiving of her files and to send one last circular to the states, thanking them for “a job well done under the most trying conditions.” Then the correspondence stopped. The final annual report was filed in 1947.

The files were packed into boxes and sent to the National Archives, labeled: “Extension Service: Women’s Land Army.” There they remained, unexamined, for decades while Rosie the Riveter took center stage. It wasn’t until the late 20th century that historians opened the boxes and found Hall’s meticulous records inside. Her handwriting covered the pages: notes about wages, yields, and which counties needed more labor still.

Those rediscovered records formed the backbone of a US National Archives’ exhibit called “To the Rescue of the Crops.” It was the first time Florence Hall’s name had appeared in a national publication in half a century. She had built one of the most successful mobilizations of women in world history, and she had done it without receiving lasting credit.

In one of the rediscovered folders, filed under “Oregon — Field Reports, 1944,” is a single black-and-white photograph of Florence Hall and two state-level WLA supervisors. Florence wears a gingham dress and a scarf tied at her neck, and she stands partially covered by a peach tree.The archivist’s description reads simply, “Miss Florence L. Hall of Washington, D.C., chief of the Women’s Land Army (left) visits the La Follette peach orchard in Marion County, Oregon.” Nothing about the millions of acres harvested under her direction. Nothing about the world saved from fascists by way of women harvesting fruit. Just a brief caption beneath an unposed image: a woman ensuring, without credit, that the work got done. Little would Hall know that 80 years in the future, more than half of farms in the US would have at least one female decision maker.

The photograph is nothing if not the perfect emblem of Florence Hall’s legacy: steady hands in the middle of a war, holding up the harvest. Waiting half a century to be seen.

Oh my! Tears! I'm so full of emotion and pride for the women! I'm 67 and have never heard about this. Rosie the Riveter, yes, but not these women. I live in farm land in central California and it makes so much sense; can't believe it never crossed my mind to wonder what happened to the farms when the men went away. Thank you for this beautiful and inspiring article!

These kind of stories, about what people achieved together during WWII are what is missing from our country’s response since 9/11 imho. Where was leadership inspiring us & harnessing our energies to work together to help our country recover & grow. Instead we focused on increasing personal wealth at the expense of our country. This is key to the moral failings we see in government today it seems to me. Curious if others share a similar view.